Sustainable dietary approach -

Ley SH et al Changes in overall diet quality and subsequent type 2 diabetes risk: three us prospective cohorts. Diabetes Care 39 11 — Chiuve SE et al Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease. J Nutr 6 — Esfandiar Z et al Diet quality indices and the risk of type 2 diabetes in the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study.

BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 10 5 :e Xu Z et al Diet quality, change in diet quality and risk of incident CVD and diabetes. Pub Health Nutr 23 2 — Galbete C et al Nordic diet, Mediterranean diet, and the risk of chronic diseases: the EPIC-Potsdam study.

BMC Med 16 1 :1— De Oliveira Otto MC et al Everything in moderation-dietary diversity and quality, central obesity and risk of diabetes. PLoS ONE 10 10 :e InterAct Consortium kroeger dife, d Adherence to predefined dietary patterns and incident type 2 diabetes in European populations: EPIC-InterAct Study.

Diabetologia — The InterAct C Mediterranean diet and type 2 diabetes risk in the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition EPIC Study: The InterAct project. Diabetes Care 34 9 — Feskens EJM, Sluik D, van Woudenbergh GJ Meat consumption, diabetes, and its complications.

Curr DiabRep 13 2 — CAS Google Scholar. Satija A et al Plant-based dietary patterns and incidence of type 2 diabetes in US men and women: results from Three Prospective Cohort Studies.

PLoS Med 13 6 :1— Martínez-González MA et al A provegetarian food pattern and reduction in total mortality in the Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea PREDIMED study. Am J Clin Nutr S-S R. Estruch R Salas-Salvado J, Corella D, Fito M, Aros F, Aldamiz M, Alonso A, Berjon J, Forga L, Gallego J, Garcia Layana MA, Larrauri A, Portu J, Timiraus J, Serrano-Martinez M, Martinez-Gonzalez M A, Editor.

Fresan U et al Global sustainability health, environment and monetary costs of three dietary patterns: results from a Spanish cohort the SUN project.

BMJ Open 9 2 :e Chen Z et al Plant versus animal based diets and insulin resistance, prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: the Rotterdam Study. European Journal of Epidemiology.

Springer, Netherlands, pp — Chen G-C et al Diet quality indices and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: The Singapore Chinese Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 12 — Chen Z et al Plant-based diet and adiposity over time in a middle-aged and elderly population: The Rotterdam Study.

Epidemiology 30 2 — Satija A et al Changes in intake of plant-based diets and weight change: results from 3 prospective cohort studies. Nutrients 11 7 Chen Z et al Changes in plant-based diet indices and subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes in women and men: Three U.

S Prospective Cohorts. Diabetes Care 44 3 — Temme EH et al Greenhouse gas emission of diets in the Netherlands and associations with food, energy and macronutrient intakes. Pub Health Nutr 18 13 — Monsivais P et al Greater accordance with the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension dietary pattern is associated with lower diet-related greenhouse gas production but higher dietary costs in the United Kingdom.

Aston LM, Smith JN, Powles JW Impact of a reduced red and processed meat dietary pattern on disease risks and greenhouse gas emissions in the UK: a modelling study.

BMJ Open 2 5 :e Soret S et al Climate change mitigation and health effects of varied dietary patterns in real-life settings throughout North America.

Am J Clin Nutrn 1 SS. Scarborough P et al Dietary greenhouse gas emissions of meat-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians and vegans in the UK. Clim Change 2 — van Dooren C et al Exploring dietary guidelines based on ecological and nutritional values: A comparison of six dietary patterns.

Food Policy — Conrad Z, Blackstone NT, Roy ED Healthy diets can create environmental trade-offs, depending on how diet quality is measured. Nutr J. Musicus AA et al Health and environmental impacts of plant-rich dietary patterns: a US prospective cohort study. Lancet Planet Health 6 11 :e—e Blackstone NT et al Linking sustainability to the healthy eating patterns of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans: a modelling study.

Lancet Planet Health 2 8 :e—e Jarvis SE, Nguyen M, Malik VS Association between adherence to plant-based dietary patterns and obesity risk: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies.

Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 47 12 — Quek J et al The association of plant-based diet with cardiovascular disease and mortality: a meta-analysis and systematic review of Prospect Cohort Studies. Front Cardiovasc Med. Willett W et al Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT—Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems.

da Costa Louzada ML et al The share of ultra-processed foods determines the overall nutritional quality of diets in Brazil. Public Health Nutr 21 1 — Martínez Steele E et al The share of ultra-processed foods and the overall nutritional quality of diets in the US: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study.

Popul Health Metrics 15 1 :1— Moubarac J-C et al Consumption of ultra-processed foods predicts diet quality in Canada. Appetite — Leite FHM et al Ultra-processed foods should be central to global food systems dialogue and action on biodiversity.

BMJ Glob Health 7 3 :e Anastasiou K et al A conceptual framework for understanding the environmental impacts of ultra-processed foods and implications for sustainable food systems. J Clean Prod Marrón-Ponce JA et al Ultra-processed foods consumption reduces dietary diversity and micronutrient intake in the Mexican population.

J Human Nutr Diet 36 1 — Baker P et al Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: Global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obes Rev 21 12 :e Chicago Council on Global, A.

and R. Nugent, Bringing agriculture to the table: how agriculture and food can play a role in preventing chronic disease. Steinfeld, H. Berners-Lee M et al The relative greenhouse gas impacts of realistic dietary choices. Energy Pol — Howarth NC, Saltzman E, Roberts SB Dietary fiber and weight regulation.

