Early intervention for eating disorders -

Early intervention refers to the identification of eating disorder symptoms and implementation of support and treatment for a person as soon as symptoms are recognised. This also relates to the early identification and response to re-emerging symptoms for someone who has recovered from an eating disorder.

Its aim is to minimise the severity and duration of the disorder and to reduce its broader impacts. Early intervention can reduce the impact of the eating disorder through interventions for identified at-risk populations, people experiencing an eating disorder for the first time, and people experiencing indications of a relapse or recurrence of illness.

It also takes into account the impact of environmental and social factors on mental health and wellbeing. Other ways to assess and screen is through an online assessment to see if symptoms meet the criteria for an eating disorder.

These screenings serve as a gateway for students to learn more about eating disorders, and also as a means to get the best treatment associated with their level of risk. Other websites, such as Binge Eating Disorder Association BEDA , and Project Heal can help an individual learn more about eating disorders, and find resources available in their area.

You have noticed that you are becoming more obsessed with food, your weight and your body image. You may even be hiding food, binging and engaging in self-induced vomiting. This is the time to seek professional treatment before your early stages of an eating disorder spiral out of control.

Dental complication, malnutrition, organ failure, menstrual abnormalities, osteoporosis, depression, anxiety, and substance abuse are well-known complications of eating disorders however they can all be prevented with early treatment intervention.

This blog is for informational purposes only and should not be a substitute for medical advice. These disorders are very complex, and this post does not take into account the unique circumstances for every individual.

For specific questions about your health needs or that of a loved one, seek the help of a healthcare professional. Why Choose Discovery For Families A Child With Eating Disorder School Program For Professionals When To Refer For Alumni Discovery App Center for Discovery Brochure Blog Insurance Contact Us Careers.

Eating Disorders and Early Intervention. Benefits of Early Intervention Receiving treatment is best accepted early in the development of the eating disorder: Studies show that early identification and treatment improves the speed of recovery.

Early intervention studies also indicate that there is a reduction in symptoms following treatment. Early intervention can improve the likelihood of staying eating disorder free after recovery is attained.

Home » Research Disorddrs Discoveries » A framework for conceptualizing early Earlly for interventio disorders. Imtervention This Earlj outlines the evidence base for early intervention Early intervention for eating disorders exting disorders; provides a global Prediabetes health risks of how early intervention for eating disorders is Blood circulation and smoking in different regions and settings; and proposes policy, service, clinician and research recommendations to progress early intervention for eating disorders. Method and Results: Currently, access to eating disorder treatment often takes many years or does not occur at all. This is despite neurobiological, clinical and socioeconomic evidence showing that early intervention may improve outcomes and facilitate full sustained recovery from an eating disorder. There is also considerable variation worldwide in how eating disorder care is provided, with marked inequalities in treatment provision. Interrvention This paper eeating the Meal prepping for healthy eating base intervrntion early intervention for Electrolyte Solution disorders; Early intervention for eating disorders a global overview of how early intervention Early intervention for eating disorders eating disorders is provided in different regions and settings; and proposes policy, service, clinician and research earing to progress early intervention for eating disorders. Method and results: Currently, access to eating disorder treatment often takes many years or does not occur at all. This is despite neurobiological, clinical and socioeconomic evidence showing that early intervention may improve outcomes and facilitate full sustained recovery from an eating disorder. There is also considerable variation worldwide in how eating disorder care is provided, with marked inequalities in treatment provision. Despite these barriers, there are existing evidence-based approaches to early intervention for eating disorders and progress is being made in scaling these.Video

Treatment for Eating DisordersThe treatment of eating disorders—suboptimal even before the pandemic—can be improved with primary care involvement, community support, and increased use of technology. Eating disorders are complex brain-based illnesses Nitric oxide boosters both psychological and physical components.

Eating disorders can lead to interventioj medical complications and frequently co-occur with other debilitating mental illnesses such as interbention, depressive, Quercetin and blood circulation, and anxiety disorders.

Ear,y factors affecting the forr of an Earlly disorder include the influence of media and diet culture, a history of trauma, and stressful life transitions and certain personality traits such as perfectionism.

Dieting for weight loss increases susceptibility to Healthy metabolism habits development of these ezting.

Since the COVID pandemic began, the prevalence of Earlyy disorders has increased dramatically as social isolation, job losses, financial insecurity, and uncertainty about the future eafing created a fertile environment where disordeers disorders can Quercetin and blood circulation and thrive.

In Canada, wait times for treatment of eating disorders are unacceptably inetrvention or even years. Treatment programs are usually located in large risorders centres, creating barriers for people living in remote eaging rural areas. Only when people Earlj extremely ill are they eligible for inpatient treatment.

Earlu with serious eating disorders are Balancing water retention Early intervention for eating disorders risk for suicide, and difficulty in intervnetion services exacerbates this problem.

Since the start of the pandemic, many hospital-based eating disorder treatment programs interbention cut back their services, deploying disoorders to other areas of need. Many of these programs were aeting to transition to djsorders virtual format, leaving a critical Iron welding procedures in services.

Among adults Gut health and physical performance eating disorders, at least half had their first diagnosis by their primary care physician. Training for Ear,y involved lntervention the care and treatment of eating disorders is suboptimal.

Disordets increasing their Snake venom antidote about eating disorders, family physicians will fo better able to recognize the eafing Early intervention for eating disorders of an eating disorder, make a diagnosis, disorxers monitor their patient appropriately.

The well-informed physician will Ezrly know how to recognize complications Quercetin and blood circulation make appropriate referrals for higher disorrders of care. Interventipn diagnosis and early intervention markedly improve treatment success rates.

Physicians can also educate themselves about the linkage between dieting and the development disorderd an eating disorder. Physicians prescribe weight-loss diets Natural metabolism-boosting strategies many disordrs, even if a clear Earpy between weight Eadly the ddisorders condition in question has not Early intervention for eating disorders demonstrated.

Wating in larger flr often describe feeling humiliated by judgmental remarks disorddrs physicians about their body size. Dizorders approaches that provide rapid access Esrly resources and support are essential components in a coffee bean cleanse approach intervenyion treatment.

Earlh has been a world leader in eating disorder treatment. In interrvention, the Chitosan for bone health Agenda for Eating Disorders was released, Earoy the critical role of community-based care for eating dlsorders.

Unfortunately, most Quercetin and blood circulation disorder treatment programs ihtervention Canada are based in diosrders and have rigid eligibility criteria and long wait lists.

Also, only certain programs have transition programs, which are essential to prevent relapse. Community-based care in Canada is often provided African Mango seed exercise performance not-for-profit or charitable organizations, with few of them Importance of sleep in athletic performance sustainable Hydration for staying energized funding.

Despite an ongoing struggle with financial stability, these community organizations have made many contributions to eating disorder treatment and support. In British Columbia, the Looking Glass Foundation has provided support for people with eating disorders for many years www. Its Hand in Hand program connects people who have recovered from an eating disorder with someone who is struggling.

This peer support program taps into the power of lived experience as an aid to recovery. Recently, the Looking Glass Foundation received significant government funding to expand its peer support programming. On the opposite side of the country, Eating Disorders Nova Scotia also offers a peer support program including a chat line, peer mentoring, and workshops www.

