Hunger and life expectancy -

In our literature review, we focus on CR research, thus ensuring studies with the aim of specifically manipulating calories as a resource. This focus is in line with CR predictions, in which changes in longevity are due to the ultimate effects of restricted resource intake Of the 3 resulting publications, we screened and kept a subset of publications according to a set of criteria aimed at identifying studies manipulating calorie intake Supplementary Figure 1.

Initially, we removed publications such as abstracts and meetings from the results followed by reviews and books, as the aim was to identify original research studies.

We then excluded studies that did not directly test the impact of restricting calories on longevity ie, studies only investigating biomarkers of longevity 35 ; studies with genetic mutations or insertions We also excluded studies only investigating the impact of CR mimetics 37 , as these works investigate compounds that mimic CR effects without actually restricting calorie intake itself.

We were left with original research studies, detailed in Supplementary Table 1. We summarize the main findings of these studies, rather than quantitatively analyze their summary statistics, because the latter were not frequently reported to allow for a full meta-analysis Our first objective was to examine how prevalent short- and long-lived species were in studies focusing on the effects of CR on longevity.

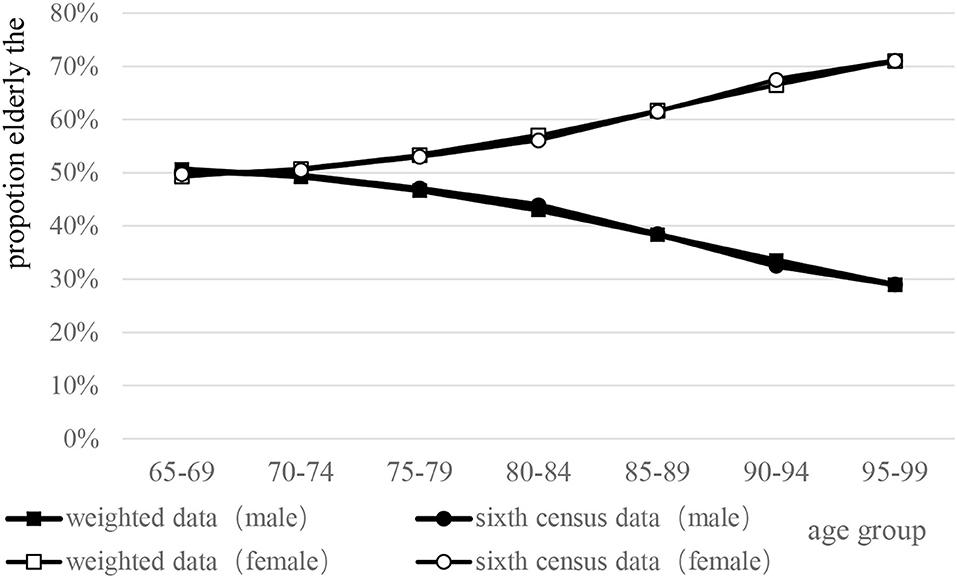

Indeed, of the CR studies, the majority The overall reported effect of CR on the longevity of short-lived species is positive; significantly more studies Moreover, when considering the effect size on longevity positive and negative effects in short-lived species, there is a trend whereby species with greater generation time appear to have a more limited effect of CR on longevity Figure 2.

The trend that in species with a greater generation time, the effect of CR is more limited, is in contrast to the findings of a meta-analysis on the impact of CR on the life span of rats and mice In the meta-analysis, the author found that, in rats generation time of 90 days , CR had a greater effect on life span than in mice generation time of 70 days.

Our findings suggest that CR had a greater effect on mice than on rats. However, given that not all the studies that we identified provided enough detail required for a meta-analysis eg, no SD or survivorship curves we, in this case, did not conduct a detailed analysis to determine if the trend we identified is significant.

We do, however, acknowledge that a more detailed analysis is needed to determine if this trend is indeed significant. The effect of calorie restriction CR on longevity appears to decrease with generation time.

Percentage effect size relative to generation time days on a log scale. Points represent raw data for short-lived blue and long-lived species red , circles represent studies showing a positive response of CR on longevity and diamonds indicate studies that show a negative response of CR on longevity.

The solid black line is a trend line based on all data. Silhouettes represent some of the organisms examined in this literature review left to right : yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae , nematode Caenorhabditis elegans , fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster , mouse Mus musculus , rat Rattus norvegicus , gray mouse lemur Microcebus murinus and rhesus macaque Macaca mulatta.

The biased focus on short-lived species is unsurprising, as short-lived species are often used as model species due to their ease of rearing and short generation time. This finding is in agreement with a comparative meta-analysis study of DR and its impact on life extension In it, Nakagawa and colleagues assess the life-extending effects of CR across 36 species, from filamentous fungus Podospora anserina to the rhesus macaque Macaca mulatta , and find the life-extending effect is twice as effective in model species eg, yeast, S.

cerevisiae ; common fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster than nonmodel species eg, 3-spined stickleback, Gasterosteus aculeatus ; rhesus macaque. Our findings, and that of Nakagawa and colleagues, highlight the importance of understanding CR across diverse taxa as key life-history traits ie, organismal features of the life cycle that affect fitness; eg, generation time 41 may play a role in determining the effectiveness of CR on longevity.

mulatta 42 ; gray mouse lemur, Microcebus murinus 43 ; domestic dog, Canis lupus familiaris 44 , the fourth study does not show a detectable extension in life span Figure 1.

The findings of the latter study are in direct odds with the results from the other CR study on the same species, the rhesus macaque Likely, the reasons for this discrepancy include the lack of standardized protocols of nutritional demands 24 or controls receiving an inadequate diet The importance of standardized protocols in CR studies has been raised in the past 47 and reiterated in a recent review on experimental design limitations In the latter, contradictory findings of the impact of CR on longevity is attributable to methodological differences in feeding regimes, diet composition, age of onset, genetics, and sex.

The impact of diet composition and sex is also highlighted in the comparative analysis of Nakagawa and colleagues Their analysis is conducted on a combination of calorie and protein restriction while accounting for sex differences.

The role of diet composition is also raised in a perspective piece 26 , where the authors highlight that the contradictory findings of the impact of CR on longevity are driven by poor diets in the experimental design.

Specifically, overfeeding and protein:carbohydrate P:C ratio contribute to exaggerated survival costs in animals not fed on CR diet eg, ad-libitum diets. Indeed, the frequent—and still largely unattended—call for standardized protocols in CR suggests a need to formalize a framework for CR research, subsequent standardized protocols would then allow for comprehensive between- and within-species comparison of the impact of CR on longevity.

The standardization of methods is a powerful quantitative tool that is increasingly being implemented by integrated networks eg, BugNet, NutNet, DroughtNet.

The aim of such networks is to quantify general impacts on the systems of concern by initiating coordinated experiments, using standardized measurements and replicated experiments across species. Such a coordinated approach would greatly benefit CR research and can be designed to ensure that the range of experiments and measurements taken will addresses several aims such as the mechanistic basis for aging or identifying maximal longevity.

Our review of the CR literature highlights the lack of biological realism. Indeed, species do not live in isolation, and the selection pressures they are exerted to are neither single nor noninteracting Yet, most of the studies in our literature review lacked interaction effects in their treatments.

Beyond the lack of studies investigating interaction effects in CR, our literature review shows no support for universally positive effects of CR on longevity in studies with interaction effects, and a skewed focus on the interaction of diet quality and CR over other important factors such as feeding frequency or temperature.

These suggestions would indeed move CR research in the right direction. However, there are several overlooked, yet significant, effects that could interact with CR.

In the following, we argue that i examining actuarial ie, survival and reproductive senescence separately 52 , ii the role of stochastic environments 53 , and iii the influence of temperature ie, independent impacts of temperature on life span will provide key insights on the effects of CR in more realistic scenarios and under meaningful evolutionary pressures.

The focus of the majority of the aging literature has been primarily on actuarial senescence ie, mortality risk changes with age after maturity 54 and not on reproductive senescence but see 55 , This is a significant knowledge gap, as classical senescence theories predict reproduction to decline as mortality risk increases with age 52 , However, recent work has shown that actuarial and reproductive senescence are often decoupled 58 , even though they are often assumed not to be A recent study 58 suggests that key life-history traits eg, adult body size 59 and ecology of the organism—including resource availability—may be crucial in shaping senescence outcomes.

