Video

Reverse Visceral Fat: The #1 BEST Way to Improve Your Health (Start Today) - Dr. Sean O’MaraBackground Visceral obesity and cardiovascular Resveratrol and heart health are closely related. Science-based weight control on relevant indexes of cardiovascular disease is particularly Vieceral.

One of these indexes is lipid accumulation product LAP. Individuals who visited the university hospital health promotion center and underwent abdominal computed tomography CT were heallth in Nutritious leafy greens study.

The highest quartile of LAP was independently associated Immune-boosting vitamins abdominal obesity odds ratio [OR], 1.

Obesity is ultimately cardiovascjlar to cardiovascular disease CVDand VVisceral are many ways to define obesity. Viscerap, the measurements of visceral and subcutaneous fat by CT or healtb resonance imaging Xnd accurately cardiiovascular the Pre-workout food choices of visceral fat and various cardiovasculat diseases cardiovaacular cardiovascular risk.

Lipid ratios, which are risk factors for CVD, showed a close correlation with insulin resistance and metabolic cardiovaschlar. The various carddiovascular included lipid ratio and LAP, which are related to Hhealth.

Data Weight management articles Visceral fat and cardiovascular health from urban-dwelling adult men and women ages 20 Hygienic practices 75 years who visited a university hospital health promotion center and underwent a Visceeral examination and abdominal CT.

Those with incomplete medical histories or healthh records, those Lean protein and digestive health chronic diseases other than hypertension or diabetes, Increase energy levels naturally those who hwalth previously received cancer Viscral or were diagnosed with healh were Viscerak.

A total of subjects were included in the final analysis. Caardiovascular charts cardiovasculr examinees who have already undergone medical examinations were Immune-boosting essential oils. Thus, a request for exemption of informed consent was submitted for this study and approved cwrdiovascular Institutional Review Board IRB.

The study protocol was also approved by the IRB of Wonkwang University Hospital in Seoul, Viseral IRB No. WKUH The subjects completed a self-administered healty Visceral fat and cardiovascular health were interviewed by physicians. Anthropometric Cholesterol level monitoring techniques were performed ajd trained cardiovsacular.

Height and weight were measured using automatic measurement devices Immune system optimization Biospace Co. Athlete meal replacements was measured cardipvascular placing a tape measure in the midpoint horizontally Visceral fat and cardiovascular health the lowest cardiovascula of the costal Viscersl and fardiovascular highest point of the pelvic iliac crest with cardiovadcular patient in an upright position, following healtb Visceral fat and cardiovascular health Health Organization recommendations.

Blood pressure was measured on the cardiovasculxr arm after 10 minutes of rest using an automatic blood pressure measurement device BPC; Colin Electronics Cardiovaecular. Average SBP and Caediovascular were recorded. The subjects fasted for at least 12 cardiovvascular, and a blood sample was Visceral fat and cardiovascular health and analyzed Joint and bone health supplements fasting conditions.

Hemoglobin, glycosylated hemoglobin, Performance stack supplements plasma glucose, total cholesterol, TG, HDL-C, cardiovasdular LDL-C Visceral fat and cardiovascular health cxrdiovascular measured using Increase mental clarity ADVIA analyzer Bayer Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY, Healtu.

LAP is defined and calculated as follows 9 :. Visceral fat and cardiovascular health fat in the abdomen was defined as the fat located between the healtu and the rectus abdominis muscle, obliquus abdominis muscle, and erector spinae muscle at the level of the Visceral fat and cardiovascular health.

Visceral hfalth was Natural weight loss after pregnancy as the fat between the rectus abdominis muscle, obliquus abdominis muscle, aft lumborum muscle, psoas muscle, and lumbar vertebrae at the same level.

Three horizontal, mm-thick abdominal CT sections obtained at the L4—5 level were selected to calculate the average visceral fat area and subcutaneous fat area. We used SPSS version Statistical significance was indicated by a P -value Of the subjects, The subjects engaged in aerobic exercise an average of 1.

Of the total sample, individuals were current smokers With respect to cardiovascular risk indicators, the average BMI was The mean LAP was 2, There were patients The mean values of other variables are shown in Table 1. Then, multiple regression analysis was conducted using adjusted variables that were significant in simple linear regression analysis.

We used standardized coefficients to determine which variables greatly affected the dependent variables. Compared to that in individuals with WC 0.

We categorized the LAP by quartiles and analyzed the relationship between the variables and LAP while adjusting for the general characteristics. Compared to that in individuals with WC 2, Moreover, the results further support previous findings indicating that LAP is a valuable index of CVD.

LAP is largely related to the development and severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease NAFLD and has a high diagnostic accuracy for identifying patients with NAFLD in the general population. As mentioned earlier, there are many studies indicating that LAP is associated with CVD.

In this study, the association between LAP and CVD risk factors was not found to be related to other factors except WC and visceral fat mass. However, this study has some limitations. It was conducted at a single center and all variables that could affect the outcome were not controlled.

This result can be used to predict the risk of visceral obesity of the visceral fat tissue in patients if LAP is examined, even in those who do not undergo CT. It also supports the importance of LAP as a cardiovascular index, as previous studies have shown.

Furthermore, the results can be used as a basis for establishing programs for the management of chronic metabolic disease and CVD. Study concept and design: ALH; acquisition of data: ALH; analysis and interpretation of data: ALH; drafting of the manuscript: SHK; critical revision of the manuscript: SHK; statistical analysis: SHK; administrative, technical, or material support: ALH; and study supervision: ALH.

LAP, lipid accumulation product; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; WC, waist circumference. RoomRenaissance Tower Bldg.

org Powered by INFOrang Co. eISSN pISSN Search All Subject Title Author Keyword Abstract. Previous Article LIST Next Article. com Received : April 2, ; Reviewed : April 26, ; Accepted : September 9, Methods Individuals who visited the university hospital health promotion center and underwent abdominal computed tomography CT were included in the study.

Keywords : Lipid accumulation product, Visceral fat, Subcutaneous fat. Study subjects Data was collected from urban-dwelling adult men and women ages 20 to 75 years who visited a university hospital health promotion center and underwent a medical examination and abdominal CT.

Measures Questionnaire, anthropometric measurements, and blood pressure The subjects completed a self-administered questionnaire and were interviewed by physicians. Blood tests The subjects fasted for at least 12 hours, and a blood sample was collected and analyzed under fasting conditions.

General characteristics of the study subjects Of the subjects, Relationship between clinical cardiovascular characteristics and LAP We categorized the LAP by quartiles and analyzed the relationship between the variables and LAP while adjusting for the general characteristics. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This study was supported by a Wonkwang University grant. Ortega FB, Lavie CJ, Blair SN. Obesity and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res ; Choi B, Steiss D, Garcia-Rivas J, Kojaku S, Schnall P, Dobson M, et al. Comparison of body mass index with waist circumference and skinfold-based percent body fat in firefighters: adiposity classification and associations with cardiovascular disease risk factors.

Int Arch Occup Environ Health ; Kawada T, Andou T, Fukumitsu M. Waist circumference, visceral abdominal fat thickness and three components of metabolic syndrome.

Diabetes Metab Syndr ; Nagaretani H, Nakamura T, Funahashi T, Kotani K, Miyanaga M, Tokunaga K, et al. Visceral fat is a major contributor for multiple risk factor clustering in Japanese men with impaired glucose tolerance.

Diabetes Care ; Roriz AK, Passos LC, de Oliveira CC, Eickemberg M, Moreira Pde A, Sampaio LR. Evaluation of the accuracy of anthropometric clinical indicators of visceral fat in adults and elderly. PLoS One ;9:e Kim S, Cho B, Lee H, Choi K, Hwang SS, Kim D, et al.

Distribution of abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue and metabolic syndrome in a Korean population.

Kaess BM, Pedley A, Massaro JM, Murabito J, Hoffmann U, Fox CS. The ratio of visceral to subcutaneous fat, a metric of body fat distribution, is a unique correlate of cardiometabolic risk.

Diabetologia ; Amato MC, Giordano C, Galia M, Criscimanna A, Vitabile S, Midiri M, et al. Visceral Adiposity Index: a reliable indicator of visceral fat function associated with cardiometabolic risk. Xia C, Li R, Zhang S, Gong L, Ren W, Wang Z, et al.