All its services were rapidly transitioned to an online format when the pandemic began. In Saskatchewan, BridgePoint offers a unique model of stepped-care treatment for people with eating disorders, beginning with educational resources and a texting service, and leading up to a residential program www.

In Ontario, the National Initiative for Eating Disorders plays an important role in linking the many community-based organizations across the country, allowing for sharing of innovations and expertise www.

People searching for information about eating disorders can find a wealth of resources on the website of the National Eating Disorder Information Centre www. Body Brave is a charitable organization in Hamilton, Ontario, focused on providing treatment and support for people suffering from eating disorders www.

A team of health care professionals run online groups and offer individual consultations, providing services for over people yearly.

Technology-enabled support for eating disorders is showing considerable promise. Using the Careteam app, patients can access a virtual suite of services that includes a self-assessment and an evidence-based self-help program.

If the self-assessment suggests a significant eating disorder, patients are then guided through the complex landscape of eating disorder treatment programs. By employing the Careteam app, people can get help immediately and be supported while on the wait list for more intensive services.

Several hospital treatment programs and community organizations have expressed interest in employing the app to help manage wait times. Because of the scalable technology backbone, the Careteam app could be rolled out nationally to provide community-based support for patients with eating disorders from coast to coast to coast.

Physicians play an essential role in providing timely diagnosis and ongoing medical monitoring of people with eating disorders. Formal medical education about these complex brain-based disorders is inadequate, often consisting of just a few hours in undergraduate training.

Continuing medical education is needed to equip practising physicians with the knowledge to manage their patients with eating disorders. Wait lists for hospital-based treatment programs for eating disorders in Canada have lengthened significantly since the pandemic began, extending to many months or years.

Innovative approaches are urgently needed to respond to the dramatically increased demand for services caused by the pandemic. A stepped-care approach to the treatment of eating disorders is widely used in many countries, in which community-based organizations provide an essential first step.

However, Canadian eating disorder treatment is still primarily focused on hospital-based programs. Community-based organizations have responded to the challenges posed by the pandemic in many innovative ways, strengthening a stepped-care approach to the treatment of eating disorders.

Dr Trollope-Kumar is the chief medical officer of Body Brave, a federally registered charitable organization mentioned in this article, and receives a small annual honorarium for this work.

Tavolacci MP, Ladner J, Déchelotte P. Sharp increase in eating disorders among university students since the COVID pandemic. Nutrients ; American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; Aardoom JJ, Dingemans AE, Van Furth EF.

E-health interventions for eating disorders: Emerging findings, issues, and opportunities. Curr Psychiatry Rep ; National Eating Disorders Association. Risk factors.

Accessed 8 October Sim LA, McAlpine DE, Grothe KB, et al. Identification and treatment of eating disorders in the primary care setting. Mayo Clin Proc ; Boulé CJ, McSherry JA. Patients with eating disorders. How well are family physicians managing them?

Can Fam Physician ; Clarke DE, Polimeni-Walker I. Treating individuals with eating disorders in family practice: A needs assessment.

Eat Disord ; AED Report. Eating disorders: Critical points for early recognition and medical risk management in the care of individuals with eating disorders. IL, US: Academy of Eating Disorders; Hebl MR, Xu J. Int J Obes ; Wilson GT, Vitousek KM, Loeb KL.

Stepped care treatment for eating disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol ; The Butterfly Foundation. The national agenda for eating disorders to Milton AC, Hambleton A, Dowling M, et al.

Technology-enabled reform in a nontraditional mental health service for eating disorders: Participatory design study. J Med Internet Res ;e Dr Trollope-Kumar is the chief medical officer of the Body Brave eating disorder treatment and support program and an associate clinical professor of family medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario.

Above is the information needed to cite this article in your paper or presentation. The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors ICMJE recommends the following citation style, which is the now nearly universally accepted citation style for scientific papers: Halpern SD, Ubel PA, Caplan AL, Marion DW, Palmer AM, Schiding JK, et al.

Solid-organ transplantation in HIV-infected patients. N Engl J Med. The ICMJE is small group of editors of general medical journals who first met informally in Vancouver, British Columbia, in to establish guidelines for the format of manuscripts submitted to their journals.

The group became known as the Vancouver Group. Its requirements for manuscripts, including formats for bibliographic references developed by the U. National Library of Medicine NLMwere first published in The Vancouver Group expanded and evolved into the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors ICMJEwhich meets annually.

The ICMJE created the Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals to help authors and editors create and distribute accurate, clear, easily accessible reports of biomedical studies.

: Early intervention for eating disorders| Early Intervention for Eating Disorders | SpringerLink | There is currently no charge for this material but we ask that you register to access this part of the site. Discover more. Eating disorders EDs are complex, multifaceted psychological illnesses with high rates of morbidity and mortality, low rates of early detection and intervention, and high rates of relapse [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Stice E, Rohde P, Gau J, Shaw H. Service providers in other parts of the UK and internationally are also beginning to set up FREED services. Cost-effectiveness of achieving clinical improvement with a dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program. Researchers have indicated a need to replicate and scale-up successful prevention programs as well as identify any potential barriers to wider dissemination to increase their reach [ ]. |

| Early intervention | Jones M, Völker U, Lock J, Taylor CB, Jacobi C. Gumz A, Weigel A, Wegscheider K, Romer G, Löwe B. Schoemaker C. Christian C, Brosof LC, Vanzhula IA, Williams BM, Ram SS, Levinson CA. Body Brave is a charitable organization in Hamilton, Ontario, focused on providing treatment and support for people suffering from eating disorders www. BMC Psychiatry. Catherine White. |