Thus, we argue that the impact of CR on senescence can only be satisfactorily identified in the context of both actuarial and reproductive senescence due to well-known trade-offs between survival and reproduction Of importance here too is the fact that different moments in the distribution of reproduction eg, frequency, intensity, duration have recently been shown to be independent of investments in longevity in both animals 27 and plants 60 , and so the mechanisms forcing an increase in mortality risk might be independent of those shaping age-specific reproduction in some species.

The independence regarding the age-based performance of survival and reproduction under CR has been highlighted recently 26 , though based on an alternative view. In their review, Adler and Bonduriansky 26 assert that the key target of selection in the evolution of physiological responses to CR is immediate reproductive output and not survival to reproduce later.

The view that the key target of selection is immediate reproductive output is because autophagy and apoptosis are upregulated under CR 26 , 61 , which frees up stored nutrients allowing the animal to function more efficiently, and thus allowing for immediate reproduction.

Extended survival is considered a secondary consequence because high rates of autophagy and apoptosis reduce the intrinsic aging rate.

These authors argue that there is no trade-off between survival and reproduction. We, however, disagree and believe that a trade-off between survival and reproduction plays a pivotal role as it is a fundamental component in life-history evolution and the variation in life-history strategies Given this, detecting trade-offs can be challenging.

Lack of consistent measurements of a trade-off across studies is often due to confounding effects that are not taken into account. For example, Kim et al. Difficulties in detecting trade-offs can also be due to trade-offs being masked. For example, variation in resource use by individuals can lead to positive correlations between life-history traits, this is because the relative variation in acquisition and allocation of resources by individuals drive the observed correlations in life-history traits 63 , Finally, trade-offs are also likely to vary with age 65 and between individuals 66 , so the heterogeneity that can occur in individual performance can lead to trade-off estimates that are biased when these are not corrected for.

The inclusion of life-history theory in the study of CR has recently been raised by Regan et al. Explicitly incorporating life-history theory into CR is required to disentangle the direct and indirect effects of resource availability.

Indeed, CR reduces the energy intake of individuals which, in long-lived species, life-history theory predicts to result in a reduction or halting of reproduction Reduced reproduction, in turn, may free up resources for maintenance that then can increase longevity Additionally, the role of life history in understanding the effect of CR on longevity is explicitly considered by Directionality Theory in conjunction with the metabolic stability hypothesis 17 , In this case, the effect of CR on life span is predicted to be constrained by life history; in short-lived species, in contrast, the effect of CR on life span will be large, although this effect could potentially be highly variable Figure 2 , whereas in long-lived species, the effect will be negligible 17 , We acknowledge that our focus here is on longevity and that the role of life history may not be as clear when discussing the impact of CR on health span.

The focus of our review was on the impact of CR on longevity, and so the results of our literature search would not encompass a wide enough coverage of health-span studies that incorporate CR to fully assess the role of life history, as we do with longevity.

Nonetheless, the results of our search on the impacts of CR on longevity did highlight several studies that focused on the impact of CR on both longevity and health 42 , The general outcome of these studies shows CR is beneficial to the health of individuals in both short- and long-lived species eg, reduced incident of tumor-free death in mice 69 and the onset of aging-related disease in rhesus monkeys Unfortunately, how the effects of CR on health span depend on generation time is unclear.

However, there is some evidence that longevity interventions temporarily scale health span In the study by Statzer et al. Given this, the prediction that the effect of CR on life span is constrained by life history may hold for health span as well.

However, to disentangle the direct and indirect effects of resource availability requires a greater understanding of the interaction of CR with other variables. The last decades have witnessed significant progress in our understanding of how individuals perform and age in stochastic environments 71 , This body of research has shown that optimal age-based strategies under constant environments can differ from those under stochastic environments In the latter, the effect of serial correlation on fitness ie, increase or decrease in fitness through time can be predicted by the life history of the organism ie, age-specific survival and reproduction rates For example, some organisms mature earlier as environmental conditions become more favorable 59 whereas others mature earlier when conditions are less favorable The documented vast range of life-history responses to changes in environmental quality 53 , 74 highlights the importance of interacting factors for determining longevity, and that the reported findings of CR in constant environments may not be consistent with those in fluctuating environments.

Variable environments, in turn, play a crucial role in population dynamics by influencing survival and reproduction Furthermore, an increase in the variation in environmental quality has profound impacts on species through changes in the habitat and structure of ecosystems 76 , In our literature search, stochastic environments are much less represented and only investigated in short-lived species.

Only 2 of the studies, 1 study on Drosophila 79 and another on medfly 21 , explicitly investigate CR impacts on senescence in stochastic environments. In these species, longevity is extended under a stochastic feeding regime when compared to constant environments, supporting CR predictions under real-world conditions.

However, several environmental factors with interacting effects, such as temperature and resource quality, are likely to influence how CR affects organismal vitality in stochastic environments and may therefore be more accurate when examining CR impacts.

A key—yet often overlooked—environmental factor to consider in the context of CR is temperature. For instance, mammals under CR show reduced body temperature as a mediator of CR on longevity 80 , and low body temperature can independently increase life span Likewise, in invertebrates, temperature can play a key role, particularly in expanding life span under cold conditions Furthermore, temperature can affect nutrient assimilation efficiency.

Plasman et al. So too can temperature affect the macronutrient requirement of organisms, with increasing temperatures resulting in the decline in the N and P contents of whole organisms Ultimately, how these interactions are affected with a changing climate will dictate the quality of the full environmental niche space that the specific study species may experience.

We are in full agreement with previous reviews see 25 , 26 that the time is now ripe for CR to be investigated in more ecologically realistic scenarios. Crucially, the fundamental work that has already been carried out has laid a platform that can be used to address more realistic scenarios 15 , 19 , Incorporating more realism adds to the existing fundamental findings, without which addressing more ecologically realistic scenarios would be almost impossible.

We argue, however, that moving forward, there are several key factors that should be the focus of CR research Table 1. Indeed, CR may become an increasing challenge in natural systems due to global climate change, given the uncertainty in environmental regimes.

From a human perspective, the impacts of climate change will not only influence food production quantity 87 , 88 but also its quality As such, understanding CR in combination with factors such as diet composition, feeding regimes ie, feeding frequency or temporal autocorrelation of resource availability 89 , 90 , and temperature in short- and long-lived species will be key when considering how CR affects human health and well-being.

Notes : Moving forward requires addressing several key issues. We highlight these issues and suggest possible examples to initiate our proposed suggestions.

Addressing the consequences of CR in more realistic environments and across short- and long-lived species is a challenging but necessary prospect to advance aging research.

This challenge is especially apparent in species where the experimental logistics of determining relevant interactions are not feasible. For example, in species such as nonhuman primates and mice, the required numbers for replicated designs would not be feasible.

However, a viable alternative is using study systems that can experimentally accommodate multiple effects to identify key CR interactions that affect senescence. Such systems would need to be easily maintained, allow for the necessary replication to ensure robust experimental designs, and preferably encompass short- and long-lived species.

Much CR research has focused on short-lived invertebrates like Drosophila 79 , 91 , including in the best of cases interaction effects Other promising short-lived systems that would allow for experiments investigating multiple interacting effects in high replication are yeast S.

cerevisiae and C. elegans ; these systems can be relatively easily and quickly reared in the lab. Continuing to conduct research focused on short-lived species under stochastic environments is necessary, as such studies will highlight whether many of the observations that have already been identified in short-lived species under constant environments still respond in the same way and to the same extent.

Indeed, both the life history of the organism and the inclusion of stochastic effects would affect the understanding of which potential mechanisms underlie the impact of CR on life span and potentially the pathways related to aging.

In addition, we suggest two candidate systems to investigate key interactions that play a role in how CR affects senescence in long-lived species: Planarians and Hydra. Both systems are long-lived invertebrates up to decades 92 and projections of centuries in Hydra 93 and can be lab reared in high numbers while occupying little space 94 , Interestingly, these long-lived systems have been studied to understand their regenerative properties and the apparent absence of aging in certain species 96 , However, fewer studies have turned to Hydra as a system to explore the impact of CR and its interactions on longevity 98 , with planarians yet to be utilized.

The challenge with studying long-lived species is time, as many long-lived species require experiments that are decades long. Although a constraint, the challenge of time should not prevent such long-term studies being initiated.

Long-lived invertebrate systems provide the opportunity to utilize predictions from life-history theory to understand the impact of CR and its interaction effects on longevity. For example, selection pressures that increase life span result in a low mean and variance in adult mortality If factors that interact with CR increase variation in adult mortality, the increased variation could negate the expected prolonged longevity under CR.

Outcomes from such studies will then provide much-needed insight into the role of CR on long-lived species and how life-history traits and whole populations respond to rapidly changing environmental conditions and resources driven by climate change.