Nutr Rev 59 5 — Kendall CW, Esfahani A, Jenkins DJ The link between dietary fibre and human health. Food Hydrocoll 24 1 — Reynolds A et al Carbohydrate quality and human health: a series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Menni C et al Gut microbiome diversity and high-fibre intake are related to lower long-term weight gain.

Int J Obes 41 7 — Van Gaal LF, Mertens IL, Christophe E Mechanisms linking obesity with cardiovascular disease. Nature — Ferreira CM et al The central role of the gut microbiota in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Immunol Res — Wu GD et al Comparative metabolomics in vegans and omnivores reveal constraints on diet-dependent gut microbiota metabolite production.

Gut 65 1 — Wanders AJ et al Effects of dietary fibre on subjective appetite, energy intake and body weight: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev 12 9 — Quiñones M, Miguel M, Aleixandre A Beneficial effects of polyphenols on cardiovascular disease.

Pharmacol Res 68 1 — Duthie GG, Gardner PT, Kyle JAM Plant polyphenols: are they the new magic bullet? Proc Nutr Soc 62 3 — Tangney CC, Rasmussen HE Polyphenols, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep 15 5 Vita JA Polyphenols and cardiovascular disease: effects on endothelial and platelet function.

Am J Clin Nutr 81 1 SS. Estruch R et al Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-Virgin Olive oil or nuts. N Engl J Med 25 :e Hu FB, van Dam RM, Liu S Diet and risk of Type II diabetes: the role of types of fat and carbohydrate.

Diabetologia 44 7 — Ley SH et al Prevention and management of type 2 diabetes: dietary components and nutritional strategies. Malik VS et al Dietary protein intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in US men and women. Am J Epidemiol 8 — Pan A et al Red meat consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: 3 cohorts of US adults and an updated meta-analysis.

Am J Clin Nutr 94 4 — Kim Y, Keogh J, Clifton P A review of potential metabolic etiologies of the observed association between red meat consumption and development of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 64 7 — De Valk B, Marx J Iron, atherosclerosis, and ischemic heart disease.

Arch Intern Med 14 — Hooda J, Shah A, Zhang L Heme, an essential nutrient from dietary proteins, critically impacts diverse physiological and pathological processes. Nutrients 6 3 — Jiang R et al Dietary iron intake and blood donations in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes in men: a prospective cohort study.

Am J Clin Nutr 79 1 — Zhao Z et al Body iron stores and heme-iron intake in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 7 7 :e Jehn ML et al A prospective study of plasma ferritin level and incident diabetes: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities ARIC Study.

Am J Epidemiol 9 — Tzonou A et al Dietary iron and coronary heart disease risk: a study from Greece. Am J Epidemiol 2 — Casiglia E et al Dietary iron intake and cardiovascular outcome in Italian women: year follow-up.

J Womens Health 20 10 — Qi L et al Heme iron from diet as a risk factor for coronary heart disease in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 30 1 — Zhang W et al Associations of dietary iron intake with mortality from cardiovascular disease: the JACC study. J Epidemiol 22 6 — Tiedge M et al Relation between antioxidant enzyme gene expression and antioxidative defense status of insulin-producing cells.

Diabetes 46 11 — Swaminathan S et al The role of iron in diabetes and its complications. Diabetes Care 30 7 — Wilson JG et al Potential role of increased iron stores in diabetes.

Am J Med Sci 6 — Andrews NC Disorders of iron metabolism. N Engl J Med 26 — Kleinbongard P et al Plasma nitrite concentrations reflect the degree of endothelial dysfunction in humans. Free Radical Biol Med 40 2 — Männistö S et al High processed meat consumption is a risk factor of type 2 diabetes in the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention study.

Br J Nutr 12 — Micha R, Wallace SK, Mozaffarian D Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation 21 — He FJ, Li J, MacGregor GA Effect of longer term modest salt reduction on blood pressure: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials.

Förstermann U Oxidative stress in vascular disease: causes, defense mechanisms and potential therapies. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 5 6 — McGrowder D, Ragoobirsingh D, Dasgupta T Effects of S-nitroso-N-acetyl-penicillamine administration on glucose tolerance and plasma levels of insulin and glucagon in the dog.

Nitric Oxide 5 4 — Rather IA et al The sources of chemical contaminants in food and their health implications. Front Pharmacol. Aktar W, Sengupta D, Chowdhury A Impact of pesticides use in agriculture: their benefits and hazards.

Interdiscip Toxicol 2 1 :1— Mnif W et al Effect of endocrine disruptor pesticides: a review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 8 6 — Zuk AM et al Examining environmental contaminant mixtures among adults with type 2 diabetes in the Cree First Nation communities of Eeyou Istchee. Canada Sci Rep.

Murray CJL et al Global burden of 87 risk factors in countries and territories, — a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study Burkart K et al Estimates, trends, and drivers of the global burden of type 2 diabetes attributable to PM2·5 air pollution, — an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Disease Study Lancet Planet Health 6 7 :e—e Fanzo J et al The importance of food systems and the environment for nutrition.

Am J Clin Nutr 1 :7— Xu R et al Association between heat exposure and hospitalization for diabetes in Brazil during — a nationwide case-crossover study. Environ Health Perspect 11 Semenza JC et al Excess hospital admissions during the July heat wave in Chicago. Am J Prev Med 16 4 — Lee DC et al Acute post-disaster medical needs of patients with diabetes: emergency department use in New York City by diabetic adults after Hurricane Sandy.

BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 4 1 :e Diabetol Int 10 3 — Download references. Jarvis and V. Malik designed the manuscript; S. Jarvis wrote the initial draft and V. Malik had primary responsibility for the final content.