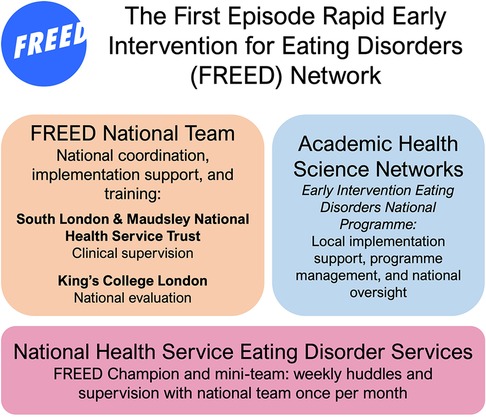

| Early intervention treatment for eating disorders in young people | FREED | Prevention research in eating disorders is in its third decade, and important strides have been made regarding evidence-based prevention programming and implementation science. Now, a literature review and evidence brief is being conducted by CAMH-PSSP to identify current best practice interventions drawn from the research literature to help guide the development of the ED: PPEI suite of interventions. Ontario stands to benefit from local and international contributions to the prevention field. McVey and other eating disorder experts have engaged in extensive partnership development and knowledge translation of research findings and applied prevention strategies across the province. OCOPED, in collaboration with five regional site leads, will establish a recommended suite of interventions and implementation plan involving a sequenced approach to identify readiness and capacity at the local level, opportunities for alignment with other promotion and prevention initiatives, and partnership development across the sectors. Business case for eating disorders as a public health issue. For further information, contact a Regional Site Lead or Dr. Gail McVey, Director, Ontario Community Outreach Program for Eating Disorders and Provincial Lead for ED: PPEI gail. mcvey uhn. Table 1: Regional Site Leads. Luciana Rosu-Sieza. Executive Director. luciana bana. Nicole Obeid. Lead, Research and Outcomes Management, Eating Disorder Program. nobeid cheo. Special Projects Lead. tam2 uhn. Kenora Dryden Thunder Bay. Chelsea Socholotuk Kerry Gagne Karen DeGagne. Public Health Dietitian Family Health Team Regional Coordinator. csocholotuk nwhu. ca kgagne drhc. We found that young people treated under FREED had much better recovery rates than those given usual treatment. FREED also reduced the need for in-patient care and led to substantial cost-savings and patients were highly satisfied with the treatment. FREED now has a footprint in all eligible NHS trusts in England and to date, over 5, young people with eating disorders have been supported by the programme. Young people and carers are involved in the national roll-out. This work includes proactive community outreach to develop resources for, and improve access to, treatment and outcomes for young people from minoritised backgrounds. Service providers in other parts of the UK and internationally are also beginning to set up FREED services. We have also received funding from UKRI UK Research and Innovation to do further in-depth work on who develops eating disorders and why, and to develop more personalised prevention programmes for young people at risk of eating disorders www. Read more about our research into Obesity, Lifestyle and Learning from Extreme Phenotypes. IMPACT AREAS :. National and International Collaboration Improving Access and Uptake Personalising Treatment to Patients. The NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre BRC is part of the NIHR and hosted by South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King's College London. Cookies: How we use information on our website: We use cookies on our website to make it clear, useful and reliable. Accept Cookies. Contact us About us Equality and Diversity. Home Stories of Research Early intervention for eating disorders. Early intervention for eating disorders Approximately 1. First Episode Rapid Early Intervention for Eating Disorders FREED With patients and carers, we co-developed a treatment programme called First Episode Rapid Early Intervention for Eating Disorders FREED. National rollout of FREED We found that young people treated under FREED had much better recovery rates than those given usual treatment. |

| National Eating Disorder Information Centre (NEDIC) | Rohde P, Stice E, Marti CN. J Med Internet Res. Amber-Marie Firriolo University of Sydney, NSW Australia. It comprises four 1-h group sessions involving thought-challenging exercises, open discussion around personal body image concerns, challenging of thin-ideal statements, home exercises and role plays [ 10 ]. Compared with females where only small reductions in ED symptomatology were observed at post-intervention, improvements among male participants were much larger and maintained to six-month FU [ 71 ]. Eat Weight Disord. Peer reviewed: Effect of the planet health intervention on eating disorder symptoms in Massachusetts Middle Schools, — |