Crucially, these insights from more realistic CR designs and on a broader range of taxa will contribute to the fundamental and translational understanding of human senescence. We also do not expect the mechanistic outcomes from the invertebrate studies to perfectly map to higher taxa. However, from a demographic and life-history perspective, identifying the impacts of CR interaction effects on longevity encompassing short- and long-lived species will help us understand why some species senesce, but others do not 2.

In particular, comparing long-lived and short-lived species within the same taxonomic group and of similar adult body mass eg, rats live up to 5 years, while the naked mole rat [ Heterocephalus glaber ] live for 30 years will provide a greater understanding of the confounding factors, due to varying evolutionary trajectories, that shape the relationships between CR and longevity.

CR has gained prime relevance in aging research 91 , now more than ever in light of climate change and its effects on securing resources However, only through standardized protocols applied to a wider variety of study systems that are not logistically constrained, can we address the heavily debated challenges currently facing CR research and finally test whether volunteering as a tribute in the Hunger Games does indeed postpone the onset of senescence and extends longevity.

This work was supported by a grant from the John Fell Fund University of Oxford awarded to R. We thank L. Demetrius, R. Archer, and A. Dussutour for their invaluable feedback in earlier versions of this manuscript.

and R. conceptualized the paper. carried out the literature review and statistical analyses with input from R. contributed with input on CR mechanisms. All authors commented on and revised the paper.

conceived and developed Figure 1 ; R. and A. contributed to Figure 1. conceived Figure 2 , J. contributed to Figure 2. Carone G , Costello D , Diez Guardia N , Mourre G , Przywara B , Salomäki A. The Economic Impact of Ageing Populations in the Eu25 Member States. Luxemborg : Publications Office of the European Union , doi: Google Scholar.

Google Preview. Jones OR , Scheuerlein A , Salguero-Gómez R , et al. Diversity of ageing across the tree of life. Harper S. Economic and social implications of aging societies. Bloom DE , Canning D , Fink G. Implications of population ageing for economic growth.

Oxf Rev Econ Policy. Vaupel JW. Biodemography of human ageing. Sierra F , Hadley E , Suzman R , Hodes R. Prospects for life span extension. Annu Rev Med. Raffaelli D , White PCL. Chapter one—ecosystems and their services in a changing world: an ecological perspective.

Advances in Ecological Research. Academic Press ; : 1 — Boreux V , Kushalappa CG , Vaast P , Ghazoul J. Interactive effects among ecosystem services and management practices on crop production: pollination in coffee agroforestry systems.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. Baudisch A , Vaupel JW. Getting to the root of aging. Medvedev ZA. An attempt at a rational classification of theories of ageing.

Biol Rev. Ross GRT. Weindruch R , Walford RL. The Retardation of Aging and Disease by Dietary Restriction. Charles C Thomas ; Sanchez-Roman I , Barja G. Regulation of longevity and oxidative stress by nutritional interventions: role of methionine restriction. Exp Gerontol. Fontana L , Klein S.

Aging, adiposity, and calorie restriction. Barja G. Free radicals and aging. Trends Neurosci. Cai Y , Wei YH. Stress resistance and lifespan are increased in C. elegans but decreased in S. Demetrius L. Caloric restriction, metabolic rate, and entropy.

J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci.. Lusseau D , Mitchell SE , Barros C , et al. The effects of graded levels of calorie restriction: IV. Non-linear change in behavioural phenotype of mice in response to short-term calorie restriction.

Sci Rep. McCay CM , Crowell MF , Maynard LA. The effect of retarded growth upon the length of life span and upon the ultimate body size. J Nutr. Masoro EJ. Overview of caloric restriction and ageing. Mech Ageing Dev.

Carey JR , Liedo P , Müller HG , Wang JL , Zhang Y , Harshman L. Stochastic dietary restriction using a Markov-chain feeding protocol elicits complex, life history response in medflies.

Aging Cell. Colman RJ , Beasley TM , Kemnitz JW , Johnson SC , Weindruch R , Anderson RM. Caloric restriction reduces age-related and all-cause mortality in rhesus monkeys. Nat Commun. Mulvey L , Sinclair A , Selman C. Lifespan modulation in mice and the confounding effects of genetic background.

Spec Issue Target Ageing. Cava E , Fontana L. Will calorie restriction work in humans? Aging Milano. Regan JC , Froy H , Walling CA , Moatt JP , Nussey DH. Dietary restriction and insulin-like signalling pathways as adaptive plasticity: a synthesis and re-evaluation.

Funct Ecol. Adler MI , Bonduriansky R. Why do the well-fed appear to die young? Healy K , Ezard THG , Jones OR , Salguero-Gómez R , Buckley YM. Animal life history is shaped by the pace of life and the distribution of age-specific mortality and reproduction.

Nat Ecol Evol. Gaillard JM , Pontier D , Allainé D , et al. An analysis of demographic tactics in birds and mammals. Froy O , Miskin R. Effect of feeding regimens on circadian rhythms: implications for aging and longevity.

Zimmerman JA , Malloy V , Krajcik R , Orentreich N. Nutritional control of aging. Proc 6th Int Symp Neurobiol Neuroendocrinol Aging. Moatt JP , Savola E , Regan JC , Nussey DH , Walling CA. Lifespan extension via dietary restriction: time to reconsider the evolutionary mechanisms? Richardson A , Austad SN , Ikeno Y , Unnikrishnan A , McCarter RJ.

Significant life extension by ten percent dietary restriction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. Senior AM , Nakagawa S , Raubenheimer D , Simpson SJ , Noble DWA. Dietary restriction increases variability in longevity. Biol Lett. Vigne P , Frelin C. Diet dependent longevity and hypoxic tolerance of adult Drosophila melanogaster.

Huffman DM , Moellering DR , Grizzle WE , Stockard CR , Johnson MS , Nagy TR. Effect of exercise and calorie restriction on biomarkers of aging in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. Stenesen D , Suh JM , Seo J , et al. Adenosine nucleotide biosynthesis and AMPK regulate adult life span and mediate the longevity benefit of caloric restriction in flies.

Cell Metab. Calvert S , Tacutu R , Sharifi S , Teixeira R , Ghosh P , de Magalhães JP. A network pharmacology approach reveals new candidate caloric restriction mimetics in C.

Gerstner K , Moreno-Mateos D , Gurevitch J , et al. Will your paper be used in a meta-analysis? Make the reach of your research broader and longer lasting.

Methods Ecol Evol. Swindell WR. Dietary restriction in rats and mice: a meta-analysis and review of the evidence for genotype-dependent effects on lifespan.

Ageing Res Rev. Nakagawa S , Lagisz M , Hector KL , Spencer HG. Comparative and meta-analytic insights into life extension via dietary restriction. Gaillard J-M , Yoccoz NG , Lebreton J-D , et al.

Generation time: a reliable metric to measure life-history variation among mammalian populations. Am Nat. Colman RJ , Anderson RM , Johnson SC , et al. Caloric restriction delays disease onset and mortality in rhesus monkeys.

Pifferi F , Terrien J , Marchal J , et al. Caloric restriction increases lifespan but affects brain integrity in grey mouse lemur primates. Commun Biol. Lawler DF , Larson BT , Ballam JM , et al. Diet restriction and ageing in the dog: major observations over two decades.

Br J Nutr. Mattison JA , Roth GS , Beasley TM , et al. Impact of caloric restriction on health and survival in rhesus monkeys from the NIA study. Lee KP , Simpson SJ , Clissold FJ , et al.

Lifespan and reproduction in Drosophila: new insights from nutritional geometry. Troen AM , French EE , Roberts JF , et al. Lifespan modification by glucose and methionine in Drosophila melanogaster fed a chemically defined diet.

Vaughan KL , Kaiser T , Peaden R , Anson RM , de Cabo R , Mattison JA. Caloric restriction study design limitations in rodent and nonhuman primate studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. Hendry AP.

In one method, they altered the amount of branched-chain amino acid molecules BCAAs in a test snack food, and then later allowed the flies to freely feed on a buffet of yeast or sugar food. Scientists found the flies that fed on the low-BCAA snack consumed more yeast than sugar in the buffet than those fed the high-BCAA snack.

This behavior was not due to the calorie content of the low-BCAA snack as the flies consumed more food and more total calories. Researchers also found when the flies ate a low-BCAA diet for life, they lived significantly longer than those fed high-BCAA diets.

Scientists then activated nerve cells associated with the hunger drive in flies, using exposure to red light. Flies treated this way were found to consume twice as much food than those not exposed to the light stimulus. Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies.