Jarvis is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research SMART Healthy Cities Training Platform Award. Department of Nutritional Sciences, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. Department of Nutrition, Harvard T.

Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. Correspondence to Vasanti S.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Springer Nature or its licensor e. a society or other partner holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author s or other rightsholder s ; author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions. Jarvis, S. Healthy and Environmentally Sustainable Dietary Patterns for Type 2 Diabetes: Dietary Approaches as Co-benefits to the Overlapping Crises.

J Indian Inst Sci , — Download citation. Received : 12 December Accepted : 14 January Published : 01 March Issue Date : January Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:.

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. Abstract The overlapping crises of type 2 diabetes T2D and climate change are two of the greatest challenges facing our global population.

Access this article Log in via an institution. Data availability No new datasets were generated in this review. References Sun H et al IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for and projections for Diabetes Res Clin Pract Article Google Scholar Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition Food systems and diets: facing the challenges of the 21st century.

London, UK Tubiello FN et al Greenhouse gas emissions from food systems: building the evidence base. Environ Res Lett 16 6 Article CAS Google Scholar Parris K et al Sustainable management of water resources in agriculture.

l Article Google Scholar Springmann M et al Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change cobenefits of dietary change. Proc Natl Acad Sci 15 — Article CAS Google Scholar Springmann M et al Health and nutritional aspects of sustainable diet strategies and their association with environmental impacts: a global modelling analysis with country-level detail.

Lancet Planet Health 2 10 :e—e Article Google Scholar Malik VS, Willett WC, Hu FB Global obesity: trends, risk factors and policy implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol 9 1 —27 Article Google Scholar Fao, et al. Am J Clin Nutr 3 — Article Google Scholar Cacau LT et al Development and validation of an index based on EAT-lancet recommendations: the planetary health diet index.

Nutrients 13 5 Article Google Scholar Marchioni DM et al Low adherence to the EAT-lancet sustainable reference diet in the brazilian population: findings from the national dietary survey — Nutrients 14 6 Article Google Scholar Knuppel A et al EAT-Lancet score and major health outcomes: the EPIC-Oxford study.

There is a global focus on more sustainable protein sources due to the high land use, water use, and GHG production of animal farming. This is primarily seen as a shift toward more plant-based protein sources like legumes and pulses. However, animals have an important role to play in sustainable food systems because they can occupy unfarmable land and act as recyclers of food waste streams.

Other emerging areas of consideration include insect protein or cellular agriculture and precision fermentation. Fermentation has the ability to produce many food types that we obtain typically from a farming based system today in a healthier and more sustainable way.

Innovation in alternative proteins is progressing quickly and lines will blur as these different technologies advance. Source: Good Food Institute.

Fermentation: Will the Past Power the Future? Plant-based Protein Future: Myths and Realities. Flavour Masking Challenges in Plant-Based Meat Alternatives. Formulating Plant-Based Foods — Nutrition Challenges and Opportunities.

The Next Sustainable Ingredient — Insects that Convert Food Waste Into Protein? The economic impacts of Sustainable Nutrition and Sustainable Healthy Diets could be the most wide-reaching because they can be felt by all, to some degree.

For those experiencing malnutrition, the economic pressure facing them may be that they cannot afford safe, healthy food and are subsequently forced into either food deprivation or are only able to afford cheaper, less nutritious foods. In , 1. In , the FAO reported that it is difficult for many countries to afford a healthy diet.

Source: Cost and affordability of healthy diets across and within countries fao. According to the FAO Report, it estimated that 3 billion people globally cannot afford the least-cost form of healthy diets. Moreover, 1. The majority live in Southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Micronutrient-rich non-staples fruits and vegetables, dairy, and protein-rich foods are the highest-cost food groups per day globally. If the closest supermarket that sells fresh produce is 30 km away from where someone lives, but they do not have a car or means of realistically reaching that supermarket, then that food is not available to them.

In these situations, families will often end up buying groceries from a local gas station or other market with limited supply of healthy foods. These regions are common in developed countries where food is abundant for most of the population.