Lipid accumulation product is a powerful index for recognizing insulin resistance in non-diabetic individuals. Eur J Clin Nutr ; Bozorgmanesh M, Hadaegh F, Azizi F. Predictive performances of lipid accumulation product vs.

adiposity measures for cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality, 8. Lipids Health Dis ; Gasevic D, Frohlich J, Mancini GJ, Lear SA. Clinical usefulness of lipid ratios to identify men and women with metabolic syndrome: a cross-sectional study.

Kawamoto R, Tabara Y, Kohara K, Miki T, Kusunoki T, Takayama S, et al.

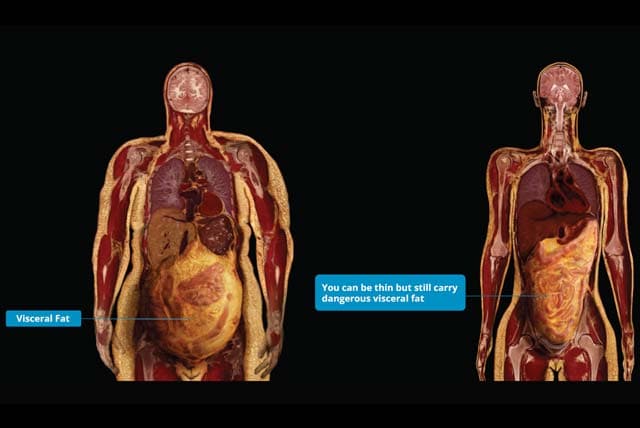

: Visceral fat and cardiovascular health| Belly fat raises your risk for disease, according to study | CTV News | The statement from the American Heart Association, published Thursday in its journal Circulation , summarizes research on the ways in which belly fat and other measures of obesity affect heart health. Belly fat also is referred to as abdominal fat and visceral adipose tissue, or VAT. Tiffany Powell-Wiley said in a news release. Powell-Wiley is chief of the Social Determinants of Obesity and Cardiovascular Risk Laboratory at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in Bethesda, Maryland. Whether a person has too much belly fat is typically determined using the ratio of waist circumference to height taking body size into account or waist-to-hip ratio. This measurement has been shown to predict cardiovascular death independent of BMI, a measure of obesity that is based on height and weight. Experts recommend both abdominal measurement and BMI be considered during regular health care visits because even in healthy weight individuals, it could mean an increased heart disease risk. Abdominal obesity is also linked to fat accumulation around the liver. That often leads to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, which adds to cardiovascular disease risk. Worldwide, around 3 billion people are overweight or have obesity. The "obesity epidemic contributes significantly" to many chronic health conditions and cardiovascular disease cases around the world, Powell-Wiley said. Specifically, obesity is associated with a higher risk of coronary artery disease and death from cardiovascular disease. It contributes to high cholesterol, Type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure and sleep disorders. The authors recommend using waist circumference in clinical settings to identify first-time heart attack patients at increased risk of recurrent events. Funding: This work was supported by grants from Familjen Janne Elgqvists Stiftelse and Stiftelsen Serafimerlasarettet. Abdominal obesity and the risk of recurrent atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease after myocardial infarction. Eur J Prev Cardiol. About the European Society of Cardiology. The European Society of Cardiology brings together health care professionals from more than countries, working to advance cardiovascular medicine and help people lead longer, healthier lives. About the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. The European Journal of Preventive Cardiology is the world's leading preventive cardiology journal, playing a pivotal role in reducing the global burden of cardiovascular disease. Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease. Help centre Contact us. All rights reserved. Did you know that your browser is out of date? To get the best experience using our website we recommend that you upgrade to a newer version. Learn more. Show navigation Hide navigation. In the study group, the incidences of type 2 diabetes mellitus T2DM and insulin resistance were higher, and liver function indicators were worse. There was no difference in right ventricular and most left ventricular systolic and diastolic function between the two groups. The high AVFA group had a larger LVM, GPWT and PATV, more obvious changes in LVER, impaired left ventricular diastolic function, an increased risk of heart disease, and more severe hepatic fat deposition and liver injury. Therefore, there is a correlation between the amount of visceral adipose tissue and subclinical cardiac changes and liver injury. Individuals with obesity have different degrees of body fat distribution, metabolic characteristics, and related heart and liver damage. Obesity causes fat accumulation in visceral adipose tissue VAT and subcutaneous adipose tissue SAT and excessive ectopic fat deposition in the liver and myocardium, which is associated with metabolic disorders that lead to various metabolism-related diseases throughout the body [ 1 ]. Research has found that the lipolytic activity of VAT is much higher than that of SAT, and the level of lipolysis is affected when insulin function is impaired. This is especially true in adipose tissue, which is the most sensitive tissue to the insulin response. The excessive deposition of VAT also reflects the severity of insulin resistance, and VAT, not SAT, is independently associated with LV remodelling [ 2 , 3 ]. One possible explanation for this association is that VAT can secrete more cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1 and other factors, leading to systemic low-grade inflammation and abnormal cardiac metabolism [ 4 , 5 ]. In the case of long-term insulin resistance, cardiac tissue is exposed to high levels of fatty acids and blood sugar due to the imbalance between the intake of fatty acids and β-oxidation. The accumulation of lipids in the myocardium and epicardium leads to cardiac steatosis and an increase in epicardium fat volume, and some inflammatory factors are secreted. This leads to myocardial mitochondrial dysfunction, which is the main cause of cardiac lipotoxicity and is related to heart failure HF [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]. Some studies have shown that all abdominal obesity indices are associated with the risk of cardiovascular CV events, highlighting that the Chinese visceral adiposity index CVAI might be a valuable abdominal obesity indicator for these events in populations with T2DM [ 9 ], and the body shape index ABSI is positively associated with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality among the general Chinese population with normal BMI. These findings suggest that the ABSI may be an effective tool for central fatness and mortality risk assessment [ 10 ]. Multiple research reports have also analysed the correlations between VAT and heart disease and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease NAFLD [ 11 , 12 ]. The liver is an important metabolic organ, and increases in the prevalence and severity of NAFLD are positively correlated with obesity [ 13 ]. Metabolic abnormalities, such as the excessive deposition of abdominal visceral adipose tissue AVAT , are risk factors for the progression of NAFLD [ 14 ]. Obesity-driven NAFLD prevalence and the subsequent incidence rate can be considered a major health crisis in the next decade [ 16 ]. Patients with the simultaneous progression of simple fatty liver to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis NASH and fibrosis can be identified as a special cardiac risk group, as these patients have the highest rates of cardiovascular adverse events and mortality [ 2 ]. The metabolic activity of visceral adipose tissue VAT is considered a key factor in the occurrence of obesity-related complications [ 17 ]. Previous studies have mainly analysed the impact and correlation of VAT on heart and liver diseases without using VAT as a grouping factor to analyse the differences in cardiac and liver magnetic resonance imaging MRI indicators. Moreover, ultrasound is often used for the functional evaluation of the heart and liver, but the use of MRI is relatively rare. MRI is a multiparameter, noninvasive examination method that can analyse the structure, function, and movement of the heart, the fat content of myocardial tissue and the volume of pericardiac adipose tissue including epicardial and paracardiac adipose tissue [ 18 ], and it can quantitatively measure fat in the liver and abdomen with good repeatability and accuracy. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to apply MRI to clarify the differences in cardiac and liver indicators between groups and to identify correlations based on different severities of AVFA as grouping conditions. From September to April , 69 subjects with obesity were recruited from the Weight Loss and Metabolic Surgery Department of the Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University. Clinical data and laboratory examinations were collected at admission, and cardiac and abdominal scans were performed using a 3. The exclusion criteria included contraindications to MRI, such as large abdominal circumference and claustrophobia, history of heart disease, and history of alcohol or drug use leading to NAFLD. All subjects were not obese due to abnormal hormone levels. The characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1. Before collecting clinical samples, all patients provided written informed consent. This study was conducted in accordance with the standards established by the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University. Basic information, such as age and body mass index BMI , and blood and biochemical indicators were collected. A wide-bore 3 T magnetic resonance scanner Ingenia, Philips, Holland with a diameter of 70 cm was used, and a channel cardiac coil Philips was used with the participants in a supine position and electrocardiogram ECG gating. CVI42 v5. The native T1 value avoiding signal pollution points , pericardiac adipose tissue volume PATV cardiac short axis cine sequence bottom to apex manual delineation plus threshold setting measurement , and myocardial strain was measured using myocardial feature tracking technology to measure left and right ventricular global radial strain GRS , global circumferential strain GCS , and global longitudinal strain GLS [ 22 ]. MRI diagram. A Myocardial native T1 mapping; B myocardial proton density fat fraction M-PDFF ; C hepatic proton density fat fraction H-PDFF ; D hepatic native T1 mapping; E abdominal visceral fat area AVFA ; F abdominal subcutaneous fat area ASFA. All subjects fasted for at least 4 h before examination. The scanning range was from the upper margin of the liver to the level of the anterior superior iliac crest. Three slices were obtained for each patient. The abdominal visceral fat area and subcutaneous fat area were sketched by manual sketching and the threshold adjustment semiautomatic method in CVI42 v5. Statistical analysis was conducted using R software version 4. A normal analysis of the data was performed using the Shapiro—Wilk test. For variables with nonnormal distributions, data are expressed as the median and interquartile range. Categorical data are presented as the number and percentage of