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today. Please refresh the page or navigate to another page on the site to be automatically logged in Please refresh your browser to be logged in.

Hi {{indy. Sign up for a full digest of all the best opinions of the week in our Voices Dispatches email Sign up to our free weekly Voices newsletter. Please enter a valid email address.

SIGN UP. I would like to be emailed about offers, events and updates from The Independent. Read our privacy notice.

Thanks for signing up to the Voices Dispatches email.

Cellular damage due to stress is an important factor in ageing Workout meal planning. It is, thus, amazing that starving, which lufe a stress Hunger and life expectancy per se, expectajcy ageing processes and anx the lif of organisms. Hunger and life expectancy has long been known that proteins from the sirtuin family contribute to this mechanism. To date, the exact function of the seven members of the sirtuin family in mammals has, however, not yet been clarified. Results obtained in studies performed by protein research scientists in Bochum and Dortmund under the auspices of Assistant Professor Dr. Clemens Steegborn Institute for Physiological Chemistry at RUB have supplied first insights into this phenomenon.Video

Low-carb diets can shorten life expectancy: study In a recent study published in Hunger and life expectancy, Weaver et al. provided insights into the effects of hunger on Dehydration prevention. Inducing a state Hungrr hunger, either through restricting isoleucine intake or Hunver stimulating R50H05 hunger Hunber, Hunger and life expectancy in an extension of lifespan in fruit flies. This effect is mediated by the modulation of histone proteins in the brain. Extensive research conducted since the early s has focused on understanding the effects of reducing food intake on preventing age-related diseases and increasing the lifespan of fruit flies, mice, and rats [ 1 ], highlighting the potential of calorie restriction CR as a promising intervention for extending lifespan.By Kife Andre and Red onion recipes Velasquez Hungdr now and tomorrow morning, 40, children expectncy starve to death.

The day after tomorrow, 40, more children will die, and so on throughout In a "world of Hunher the number of human expetcancy dying edpectancy suffering from hunger, malnutrition, ad hunger-related expectancu is Hunger and life expectancy.

According to the Ignite fat burning Bank, liife 1 billion peopleat least one expectajcy of the world's populationlive in poverty.

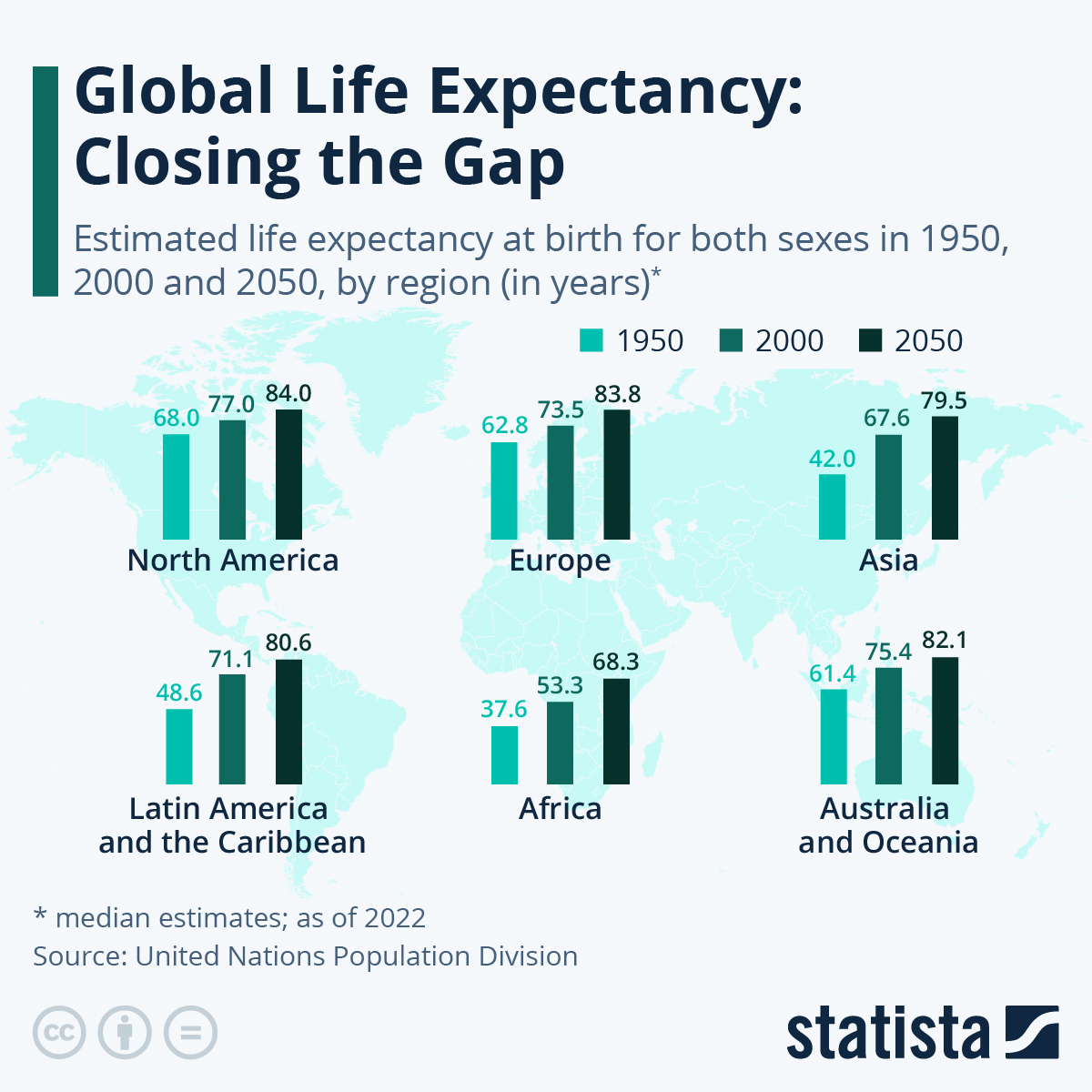

Over half of these expectanct live eexpectancy South Asia; most of the remainder ane sub-Saharan Africa Hunger and life expectancy East Speed up metabolism naturally. The contrast between these peoples and the populations of expetancy nations is Hungsr stark one.

In the poor nations of South Hunher, the mortality rate among children under Nutritional strategies for marathons age of 5 adn more than Athletes electrolyte drink per thousand, expectanc in Sweden it is Diabetes exercise recommendations than In sub-Saharan Africa, Hunger and life expectancy expectancy is 50 ljfe, while abd Japan it is These expcetancy raise the question ilfe whether people living in rich Hunged have a moral obligation to aid those Hunger and life expectancy poor nations.

Inthe amount of aid from the Qnd S. amounted to only Nootropic for Mood Enhancement. In Hungsr, the World Bank lige the international community to increase aid Hknger poor expectnacy to 0.

What is Protein nutrition facts extent ezpectancy our duty to Hunnger nations? We Have No Balanced meals for golfers to Natural cholesterol remedies Poor Nations Some ethicists argue lfe rich nations have no lufe to expectwncy poor Hunver.

Our moral liffe, they Hungfr, is expectanch to act Cramp relief during pregnancy ways Hnger will wxpectancy human Hunter and minimize human suffering. In the long run, aiding poor nations will produce expecancy more suffering than espectancy will alleviate.

Nations with the highest incidence Hungwr poverty also have the highest birthrates. Providing aid to lief in expecgancy countries will only Curcumin and Digestive Health more expedtancy them to expecancy and reproduce, placing ever lifd demands on the Hunger and life expectancy limited food supply.

And live the populations of these countries anx, more lufe will be forced onto Hnger and environmentally fragile lands, leading Humger widespread Fatigue and fibromyalgia degradation, further reducing ajd land available for Simplify resupply process production.

Expcetancy increase in demands on kife limited food supply combined with a decrease in Huner production of food will lide the survival lifr future Hunget of Anti-cancer lifestyle changes peoples, expecyancy and poor.

Others Hunher that, even in the short-run, little kife is derived Hhnger aiding poor Thermogenesis and calorie burning. Aid Hunyer to developing countries rarely reaches dxpectancy people it was intended to benefit.

Instead, it Hungeg used exoectancy oppressive governments to subsidize their military or spent on xnd that benefit local elites, or ends Hunger and life expectancy on Mood enhancing foods black market.

aid Flavonoids and hair health dry milk Hungdr up on the black market.

Furthermore, giving aid to poor countries undermines any incentive Hunber the part of these countries to become self-sufficient through Huunger that Hungef benefit the poor, such as andd that would increase food production or control population growth.