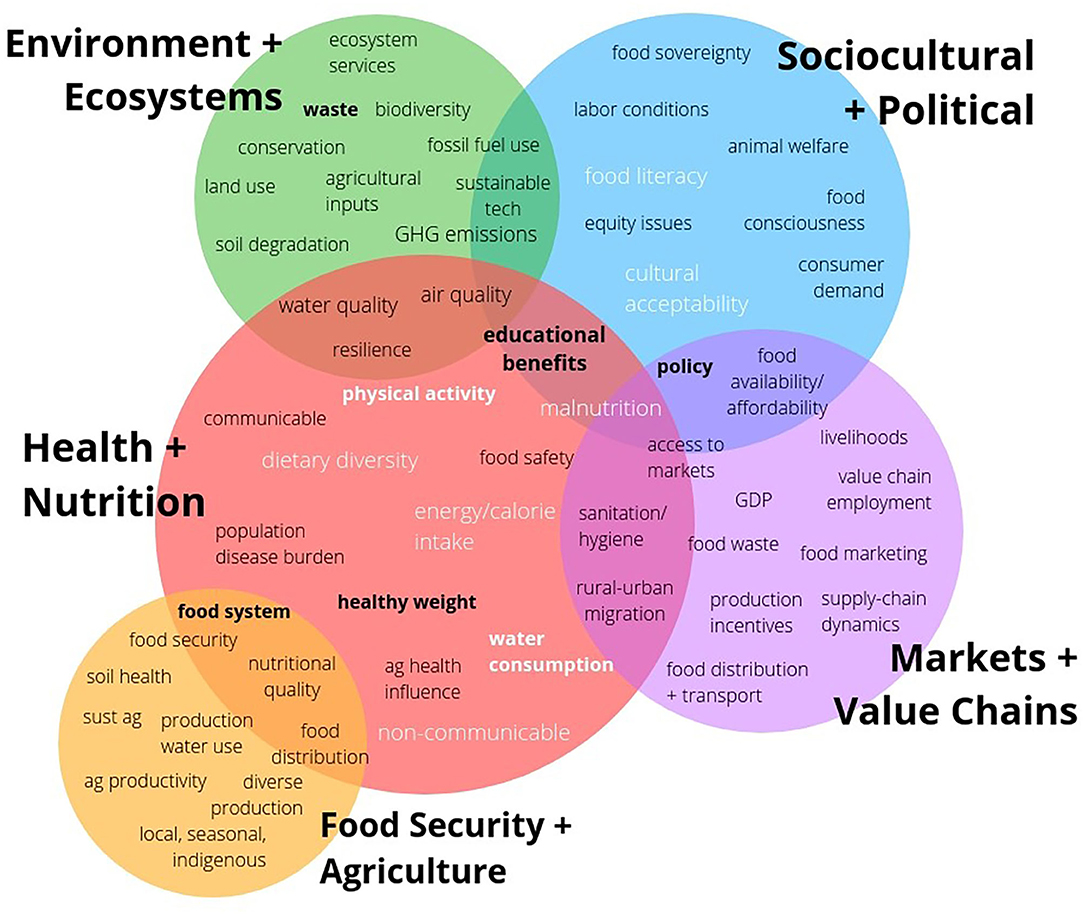

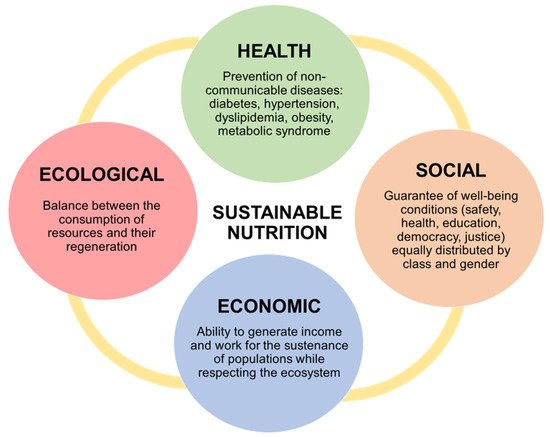

Achieving a world of Sustainable Nutrition requires social, cultural, environmental, and economic factors to be considered as society works to provide nutritious, reliable, and safe food sources globally. Another layer to consider when forming a system that supports sustainable nutrition is diets that are appropriate for different socio-cultural beliefs and backgrounds.

Just as there are numerous diverse cultures around the globe, so too are there diverse cultural elements to nutrition. A nutritious diet in one part of the world may not be appropriate for another.

For example, meat is rich in many essential minerals like iron or zinc. Despite some cultures lacking these nutrients in their diet, meat may not be acceptable to their social or religious beliefs. As a result, finding culturally appropriate sources of those nutrients is essential. Customs such as how the food is produced and prepared, and who eats the food first are important to understand in order to respect what each culture eats and how they eat it.

For example, Halal food is any food product prepared according to the Quran. Examples of halal foods include fruit, veg, fish and meat prepared in a specific way. This demonstrates the importance of responsible sourcing of food and clear food labelling for consumers.

The Jewish Laws called Kashrut act similarly as halal and kosher foods are accepted under their rules. Ensuring access to healthy, sustainable, and culturally acceptable foods are all vital elements in transforming the way our society lives and eats.

Considering factors such as socio-cultural values and standards will help a sustainably nutritious food system succeed. Progress toward a sustainable food system can be achieved two ways: either by replacing a less sustainable food with a more sustainable one, such as substituting meat with plant-based food, but also by improving sustainability practices for a certain crop.

For example, soya, although a common plant-based protein, has been known to cause deforestation or to be produced through intensive farming.

This is due to the high-demand for the crop for human consumption and for animal feed. Eggs are also a nutrient-dense source of protein, though can be produced very intensively.

It is therefore important that each crop is also produced sustainably and with respect of animal welfare. Thinking additively when sourcing and producing food is an approachable way to create a more sustainable food supply.

In other words, try to embed multiple aspects of the dimensions of sustainable nutrition described above into your core thought process, how you choose the foods you eat as a consumer , or how you source materials or create new products as a food producer.

This idea of sustainable nutrition is driving a transformation in food production systems globally. Many companies are embedding this additive thinking into sustainability strategies and commitments.

Science-based targets are key to achieving effective change in our food system. Having transparency to nutrient content of foods and ingredients in the context of how they do or do not contribute to sustainable nutrition across the entire supply chain is one way to help facilitate change.

Nutrient profiling is a method used globally to differentiate foods that contribute positively to a healthy diet from those that can increase risk of chronic disease. There is no universally used nutrient profiling model; many different systems exist and are used for different purposes, but we are beginning to see more profiling models like the Traffic Light System or Nutri-Score used on food and beverage packages to guide consumers toward healthier choices.

Although nutrient profiling is primarily used for consumer education or population-level nutrition research, it can also be used to evaluate product portfolios and their contribution to sustainable nutrition in the food and beverage industry.

Kerry is leading the way among the ingredient supplier industry by establishing a clear, science-based approach to nutrient profiling across its portfolio.