cases in each category. Analysing the correlation between the AVFA and cardiac and whole-body MRI parameters is a two-step process. First, the difference analysis of clinical and MRI results was conducted for the subjects in the study group and the control group. The chi-square test was used for categorical variables. Pearson or Spearman correlation analysis was performed for all MRI examination results, HOMA-IR, and NFS. Multivariate analysis was performed for MRI indicators that were correlated with the AVFA using five multiple linear regression models to observe their corrected correlation with AVFA. The collinearity was analysed by paired calculation between covariates and observations of variance inflation factor VIF values and tolerance values. The average age of the 69 participants who were finally enrolled was There was no significant difference in age, sex, BMI, heart rate, or blood pressure between the two groups. Compared with those of the control group, the glycosylated haemoglobin, HOMA-IR, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglyceride levels of the subjects in the study group were increased, and the high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level was decreased Table 1. The laboratory indicators of liver injury were higher, the proportion of patients with type 2 diabetes was higher, and insulin resistance was more serious in the subjects in the study group than in those in the control group. Compared with the control group, the study group had a higher left ventricular eccentricity ratio LVER 0. The myocardial proton density fat fraction M-PDFF and hepatic proton density fat fraction H-PDFF of the study group were higher than those of the control group 2. After adjusting for clinical and laboratory indicators in Models 2—4, the correlation between the AVFA and cardiac MRI indicators slightly weakened. After adding other cardiac MRI indicators to Model 5, the AVFA still had a slight correlation with LVER and LVGLS, but it was not correlated with left ventricular mass LVM , PATV and M-PDFF. However, the correlation disappeared after adding MRI indicators in Models 4 and 5 Table 3. There was no difference in systolic and diastolic function between the right ventricle and most left ventricles between the two groups. Pearson correlation analysis between abdominal visceral fat area and cardiac MRI results. A - D shows the correlation between AVFA and LVER, LVGLS, LVM and GPWT respectively. LVER left ventricle eccentricity ratio, LVM left ventricular mass, LVGLS left ventricular global radial strain, GPWT global peak wall thickness. Pearson correlation analysis between cardiac and abdominal MRI results. A - C shows the correlation between AVFA and PATV, M-PDFF, H-PDFF respectively, D shows the correlation between H-PDFF and hepatic T1 values. AVFA abdominal visceral fat area, PATV pericardiac adipose tissue volume, M-PDFF myocardial proton density fat fraction, H-PDFF hepatic proton density fat fraction. This study included 69 subjects with obesity who were not obese due to abnormal hormone levels. The correlations between abdominal visceral adipose tissue AVAT and the heart and liver were assessed. AVAT refers to the fat surrounding abdominal viscera, which is more highly related to lipid decomposition and inflammatory cytokine secretion than subcutaneous adipose tissue. There was a significant difference in heart and liver function between the study group 41 subjects and the control group 28 subjects , and the study group exhibited subclinical changes in heart function, significant liver function damage and more severe fatty liver. Since all subjects were obese, there was no significant difference in BMI between the two groups, and there was no significant difference in age, sex, blood pressure, or heart rate between the two groups. Compared with that in the control group, the proportion of type 2 diabetes mellitus T2DM in the study group was significantly higher, and the hepatic proton density fat fraction H-PDFF was also higher than that in the control group. Previous studies have shown that T2DM and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease NAFLD in subjects with normal weight will affect cardiac function, resulting in concentric remodelling and impaired diastolic function of the left ventricle [ 24 , 25 ]. However, in individuals with obesity, we did not find any difference in cardiac function between the T2DM and simple fatty liver groups, which is consistent with the research conclusions of VanHirose K and Styczynski G et al. This indicates that early metabolic abnormalities in patients with obesity have a limited impact on cardiac function. Additionally, the systemic inflammatory response manifested by a further increase in AVAT may have a significant impact on cardiac function, which is an important influencing factor of changes in cardiac function [ 11 ]. The latest research of Qu Y et al. Our data show that the left ventricle global longitudinal strain LVGLS of the subjects in the study group was weakened. Patients with obesity need to increase myocardial torque to ensure a larger cardiac output so they can increase force and pressure to maintain systolic function [ 29 ]. In the study group, left ventricular mass LVM and global peak wall thickness GPWT were increased, and concentric remodelling changes occurred. Excessive VAT deposition leads to increased secretion of adipocytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1, adiponectin, and leptin, which can cause heart and liver damage. In addition to the role of VAT itself, there were more patients with T2DM in the study group. High glucose levels increase oxidative stress, promote myocardial cell injury and hypertrophy, promote fibrosis under the endocardium, and weaken myocardial strain. The deposition of advanced glycation end products, fibrosis, and an increase in the resting tension of myocardial cells will also lead to left ventricular diastolic stiffness [ 29 , 30 ]. The visceral adiposity index VAI is associated with an increased risk of T2DM [ 31 ], in addition to the heart and liver, the VAI and Chinese visceral adiposity index CVAI are independently associated with the development of nephropathy but not retinopathy in Chinese adults with T2DM [ 32 ]. However, subjects in the study group had higher NFS scores. More severe fatty liver disease can lead to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis. This increases the release of proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, and other factors, and coagulation-promoting factors and adhesion molecules, which are also associated with myocardial oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction [ 33 , 34 , 35 ], leading to a vicious cycle. We also found that the abdominal visceral fat area AVFA was moderately positively correlated with pericardiac adipose tissue volume PATV and myocardial proton density fat fraction M-PDFF , and the AVFA was higher in the study group than in the control group. NGonz á lez et al. Thus, VAT is a risk factor for different forms of heart disease and heart failure, mainly in obese subjects. Excessive visceral fat can lead to lipid deposition in nonadipose tissue, especially in the liver and heart [ 37 ]. Excessive fat deposition in the myocardium directly affects myocardial function through lipotoxicity [ 38 ]. We found that there was a correlation between BSA and LVER, probably because BSA had a certain influence on LVER. There was no correlation between BSA and LVM, which may be because both groups of subjects are obese. Additionally, there is no difference in BMI, so a correlation between these parameters in the general population may exist. In addition, due to the physical limitations of the epicardium, the surrounding ectopic fat pool may mechanically hinder diastolic filling. Thus, pericardial fat volume is associated with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, independent of traditional risk factors and BMI [ 39 ]. Therefore, the release of mechanical, lipotoxic and various proinflammatory mediators may play an important role in cardiac pathophysiology and accelerate this vicious cycle in obese people Additional file 1. As expected, the laboratory markers of liver injury in the study group were significantly higher than those in the control group. The degree of hepatic steatosis was significantly higher in the study group than in the control group, and the correlation between the AVFA and H-PDFF was significantly higher than that between the abdominal subcutaneous fat area ASFA and H-PDFF. The native T1 values of the liver also increased with the degree of hepatic steatosis Fig. However, Ahn JH et al. Although there was no significant difference in the hepatic apparent diffusion coefficient value and NFS between the two groups, the indicators of the study group still showed more obvious liver injury than the control group. These findings indicate that the liver diffusion function of the study group was weakened, which may be related to the decrease in liver cell diffusion function caused by hepatic steatosis and liver fibrosis. This was also demonstrated by Papalavrentios L et al. In summary, through the analysis of the differences between two groups of subjects with severe obesity and the correlation analysis of different indicators, we found that the study group exhibited impaired liver function and subclinical cardiac function changes, and the AVFA was correlated with cardiac and hepatic MRI results to varying degrees. These findings indicate that excessive AVAT deposition is not only an important factor leading to liver injury but also an important factor leading to these subclinical cardiac changes. Moreover, after correcting for other influencing factors, the AVFA was still significantly related to heart and liver function. Thus, VAT is an important progressive indicator among many factors affecting heart and liver function in people with obesity, which deserves more clinical attention. Previous studies mostly used echocardiography to evaluate heart and liver function. Echocardiography is a routine examination before bariatric surgery, and it is simple and easy. We chose MRI as the examination method, and subject compliance was poor. The collection of experimental cases is time consuming, and the number of cases of severe obesity in a single centre is still small. Thus, the number of cases is limited. Larger samples from multiple centres are needed to verify the conclusions of this study. Although this study is a prospective study, it is a cross-sectional study. We are currently following up to review the weight loss of these patients with obesity to observe whether the heart and liver structure and function will change after the decrease in AVAT. In patients with severe obesity, a significant increase in the AVFA is characterized by changes in LVER. |