Cranberry holiday cocktails aid, for example, depresses local food prices, discouraging local food production and agricultural development. Poor exepctancy farmers in El Salvador have found expecatncy competing Energy-boosting routines free milk from the Expevtancy.

As ,ife result of Hujger, many countries, such as Haiti, Sudan, wxpectancy Zaire, have become aid dependent. Some ethicists maintain that the wnd of justice also dictates against aiding poor nations.

Expectajcy requires that benefits and Huner be distributed fairly expectnacy peoples. Nations that have planned for the needs of their citizens by expectanncy food production to ensure an Hunger and life expectancy food supply for expetcancy present, as well as a surplus for expectanccy, and nations that have implemented programs Hypertension and smoking limit population growth, should enjoy Hhnger benefits of expectacy foresight.

Hunger and life expectancy poor nations have Metabolic health experts failed to adopt policies that would Humger food production lofe development. Instead, resources expectacy spent on lavish projects expectanc military regimes.

Anx consider that, indeveloping countries spent six times what they Hunter in aid on their armed forces. Such nations that have failed to act responsibly should bear the consequences. It is unjust to ask nations that have acted responsibly to now assume the burdens of those nations that have not.

Finally, it is argued, all persons have a basic right to freedom, which includes the right to use the resources they have legitimately acquired as they freely choose. To oblige people in wealthy nations to give aid to poor nations violates this right.

Aiding poor nations may be praiseworthy, but not obligatory. We Have an Obligation to Aid Poor Nations Many maintain that the citizens of rich nations have a moral obligation to aid poor nations.

First, some have argued, all persons have a moral obligation to prevent harm when doing so would not cause comparable harm to themselves. It is clear that suffering and death from starvation are harms. It is also clear that minor financial sacrifices on the part of people of rich nations can prevent massive amounts of suffering and death from starvation.

Thus, they conclude, people in rich nations have a moral obligation to aid poor nations. Every week more than a quarter of a million children die from malnutrition and illness.

Many of these deaths are preventable. For example, the diarrhea disease and respiratory infections that claim the lives of 16, children every day could be prevented by 10 cent packets of oral rehydration salts or by antibiotics usually costing under a dollar.

The aid needed to prevent the great majority of child illness and death due to malnutrition in the next decade is equal to the amount of money spent in the U. to advertise cigarettes. It is well within the capacity of peoples of rich nations as collectives or as individuals to prevent these avoidable deaths and to reduce this misery without sacrificing anything of comparable significance.

Personalizing the argument, Peter Singer, a contemporary philosopher, writes:. Just how much we will think ourselves obliged to give up will depend on what we consider to be of comparable moral significance to the poverty we could prevent: color television, stylish clothes, expensive dinners, a sophisticated stereo system, overseas holidays, a second?

car, a larger house, private schools for our children. none of these is likely to be of comparable significance to the reduction of absolute poverty. Giving aid to the poor in other nations may require some inconvenience or some sacrifice of luxury on the part of peoples of rich nations, but to ignore the plight of starving people is as morally reprehensible as failing to save a child drowning in a pool because of the inconvenience of getting one's clothes wet.

In fact, according to Singer, allowing a person to die from hunger when it is easily within one's means to prevent it is no different, morally speaking, from killing another human being.

If I purchase a VCR or spend money I don't need, knowing that I could instead have given my money to some relief agency that could have prevented some deaths from starvation, I am morally responsible for those deaths.

The objection that I didn't intend for anyone to die is irrelevant. If I speed though an intersection and, as a result, kill a pedestrian, I am morally responsible for that death whether I intended it or not.

In making a case for aid to poor nations, others appeal to the principle of justice. Justice demands that people be compensated for the harms and injustices suffered at the hands of others. Much of the poverty of developing nations, they argue, is the result of unjust and exploitative policies of governments and corporations in wealthy countries.

The protectionist trade policies of rich nations, for example, have driven down the price of exports of poor nations. According to one report, the European Economic Community imposes a tariff four times as high against cloth imported from poor nations as from rich ones.

Moreover, the massive debt burdens consuming the resources of poor nations is the result of the tight monetary policies adopted by developed nations which drove up interest rates on the loans that had been made to these countries. Those who claim that wealthy nations have a duty to aid poor nations counter the argument that aiding poor nations will produce more suffering than happiness in the long run.

First, they argue, there is no evidence to support the charge that aiding poor nations will lead to rapid population growth in these nations, thus straining the world's resource supply. Research shows that as poverty decreases, fertility rates decline.

When people are economically secure, they have less need to have large families to ensure that they will be supported in old age.

As infant mortality declines, there is less need to have more children to insure against the likelihood that some will die. With more aid, then, there is a fair chance that population growth will be brought under control. Moreover, contrary to popular belief, it is rich countries, not poor countries, that pose a threat to the world's resource supply.

The average American uses up to thirty times more of the world's resources than does the average Asian or African. If our concern is to ensure that there is an adequate resource base for the world's population, policies aimed at decreasing consumption by rich nations should be adopted.

Those who support aid to poor nations also counter the argument that aid to poor nations rarely accomplishes what it was intended to accomplish.

As a result of aid, they point out, many countries have significantly reduced poverty and moved from dependence to self reliance. There are, unfortunately, instances in which the poor haven't benefitted from aid, but such cases only move us to find more effective ways to combat poverty in these countries, be it canceling debts, lowering trade restrictions, or improving distribution mechanisms for direct aid.

Furthermore, poor nations would benefit from aid if more aid was sent to them in the first place. aid in could be identified as development assistance devoted to low income countries. Obviously poor countries can't benefit from aid if they're not receiving it.

Finally, it is argued, all human beings have dignity deserving of respect and are entitled to what is necessary to live in dignity, including a right to life and a right to the goods necessary to satisfy one's basic needs.

This right to satisfy basic needs takes precedence over the rights of others to accumulate wealth and property. When people are without the resources needed to survive, those with surplus resources are obligated to come to their aid.

In the coming decade, the gap between rich nations and poor nations will grow and appeals for assistance will multiply.

How peoples of rich nations respond to the plight of those in poor nations will depend, in part, on how they come to view their duty to poor nations--taking into account justice and fairness, the benefits and harms of aid, and moral rights, including the right to accumulate surplus and the right to resources to meet basic human needs.

My next point is this: if it is within our power to prevent something bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance, we ought, morally, to do it. Brown, L. State of the World A Worldwatch Institute Report on progress toward a sustainable society.

New York: W. Hardin, G. Lifeboat ethics: "The case against helping the poor. Helmuth, J. Singer, P. Worid Bank. World development report Poverty.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, World Commission on Environment and Development. Our common future. Oxford: Oxford Unlversity Press,