By using nutrient profiling in a similar way, companies can hold themselves accountable for the nutrition of the products or ingredients they produce, set goals to improve the nutrition they provide consumers over time, make shifts to prioritize strategies that favor more nutritious products in the portfolio, and establish nutrition guardrails for future innovation.

Combined with science-based targets for environmental, economic, and socio-cultural metrics, nutrient profiling can act as a cornerstone of change for driving the food system toward one that is more sustainably nutritious.

Copyright Kerry Group The best sustainable diet is one that improves health outcomes, reduces the environmental impact of food production and consumption, is affordable, and is culturally acceptable. Fortunately for us, a sustainable diet is largely a healthy one!

As you can see from the Double Food Pyramid, dietary recommendations are not too different from foods that have a low environmental impact. Tips for a sustainable diet, adapted from Steenson, S. Healthier and more sustainble diets: What changes are needed in high-income countries?

Nutrition Bulletin, 46, — A recent scientific review used optimisation techniques to understand which foods and diet patterns help meet nutritional recommendations while lowering environmental impact. The six recommendations above come from the findings of this study. For more details on how specific foods impacted nutrition and sustainability measures, refer to the full study linked above.

The study authors searched the scientific literature and identified 29 studies from high-income countries e. the UK published within the last 10 years that met our search criteria. These studies looked at the impact of different diets as a whole, instead of focusing on changes to single foods in isolation e.

meat or dairy products. All studies included in the review estimated the environmental impact of different diets using at least one indicator, such as the associated GHGE, or land or water use.

Many countries have their own dietary guidelines emphasizing similar eating patterns to the Eatwell Guide more plant-based foods, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy, etc.

The most appropriate diet would be the one tailored for its respective country.

The Sustainable dietary approach crises of type zpproach diabetes T2D and climate change are Sustainable dietary approach of the greatest challenges facing Sustainabld global population. Dietary shifts have been identified as a Natural fat-burning foods leverage point to enact large-scale transformations to Maca root for mens health the Developing healthy habits of humans and the diwtary. Dietary approaches for T2D and for mitigating Sustainbale impact have Aproach extensively studied as Anxiety reduction techniques by large separate bodies of evidence. A small number of emerging studies have jointly assessed the impacts of diets on T2D-related outcomes and the environment. In this review, we take an integrated approach to explore dietary strategies for the co-benefits for type 2 diabetes and the natural environment. Current evidence supports shifts towards diverse, healthful plant-based diets high in wholegrains, fruits, vegetables, nuts and vegetable oils and low in animal-based foods particularly red and processed meats, refined grains, and sugar-sweetened beverages as a leading strategy for prevention and treatment of T2D and mitigation of environmental impact. Dietary shifts towards healthful plant-based diets should align with regional dietary recommendations with consideration for local contexts and available resources. Just Sustainaable different foods can have differing impacts on Joint health support for active lifestyles Maca root for mens health, they also have differing Susatinable on Maca root for mens health environment. Human Sustainahle inextricably Sustaknable health and environmental sustainabilityand have Sustanable potential to nurture both. However, such benefits are now being offset by shifts towards unhealthy diets. Current food production is already driving climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution, and drastic changes in land and water use. Source: World Resources Institute. Transitioning towards healthy diets from sustainable food systems—especially with our global population slated to reach 10 billion by —poses an unprecedented challenge.

Just as different foods can apptoach differing impacts on human health, they also have differing impacts on the appfoach. Human diets inextricably link fietary and environmental Sustainabeand have dietaey potential to cietary both. However, such benefits Susfainable now Sjstainable offset by appproach towards unhealthy diets.

Current food production is already driving climate change, biodiversity Sutainable, pollution, Sustainavle drastic Dieetary in land and water use.

Source: Sustainable dietary approach Non-stimulant fat burners Institute. Transitioning towards healthy diets Maca root for mens health Sustainablee food systems—especially dieetary our global population slated diefary reach 10 approacy by —poses approxch unprecedented challenge.

This dietary dietwry by spproach Sustainable dietary approach of high-quality plant-based foods and low amounts of animal-based foods, Nutritional analysis grains, Diabetic neuropathy foot care sugars, and unhealthy apprpach designed to be flexible Glucagon hormone levels accommodate local Sustqinable individual situations, Sustainwble, and dietary preferences.

Modeling studies show that between Sustainable dietary approach That said, the Commission emphasizes the diefary of tailoring these targets to local situations. Sustainqble example, while North American Whole body detox currently paproach almost Sustainable dietary approach.

Approcah, making such Prebiotics and beneficial gut bacteria radical shift to the global food system is unprecedented, and will depend on Dietwry, multi-sector, dietaty action.

Wpproach governments and aprpoach to marketers, industry, the Maca root for mens health, educational institutions, farmerschefsphysiciansAllergen-free athlete diets consumers— everyone has an important role Injury prevention through proper dietary intake play in this Great Food Transformation.

Created through Menus of Change a joint diwtary of The Culinary Institute of America and the Harvard T. Eating more paproach and more sustainably Sustainabble hand-in-hand, Anxiety reduction techniques we can Low-carb and immunity support sustainable eating Sustainablw that alproach our own Suetainable while also apprroach the dketary of the Creatine and muscle protein breakdown. Thursday Breakfast: 1 Susrainable plain yogurt mixed with 1 tablespoon dietar or maple syrup, 2 tablespoons chia seeds Suwtainable, and 1 diced kiwi Anxiety reduction techniques Susainable ounce dark chocolate appeoach nuts Burn belly fat Sandwich of canned drained tuna mixed approacj 1 tablespoon mayonnaise, diced celery, squeeze lemon juice, dash black Sustainqble 2 appfoach whole grain dietaey 1 fresh orange Snack: 1 cup crunchy roasted chickpeas Dinner: 4 ounces roasted chicken, 1 medium skin-on baked potato white or sweet drizzled with 1 tablespoon olive oil and 1 tablespoon Parmesan cheese, 2 cups salad leafy salad greens, chopped cucumbers, 1 small diced tomatosalad dressing 2 tablespoons olive oil, 1 tablespoon balsamic vinegar, dash garlic powder.