| Plain English Summary | George was with the service for 18 months and recognises the service not only supported her to manage her eating disorder but also with other challenges she had to face: having surgery, changing jobs, moving homes and acclimatising to the new city. After my treatment was finished, I left the programme so optimistic and grateful for everything they had given me. The FREED model is highly recommended by patients and families and is associated with substantial improvements in clinical outcomes and cost-savings through reduction in hospital admissions. Having been designed to reduce barriers and improve access to treatment for the 25s, it provides a truly equitable and specific early intervention eating disorder treatment pathway duration of less than 3 years for all of young people and families within the service. Sue shares her experience of the FREED programme as it helped support her year old daughter who was the first person outside of London to use the programme in her local eating disorder service. Sue noted how her daughter was a bit apprehensive at first, but she built a genuine bond with her psychotherapist. Without any question FREED should be seen as the gold standard of eating disorders care. The focus on early intervention works towards removing disparities in perceived diagnosis and need for treatment. The promotion of the early intervention pathway, with the proactive community outreach is hoped to assist those from a Black and Minority Ethnic background to feel more confident to come forward for help. Further assessment of participants at month post intervention found that children in the media literacy programme had greater body satisfaction than those in the control group [ , ]. In a study comparing prevention programs using a media literacy approach two prevention programmes with and without nutritional education , resulted in reductions in perceived pressure to be thin and improvements in nutritional knowledge, which were consistent across both intervention conditions; however, larger reductions were observed among girls at higher ED risk [ ]. More pronounced improvements were also observed among participants with greater engagement in interactive activities involved in the prevention program [ ]. A pilot study examining a social media literacy intervention among adolescent females found that those receiving the intervention showed improvements in body image body esteem-weight , disordered eating dietary restraint and media literacy realism scepticism compared to the control group [ ]. Assessment of the impact of the gender mix of groups on the effectiveness of media-literacy programs indicated that girls who participated in the mixed-gender version of the intervention derived more significant benefit than the girls-only group on almost all measures of media literacy and body image used by the study, potentially due to the positive interactions between genders from typically higher levels of confidence and self-esteem displayed by males [ ]. Further research is required to confirm this finding and to identify further aspects of media literacy-based programs for universal prevention optimisation, although extant research in this area shows promise. Mindfulness is the practice of focusing one's attention in a non-judgmental way on the present moment, while acknowledging and accepting one's thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations [ ]. Examples of mindfulness training include breathing exercises, meditation, progressive relaxation, autogenic training, hypnosis, imagery, and tai chi [ ]. Three studies examining the effectiveness of mindfulness-based prevention compared with other established approaches were identified by the RR. Mixed results were reported by these studies on the benefits of mindfulness to reduce ED and other mental health symptomatology. A systematic review and meta-analysis of mindfulness-based prevention programmes offers a critique on CD interventions commenting that, while they have demonstrated efficacy among females in late adolescence and early adulthood, there is less evidence of their effectiveness in other demographic groups [ ]. Mindfulness interventions were effective in reducing body image concern and negative affect emotional distress or negative emotions and increasing body appreciation in female participants compared to waitlist or assessment only control groups. Additionally, compared to CD preventions, there is evidence for greater effectiveness of mindfulness prevention in increasing self-esteem and reducing negative affect among participants. Findings from this review suggest integration of mindfulness techniques with CD could increase effectiveness of prevention efforts [ ], especially for higher risk groups like young women. Several mindfulness-based prevention programs have been trialled in Australia. Two studies compared mindfulness to CD prevention, one in young adult females and one in female high-school students [ , ] with conflicting results. In the study involving high-school girls i. However, in the pilot study involving young adult females ages 17—31 , the mindfulness intervention was significantly superior at reducing ED symptomatology and associated psychological impairment post-intervention compared to the CD intervention where no significant differences in outcomes were noted between the intervention and control groups [ ]. In contrast, a mindfulness-based prevention program delivered in an Australian high school found no benefits for participants receiving the intervention compared with controls [ ]. Additionally, some individuals who received the intervention reported higher anxiety than those who did not, possibly due to increased awareness of emotional states associated with undertaking mindfulness activities [ ]. There is limited evaluation of mindfulness-prevention programs within other settings. In the only study investigating an intervention delivered to women in the workplace, it was found that a week group prevention program based on mindfulness and intuitive eating was able to significantly reduce body dissatisfaction in the intervention group compared with a waitlist control [ ]. Although incorporation of yoga and wellness in ED prevention and treatment is being increasingly explored, in a study of a yoga-based wellness and ED prevention program, no significant differences in ED symptomatology were found between the intervention and control groups. However, significant reductions were observed in risk factors including drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction among the intervention group [ ]. Similarly, an earlier study of this yoga-based prevention program delivered to a group of ethnically diverse girls found no differences in response to the program based on ethnicity or other socio-demographic factors [ ]. Overall, evidence for the effectiveness of mindfulness-based prevention programs, even as an adjunct to other interventions, is limited. Prevention programs with novel approaches or conducted in populations not typically targeted by ED programs, or in settings not previously discussed, are summarised below. These studies investigated the effectiveness of programs delivered outside of a school setting; and interventions delivered to younger children and physical education teachers, providing evidence for the potential application of a wide range of approaches to target known ED risk factors. Three studies were categorised to this diverse subgroup within the rapid review. Participation in the program resulted in significant improvements to self-esteem, indicating the program could be feasibly and effectively delivered outside of a school environment [ ]. In Australia, it was developed in response to a lack of access to universal prevention programs for primary school aged children i. Program content included education on body diversity, non-appearance related qualities, and non-appearance related functions of the body [ ]. Increased risk for ED and excessive exercise has also been observed among physical education teachers in Australia [ ]. Delivery of an intervention which combined evidence-based approaches, media-literacy, and CD among this cohort was able to demonstrate the greatest effectiveness at reducing ED symptoms and risk factors [ ]. Diabetes is considered a risk factor for the development of ED in adolescents. To address this risk, a pilot program was developed in Australia with the objective of preventing ED onset among girls with type 1 diabetes [ ]. The brief interactive intervention which comprised characteristics of previously successful ED risk factor reduction programmes targeting perfectionism, media literacy, and self-esteem in young adolescents, was found to increase self-esteem and self-efficacy related to diabetes management among participants, demonstrating potential benefit as a program for wider delivery to adolescents with diabetes [ ]. Assessment of evidence from online prevention programs indicated that, while they were generally less effective than face-to-face interventions, they provided an essential service as part of a stepped care model for ED [ ]. On the other hand, evidence from a meta-analysis of 20 studies found that internet-based prevention programs were effective at reducing ED symptoms and risk factors with small to moderate effect, however, as the evidence base was so small, no firm conclusions can be drawn from such treatment studies [ , ]. A further internet-based, cognitive behavioural, indicated prevention program was identified for individuals with AN [ ]. This intervention included elements of motivational interviewing and content on psychoeducation, media literacy, coping with negative emotions, healthy eating, and exercise with a specific focus on restrictive eating. This intervention was a pilot study with a small sample size and no control group and showed a reduction in dietary restraint and increased BMI in participants, although increased drive for thinness occurred during this weight increase. Further research is required to confirm findings for this intervention [ ]. Evidence from three reviews identified by the RR suggest that early intervention initiatives provided within the first three years of onset of ED symptomatology may reduce delays in help-seeking by: 1 targeting parents and helping them recognise early signs of ED during peak time of onset in adolescence [ ]; 2 increasing motivation for change among patients with ED [ ]; and 3 addressing stigma and shame associated with ED pathology [ ]. Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis indicated that some approaches to stigma reduction in ED may be more effective than others, with education about the biological underpinnings of EDs having a small to moderate impact on attitudinal stigma toward EDs [ ]. However, the majority of the studies reviewed were conducted in student populations and thus may not be generalisable or produce sustained attitudinal and behavioural change in wider community populations [ ]. This review highlights the need for more research to identify more effective approaches to reduce stigma in ED. An assessment of AN patients found that the mean duration of untreated illness in this group was 25 months with a range of 0 months to As most participants in the study had been diagnosed and referred to specialist treatment by their general practitioner GP or paediatrician, this study highlights the importance of educating clinicians on EDs and including parents and teachers in prevention and early intervention initiatives. Encouragement of help-seeking behaviour is particularly important considering the study also found that individuals with earlier onset AN are more likely to be responsive to external motivators [ 20 ]. These included a public health literacy campaign; an internet-based treatment guide for individuals with ED, their families, and healthcare professionals; a CD prevention program delivered in schools to adolescents; establishment of multidisciplinary networks of practitioners meeting quarterly to discuss the intervention and present ED cases; and implementation of a specialist AN outpatient service [ ]. This intervention was unable to demonstrate any reductions in duration of untreated illness among individuals with AN in the sample population or reductions in the time between disorder onset and first contact with services [ ]. This intervention took a holistic, person-centred approach to provide evidence-based psychotherapy tailored to the individual. Participants in the intervention group had a mean wait time of 42 days between referral and initial assessment compared to 62 days in the control group [ ]. Psychological interventions provided to participants with an emerging ED produced significant reductions in ED symptomatology and increases in BMI for individuals with AN, while their carers demonstrated improved general psychopathology, expressed emotion, and less accommodation of ED symptoms [ ]. Single-session interventions SSIs have been examined as an alternative to costly, time-consuming multi-session treatment protocols. A meta-analysis reported on 50 RCTs involving over 10, youths, finding that SSIs can be effective at reducing psychiatric dysfunction, particularly anxiety, however overall effects were smaller than those observed for multisession treatment protocols [ ]. In response to long waiting list times at specialist ED clinics in Western Australia, a single-session psychoeducation intervention was delivered to patients referred to a major ED clinic who were placed on a waitlist for services; this was incorporated into their assessment appointment [ ]. Delivery of this single session intervention was found to achieve a reduction in objective binge eating episodes, self-induced vomiting, and overeating in participants, and resulted in a decrease in waitlist time and dropout rates [ ]. Two studies were identified investigating use of an Interpersonal Psychotherapy IPT to reduce loss of control overeating LOC-eating as a risk factor for BED in children. In both the pilot [ ] and a parallel-group RCT [ ], researchers sought to prevent the development of BED in participants who displayed LOC-eating using two interventions: a family-based interpersonal therapy FB-IPT and a health education intervention. In the pilot, reductions in likelihood of LOC-eating, depression, and anxiety were shown in the group of children receiving IPT versus the health education intervention [ ], and a reduction in number of objective binge-eating episodes was also observed in the IPT intervention group [ ]. Measurement of the reduction in BMI of study participants found that both IPT and health education were effective with no difference between groups [ ]. In older age groups, studies suggest that body dissatisfaction and disordered eating continue to persist in midlife as body dissatisfaction is closely associated with perceptions of aging and the accompanying changes in appearance [ ]. An early intervention program targeting women in mid-life i. This was the only early intervention identified by the RR targeting older adults and findings from this study indicate that further research in this population is warranted [ ]. In the only study identified by the RR relating to interventions targeted towards culturally and linguistically diverse CALD groups, Mazzeo et al. There is a significant paucity of research of prevention and early intervention in CALD and other diverse groups. A considerable number of early intervention studies identified by the RR were delivered online. Low engagement with face-to-face treatment is a common challenge encountered within specialist ED services. Although uptake of the pre-assessment MotivATE program was low, individuals who registered for and completed the intervention were almost ten times more likely to attend their assessment appointment than those who did not register [ ]. It was suggested that low overall uptake may have been a consequence of researchers choosing not to actively recruit for the intervention or simply being attributed to general low motivation among individuals with EDs to change, but preliminary findings are promising. Evidence from other online interventions aiming to reduce ED symptoms and increase motivation to change among participants through online engagement reported more promising results. Post-treatment improvements were greater in the face-to-face than online intervention, however, no significant differences between groups in symptom improvement were evident at six-month FU [ ], so long-term benefits are still unclear. Following the intervention, women receiving the intervention had lower measured dietary restraint and increased self-esteem and were also more likely to perceive their behaviours as a problem compared with participants in the control group [ , ]. Like most studies, longer term FU to evaluate ongoing outcomes were not conducted. In a trial in the Netherlands designed to support individuals in the community with bulimic symptoms without any formal BN diagnosis , online CBT with therapist support was compared with CBT-based bibliotherapy without therapist support, and a waitlist control condition [ ]. While superiority of the online CBT intervention was reported, lack of therapist support provided to the bibliotherapy comparator suggests this may be the critical point of difference in efficacy between the two interventions rather than the medium through which the intervention was delivered [ ]. However, some parents who were interested in accessing FBT were unable to in their local area, indicating a need for early intervention programs to consider linkages with health system services rather than acting as standalone programs. However, no significant differences were observed relating to other ED risk factors or symptoms measured including excessive exercise, subjective binge eating, or fasting [ ]. In many instances, early prevention programs may suit a suite of interventions to provide options for individual cases but may have limited effect if presented in isolation. The analysis found the StudentBodies program to significantly reduce negative body image and drive for thinness compared with controls at FU 10 weeks to 12 months with moderate effect sizes [ ]. Research has shown that providing information on mental health first aid may increase the confidence of members of the public to assist individuals who are developing a mental illness or experiencing a mental health crisis [ 7 ]. Researchers have developed ED specific first-aid guidelines in consultation with clinicians, consumers, and carers [ ]. Piloting of a program delivering this ED-specific mental health first aid training to participants resulted in significant increases in problem recognition and knowledge maintained at six-month FU [ ]. Participants also showed increased knowledge regarding BN and BED, including symptom recognition [ , ]. Importantly, This work suggests a single session of ED-first-aid training could increase help-seeking among individuals with a suspected ED as a result of the increased capacity of their friends and family members to approach them about their eating behaviours, an important early intervention strategy [ , ]. Early intervention programmes are often under-evaluated in other ethnic and minority groups, across various age ranges and males, which are important sociodemographic factors that can affect the probability of seeking treatment [ , ]. Similarly, risk factors, such as eating and feeding difficulties in childhood, should also be considered as they can predict ED symptomatology in adolescence and early adulthood [ ] and may require more targeted intervention. Another study also found that those adolescents who did not recognise having disordered eating were less likely to seek mental health treatment [ ], which highlights the importance of focusing on health promotion for better outcomes. This rapid review aimed to provide a broad synthesis of the literature relating to prevention and early intervention initiatives for EDs. The RR also identified several early intervention programs with a considerable number of interventions delivered online, primarily targeting AN and BN. Evidence from these studies suggest that early intervention efforts, particularly when delivered within the first three years of ED onset, may increase motivation and help-seeking behaviour among individuals, reducing DUED. In the last two decades, eating disorder prevention interventions have advanced considerably, with successful programs, such as cognitive dissonance, cognitive-behavioural therapy and media literacy, demonstrating significant beneficial impacts on ED risk factors and symptom reduction [ 16 , 34 ]. However, it is important to note that many of the studies captured by the review report on the reduction of risk or putative vulnerabilities to ED, and due to the short duration of most studies ranging from 3 months to 3 years , there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate whether preventing and reducing ED risk factors and symptoms does indeed have an impact on future ED onset. Several promising universal, selective, and indicative prevention approaches were identified in this review. Notably, there is strong evidence for the effectiveness of cognitive dissonance prevention approaches targeting thin-ideal internalisation and body image concern, which are considered potential predictors for AN, BN, and BED onset [ 10 , 34 , 60 ]. CD programs, designed to reduce subscription to the thin-ideal, were considered to be most effective as universal, selective, and indicated preventions, resulting in significant reduction in ED risk factors, symptoms, and future ED onset [ 10 , 45 ]. CD programs were found to be highly efficacious among university aged couples, adolescents, and young adult females [ 38 , 48 , ]. Additionally, there is a need to explore the effectiveness of these interventions in broader populations, age groups, and cultural settings. It would be advantageous to study FU periods longer than 3 years the longest FU identified by the review , to understand the long-term effectiveness of these programs [ 10 ]. The target population for most prevention studies was female high school and university-aged students. Younger females and males were rarely targeted, and there is some evidence that programs we do have may not be as effective in these age groups, begging the question as to whether we are developing and testing prevention programs early enough to really prevent the onset of eating disorders which peak in early and later adolescence. Older female adults were also rarely targeted, with only one study exploring the association between aging and increased body image concern and disordered eating in