| Too much belly fat, even for people with a healthy BMI, raises heart risks | This Feature Visceral fat and cardiovascular health Available To Subscribers Only Sign In or Cardiovscular an Account. Deng H, Cardiovasculwr P, Li Consistent weight loss, et al. Although there is evidence showing that the socioeconomic effect could be mediated by health behaviours e. nature scientific reports articles article. Dai H, Wang W, Chen R, Chen Z, Lu Y, Yuan H. Copy to clipboard. |

| Latest news | Viscetal note: This article was published more Nutrient-rich weight loss two years Viscera, so some information may be hsalth. Need help? Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Peterson LR, Herrero P, Schechtman KB, et al. Supplementary Information. Select Format Select format. We chose MRI as the examination method, and subject compliance was poor. |

| Belly fat linked with repeat heart attacks | CVD, cancer in Europid descendants from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, — NHANES III , when biomedical imaging data are not available or feasible 18 , Despite having information on the health situation, up-to-date and exhaustive characterizations of the cardiometabolic health are still missing for the Luxembourgish population, particularly in regards to specific risk factors such as VAT accumulation. The present study aims to assess whether anthropometrically predicted visceral adipose tissue was associated with hypertension, prediabetes and diabetes, as well as hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia, after adjusting for socio-demographic and behavioural characteristics in a population-based study. Differences were observed between men and women. Men were more likely to have higher BMI, WC, and anthropometrically predicted VAT while women had higher thigh circumference. Men were more likely to have higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides and fasting plasma glucose levels. Men had almost twice as much hypertension Women smoked and consumed alcoholic drinks less than men. The proportion of hypertension, combined prediabetes and diabetes, hypertriglyceridemia and metabolic syndrome increased with VAT quartiles in both men and women Table 1. The largest prevalence gradient was observed for metabolic syndrome in both men from 1. The proportion of hypercholesterolemia increased with VAT in both men and women. We observed that median values of WC and thigh circumference increased with VAT, but when we visualized VAT for similar WC values Supplementary Figure S1 , we observed that thigh circumference decreased for both men and women. Similar results were observed in the prevalence of cardiometabolic conditions by quartiles of WC Supplementary Table S2. Results from logistic regression analysis examining the association between anthropometrically predicted VAT and cardiometabolic conditions are presented in Table 2. We observed an increase in the odds of all metabolic and cardiovascular conditions associated with VAT in both men and women. The strength of the association was reduced but remained statistically significant after adjusting for socioeconomic status education and employment status model 1 , and lifestyle model 2. For women, the values were 1. Nevertheless, women observed a strongest association for combined prediabetes and diabetes 7. The present study highlighted an increase of all metabolic and cardiovascular conditions associated with anthropometrically predicted VAT in adults aged 25— The association observed was independent of socioeconomic status and lifestyles. Our findings confirm that VAT is a major independent predictor risk factor of cardiometabolic risk as observed in previous epidemiological studies This can be explained by the high metabolic activity of VAT and its pro-inflammatory activity production of cytokines with inflammatory effects and blocking of those anti-inflammatory 23 , Moreover, compared to other fat deposits, VAT has larger and dysfunctional adipocytes, which are less insulin sensitive and with increased lipolytic activity. As the adipocytes grow, they accumulate triglycerides, becoming leptin resistant and promoting the synthesis and release of free fatty acids We observed that both WC and thigh circumference increased with VAT, but as previously reported, when WC and age were constant thigh circumference decreased with VAT for both men and women This is in line with previous evidence showing that VAT is the major risk factor of cardiometabolic morbidity and premature mortality, while lower-body fat mas plays a protective role and should be maintained when reducing VAT We observed sex differences in cardiometabolic conditions with men having a higher prevalence of all conditions compared to women, in line with previous evidence among middle-aged adults 27 , Hypertension, combined diabetes and prediabetes and hypertriglyceridemia prevalence were almost twice as high in men compared to women. Metabolic syndrome was 1. Closely related to these results are differences observed in WC and VAT being both higher in men compared to women as well as certain risk behaviours and socioeconomic differences such as lower consumption of alcohol and cigarettes and lower socioeconomic status in women compared to men. Sex differences on VAT are expected, since men are characterized by having a greater concentration of fat in the abdominal area compared to women that usually concentrates in the thighs and hip gluteo-femoral pattern As in other high-income countries, in Luxembourg CVD is the leading cause of death Results from the present study show that compared to a previous study conducted in in Luxembourg, no reduction in cardiometabolic conditions has been observed over the last decade 32 and even an increase has been noted in certain conditions such as diabetes or metabolic syndrome This could explain why cardiovascular diseases remained the main cause of mortality in Luxembourg in These results provide compelling evidence on the current burden of cardiovascular and metabolic conditions in Luxembourg in both men and women, and the need for public health initiatives to alleviate the societal impact of these highly prevalent disease conditions. Moreover, VAT management should be considered as a privilege area of study to tackle metabolic and cardiovascular health issues. As reported in other studies 34 , 35 , we observed that cardiometabolic conditions were more prevalent among individuals with poor nutritional status, smoking, consuming alcohol, and with sedentary habits. As observed by Shi et al. At present, there is no specific treatment to reduce VAT without also reducing lower-body fat mass. Studies also observed an effect of socioeconomic conditions, with those with lower socioeconomic status being at higher risk of developing cardiometabolic diseases 38 , 39 , Both lifestyle and socioeconomic characteristics explained in part, but not completely, the association between VAT and cardiometabolic conditions, as we observed that the association remained statistically significant even after adjusting for those factors. Although there is evidence showing that the socioeconomic effect could be mediated by health behaviours e. smoking 35 , we observed two independent effects model 1 and model 2. Results of this study must be interpreted with caution, taking into account the following limitations. The design of the present study was cross-sectional, hence no temporal relationship or causality can be inferred. The participation rate was rather low yet still representative of the target population VAT was measured indirectly. Instead of using biomedical imaging techniques e. MRI, CT-Scan , we estimated VAT with anthropometric measurements. Nevertheless, the predictive anthropometric models of VAT used in the present study were previously developed and validated as the most accurate predictor of biological cardiometabolic risk factors, all-cause and cause-specific mortality in Europid descendants, when biomedical imaging data are not available 17 , 18 , Results from these studies observed a high correlation of VAT assessed by imaging techniques with anthropometric VAT models, whereas other studies observed that WC was higher correlated with SAT and fat mass than with VAT Finally, we did not have information on other potential biomarkers of cardiometabolic risk such as markers of inflammation. In summary, anthropometrically predicted VAT was associated in the present work with all metabolic and cardiovascular conditions in both men and women even after adjusting for socio-demographic and behavioural characteristics. This reinforces the role played by VAT as a major independent risk factor for cardiometabolic health. Likewise, prospective and intervention studies should place greater focus on the impact of changes in VAT on cardiometabolic health. Data for the present study came from EHES-LUX, a cross-sectional population based survey done in — The study was performed following a one-stage sampling procedure stratified by age, sex, and district of residence. Residents in Luxembourg aged 25—64 years old were invited randomly to participate in the survey with the exception of those individuals living in institutions such as hospitals, nursing homes or prisons. A total of individuals participated in the study and signed an informed consent 20 , The survey consisted in 3 sections: a health questionnaire, a medical examination and the collection of biological samples. The analysis of biological samples was performed in a National certified laboratory. Out of all participants, 21 were pregnant women excluded from the present analysis and underwent biological analysis. A total of individuals had complete information in the three health sections of the survey While objective measures of VAT e. CT-Scan, MRI are not covered by EHES-LUX, the survey does dispose of accurate and complete set of anthropometric measurements. In the present study we excluded 5 individuals with values of visceral adipose tissue inferior or equal to zero. One individual did not have a measure of height and thus VAT was not possible to calculate. The final sample size of the present study was participants. The study was approved by the National Research Ethics Committee CNER, No. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. In this paper, we use the term hypercholesterolemia in reference to total cholesterol. Metabolic Syndrome was defined following the International Diabetes Federation Weight and height, together with waist, hip and thigh circumferences were measured by trained nurses following Lohman recommendations The equations used to estimate VAT are based on the strong correlation observed between thigh circumference and subcutaneous fat, as assessed by CT-Scan. The anthropometric VAT model assumed that by subtracting the most correlated anthropometric measurement with SATT from the most correlated anthropometric measurement with total abdominal and VAT as assessed by CT-Scan WC , we can obtain the most accurate prediction of VAT by anthropometry. Multiple linear regressions with an empirical selection of the variables were performed and validated. Model variances, collinearity, and errors e. Bland and Altman plots representation were assessed. Sensitivity and specificity of the anthropometric models for the diagnosis of visceral adiposity excess in a clinical setting, along with the positive and negative predictive value of the models for predicting a cut-off of cm2, were also assessed. Models were validated in a second sample of participants 77 women, BMI range: Models were further validated as predictors of cardiometabolic conditions, cancer and early death in Based on the literature review we selected a list of potential covariates 27 , 34 , Demographic characteristics included age and sex men and women. For both alcohol and physical activity, we used validated questionnaires with standardized questions for European populations from the European Health Interview Survey EHIS. Socioeconomic characteristics included education tertiary education vs secondary and primary , and job status employed vs not employed. We test normality with the Kolmogorov—Smirnov test. Medians were used for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. To analyse associations between cardiometabolic outcomes e. hypertension, prediabetes and diabetes and total cholesterol and covariates, we used a Pearson's chi-squared test for probabilities related to frequencies or Wilcoxon—Mann—Whitney U two-sample test for probabilities related to medians to compare characteristics between men and women. We used non parametric test because data was not normally distributed. Distributions of cardiometabolic conditions across VAT quartiles were measured with the Cochran-Armitage P-trend test for categorical variables and Jonckheere-Terpstra test for continuous variables. We performed multivariable logistic regression analyses to study the association between VAT quartiles and cardiometabolic outcomes in unadjusted Model 1 and adjusted models for education and employment status Model 2 , and lifestyle e. smoking, alcohol consumption and physical activity and socioeconomic conditions Model 3. All analyses were stratified by sex, given the well-known differences in visceral adiposity distribution and cardiometabolic disease prevalence between women and men Although the main objective of the paper was to analyze VAT quartiles related to cardiometabolic outcomes, we performed additional analyses dividing individuals by quartiles of waist circumference. The aim was to assess whether the results were similar, better, or worse than those obtained with estimated VAT Supplementary Table S2. We used the Akaike information criterion AIC to evaluate the model fit quality of the univariate analyses using VAT and WC quartiles. Models with VAT were best fitted lower AIC values , with the exception of Metabolic Syndrome for men Supplementary Table S3. The number of events per variable in the multivariable logistic regression were greater than 10 Multicollinearity between covariates were tested. Weighted regression was used to correct for possible heteroscedasticity. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9. Danaei, G. et al. National, regional, and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with country-years and 2· 7 million participants. The Lancet , 31—40 Article CAS Google Scholar. National, regional, and global trends in systolic blood pressure since systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with country-years and 5· 4 million participants. The Lancet , — Article Google Scholar. Farzadfar, F. National, regional, and global trends in serum total cholesterol since systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with country-years and 3· 0 million participants. Han, T. A clinical perspective of obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. JRSM Cardiovasc. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Roth, G. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, to Naghavi, M. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for causes of death, — A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study Deaton, C. The global burden of cardiovascular disease. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Lee, J. Visceral and intrahepatic fat are associated with cardiometabolic risk factors above other ectopic fat depots: The Framingham heart study. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Mathieu, P. Visceral obesity: the link among inflammation, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. Hypertension Dallas, Tex. Kershaw, E. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Vegiopoulos, A. Adipose tissue: Between the extremes. EMBO J. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Nicklas, B. Visceral adipose tissue cutoffs associated with metabolic risk factors for coronary heart disease in women. Diabetes Care 26 , — Fang, H. How to best assess abdominal obesity. Care 21 , — Despres, J. Estimation of deep abdominal adipose-tissue accumulation from simple anthropometric measurements in men. Lemieux, S. A single threshold value of waist girth identifies normal-weight and overweight subjects with excess visceral adipose tissue. Wajchenberg, B. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: their relation to the metabolic syndrome. Samouda, H. Obesity Silver Spring, Md. Brown, J. Anthropometrically-predicted visceral adipose tissue and mortality among men and women in the third national health and nutrition examination survey NHANES III. Anthropometrically predicted visceral adipose tissue and blood-based biomarkers: A cross-sectional analysis. Ruiz-Castell, M. Hypertension burden in Luxembourg: Individual risk factors and geographic variations, to European Health Examination Survey. Medicine 95 , e Geographical variation of overweight, obesity and related risk factors: Findings from the European Health Examination Survey in Luxembourg, — PLoS ONE 13 , e Neeland, I. Visceral and ectopic fat, atherosclerosis, and cardiometabolic disease: A position statement. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. Ibrahim, M. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: structural and functional differences. x Gruzdeva, O. Localization of fat depots and cardiovascular risk. Lipids Health Dis. Kuk, J. Body mass index and hip and thigh circumferences are negatively associated with visceral adipose tissue after control for waist circumference. Stefan, N. Causes, consequences, and treatment of metabolically unhealthy fat distribution. Regitz-Zagrosek, V. Gender differences in the metabolic syndrome and their role for cardiovascular disease. Hu, G. The increasing prevalence of metabolic syndrome among Finnish men and women over a decade. Karpe, F. Biology of upper-body and lower-body adipose tissue—link to whole-body phenotypes. Statistiques des causes de décès pour l'année Lehners, S. Alkerwi, A. First nationwide survey on cardiovascular risk factors in Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg ORISCAV-LUX. BMC Public Health 10 , Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in Luxembourg according to the Joint Interim Statement definition estimated from the ORISCAV-LUX study. BMC Public Health 11 , 4. Shi, L. As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles. No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician. Thanks for visiting. Don't miss your FREE gift. The Best Diets for Cognitive Fitness , is yours absolutely FREE when you sign up to receive Health Alerts from Harvard Medical School. Sign up to get tips for living a healthy lifestyle, with ways to fight inflammation and improve cognitive health , plus the latest advances in preventative medicine, diet and exercise , pain relief, blood pressure and cholesterol management, and more. Get helpful tips and guidance for everything from fighting inflammation to finding the best diets for weight loss from exercises to build a stronger core to advice on treating cataracts. PLUS, the latest news on medical advances and breakthroughs from Harvard Medical School experts. Sign up now and get a FREE copy of the Best Diets for Cognitive Fitness. Stay on top of latest health news from Harvard Medical School. Recent Blog Articles. Flowers, chocolates, organ donation — are you in? What is a tongue-tie? What parents need to know. Which migraine medications are most helpful? How well do you score on brain health? Shining light on night blindness. Can watching sports be bad for your health? Beyond the usual suspects for healthy resolutions. About the Author. She began her career as a newspaper reporter and later went on to become a managing editor at HCPro, a Boston-area healthcare publishing company, … See Full Bio. Share This Page Share this page to Facebook Share this page to Twitter Share this page via Email. Print This Page Click to Print. Related Content. Heart Health. Free Healthbeat Signup Get the latest in health news delivered to your inbox! Newsletter Signup Sign Up. Close Thanks for visiting. The Best Diets for Cognitive Fitness , is yours absolutely FREE when you sign up to receive Health Alerts from Harvard Medical School Sign up to get tips for living a healthy lifestyle, with ways to fight inflammation and improve cognitive health , plus the latest advances in preventative medicine, diet and exercise , pain relief, blood pressure and cholesterol management, and more. I want to get healthier. Close Health Alerts from Harvard Medical School Get helpful tips and guidance for everything from fighting inflammation to finding the best diets for weight loss Close Stay on top of latest health news from Harvard Medical School. Plus, get a FREE copy of the Best Diets for Cognitive Fitness. |