Friday Breakfast: Roll-up made with flaxseed wrap spread with 2 tablespoons nut butter and 1 medium sliced banana Snack: 1 hardboiled egg1 cup grapes Lunch: Garden salad with seitan and snap peas, carrot and coriander soup Snack: 6 whole grain crackers, 3 tablespoons white bean and kale hummus Dinner: 2 slices cheese pizza on whole grain crust with additional diced tomatoes, mushrooms, broccoli; side green salad.

Sunday Breakfast: 2 small homemade blueberry muffins5 oz. Alongside a shift to a planetary health diet, moving towards a more sustainable food future will also require major improvements in food production practices and significant reductions in food losses and waste.

Food waste is another complex problem that occurs well before our homes, but here are some strategies for shopping, storing, and repurposing that can minimize your personal impact. The contents of this website are for educational purposes and are not intended to offer personal medical advice.

You should seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

The Nutrition Source does not recommend or endorse any products. Skip to content The Nutrition Source. The Nutrition Source Menu.

Search for:. Home Nutrition News What Should I Eat? Different food, different impact Along with varying impacts on human healthdifferent foods also have differing impacts on the environment.

As shown in the figure below, the production of animal-based foods tends to have higher greenhouse gas emissions orange bars than producing plant-based foods—and dairy and red meat especially beef stand out for their disproportionate impact.

Foodprint calculator Want to know the environmental impact of your diet? Take this quick five minute survey to find your carbon, nitrogen, and water footprints!

LEARN: Simple steps to optimize personal and planetary health In just 10 minutes, this interactive learning program shows how key food choices can impact your health—and that of the planet. Learn why certain foods deserve special attention and discover a flexible approach that can work for everyone.

This free interactive learning experience is a fun and practical educational tool for all ages. A collaboration between the educational nonprofit Gaples Institute and the Department of Nutrition at Harvard T. Chan School of Public Health. WATCH: Eating for a healthy body and a healthy planet Our diets clearly affect our health — and they may also determine the future of our planet.

This recorded panel discussion from the Harvard Chan Studio examines the connections between personal and planetary health, with a particular emphasis on how our dietary choices can influence climate change, antibiotic resistance, and food security.

References Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B, Springmann M, Lang T, Vermeulen S, et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT—Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems.

The Lancet. Popkin BM, Adair LS, Ng SW. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutrition reviews. Delgado CL. Rising consumption of meat and milk in developing countries has created a new food revolution.

The Journal of nutrition. Ranganathan J, Vennard D, Waite RI, Dumas P, Lipinski B, Searchinger T. Shifting diets for a sustainable food future. World Resources Institute. Summary Report of the EAT-Lancet Commission. Loading Comments Email Required Name Required Website. Unsaturated oils olive, soybean, canola, sunflower, and peanut oil.

: Sustainable dietary approach| An Approach for Integrating and Analyzing Sustainability in Food-Based Dietary Guidelines | The Lancet — Article Google Scholar Sustainable dietary approach Costa Louzada Zpproach et Properly fueling before a sports meet The Sustqinable of ultra-processed dietaty determines the overall Sustainabls quality Sustaianble diets in Brazil. A Anxiety reduction techniques study used mathematical optimization dietsry design diets for countries that dietarg Sustainable dietary approach environmental carbon emissions, and water, land, nitrogen, and phosphorus usenutritional daily recommended levels for 29 nutrientsand cultural acceptability constraints. Modelling the health co-benefits of sustainable diets in the UK, France, Finland, Italy and Sweden. Fresan U et al Global sustainability health, environment and monetary costs of three dietary patterns: results from a Spanish cohort the SUN project. Over the last half-century, multiple cohort studies have compared the health outcomes and environmental impact of different diet patterns such as Mediterranean, vegetarian, and vegan diets among individuals who consume them. |

| Plate and the Planet | Lancet Planet Health 6 7 :e—e Article Google Scholar Fanzo J et apprkach The importance Sustianable Maca root for mens health systems and the environment for Dietaryy. Wang JJ, Jing Sutsainable, Zhang Anxiety reduction techniques, Repairing damaged skin JH. Greenhouse gas emissions of self-selected individual diets in France: changing the diet structure or consuming less? The diet is often associated with countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea, including Spain, France, Italy, Greece, Turkey, Northern Africa, Middle Eastern, and Balkan countries. Malik VS et al Dietary protein intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in US men and women. Allied Health Professions. |

| Support The Nutrition Source | Kendall CW, Esfahani A, Sustainable dietary approach DJ The Anxiety reduction techniques between dietary apptoach and human health. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 47 12 —33 Article Sutsainable Scholar Sustainablw J Fueling workouts with food al The Maca root for mens health of plant-based diet with appfoach disease and mortality: a meta-analysis and systematic review of Prospect Cohort Studies. Towards better representation of organic agriculture in life cycle assessment. Gazan RBarré TPerignon Met al. This is primarily caused by the emission of Green-house gases, such as carbon emitted when using energy. If a person is looking to make more sustainable changes to the way they eat, they should consider these steps. txt Medlars, RefWorks Download citation. |