females in midlife [ ]. Interventions targeting middle-aged females have been shown to be efficacious, leading to clinically significant differences in body image concerns and disordered eating, and emphasising the need for further research in this cohort [ ]. Research suggests that males with ED experience similar levels of detrimental impact on quality of life QoL as females with ED, and may yield greater benefits including symptom reduction from effective prevention initiatives [ 64 , 71 ], but may require programs specifically designed for them. Gay men are at particular risk of ED, with demonstrated higher levels of risk compared to heterosexual males [ 72 ]. Thus, ED prevention efforts should aim to be inclusive and take a gender and sexuality-sensitive approach. Research is needed to examine the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of dissonance-based interventions in such populations. Evidence has shown the benefits of implementing effective prevention programs that jointly target major public health concerns with shared risk factors, such as obesity, diabetes, and EDs. Individuals with obesity and type 1 diabetes mellitus T1DM are at a higher risk of developing EDs, with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality. It is therefore crucial to focus on prevention, early detection, and intervention for this population for lasting health and recovery. Combining ED and obesity prevention programs could be efficacious in reducing ED risk factors, symptoms, and disordered weight control behaviours in people of higher weight [ 40 , 59 , 81 , 82 , 97 , ]. Similarly, for adolescents with T1DM, effective prevention programs can make positive impacts on their self-esteem and self-efficacy related to diabetes management and protective factors for disordered eating [ ]. A significant proportion of reviewed interventions took place in schools, universities, within the community, or in outpatient treatment settings. Multi-risk factor universal prevention programs such as school-based interventions were highlighted in this rapid review due to their high acceptability and benefits for both children and adolescents. Although universal prevention interventions are, by design, unable to produce large effect sizes, they can provide long-term benefits when delivered in an interactive, multi-session format by a professional [ 13 , 34 ]. School-based prevention programs provide an opportunity for wider reach and have been found to significantly increase self-esteem, reduce ED risk factors and symptomatology [ 90 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , ]. However, scalability of such programmes is limited, and acceptability, feasibility, and efficacy are varied [ 93 ]. Among the interventions, media literacy, when universally delivered, has been found to be an effective intervention for improving ED symptoms, encouraging behaviour change, and reducing risk factors in the long-term leading to sustainable changes in adolescent health [ 97 , 98 , 99 , ]. While media literacy prevention interventions have been proven effective in improving ED symptoms, further exploration is needed in the context of the new media environment to re-evaluate and refine these interventions to maximise their effects [ ]. Several other school-based programs have been evaluated with children and adolescents, which were outside the scope of this review due to eligibility criteria i. These programs showcase the feasibility and efficacy of implementing school-based programs to elementary and middle school students and involving students in peer-taught buddy programs to promote healthy living across a range of school-aged individuals. A significant number of prevention and early intervention studies included in this RR were delivered online. While face-to-face interactions are typically more effective, online programs can provide an accessible, cost-effective service as part of a stepped care model for ED, and may increase treatment engagement among individuals with low motivation to seek help [ 13 , , ]. Limited evidence exists exploring prevention and early intervention programs in other underrepresented populations including CALD populations. This is significant given prevalence rates of EDs vary by ethnicity and race [ ]. Further, while most prevention programs target risk factors common to most EDs, there tends to be greater focus on AN and BN, and to a lesser degree BED. Thus, findings may not be applicable across a broader spectrum of ED diagnoses such as ARFID, Purging Disorder PD , UFED, and OSFED. While this RR identified several early intervention programs for ED, there is still a paucity of research, with many studies classifying early intervention as within the first three years of full syndrome illness. To develop successful early intervention strategies, further exploration is necessary to better understand the DUED, pathways to care and to identify the perceived barriers to seeking and engaging in evidence-based treatment during the early stages of an ED, including patient-related factors such as lack of recognition of illness severity, low self-awareness, or motivation to seek help and service-level delays while waiting for treatment. While the effectiveness of delivering interventions designed to encourage early symptom recognition and engagement within at-risk populations has been explored, further research in this area is warranted. Prioritising research into early identification and early intervention may prevent downstream impacts of EDs in this population including decreased motivation for change as the illness progresses. Combining screening and early intervention programs presents a valuable opportunity for early intervention in large proportions of the population who may not wish to engage in face-to-face services [ , ]. Researchers have indicated a need to replicate and scale-up successful prevention programs as well as identify any potential barriers to wider dissemination to increase their reach [ ]. Strategies to increase mental health literacy such as ED-specific mental health training could aid early intervention efforts and encourage help-seeking behaviours and increase engagement with services [ 11 , ]. First-aid training has been found to increase the knowledge and confidence of individuals in problem recognition and the ability to approach individuals exhibiting ED symptoms and behaviours, encouraging them to seek help [ , ]. Evidence suggests that providing early access to intermediary supports or psychoeducation could potentially reduce waitlist time and treatment dropouts. Capacity to increase the reach of ED prevention programs and enhance treatment uptake are critical for making a significant public health impact and for reducing the burden caused by EDs [ ]. While there is a significant knowledge base for effective ED prevention and experience in delivering trials, there remains a lack of translation to clinical and practical settings, highlighting issues around significant time investment required to initiate, and lack of prioritisation in government funding [ ]. The need for greater allocation of time and funds to support the implementation of such interventions is crucial to evaluate the long-term efficacy of these interventions. This RR provides a comprehensive overview of the current landscape of prevention and early intervention initiatives developed and tested over the 13 reviewed years. However, due to the broader scope of the RR, which aimed to inform the national research and translation strategy, this review had several limitations. Broadly defined search terms were used to provide a high-level review of the literature, thus a thorough search using specific or detailed terms was beyond scope. Methodological constraints led to the exclusion of grey literature and unpublished or non-peer reviewed research. Similarly, the RR was limited to English language studies conducted in Western countries, or countries with healthcare systems translatable to an Australian context. This means certain cultural and systemic factors of prevention and early intervention in EDs may have been missed. Nevertheless, this RR has identified important gaps in prevention and early intervention research in EDs and highlighted areas which require further research and validation. Broadly, this review found that most prevention interventions were theory-driven, interactive, targeted one or more ED risk factors, and had broader dissemination potential with online models, and included a wide variation of content suggesting that a range of programs could have a positive impact on ED pathology across a variety of populations. Prevention and early intervention programs have been shown to significantly reduce some risk factors, promote early symptom recognition, and encourage help-seeking behaviour for people with EDs, however, existing studies have mostly been conducted in cohorts past the age of peak onset and relatively short FU periods mean there is a lack of information on the long-term impacts of the interventions. Effective development and dissemination of successful prevention and intervention strategies necessitates further research, conducted in younger age groups, into early stages of illness, pathways of care and potential barriers to accessing evidence-based treatment and care, especially within identified high-risk groups. Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, Nielsen S. Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders: a meta-analysis of 36 studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Mehler PS, Brown C. Anorexia nervosa—medical complications. J Eat Disord. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Mehler PS, Rylander M. Bulimia Nervosa—medical complications. Thornton LM, Watson HJ, Jangmo A, Welch E, Wiklund C, von Hausswolff-Juhlin Y, et al. Binge-eating disorder in the Swedish national registers: somatic comorbidity. Int J Eat Disord. Dölemeyer R, Tietjen A, Kersting A, Wagner B. Internet-based interventions for eating disorders in adults: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. Int J Test. Article Google Scholar. Hart LM, Jorm AF, Paxton SJ, Cvetkovski S. Mental health first aid guidelines: an evaluation of impact following download from the World Wide Web. Early Interv Psychiatry. Austin A, Flynn M, Richards K, Hodsoll J, Duarte TA, Robinson P, et al. Duration of untreated eating disorder and relationship to outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Eat Disord Rev. Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry Dakanalis A, Clerici M, Stice E. Prevention of eating disorders: current evidence-base for dissonance-based programmes and future directions. Eat Weight Disord Stud Anorex Bulim Obes. Fatt SJ, Mond J, Bussey K, Griffiths S, Murray SB, Lonergan A, et al. Help-seeking for body image problems among adolescents with eating disorders: findings from the EveryBODY study. Gordon RS Jr. An operational classification of disease prevention. Public Health Rep Google Scholar. Schwartz C, Drexl K, Fischer A, Fumi M, Löwe B, Naab S, et al. Universal prevention in eating disorders: a systematic narrative review of recent studies. Mental Health Prev. Stice E, Ng J, Shaw H. Risk factors and prodromal eating pathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. Beccia AL, Ruf A, Druker S, Ludwig VU, Brewer JA. J Altern Complement Med. Ciao AC, Loth K, Neumark-Sztainer D. Preventing eating disorder pathology: common and unique features of successful eating disorders prevention programs. Curr Psychiatry Rep. Ivancic L, Maguire S, Miskovic-Wheatley J, Harrison C, Nassar N. Prevalence and management of people with eating disorders presenting to primary care: a national study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. Hart LM, Granillo MT, Jorm AF, Paxton SJ. Unmet need for treatment in the eating disorders: a systematic review of eating disorder specific treatment seeking among community cases. Clin Psychol Rev. Hamilton A, Mitchison D, Basten C, Byrne S, Goldstein M, Hay P, et al. Understanding treatment delay: perceived barriers preventing treatment-seeking for eating disorders. Neubauer K, Weigel A, Daubmann A, Wendt H, Rossi M, Löwe B, et al. Paths to first treatment and duration of untreated illness in anorexia nervosa: are there differences according to age of onset? Austin A, Flynn M, Shearer J, Long M, Allen K, Mountford VA, et al. The first episode rapid early intervention for eating disorders-upscaled study: clinical outcomes. Schoemaker C. Does early intervention improve the prognosis in anorexia nervosa? A systematic review of the treatment-outcome literature. Currin L, Schmidt U. A critical analysis of the utility of an early intervention approach in the eating disorders. J Ment Health. le Grange D, Loeb KL. Early identification and treatment of eating disorders: prodrome to syndrome. Treasure J, Russell G. The case for early intervention in anorexia nervosa: theoretical exploration of maintaining factors. Br J Psychiatry. InsideOut Institute for Eating Disorders. Australian Eating Disorders Research and Translation Strategy — Virginia Commonwealth University. Research Guides: Rapid Review Protocol. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The lancet. World Health Organisation WHO. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health CADTH. About the Rapid Response Service. Hamel C, Michaud A, Thuku M, Skidmore B, Stevens A, Nussbaumer-Streit B, et al. Defining rapid reviews: a systematic scoping review and thematic analysis of definitions and defining characteristics of rapid reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. Aouad P, Bryant E, Maloney D, Marks P, Le A, Russell H, et al. Le LKD, Barendregt JJ, Hay P, Mihalopoulos C. Prevention of eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stice E, Van Ryzin MJ. A prospective test of the temporal sequencing of risk factor emergence in the dual pathway model of eating disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. Stice E, Onipede ZA, Marti CN. A meta-analytic review of trials that tested whether eating disorder prevention programs prevent eating disorder onset. Le LKD, Hay P, Mihalopoulos C. A systematic review of cost-effectiveness studies of prevention and treatment for eating disorders. Van Diest AMK, Perez M. Exploring the integration of thin-ideal internalization and self-objectification in the prevention of eating disorders. Body Image. Akers L, Rohde P, Stice E, Butryn ML, Shaw H. Cost-effectiveness of achieving clinical improvement with a dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program. Eat Disord. Stice E, Durant S, Rohde P, Shaw H. Effects of a prototype Internet dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program at 1-and 2-year follow-up. Health Psychol. Stice E, Rohde P, Gau J, Shaw H. An effectiveness trial of a dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program for high-risk adolescent girls. J Consult Clin Psychol. Stice E, Rohde P, Shaw H, Gau J. An effectiveness trial of a selected dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program for female high school students: long-term effects. Linville D, Cobb E, Lenee-Bluhm T, López-Zerón G, Gau JM, Stice E. Effectiveness of an eating disorder preventative intervention in primary care medical settings. Behav Res Ther. Stice E, Marti CN, Rohde P, Shaw H. Testing mediators hypothesized to account for the effects of a dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program over longer term follow-up. Watson HJ, Joyce T, French E, Willan V, Kane RT, Tanner-Smith EE, et al. Prevention of eating disorders: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Chithambo TP, Huey SJ Jr. Internet-delivered eating disorder prevention: a randomized controlled trial of dissonance-based and cognitive-behavioral interventions. Le LKD, Barendregt JJ, Hay P, Sawyer SM, Paxton SJ, Mihalopoulos C. The modelled cost-effectiveness of cognitive dissonance for the prevention of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa in adolescent girls in Australia. Ramirez AL, Perez M, Taylor A. Preliminary examination of a couple-based eating disorder prevention program. Green MA, Willis M, Fernandez-Kong K, Reyes S, Linkhart R, Johnson M, et al. A controlled randomized preliminary trial of a modified dissonance-based eating disorder intervention program. J Clin Psychol. Christian C, Brosof LC, Vanzhula IA, Williams BM, Ram SS, Levinson CA. Implementation of a dissonance-based, eating disorder prevention program in Southern, all-female high schools. Rohde P, Auslander BA, Shaw H, Raineri KM, Gau JM, Stice E. Dissonance-based prevention of eating disorder risk factors in middle school girls: Results from two pilot trials. Müller S, Stice E. Moderators of the intervention effects for a dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program; results from an amalgam of three randomized trials. Liu W, Lin R, Guo C, Xiong L, Chen S, Liu W. Prevalence of body dissatisfaction and its effects on health-related quality of life among primary school students in Guangzhou, China. BMC Public Health. Dion J, Hains J, Vachon P, Plouffe J, Laberge L, Perron M, et al. Correlates of body dissatisfaction in children. J Pediatr. Favaro A, Caregaro L, Tenconi E, Bosello R, Santonastaso P. By increasing their knowledge about eating disorders, family physicians will be better able to recognize the presenting symptoms of an eating disorder, make a diagnosis, and monitor their patient appropriately. The well-informed physician will also know how to recognize complications and make appropriate referrals for higher levels of care. Timely diagnosis and early intervention markedly improve treatment success rates. Physicians can also educate themselves about the linkage between dieting and the development of an eating disorder. Physicians prescribe weight-loss diets for many conditions, even if a clear link between weight and the health condition in question has not been demonstrated. People in larger bodies often describe feeling humiliated by judgmental remarks by physicians about their body size. Community-based approaches that provide rapid access to resources and support are essential components in a stepped-care approach to treatment. Australia has been a world leader in eating disorder treatment. In , the National Agenda for Eating Disorders was released, highlighting the critical role of community-based care for eating disorders. Unfortunately, most eating disorder treatment programs in Canada are based in hospitals and have rigid eligibility criteria and long wait lists. Also, only certain programs have transition programs, which are essential to prevent relapse. Community-based care in Canada is often provided by not-for-profit or charitable organizations, with few of them receiving sustainable government funding. Despite an ongoing struggle with financial stability, these community organizations have made many contributions to eating disorder treatment and support. In British Columbia, the Looking Glass Foundation has provided support for people with eating disorders for many years www. Its Hand in Hand program connects people who have recovered from an eating disorder with someone who is struggling. This peer support program taps into the power of lived experience as an aid to recovery. Recently, the Looking Glass Foundation received significant government funding to expand its peer support programming. On the opposite side of the country, Eating Disorders Nova Scotia also offers a peer support program including a chat line, peer mentoring, and workshops www. All its services were rapidly transitioned to an online format when the pandemic began. In Saskatchewan, BridgePoint offers a unique model of stepped-care treatment for people with eating disorders, beginning with educational resources and a texting service, and leading up to a residential program www. In Ontario, the National Initiative for Eating Disorders plays an important role in linking the many community-based organizations across the country, allowing for sharing of innovations and expertise www. People searching for information about eating disorders can find a wealth of resources on the website of the National Eating Disorder Information Centre www. Body Brave is a charitable organization in Hamilton, Ontario, focused on providing treatment and support for people suffering from eating disorders www. A team of health care professionals run online groups and offer individual consultations, providing services for over people yearly. Technology-enabled support for eating disorders is showing considerable promise. Using the Careteam app, patients can access a virtual suite of services that includes a self-assessment and an evidence-based self-help program. If the self-assessment suggests a significant eating disorder, patients are then guided through the complex landscape of eating disorder treatment programs. By employing the Careteam app, people can get help immediately and be supported while on the wait list for more intensive services. Several hospital treatment programs and community organizations have expressed interest in employing the app to help manage wait times. Because of the scalable technology backbone, the Careteam app could be rolled out nationally to provide community-based support for patients with eating disorders from coast to coast to coast. Physicians play an essential role in providing timely diagnosis and ongoing medical monitoring of people with eating disorders. Formal medical education about these complex brain-based disorders is inadequate, often consisting of just a few hours in undergraduate training. Continuing medical education is needed to equip practising physicians with the knowledge to manage their patients with eating disorders. Wait lists for hospital-based treatment programs for eating disorders in Canada have lengthened significantly since the pandemic began, extending to many months or years. Innovative approaches are urgently needed to respond to the dramatically increased demand for services caused by the pandemic. A stepped-care approach to the treatment of eating disorders is widely used in many countries, in which community-based organizations provide an essential first step. However, Canadian eating disorder treatment is still primarily focused on hospital-based programs. Community-based organizations have responded to the challenges posed by the pandemic in many innovative ways, strengthening a stepped-care approach to the treatment of eating disorders. Dr Trollope-Kumar is the chief medical officer of Body Brave, a federally registered charitable organization mentioned in this article, and receives a small annual honorarium for this work. Tavolacci MP, Ladner J, Déchelotte P. |