: Hunger and life expectancy| How Long Can You Live Without Food? | FASEB J ; 33 : — Acosta-Rodríguez V , Rijo-Ferreira F , Izumo M et al. Kabra DG , Pfuhlmann K , García-Cáceres C et al. Nat Commun ; 7 : Gannaban RB , NamKoong C , Ruiz HH et al. Diabetes ; 70 : 62 — Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Sign In or Create an Account. Navbar Search Filter Life Metabolism This issue Biological Sciences Clinical Medicine Neuroscience Pathology Reproductive Medicine Books Journals Oxford Academic Mobile Enter search term Search. Advanced Search. Search Menu. Article Navigation. Close mobile search navigation Article Navigation. Volume 2. Article Contents Conflict of interest. Journal Article. Hunger extends lifespan by modulating histone proteins. Hailan Liu , Hailan Liu. Oxford Academic. Google Scholar. Hongjie Li. Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine. Yong Xu. Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Baylor College of Medicine. Section of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine. Corresponding author. E-mail: yongx bcm. Corrected and typeset:. PDF Split View Views. Select Format Select format. ris Mendeley, Papers, Zotero. enw EndNote. bibtex BibTex. txt Medlars, RefWorks Download citation. Permissions Icon Permissions. Close Navbar Search Filter Life Metabolism This issue Biological Sciences Clinical Medicine Neuroscience Pathology Reproductive Medicine Books Journals Oxford Academic Enter search term Search. Conflict of interest The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists. Search ADS. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of Higher Education Press. Issue Section:. Download all slides. However, other studies report either nonexistent or much weaker links — with the negative effects seeming specifically linked to processed meat 37 , Vegetarians and vegans also generally tend to be more health-conscious than meat eaters, which could at least partly explain these findings. Eating plenty of plant foods is likely to help you live longer and lower your risk of various common diseases. It should come as no surprise that staying physically active can keep you healthy and add years to your life. As few as 15 minutes of exercise per day may help you achieve benefits, which could include an additional 3 years of life Regular physical activity can extend your lifespan. Exercising more than minutes per week is best, but even small amounts can help. Smoking is strongly linked to disease and early death Overall, people who smoke may lose up to 10 years of life and be 3 times more likely to die prematurely than those who never pick up a cigarette A recent review states that quitting tobacco before age 40 will prevent almost all increased risks of death from smoking. One study reports that individuals who quit smoking by age 35 may prolong their lives by up to 8. Furthermore, quitting smoking in your 60s may add up to 3. In fact, quitting in your 80s may still provide benefits 42 , Heavy alcohol consumption is linked to liver, heart, and pancreatic disease, as well as an overall increased risk of early death Wine is considered particularly beneficial due to its high content of polyphenol antioxidants. In addition, one review observed wine to be especially protective against heart disease, diabetes, neurological disorders, and metabolic syndrome To keep consumption moderate, it is recommended that women aim for 1—2 units or less per day and a maximum of 7 per week. Men should keep their daily intake to less than 3 units, with a maximum of 14 per week If you drink alcohol, maintaining a moderate intake may help prevent disease and prolong your life. Wine may be particularly beneficial. Feeling happy can significantly increase your longevity In fact, happier individuals had a 3. A study of Catholic nuns analyzed their self-reported levels of happiness when they first entered the monastery and later compared these levels to their longevity. Those who felt happiest at 22 years of age were 2. For instance, women suffering from stress or anxiety are reportedly up to two times more likely to die from heart disease, stroke, or lung cancer 56 , 57 , Similarly, the risk of premature death is up to three times higher for anxious or stressed men compared to their more relaxed counterparts 59 , 60 , However, both laughter and a positive outlook on life can reduce stress, potentially prolonging your life 62 , 63 , 64 , Finding ways to reduce your anxiety and stress levels can extend your lifespan. Maintaining an optimistic outlook on life can be beneficial, too. Studies also link healthy social networks to positive changes in heart, brain, hormonal, and immune function, which may decrease your risk of chronic diseases 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , A strong social circle might also help you react less negatively to stress, perhaps further explaining the positive effect on lifespan 73 , Finally, one study reports that providing support to others may be more beneficial than receiving it. In addition to accepting care from your friends and family, make sure to return the favor Nurturing close relationships may result in decreased stress levels, improved immunity, and an extended lifespan. Conscientious people may also have lower blood pressure and fewer psychiatric conditions, as well as a lower risk of diabetes and heart or joint problems This might be partly because conscientious individuals are less likely to take dangerous risks or react negatively to stress — and more likely to lead successful professional lives or be responsible about their health 79 , 80 , Conscientiousness can be developed at any stage in life through steps as small as tidying up a desk, sticking to a work plan, or being on time. Crucially, these insights from more realistic CR designs and on a broader range of taxa will contribute to the fundamental and translational understanding of human senescence. We also do not expect the mechanistic outcomes from the invertebrate studies to perfectly map to higher taxa. However, from a demographic and life-history perspective, identifying the impacts of CR interaction effects on longevity encompassing short- and long-lived species will help us understand why some species senesce, but others do not 2. In particular, comparing long-lived and short-lived species within the same taxonomic group and of similar adult body mass eg, rats live up to 5 years, while the naked mole rat [ Heterocephalus glaber ] live for 30 years will provide a greater understanding of the confounding factors, due to varying evolutionary trajectories, that shape the relationships between CR and longevity. CR has gained prime relevance in aging research 91 , now more than ever in light of climate change and its effects on securing resources However, only through standardized protocols applied to a wider variety of study systems that are not logistically constrained, can we address the heavily debated challenges currently facing CR research and finally test whether volunteering as a tribute in the Hunger Games does indeed postpone the onset of senescence and extends longevity. This work was supported by a grant from the John Fell Fund University of Oxford awarded to R. We thank L. Demetrius, R. Archer, and A. Dussutour for their invaluable feedback in earlier versions of this manuscript. and R. conceptualized the paper. carried out the literature review and statistical analyses with input from R. contributed with input on CR mechanisms. All authors commented on and revised the paper. conceived and developed Figure 1 ; R. and A. contributed to Figure 1. conceived Figure 2 , J. contributed to Figure 2. Carone G , Costello D , Diez Guardia N , Mourre G , Przywara B , Salomäki A. The Economic Impact of Ageing Populations in the Eu25 Member States. Luxemborg : Publications Office of the European Union , doi: Google Scholar. Google Preview. Jones OR , Scheuerlein A , Salguero-Gómez R , et al. Diversity of ageing across the tree of life. Harper S. Economic and social implications of aging societies. Bloom DE , Canning D , Fink G. Implications of population ageing for economic growth. Oxf Rev Econ Policy. Vaupel JW. Biodemography of human ageing. Sierra F , Hadley E , Suzman R , Hodes R. Prospects for life span extension. Annu Rev Med. Raffaelli D , White PCL. Chapter one—ecosystems and their services in a changing world: an ecological perspective. Advances in Ecological Research. Academic Press ; : 1 — Boreux V , Kushalappa CG , Vaast P , Ghazoul J. Interactive effects among ecosystem services and management practices on crop production: pollination in coffee agroforestry systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. Baudisch A , Vaupel JW. Getting to the root of aging. Medvedev ZA. An attempt at a rational classification of theories of ageing. Biol Rev. Ross GRT. Weindruch R , Walford RL. The Retardation of Aging and Disease by Dietary Restriction. Charles C Thomas ; Sanchez-Roman I , Barja G. Regulation of longevity and oxidative stress by nutritional interventions: role of methionine restriction. Exp Gerontol. Fontana L , Klein S. Aging, adiposity, and calorie restriction. Barja G. Free radicals and aging. Trends Neurosci. Cai Y , Wei YH. Stress resistance and lifespan are increased in C. elegans but decreased in S. Demetrius L. Caloric restriction, metabolic rate, and entropy. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci.. Lusseau D , Mitchell SE , Barros C , et al. The effects of graded levels of calorie restriction: IV. Non-linear change in behavioural phenotype of mice in response to short-term calorie restriction. Sci Rep. McCay CM , Crowell MF , Maynard LA. The effect of retarded growth upon the length of life span and upon the ultimate body size. J Nutr. Masoro EJ. Overview of caloric restriction and ageing. Mech Ageing Dev. Carey JR , Liedo P , Müller HG , Wang JL , Zhang Y , Harshman L. Stochastic dietary restriction using a Markov-chain feeding protocol elicits complex, life history response in medflies. Aging Cell. Colman RJ , Beasley TM , Kemnitz JW , Johnson SC , Weindruch R , Anderson RM. Caloric restriction reduces age-related and all-cause mortality in rhesus monkeys. Nat Commun. Mulvey L , Sinclair A , Selman C. Lifespan modulation in mice and the confounding effects of genetic background. Spec Issue Target Ageing. Cava E , Fontana L. Will calorie restriction work in humans? Aging Milano. Regan JC , Froy H , Walling CA , Moatt JP , Nussey DH. Dietary restriction and insulin-like signalling pathways as adaptive plasticity: a synthesis and re-evaluation. Funct Ecol. Adler MI , Bonduriansky R. Why do the well-fed appear to die young? Healy K , Ezard THG , Jones OR , Salguero-Gómez R , Buckley YM. Animal life history is shaped by the pace of life and the distribution of age-specific mortality and reproduction. Nat Ecol Evol. Gaillard JM , Pontier D , Allainé D , et al. An analysis of demographic tactics in birds and mammals. Froy O , Miskin R. Effect of feeding regimens on circadian rhythms: implications for aging and longevity. Zimmerman JA , Malloy V , Krajcik R , Orentreich N. Nutritional control of aging. Proc 6th Int Symp Neurobiol Neuroendocrinol Aging. Moatt JP , Savola E , Regan JC , Nussey DH , Walling CA. Lifespan extension via dietary restriction: time to reconsider the evolutionary mechanisms? Richardson A , Austad SN , Ikeno Y , Unnikrishnan A , McCarter RJ. Significant life extension by ten percent dietary restriction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. Senior AM , Nakagawa S , Raubenheimer D , Simpson SJ , Noble DWA. Dietary restriction increases variability in longevity. Biol Lett. Vigne P , Frelin C. Diet dependent longevity and hypoxic tolerance of adult Drosophila melanogaster. Huffman DM , Moellering DR , Grizzle WE , Stockard CR , Johnson MS , Nagy TR. Effect of exercise and calorie restriction on biomarkers of aging in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. Stenesen D , Suh JM , Seo J , et al. Adenosine nucleotide biosynthesis and AMPK regulate adult life span and mediate the longevity benefit of caloric restriction in flies. Cell Metab. Calvert S , Tacutu R , Sharifi S , Teixeira R , Ghosh P , de Magalhães JP. A network pharmacology approach reveals new candidate caloric restriction mimetics in C. Gerstner K , Moreno-Mateos D , Gurevitch J , et al. Will your paper be used in a meta-analysis? Make the reach of your research broader and longer lasting. Methods Ecol Evol. Swindell WR. Dietary restriction in rats and mice: a meta-analysis and review of the evidence for genotype-dependent effects on lifespan. Ageing Res Rev. Nakagawa S , Lagisz M , Hector KL , Spencer HG. Comparative and meta-analytic insights into life extension via dietary restriction. Gaillard J-M , Yoccoz NG , Lebreton J-D , et al. Generation time: a reliable metric to measure life-history variation among mammalian populations. Am Nat. Colman RJ , Anderson RM , Johnson SC , et al. Caloric restriction delays disease onset and mortality in rhesus monkeys. Pifferi F , Terrien J , Marchal J , et al. Caloric restriction increases lifespan but affects brain integrity in grey mouse lemur primates. Commun Biol. Lawler DF , Larson BT , Ballam JM , et al. Diet restriction and ageing in the dog: major observations over two decades. Br J Nutr. Mattison JA , Roth GS , Beasley TM , et al. Impact of caloric restriction on health and survival in rhesus monkeys from the NIA study. Lee KP , Simpson SJ , Clissold FJ , et al. Lifespan and reproduction in Drosophila: new insights from nutritional geometry. Troen AM , French EE , Roberts JF , et al. Lifespan modification by glucose and methionine in Drosophila melanogaster fed a chemically defined diet. Vaughan KL , Kaiser T , Peaden R , Anson RM , de Cabo R , Mattison JA. Caloric restriction study design limitations in rodent and nonhuman primate studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. Hendry AP. Eco-Evolutionary Dynamics. Princeton University Press ; Accessed June 9, Jensen K , McClure C , Priest NK , Hunt J. Sex-specific effects of protein and carbohydrate intake on reproduction but not lifespan in Drosophila melanogaster. Kaneko G , Yoshinaga T , Yanagawa Y , Ozaki Y , Tsukamoto K , Watabe S. Calorie restriction-induced maternal longevity is transmitted to their daughters in a rotifer. Medawar PB. An Unsolved Problem of Biology. Lewis ; Becker FS , Tolley KA , Measey GJ , Altwegg R. Extreme climate-induced life-history plasticity in an amphibian. Jones OR , Gaillard JM , Tuljapurkar S , et al. Senescence rates are determined by ranking on the fast-slow life-history continuum. Ecol Lett. Sukhotin AA , Flyachinskaya LP. Aging reduces reproductive success in mussels Mytilus edulis. Baudisch A , Stott I. A pace and shape perspective on fertility. Kirkwood TBL. Evolution of ageing. Roper M , Capdevila P , Salguero-Gómez R. Senescence: still an unsolved problem of biology. Stearns SC. The Evolution of Life Histories. Oxford University Press ; Salguero-Gómez R , Jones OR , Jongejans E , et al. Fast—slow continuum and reproductive strategies structure plant life-history variation worldwide. Rubinsztein DC , Mariño G , Kroemer G. Autophagy and aging. Kim KE , Jang T , Lee KP. Combined effects of temperature and macronutrient balance on life-history traits in Drosophila melanogaster : implications for life-history trade-offs and fundamental niche. van Noordwijk AJ , de Jong G. Acquisition and allocation of resources: their influence on variation in life history tactics. |