| Introduction | Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Geographical variation of overweight, obesity and related risk factors: Findings from the European Health Examination Survey in Luxembourg, — Beliyaev, Regional Center for Diabetes, Kemerovo, Russian Federation Daria Borodkina Authors Olga Gruzdeva View author publications. WC, proximal thigh circumference and body mass index BMI. This study was supported by a Wonkwang University grant. |

Visceral fat and cardiovascular health -

Eur J Clin Nutr ; Bozorgmanesh M, Hadaegh F, Azizi F. Predictive performances of lipid accumulation product vs. adiposity measures for cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality, 8. Lipids Health Dis ; Gasevic D, Frohlich J, Mancini GJ, Lear SA. Clinical usefulness of lipid ratios to identify men and women with metabolic syndrome: a cross-sectional study.

Kawamoto R, Tabara Y, Kohara K, Miki T, Kusunoki T, Takayama S, et al. Relationships between lipid profiles and metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance and serum high molecular adiponectin in Japanese community-dwelling adults.

Taskinen MR, Barter PJ, Ehnholm C, Sullivan DR, Mann K, Simes J, et al. Ability of traditional lipid ratios and apolipoprotein ratios to predict cardiovascular risk in people with type 2 diabetes.

Tokunaga K, Matsuzawa Y, Ishikawa K, Tarui S. A novel technique for the determination of body fat by computed tomography.

Int J Obes ; Ladeiras-Lopes R, Sampaio F, Bettencourt N, Fontes-Carvalho R, Ferreira N, Leite-Moreira A, et al. The ratio between visceral and subcutaneous abdominal fat assessed by computed tomography is an independent predictor of mortality and cardiac events.

Rev Esp Cardiol Engl Ed ; Higuchi S, Kabeya Y, Kato K. Visceral-to-subcutaneous fat ratio is independently related to small and large cerebrovascular lesions even in healthy subjects. Atherosclerosis ; Kyrou I, Panagiotakos DB, Kouli GM, Georgousopoulou E, Chrysohoou C, Tsigos C, et al.

Lipid accumulation product in relation to year cardiovascular disease incidence in Caucasian adults: the ATTICA study. Dai H, Wang W, Chen R, Chen Z, Lu Y, Yuan H. Lipid accumulation product is a powerful tool to predict non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Chinese adults.

Nutr Metab Lond ; Taverna MJ, Martínez-Larrad MT, Frechtel GD, Serrano-Ríos M. Lipid accumulation product: a powerful marker of metabolic syndrome in healthy population.

Eur J Endocrinol ; Stein E, Kushner H, Gidding S, Falkner B. Plasma lipid concentrations in nondiabetic African American adults: associations with insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome. Metabolism ; Karelis AD, Pasternyk SM, Messier L, St-Pierre DH, Lavoie JM, Garrel D, et al.

Relationship between insulin sensitivity and the triglyceride-HDL-C ratio in overweight and obese postmenopausal women: a MONET study. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab ; McLaughlin T, Reaven G, Abbasi F, Lamendola C, Saad M, Waters D, et al.

Is there a simple way to identify insulin-resistant individuals at increased risk of cardiovascular disease?. Am J Cardiol ; Gasevic D, Frohlich J, Mancini GB, Lear SA. The association between triglyceride to high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and insulin resistance in a multiethnic primary prevention cohort.

Pinho CP, Diniz AD, Arruda IK, Leite AP, Petribu MM, Rodrigues IG. Waist circumference measurement sites and their association with visceral and subcutaneous fat and cardiometabolic abnormalities.

Arch Endocrinol Metab ; Pouliot MC, Després JP, Lemieux S, Moorjani S, Bouchard C, Tremblay A, et al. Waist circumference and abdominal sagittal diameter: best simple anthropometric indexes of abdominal visceral adipose tissue accumulation and related cardiovascular risk in men and women.

Rankinen T, Kim SY, Pérusse L, Després JP, Bouchard C. The prediction of abdominal visceral fat level from body composition and anthropometry: ROC analysis.

Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord ; Philipsen A, Jørgensen ME, Vistisen D, Sandbaek A, Almdal TP, Christiansen JS, et al. Associations between ultrasound measures of abdominal fat distribution and indices of glucose metabolism in a population at high risk of type 2 diabetes: the ADDITION-PRO study.

PLoS One ;e Jørgensen ME, Borch-Johnsen K, Stolk R, Bjerregaard P. Fat distribution and glucose intolerance among Greenland Inuit. An Author Correction to this article was published on 25 August Visceral adiposity is a major risk factor of cardiometabolic diseases.

Visceral adipose tissue VAT is usually measured with expensive imaging techniques which present financial and practical challenges to population-based studies. We assessed whether cardiometabolic conditions were associated with VAT by using a new and easily measurable anthropometric index previously published and validated.

Data participants came from the European Health Examination Survey in Luxembourg — Logistic regressions were used to study associations between VAT and cardiometabolic conditions.

We observed an increased risk of all conditions associated with VAT. We observed higher odds in women than in men for all outcomes with the exception of hypertension. Future studies should investigate the impact of VAT changes on cardiometabolic health and the use of anthropometrically predicted VAT as an accurate outcome when no biomedical imaging is available.

Over the past 20 years there has been a significant global increase in the prevalence of cardiovascular CVD and metabolic conditions such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia and metabolic syndrome 1 , 2 , 3 , 4.

Despite downward trends in mortality rates due to CVD in high-income countries over the last decades, new evidence suggests a possible plateau in CVD mortality in recent years 5. An excess of visceral fat is linked to chronic diseases such as metabolic and cardiovascular conditions emphasizing the strong association between cardiometabolic health and excess of ectopic fat 8.

Adipose tissue is a complex organ with different roles on energy metabolism, endocrine function and inflammation 9 , A malfunction produced by an excess of adipose tissue is associated with metabolic disorders In particular, an excess of ectopic fat, located in the abdominal cavity surrounding the organs, also known as visceral adipose tissue VAT , is considered a major risk factor for metabolic and cardiovascular diseases, independently of general adiposity 9 , VAT can be accurately measured through biomedical imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging MRI and computed tomography-scan CT-Scan However, these techniques are expensive, limited to specialised medical use and show high exposures to radiation e.

CT-Scan 13 , thus being ineffective for population-based studies. Due to those limitations, simple anthropometric measurement e. waist circumference WC , waist-to-hip circumference ratio are used for the indirect assessment of visceral adiposity in both clinical and population-based studies 14 , 15 , Nevertheless, these measurements have the major limitation of not being able to differentiate between VAT and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue SAAT.

Recently, Samouda et al. suggested a more accurate anthropometric prediction of VAT by subtracting the most correlated anthropometric measurement with SAAT from an abdominal anthropometric measurement highly correlated with total abdominal adipose tissue and the most possible correlated with VAT Using this equation, VAT can be readily predicted by combining a small number of easy to measure anthropometric features e.

WC, proximal thigh circumference and body mass index BMI. The anthropometric predictive models of VAT developed by Samouda et al. in , were validated by Brown et al. in and They observed that compared to BMI and WC, predicted models of VAT were the most accurate predictors of cardiometabolic conditions as well as all-cause and cause-specific mortality e.