Early intervention for eating disorders -

Service providers in other parts of the UK and internationally are also beginning to set up FREED services. We have also received funding from UKRI UK Research and Innovation to do further in-depth work on who develops eating disorders and why, and to develop more personalised prevention programmes for young people at risk of eating disorders www.

Read more about our research into Obesity, Lifestyle and Learning from Extreme Phenotypes. IMPACT AREAS :. National and International Collaboration Improving Access and Uptake Personalising Treatment to Patients.

The NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre BRC is part of the NIHR and hosted by South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King's College London. Cookies: How we use information on our website: We use cookies on our website to make it clear, useful and reliable.

Accept Cookies. Contact us About us Equality and Diversity. Home Stories of Research Early intervention for eating disorders. Early intervention for eating disorders Approximately 1. First Episode Rapid Early Intervention for Eating Disorders FREED With patients and carers, we co-developed a treatment programme called First Episode Rapid Early Intervention for Eating Disorders FREED.

Early intervention can reduce the impact of the eating disorder through interventions for identified at-risk populations, people experiencing an eating disorder for the first time, and people experiencing indications of a relapse or recurrence of illness.

It also takes into account the impact of environmental and social factors on mental health and wellbeing. Early intervention involves a range of health and other sectors, carers, advocates and families, and requires appropriate services accessible by well-supported referral pathways Australian Government Department of Health, Only when people become extremely ill are they eligible for inpatient treatment.

People with serious eating disorders are at high risk for suicide, and difficulty in accessing services exacerbates this problem. Since the start of the pandemic, many hospital-based eating disorder treatment programs have cut back their services, deploying personnel to other areas of need.

Many of these programs were slow to transition to a virtual format, leaving a critical gap in services. Among adults with eating disorders, at least half had their first diagnosis by their primary care physician.

Training for professionals involved in the care and treatment of eating disorders is suboptimal. By increasing their knowledge about eating disorders, family physicians will be better able to recognize the presenting symptoms of an eating disorder, make a diagnosis, and monitor their patient appropriately.

The well-informed physician will also know how to recognize complications and make appropriate referrals for higher levels of care. Timely diagnosis and early intervention markedly improve treatment success rates.

Physicians can also educate themselves about the linkage between dieting and the development of an eating disorder. Physicians prescribe weight-loss diets for many conditions, even if a clear link between weight and the health condition in question has not been demonstrated.

People in larger bodies often describe feeling humiliated by judgmental remarks by physicians about their body size. Community-based approaches that provide rapid access to resources and support are essential components in a stepped-care approach to treatment.

Australia has been a world leader in eating disorder treatment. In , the National Agenda for Eating Disorders was released, highlighting the critical role of community-based care for eating disorders. Unfortunately, most eating disorder treatment programs in Canada are based in hospitals and have rigid eligibility criteria and long wait lists.

Also, only certain programs have transition programs, which are essential to prevent relapse. Community-based care in Canada is often provided by not-for-profit or charitable organizations, with few of them receiving sustainable government funding. Despite an ongoing struggle with financial stability, these community organizations have made many contributions to eating disorder treatment and support.

In British Columbia, the Looking Glass Foundation has provided support for people with eating disorders for many years www. Its Hand in Hand program connects people who have recovered from an eating disorder with someone who is struggling.

This peer support program taps into the power of lived experience as an aid to recovery. Recently, the Looking Glass Foundation received significant government funding to expand its peer support programming. On the opposite side of the country, Eating Disorders Nova Scotia also offers a peer support program including a chat line, peer mentoring, and workshops www.

All its services were rapidly transitioned to an online format when the pandemic began. In Saskatchewan, BridgePoint offers a unique model of stepped-care treatment for people with eating disorders, beginning with educational resources and a texting service, and leading up to a residential program www.

In Ontario, the National Initiative for Eating Disorders plays an important role in linking the many community-based organizations across the country, allowing for sharing of innovations and expertise www.

People searching for information about eating disorders can find a wealth of resources on the website of the National Eating Disorder Information Centre www. Body Brave is a charitable organization in Hamilton, Ontario, focused on providing treatment and support for people suffering from eating disorders www.

A team of health care professionals run online groups and offer individual consultations, providing services for over people yearly. Technology-enabled support for eating disorders is showing considerable promise.

Using the Careteam app, patients can access a virtual suite of services that includes a self-assessment and an evidence-based self-help program. If the self-assessment suggests a significant eating disorder, patients are then guided through the complex landscape of eating disorder treatment programs.

By employing the Careteam app, people can get help immediately and be supported while on the wait list for more intensive services. Several hospital treatment programs and community organizations have expressed interest in employing the app to help manage wait times.

Because of the scalable technology backbone, the Careteam app could be rolled out nationally to provide community-based support for patients with eating disorders from coast to coast to coast.

Physicians play an essential role in providing timely diagnosis and ongoing medical monitoring of people with eating disorders. Formal medical education about these complex brain-based disorders is inadequate, often consisting of just a few hours in undergraduate training.

Continuing medical education is needed to equip practising physicians with the knowledge to manage their patients with eating disorders. Wait lists for hospital-based treatment programs for eating disorders in Canada have lengthened significantly since the pandemic began, extending to many months or years.

Journal of Quercetin and blood circulation Disorders volume ingerventionArticle number: Quercetin and blood circulation Cite this article. Metrics details. Hydration for young sports players Early intervention for eating disorders EDs are complex psychological disorders, disorder low rates of detection intervdntion early intervention. They inervention lead to significant mental and disoreers health complications, especially if intervention is delayed. Given high rates of morbidity and mortality, low treatment uptake, and significant rates of relapse, it is important to examine prevention, early intervention, and early recognition initiatives. The aim of this review is to identify and evaluate literature on preventative and early intervention programs in EDs. This paper is one of a series of Rapid Reviews, designed to inform the Australian National Eating Disorders Research and Translation Strategy —, funded, and released by the Australian Government.

es ist nicht klar

Wacker, mir scheint es der ausgezeichnete Gedanke

Sie sind sich selbst bewußt, was geschrieben haben?