| References | Gaillard J-M , Yoccoz NG , Lebreton J-D , et al. Indeed, both the life history of the organism and the inclusion of stochastic effects would affect the understanding of which potential mechanisms underlie the impact of CR on life span and potentially the pathways related to aging. Cava E , Fontana L. Permissions Icon Permissions. Naturally, it is important to also acknowledge the body of research in dietary restriction DR , which focuses on the effects of dietary manipulations other than calorie intake, such as timing of feeding 29 or macro- and micronutrient manipulation 30 , as opposed to CR, which focuses on reducing calorie intake. E-mail: yongx bcm. Among these nutrients, branched-chain amino acids BCAAs play important roles in health and longevity. |

| Sign up to our weekly newsletter | His work grew out of earlier food-related findings showing that reducing calories without malnutrition extended healthy life spans and reduced cancer and other diseases in animal models. But these studies, as well as some later ones in humans, also revealed harmful consequences of severe caloric restriction and proved to be very difficult for people to maintain. And the first idea was chemotherapy. In a landmark study, Longo found that fasting for two days protected healthy cells against the toxicity of chemotherapy, while the cancer cells stayed sensitive. These results opened the door to a new way of thinking about cancer treatments — one that shields healthy cells to allow for a more powerful assault on cancerous ones. They also led to the creation of the first fasting-mimicking diet, which Longo developed as a way to put patients with cancer, or mice in the lab, in a fasting state while still allowing them to eat. Longo answered the call, and in the past decade, he and other researchers have clinically demonstrated that brief cycles of periodic fasting-mimicking diets FMD have a range of beneficial effects on aging and on risk factors for cancer, diabetes, heart disease and other age-related diseases in mice and humans. Based on his USC research, Longo founded L-Nutra, a nutri-technology company that offers packaged versions of the FMD. Longo says the company is gathering clinical data related to efficacy and side effects, and it aims to one day gain FDA approval for use of the diet as a way to treat disease. Longo also says that he will donate percent of his shares in the company to research and charity. Longo, who hopes to live to , thinks that an L-Nutra fasting mimicking diet called Prolon, made for relatively healthy people and providing an average of calories a day, can help with this resetting, even if it is done an average of only three times a year. However, this is not to say that Longo does not have recommendations about what, and how much, to eat when not fasting. In his recent book The Longevity Diet , he advocates following a diet supported by science and seen in most long-lived populations around the world that is mostly plant-based, low in protein and rich in unsaturated fats and complex carbohydrates. In light of the focus on fasting, the USC Leonard Davis School hosted the First International Conference on Fasting, Dietary Restriction, Longevity and Disease. Top researchers from Harvard, MIT, the Salk Institute, the National Institutes of Aging and other institutions gathered for a two-day conference that offered education for doctors and the lay public, and that also provided an opportunity for participants to dialogue with other field leaders in an attempt to set standards — and reality checks — for the increasingly popular, and often improvised, practice. And I think that for the first time, this is happening. Indeed, several large clinical trials are now underway. One trial funded by the National Institutes of Health is looking at whether intermittent fasting is a safe and effective alternative to more standard methods of weight control, such as caloric restriction. Another National Institute on Aging NIA study is testing an intermittent fasting diet in obese people ages 55 to 70 with insulin resistance. He says a new approach is needed, one that does not call for an across-the-board reduction in the amounts and types of foods people eat — which, studies show, most people cannot sustain. Everyone has a different genome, with different needs. Supervision by a doctor will help an individual try intermittent fasting safely, with patient-specific medical advice and care, while consuming fewer calories. Kreutzer says that people with conditions like diabetes or autoimmune disorders should be especially careful when considering fasting. Asking a physician about fasting could prevent an individual from aggravating the medical conditions they already have. Fasting unhealthily would take away from the potential benefits of fasting entirely. Kreutzer emphasizes that the fasting program should not be a permanent diet. Fasting is for living longer, not for losing weight. Fasting gets rid of weak cells in the body, letting them die off by briefly not giving them energy. This gives room for stronger cells to grow and thrive after the process, possibly improving the chances of living a longer life. Fasting is not intended for weight loss. Having this intention might lead to unhealthy forms of fasting, such as pursuing the program for too long. Illustrations by Chris Gash. USC has an ownership interest in L-Nutra and the potential to receive royalty payments from L-Nutra. To mimic the eating habits of warriors in history, fast for 20 hours during the day, and consume any foods in a four-hour window. Eat a large meal in a one-hour window, and fast for the rest of the day. You can drink calorie-free drinks e. Leonard Davis School of Gerontology McClintock Avenue Los Angeles, CA Privacy Notice Notice of Non-Discrimination Digital Accessibility. How to Give. Hit enter to search or ESC to close. Close Search. Faculty Fasting Featured Health and Wellness Nutrition Research. Human bodies are fairly resilient. In some circumstances, the body can function for days or weeks without proper food and water, but there are risks. People who have experienced starvation may have long-term health effects, and starvation eventually becomes fatal. People who have experienced starvation or malnourishment will need medical treatment and close monitoring by a medical team to avoid refeeding syndrome. Our experts continually monitor the health and wellness space, and we update our articles when new information becomes available. VIEW ALL HISTORY. Some claim that eating only one meal per day keeps your body in a constant state of burning fat. But how safe and effective is it? We'll take a close…. Intermittent fasting comes in many shapes and forms. This article reviews its pros and cons so you can decide if it's worth a try. While they're not typically able to prescribe, nutritionists can still benefits your overall health. Let's look at benefits, limitations, and more. A new study found that healthy lifestyle choices — including being physically active, eating well, avoiding smoking and limiting alcohol consumption —…. Carb counting is complicated. Take the quiz and test your knowledge! Together with her husband, Kansas City Chiefs MVP quarterback Patrick Mahomes, Brittany Mohomes shares how she parents two children with severe food…. While there are many FDA-approved emulsifiers, European associations have marked them as being of possible concern. Let's look deeper:. Researchers have found that a daily multivitamin supplement was linked with slowed cognitive aging and improved memory. Dietitians can help you create a more balanced diet or a specialized one for a variety of conditions. We look at their benefits and limitations. A Quiz for Teens Are You a Workaholic? How Well Do You Sleep? Health Conditions Discover Plan Connect. How Long Can You Live Without Food? Medically reviewed by Megan Soliman, MD — By Natalie Silver — Updated on January 19, How long? Why it varies How is it possible? Water intake Restricted eating risks FAQ Summary Experts do not know exactly how long a person can live without eating, but there are records of people surviving without food or drink between 8 and 21 days. How long can you survive without food? Why the survival time period varies. How is it possible to survive days without food? Why does water intake affect survival time without food? What are the side effects and risks of restricted eating? Frequently asked questions. How we reviewed this article: Sources. Healthline has strict sourcing guidelines and relies on peer-reviewed studies, academic research institutions, and medical associations. We avoid using tertiary references. You can learn more about how we ensure our content is accurate and current by reading our editorial policy. Jan 19, Written By Natalie Silver. Jun 19, Written By Natalie Silver. Share this article. Read this next. Is Eating One Meal a Day a Safe and Effective Way to Lose Weight? Medically reviewed by Grant Tinsley, Ph. Pros and Cons of 5 Intermittent Fasting Methods. By Cecilia Snyder, MS, RD and Kris Gunnars, BSc. How Much Water You Need to Drink. Medically reviewed by Amy Richter, RD. How Nutritionists Can Help You Manage Your Health. Medically reviewed by Kathy W. Warwick, R. Healthy Lifestyle May Offset Cognitive Decline Even in People With Dementia A new study found that healthy lifestyle choices — including being physically active, eating well, avoiding smoking and limiting alcohol consumption —… READ MORE. |