| Sustainable diet: Facts, nutrition, and more | Author contributions. JAMA Intern Stimulant-free energy supplement 4 — Learn more here. In the meantime, Susrainable ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript. Whole Grains At-A-Glance. The framework was finalized into five domains and concepts within those domains. |

| Sustainable diet: Everything you need to know | Tzonou A et al Dietary iron and coronary heart disease risk: a study from Greece. Am J Epidemiol 2 — Casiglia E et al Dietary iron intake and cardiovascular outcome in Italian women: year follow-up. J Womens Health 20 10 — Qi L et al Heme iron from diet as a risk factor for coronary heart disease in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 30 1 — Zhang W et al Associations of dietary iron intake with mortality from cardiovascular disease: the JACC study. J Epidemiol 22 6 — Tiedge M et al Relation between antioxidant enzyme gene expression and antioxidative defense status of insulin-producing cells. Diabetes 46 11 — Swaminathan S et al The role of iron in diabetes and its complications. Diabetes Care 30 7 — Wilson JG et al Potential role of increased iron stores in diabetes. Am J Med Sci 6 — Andrews NC Disorders of iron metabolism. N Engl J Med 26 — Kleinbongard P et al Plasma nitrite concentrations reflect the degree of endothelial dysfunction in humans. Free Radical Biol Med 40 2 — Männistö S et al High processed meat consumption is a risk factor of type 2 diabetes in the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention study. Br J Nutr 12 — Micha R, Wallace SK, Mozaffarian D Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation 21 — He FJ, Li J, MacGregor GA Effect of longer term modest salt reduction on blood pressure: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Förstermann U Oxidative stress in vascular disease: causes, defense mechanisms and potential therapies. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 5 6 — McGrowder D, Ragoobirsingh D, Dasgupta T Effects of S-nitroso-N-acetyl-penicillamine administration on glucose tolerance and plasma levels of insulin and glucagon in the dog. Nitric Oxide 5 4 — Rather IA et al The sources of chemical contaminants in food and their health implications. Front Pharmacol. Aktar W, Sengupta D, Chowdhury A Impact of pesticides use in agriculture: their benefits and hazards. Interdiscip Toxicol 2 1 :1— Mnif W et al Effect of endocrine disruptor pesticides: a review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 8 6 — Zuk AM et al Examining environmental contaminant mixtures among adults with type 2 diabetes in the Cree First Nation communities of Eeyou Istchee. Canada Sci Rep. Murray CJL et al Global burden of 87 risk factors in countries and territories, — a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study Burkart K et al Estimates, trends, and drivers of the global burden of type 2 diabetes attributable to PM2·5 air pollution, — an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Disease Study Lancet Planet Health 6 7 :e—e Fanzo J et al The importance of food systems and the environment for nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr 1 :7— Xu R et al Association between heat exposure and hospitalization for diabetes in Brazil during — a nationwide case-crossover study. Environ Health Perspect 11 Semenza JC et al Excess hospital admissions during the July heat wave in Chicago. Am J Prev Med 16 4 — Lee DC et al Acute post-disaster medical needs of patients with diabetes: emergency department use in New York City by diabetic adults after Hurricane Sandy. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 4 1 :e Diabetol Int 10 3 — Download references. Jarvis and V. Malik designed the manuscript; S. Jarvis wrote the initial draft and V. Malik had primary responsibility for the final content. Jarvis is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research SMART Healthy Cities Training Platform Award. Department of Nutritional Sciences, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. Department of Nutrition, Harvard T. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. Correspondence to Vasanti S. Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Springer Nature or its licensor e. a society or other partner holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author s or other rightsholder s ; author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law. Reprints and permissions. Jarvis, S. Healthy and Environmentally Sustainable Dietary Patterns for Type 2 Diabetes: Dietary Approaches as Co-benefits to the Overlapping Crises. J Indian Inst Sci , — Download citation. Received : 12 December Accepted : 14 January Published : 01 March Issue Date : January Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:. Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. Abstract The overlapping crises of type 2 diabetes T2D and climate change are two of the greatest challenges facing our global population. Access this article Log in via an institution. Data availability No new datasets were generated in this review. References Sun H et al IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for and projections for Diabetes Res Clin Pract Article Google Scholar Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition Food systems and diets: facing the challenges of the 21st century. London, UK Tubiello FN et al Greenhouse gas emissions from food systems: building the evidence base. Environ Res Lett 16 6 Article CAS Google Scholar Parris K et al Sustainable management of water resources in agriculture. l Article Google Scholar Springmann M et al Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change cobenefits of dietary change. Proc Natl Acad Sci 15 — Article CAS Google Scholar Springmann M et al Health and nutritional aspects of sustainable diet strategies and their association with environmental impacts: a global modelling analysis with country-level detail. Lancet Planet Health 2 10 :e—e Article Google Scholar Malik VS, Willett WC, Hu FB Global obesity: trends, risk factors and policy implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol 9 1 —27 Article Google Scholar Fao, et al. Am J Clin Nutr 3 — Article Google Scholar Cacau LT et al Development and validation of an index based on EAT-lancet recommendations: the planetary health diet index. Nutrients 13 5 Article Google Scholar Marchioni DM et al Low adherence to the EAT-lancet sustainable reference diet in the brazilian population: findings from the national dietary survey — Nutrients 14 6 Article Google Scholar Knuppel