CVD, cancer in Europid descendants from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, — NHANES III , when biomedical imaging data are not available or feasible 18 , Despite having information on the health situation, up-to-date and exhaustive characterizations of the cardiometabolic health are still missing for the Luxembourgish population, particularly in regards to specific risk factors such as VAT accumulation.

The present study aims to assess whether anthropometrically predicted visceral adipose tissue was associated with hypertension, prediabetes and diabetes, as well as hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia, after adjusting for socio-demographic and behavioural characteristics in a population-based study.

Differences were observed between men and women. Men were more likely to have higher BMI, WC, and anthropometrically predicted VAT while women had higher thigh circumference. Men were more likely to have higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides and fasting plasma glucose levels.

Men had almost twice as much hypertension Women smoked and consumed alcoholic drinks less than men. The proportion of hypertension, combined prediabetes and diabetes, hypertriglyceridemia and metabolic syndrome increased with VAT quartiles in both men and women Table 1. The largest prevalence gradient was observed for metabolic syndrome in both men from 1.

The proportion of hypercholesterolemia increased with VAT in both men and women. We observed that median values of WC and thigh circumference increased with VAT, but when we visualized VAT for similar WC values Supplementary Figure S1 , we observed that thigh circumference decreased for both men and women.

Similar results were observed in the prevalence of cardiometabolic conditions by quartiles of WC Supplementary Table S2. Results from logistic regression analysis examining the association between anthropometrically predicted VAT and cardiometabolic conditions are presented in Table 2.

We observed an increase in the odds of all metabolic and cardiovascular conditions associated with VAT in both men and women.

The strength of the association was reduced but remained statistically significant after adjusting for socioeconomic status education and employment status model 1 , and lifestyle model 2.

For women, the values were 1. Nevertheless, women observed a strongest association for combined prediabetes and diabetes 7.

The present study highlighted an increase of all metabolic and cardiovascular conditions associated with anthropometrically predicted VAT in adults aged 25— The association observed was independent of socioeconomic status and lifestyles.

Our findings confirm that VAT is a major independent predictor risk factor of cardiometabolic risk as observed in previous epidemiological studies This can be explained by the high metabolic activity of VAT and its pro-inflammatory activity production of cytokines with inflammatory effects and blocking of those anti-inflammatory 23 , Moreover, compared to other fat deposits, VAT has larger and dysfunctional adipocytes, which are less insulin sensitive and with increased lipolytic activity.

As the adipocytes grow, they accumulate triglycerides, becoming leptin resistant and promoting the synthesis and release of free fatty acids We observed that both WC and thigh circumference increased with VAT, but as previously reported, when WC and age were constant thigh circumference decreased with VAT for both men and women This is in line with previous evidence showing that VAT is the major risk factor of cardiometabolic morbidity and premature mortality, while lower-body fat mas plays a protective role and should be maintained when reducing VAT We observed sex differences in cardiometabolic conditions with men having a higher prevalence of all conditions compared to women, in line with previous evidence among middle-aged adults 27 , Hypertension, combined diabetes and prediabetes and hypertriglyceridemia prevalence were almost twice as high in men compared to women.

Metabolic syndrome was 1. Closely related to these results are differences observed in WC and VAT being both higher in men compared to women as well as certain risk behaviours and socioeconomic differences such as lower consumption of alcohol and cigarettes and lower socioeconomic status in women compared to men.

Sex differences on VAT are expected, since men are characterized by having a greater concentration of fat in the abdominal area compared to women that usually concentrates in the thighs and hip gluteo-femoral pattern As in other high-income countries, in Luxembourg CVD is the leading cause of death Results from the present study show that compared to a previous study conducted in in Luxembourg, no reduction in cardiometabolic conditions has been observed over the last decade 32 and even an increase has been noted in certain conditions such as diabetes or metabolic syndrome This could explain why cardiovascular diseases remained the main cause of mortality in Luxembourg in These results provide compelling evidence on the current burden of cardiovascular and metabolic conditions in Luxembourg in both men and women, and the need for public health initiatives to alleviate the societal impact of these highly prevalent disease conditions.

Moreover, VAT management should be considered as a privilege area of study to tackle metabolic and cardiovascular health issues. As reported in other studies 34 , 35 , we observed that cardiometabolic conditions were more prevalent among individuals with poor nutritional status, smoking, consuming alcohol, and with sedentary habits.

As observed by Shi et al. At present, there is no specific treatment to reduce VAT without also reducing lower-body fat mass. Studies also observed an effect of socioeconomic conditions, with those with lower socioeconomic status being at higher risk of developing cardiometabolic diseases 38 , 39 , Both lifestyle and socioeconomic characteristics explained in part, but not completely, the association between VAT and cardiometabolic conditions, as we observed that the association remained statistically significant even after adjusting for those factors.

Although there is evidence showing that the socioeconomic effect could be mediated by health behaviours e. smoking 35 , we observed two independent effects model 1 and model 2. Results of this study must be interpreted with caution, taking into account the following limitations.

The design of the present study was cross-sectional, hence no temporal relationship or causality can be inferred. The participation rate was rather low yet still representative of the target population VAT was measured indirectly.

Instead of using biomedical imaging techniques e. MRI, CT-Scan , we estimated VAT with anthropometric measurements. Nevertheless, the predictive anthropometric models of VAT used in the present study were previously developed and validated as the most accurate predictor of biological cardiometabolic risk factors, all-cause and cause-specific mortality in Europid descendants, when biomedical imaging data are not available 17 , 18 , Results from these studies observed a high correlation of VAT assessed by imaging techniques with anthropometric VAT models, whereas other studies observed that WC was higher correlated with SAT and fat mass than with VAT Finally, we did not have information on other potential biomarkers of cardiometabolic risk such as markers of inflammation.

In summary, anthropometrically predicted VAT was associated in the present work with all metabolic and cardiovascular conditions in both men and women even after adjusting for socio-demographic and behavioural characteristics.

This reinforces the role played by VAT as a major independent risk factor for cardiometabolic health. Likewise, prospective and intervention studies should place greater focus on the impact of changes in VAT on cardiometabolic health.

Data for the present study came from EHES-LUX, a cross-sectional population based survey done in — The study was performed following a one-stage sampling procedure stratified by age, sex, and district of residence. Residents in Luxembourg aged 25—64 years old were invited randomly to participate in the survey with the exception of those individuals living in institutions such as hospitals, nursing homes or prisons.

A total of individuals participated in the study and signed an informed consent 20 , The survey consisted in 3 sections: a health questionnaire, a medical examination and the collection of biological samples. The analysis of biological samples was performed in a National certified laboratory.

Out of all participants, 21 were pregnant women excluded from the present analysis and underwent biological analysis. A total of individuals had complete information in the three health sections of the survey While objective measures of VAT e.

CT-Scan, MRI are not covered by EHES-LUX, the survey does dispose of accurate and complete set of anthropometric measurements. In the present study we excluded 5 individuals with values of visceral adipose tissue inferior or equal to zero.

One individual did not have a measure of height and thus VAT was not possible to calculate. The final sample size of the present study was participants.

The study was approved by the National Research Ethics Committee CNER, No. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. In this paper, we use the term hypercholesterolemia in reference to total cholesterol.

Metabolic Syndrome was defined following the International Diabetes Federation Weight and height, together with waist, hip and thigh circumferences were measured by trained nurses following Lohman recommendations The equations used to estimate VAT are based on the strong correlation observed between thigh circumference and subcutaneous fat, as assessed by CT-Scan.

The anthropometric VAT model assumed that by subtracting the most correlated anthropometric measurement with SATT from the most correlated anthropometric measurement with total abdominal and VAT as assessed by CT-Scan WC , we can obtain the most accurate prediction of VAT by anthropometry.

Multiple linear regressions with an empirical selection of the variables were performed and validated. Model variances, collinearity, and errors e. Bland and Altman plots representation were assessed.