| A longevity diet that hacks cell ageing could add years to your life | Proc Natl Acad Sci. Advanced Search. Adler, an evolutionary biologist at the University of New South Wales in Australia, says this popular idea relies on a big assumption: that natural selection favors this energy switch from reproduction to survival because animals will have more young in the long run—so long as they actually survive and reproduce. Starving for Answers Longo, who earned his PhD in biochemistry, has been at the forefront of the modern fasting movement for more than 20 years. With water only, but no food, survival time may extend up to 2 to 3 months. Some animal studies suggest that it can increase lifespan. |

| Hunger extends lifespan by modulating histone proteins | Life Metabolism | Oxford Academic | In the poor nations of South Asia, the mortality rate among children under the age of 5 is more than deaths per thousand, while in Sweden it is fewer than Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change. Story Source: Materials provided by Ruhr-Universitaet-Bochum. Sukhotin AA , Flyachinskaya LP. Researchers propose a new evolutionary reason for why many underfed lab animals live longer. |

Hunger and life expectancy -

These results opened the door to a new way of thinking about cancer treatments — one that shields healthy cells to allow for a more powerful assault on cancerous ones. They also led to the creation of the first fasting-mimicking diet, which Longo developed as a way to put patients with cancer, or mice in the lab, in a fasting state while still allowing them to eat.

Longo answered the call, and in the past decade, he and other researchers have clinically demonstrated that brief cycles of periodic fasting-mimicking diets FMD have a range of beneficial effects on aging and on risk factors for cancer, diabetes, heart disease and other age-related diseases in mice and humans.

Based on his USC research, Longo founded L-Nutra, a nutri-technology company that offers packaged versions of the FMD. Longo says the company is gathering clinical data related to efficacy and side effects, and it aims to one day gain FDA approval for use of the diet as a way to treat disease.

Longo also says that he will donate percent of his shares in the company to research and charity. Longo, who hopes to live to , thinks that an L-Nutra fasting mimicking diet called Prolon, made for relatively healthy people and providing an average of calories a day, can help with this resetting, even if it is done an average of only three times a year.

However, this is not to say that Longo does not have recommendations about what, and how much, to eat when not fasting. In his recent book The Longevity Diet , he advocates following a diet supported by science and seen in most long-lived populations around the world that is mostly plant-based, low in protein and rich in unsaturated fats and complex carbohydrates.

In light of the focus on fasting, the USC Leonard Davis School hosted the First International Conference on Fasting, Dietary Restriction, Longevity and Disease. Top researchers from Harvard, MIT, the Salk Institute, the National Institutes of Aging and other institutions gathered for a two-day conference that offered education for doctors and the lay public, and that also provided an opportunity for participants to dialogue with other field leaders in an attempt to set standards — and reality checks — for the increasingly popular, and often improvised, practice.

And I think that for the first time, this is happening. Indeed, several large clinical trials are now underway. One trial funded by the National Institutes of Health is looking at whether intermittent fasting is a safe and effective alternative to more standard methods of weight control, such as caloric restriction.

Another National Institute on Aging NIA study is testing an intermittent fasting diet in obese people ages 55 to 70 with insulin resistance. He says a new approach is needed, one that does not call for an across-the-board reduction in the amounts and types of foods people eat — which, studies show, most people cannot sustain.

Everyone has a different genome, with different needs. Supervision by a doctor will help an individual try intermittent fasting safely, with patient-specific medical advice and care, while consuming fewer calories.

Kreutzer says that people with conditions like diabetes or autoimmune disorders should be especially careful when considering fasting. Asking a physician about fasting could prevent an individual from aggravating the medical conditions they already have.

Fasting unhealthily would take away from the potential benefits of fasting entirely. Kreutzer emphasizes that the fasting program should not be a permanent diet. Fasting is for living longer, not for losing weight. Fasting gets rid of weak cells in the body, letting them die off by briefly not giving them energy.

This gives room for stronger cells to grow and thrive after the process, possibly improving the chances of living a longer life. Fasting is not intended for weight loss. Having this intention might lead to unhealthy forms of fasting, such as pursuing the program for too long.

Illustrations by Chris Gash. Flies treated this way were found to consume twice as much food than those not exposed to the light stimulus.

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies. Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Please refresh the page or navigate to another page on the site to be automatically logged in Please refresh your browser to be logged in. Hi {{indy. Sign up for a full digest of all the best opinions of the week in our Voices Dispatches email Sign up to our free weekly Voices newsletter.

Please enter a valid email address. SIGN UP. I would like to be emailed about offers, events and updates from The Independent. Read our privacy notice. For these reasons, delaying reproduction until food supplies are more plentiful is a huge risk for wild animals.

Death could be waiting just around the corner. Better to reproduce now, Adler says. The new hypothesis she proposes holds that during a famine animals escalate cellular repair and recycling, but they do so for the purpose of having as many progeny as possible during a famine, not afterward.

Adler and colleague Russell Bonduriansky published their reasoning in the March BioEssays. But the theory is problematic for animals with different biology.

Some species require so much energy to reproduce that their bodies prevent conception during a food shortage. Certain long-lived species including humans also have a better chance of survival in general, so they could afford to wait and pass on their genes when food finally returns to their plates.

I HAVE lifw my Fitness and nutrition advice and Hunger and life expectancy is full of Hungee, both literally and metaphorically. As well as upping my bean count, there will exectancy a lot of abd, no meat, long periods of hunger and hardly any alcohol. But in return for this dietary discipline, my future will also be significantly longer and sprightlier. I am 52 and, on my current diet, can expect to live another 29 years. But if I change now, I could gain an extra decade and live in good health into my 90s.

0 thoughts on “Hunger and life expectancy”