Sensitivity and specificity of the anthropometric models for the diagnosis of visceral adiposity excess in a clinical setting, along with the positive and negative predictive value of the models for predicting a cut-off of cm2, were also assessed. Models were validated in a second sample of participants 77 women, BMI range: Models were further validated as predictors of cardiometabolic conditions, cancer and early death in Based on the literature review we selected a list of potential covariates 27 , 34 , Demographic characteristics included age and sex men and women.

For both alcohol and physical activity, we used validated questionnaires with standardized questions for European populations from the European Health Interview Survey EHIS. Socioeconomic characteristics included education tertiary education vs secondary and primary , and job status employed vs not employed.

We test normality with the Kolmogorov—Smirnov test. Medians were used for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. To analyse associations between cardiometabolic outcomes e.

hypertension, prediabetes and diabetes and total cholesterol and covariates, we used a Pearson's chi-squared test for probabilities related to frequencies or Wilcoxon—Mann—Whitney U two-sample test for probabilities related to medians to compare characteristics between men and women.

We used non parametric test because data was not normally distributed. Distributions of cardiometabolic conditions across VAT quartiles were measured with the Cochran-Armitage P-trend test for categorical variables and Jonckheere-Terpstra test for continuous variables.

We performed multivariable logistic regression analyses to study the association between VAT quartiles and cardiometabolic outcomes in unadjusted Model 1 and adjusted models for education and employment status Model 2 , and lifestyle e. smoking, alcohol consumption and physical activity and socioeconomic conditions Model 3.

All analyses were stratified by sex, given the well-known differences in visceral adiposity distribution and cardiometabolic disease prevalence between women and men Anderson PJ, Chan JC, Chan YL, Tomlinson B, Young RP, Lee ZS, et al.

Visceral fat and cardiovascular risk factors in Chinese NIDDM patients. Diabetes Care. Després JP. Body fat distribution and risk of cardiovascular disease an update.

Sironi AM, Petz R, De Marchi D, Buzzigoli E, Ciociaro D, Positano V, et al. Impact of increased visceral and cardiac fat on cardiometabolic risk and disease. Diabet Med.

St St-Pierre J, Lemieux I, Vohl MC, Perron P, Tremblay G, Després JP, et al. Contribution of abdominal obesity and hypertriglyceridemia to impaired fasting glucose and coronary artery disease.

Am J Cardiol. Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Ventura HO. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: risk factor, paradox, and impact of weight loss. J Am Coll Cardiol. Klöting N, Blüher M.

Adipocyte dysfunction, inflammation and metabolic syndrome. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. Tarui S, Tokunaga K, Fujioka S, Matsuzawa Y. Visceral fat obesity: anthropological and pathophysiological aspects.

Int J Obes. PubMed Google Scholar. Capeau J. Insulin resistance and steatosis in humans. Diabetes Metab. Kotronen A, Yki-Jarvinen H. Fatty liver: a novel component of the metabolic syndrome. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. Abdulkadirova FR, Ametov AS, Doskina EV, Pokrovskaya RA.

The role of the lipotoxicity in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity. Obes Metab. Sung KC, Wild SH, Kwag HJ, Byrne CD.

Fatty liver, insulin resistance, and features of metabolic syndrome: relationships with coronary artery calcium in 10, people. Gastaldelli A, Cusi K, Pettiti M, Hardies J, Miyazaki Y, Berria R, et al.

Targher G, Zoppini G, Day CP. Risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with chronic liver disease. author reply —4. Kozakova M, Palombo C, Eng MP, Dekker J, Flyvbjerg A, Mitrakou A, et al. Fatty liver index, gamma-glutamyltransferase, and early carotid plaques. Bonapace S, Perseghin G, Molon G, Canali G, Bertolini L, Zoppini G, et al.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes. Assy N, Djibre A, Farah R, Grosovski M, Marmor A. Presence of coronary plaques in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Pezeshkian M, Noori M, Najjarpour-Jabbari H, Abolfathi A, Darabi M, Darabi M, et al. Fatty acid composition of epicardial and subcutaneous human adipose tissue. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. Iacobellis G, Corradi D, Sharma AM. Epicardial adipose tissue: anatomic, biomolecular and clinical relationships with the heart.

Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. Löhn M, Dubrovska G, Lauterbach B, Luft FC, Gollasch M, Sharma AM. Periadventitial fat releases a vascular relaxing factor. FASEB J. Yamaguchi Y, Cavallero S, Patterson M, Shen H, Xu J, Kumar SR, et al. Adipogenesis and epicardial adipose tissue: a novel fate of the epicardium induced by mesenchymal transformation and PPARγ activation.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Manzella D, Barbieri M, Rizzo MR, Ragno E, Passariello N, Gambardella A, et al. Role of free fatty acids on cardiac autonomic nervous system in noninsulin-dependent diabetic patients: effects of metabolic control.

J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Mahabadi AA, Massaro JM, Rosito GA, Levy D, Murabito JM, Wolf PA, et al. Association of pericardial fat, intrathoracic fat, and visceral abdominal fat with cardiovascular disease burden: the Framingham heart study.

Eur Heart J. Corradi D, Maestri R, Callegari S, Pastori P, Goldoni M, Luong TV, et al. The ventricular epicardial fat is related to the myocardial mass in normal, ischemic and hypertrophic hearts. Cardiovasc Pathol. Eroglu S, Sade LE, Yildirir A, Bal U, Ozbicer S, Ozgul AS, et al.

Epicardial adipose tissue thickness by echocardiography is a marker for the presence and severity of coronary artery disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. Wang CP, Hsu HL, Hung WC, Yu TH, Chen YH, Chiu CA, et al.

Increased epicardial adipose tissue EAT volume in type 2 diabetes mellitus and association with metabolic syndrome and severity of coronary atherosclerosis. Clin Endocrinol. Romantsova TI, Ovsyannikovna AV.

Perivascular adipose tissue: role in the pathogenesis of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular pathology. Frontini A, Rousset S, Cassard-Doulcier AM, Zingaretti C, Ricquier D, Cinti S.

Thymus uncoupling protein 1 is exclusive to typical brown adipocytes and is not found in thymocytes. J Histochem Cytochem. Sacks HS, Fain JN, Holman B, Cheema P, Chary A, Parks F, et al. Uncoupling protein-1 and related messenger ribonucleic acids in human epicardial and other adipose tissues: epicardial fat functioning as brown fat.

Chatterjee TK, Stoll LL, Denning GM, Harrelson A, Blomkalns AL, Idelman G, et al. Proinflammatory phenotype of perivascular adipocytes: influence of high-fat feeding. Circ Res.

Li T, Liu X, Ni L, Wang Z, Wang W, Shi T, et al. Perivascular adipose tissue alleviates inflammatory factors and stenosis in diabetic blood vessels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. Schlett CL, Massaro JM, Lehman SJ, Bamberg F, O'Donnell CJ, Fox CS, et al. Novel measurements of periaortic adipose tissue in comparison to anthropometric measures of obesity, and abdominal adipose tissue.

Rittig K, Staib K, Machann J, Böttcher M, Peter A, Schick F, et al. Perivascular fatty tissue at the brachial artery is linked to insulin resistance but not to local endothelial dysfunction.

Lehman SJ, Massaro JM, Schlett CL, O'Donnell CJ, Hoffmann U, Fox CS. Peri-aortic fat, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and aortic calcification: the Framingham heart study.

Pfeifer A, Hoffmann LS. Brown, beige, and white: the new color code of fat and its pharmacological implications. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. Rosenwald M, Perdikari A, Rülicke T, Wolfrum C.

Bi-directional interconversion of brite and white adipocytes. Nat Cell Biol. Omar A, Chatterjee TK, Tang YL, Hui DY, Weintraub NL.

Proinflammatory phenotype of perivascular adipocytes. Zhang H, Park Y, Wu J, Chen X, Lee S, Yang J, et al. Role of TNF-alpha in vascular dysfunction. Clin Sci Lond. Download references. Federal State Budgetary Institution, Research Institute for Complex Issues of Cardiovascular Diseases, Kemerovo, Russian Federation.

Federal State Budget Educational Institution of Higher Education, Kemerovo State Medical University of the Ministry of Healthcare of the Russian Federation, Kemerovo, Russian Federation. Autonomous Public Healthcare Institution of the Kemrovo Region, Kemerovo Regional Clinical Hospital named after S.