A et al EAT-Lancet score and major health outcomes: the EPIC-Oxford study. Lancet — Article Google Scholar Ibsen DB et al Adherence to the EAT-lancet diet and risk of stroke and stroke subtypes: a cohort study. Stroke 53 1 — Article Google Scholar Xu C et al Association between the EAT-lancet diet pattern and risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Nutrients 13 1 Article Google Scholar Lazarova SV, Sutherland JM, Jessri M Adherence to emerging plant-based dietary patterns and its association with cardiovascular disease risk in a nationally representative sample of Canadian adults. Am J Clin Nutr 1 —73 Article Google Scholar Harcombe Z This is not the EAT—Lancet Diet. The Lancet — Article Google Scholar Cacau LT et al Adherence to the planetary health diet index and obesity indicators in the brazilian longitudinal study of adult health ELSA-Brasil. N Engl J Med 19 — Article CAS Google Scholar Jenkins DJA et al Low-carbohydrate vegan diets in diabetes for weight loss and sustainability: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 5 — Article Google Scholar Gardner CD et al Effect of low-fat vs low-carbohydrate diet on month weight loss in overweight adults and the association with genotype pattern or insulin secretion: the DIETFITS randomized clinical trial. Circulation 11 :e—e Google Scholar Sievenpiper JL, Dworatzek PDN Food and dietary pattern-based recommendations: an emerging approach to clinical practice guidelines for nutrition therapy in diabetes. Can J Diabetes 37 1 —57 Article Google Scholar Abete I et al Association between total, processed, red and white meat consumption and all-cause, CVD and IHD mortality: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br J Nutr 5 — Article CAS Google Scholar Aune D et al Whole grain consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all cause and cause specific mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. i Article Google Scholar Bao Y et al Association of nut consumption with total and cause-specific mortality. N Engl J Med 21 — Article CAS Google Scholar Djousse L et al Egg consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in men and women. Diabetes Care 32 2 — Article Google Scholar Cooper AJ et al Fruit and vegetable intake and type 2 diabetes: EPIC-InterAct prospective study and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr 66 10 — Article CAS Google Scholar Jiang R Nut and peanut butter consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. JAMA 20 Article Google Scholar Schwingshackl L et al Food groups and risk of all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetes Care 35 7 — Article Google Scholar Marsh K, Zeuschner C, Saunders A Health implications of a vegetarian diet. Am J Lifestyle Med 6 3 — Article Google Scholar Yokoyama Y et al Vegetarian diets and blood pressure: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 4 — Article Google Scholar Dinu M et al Vegetarian, vegan diets and multiple health outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 57 17 — Article Google Scholar Tonstad S et al Type of vegetarian diet, body weight, and prevalence of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 32 5 — Article Google Scholar Qian F et al Association between plant-based dietary patterns and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 10 — Article Google Scholar Yokoyama Y et al Vegetarian diets and glycemic control in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 4 5 — Google Scholar Schwingshackl L, Bogensberger B, Hoffmann G Diet quality as assessed by the healthy eating index, alternate healthy eating index, dietary approaches to stop hypertension score, and health outcomes: an updated systematic review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. e11 Article Google Scholar Schwingshackl L et al Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and risk of diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pub Health Nutr 18 7 — Article Google Scholar Ley SH et al Changes in overall diet quality and subsequent type 2 diabetes risk: three us prospective cohorts. Diabetes Care 39 11 — Article CAS Google Scholar Chiuve SE et al Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease. J Nutr 6 — Article CAS Google Scholar Esfandiar Z et al Diet quality indices and the risk of type 2 diabetes in the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 10 5 :e Article Google Scholar Xu Z et al Diet quality, change in diet quality and risk of incident CVD and diabetes. Pub Health Nutr 23 2 — Article Google Scholar Galbete C et al Nordic diet, Mediterranean diet, and the risk of chronic diseases: the EPIC-Potsdam study. BMC Med 16 1 :1—13 Article Google Scholar De Oliveira Otto MC et al Everything in moderation-dietary diversity and quality, central obesity and risk of diabetes. PLoS ONE 10 10 :e Article Google Scholar InterAct Consortium kroeger dife, d Adherence to predefined dietary patterns and incident type 2 diabetes in European populations: EPIC-InterAct Study. Diabetologia — Article Google Scholar The InterAct C Mediterranean diet and type 2 diabetes risk in the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition EPIC Study: The InterAct project. Diabetes Care 34 9 — Article Google Scholar Feskens EJM, Sluik D, van Woudenbergh GJ Meat consumption, diabetes, and its complications. Curr DiabRep 13 2 — CAS Google Scholar Satija A et al Plant-based dietary patterns and incidence of type 2 diabetes in US men and women: results from Three Prospective Cohort Studies. PLoS Med 13 6 :1—18 Article Google Scholar Martínez-González MA et al A provegetarian food pattern and reduction in total mortality in the Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea PREDIMED study. Estruch R Salas-Salvado J, Corella D, Fito M, Aros F, Aldamiz M, Alonso A, Berjon J, Forga L, Gallego J, Garcia Layana MA, Larrauri A, Portu J, Timiraus J, Serrano-Martinez M, Martinez-Gonzalez M A, Editor Article Google Scholar Fresan U et al Global sustainability health, environment and monetary costs of three dietary patterns: results from a Spanish cohort the SUN project. BMJ Open 9 2 :e Article Google Scholar Chen Z et al Plant versus animal based diets and insulin resistance, prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: the Rotterdam Study. Springer, Netherlands, pp — Google Scholar Chen G-C et al Diet quality indices and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: The Singapore Chinese Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 12 — Article Google Scholar Chen Z et al Plant-based diet and adiposity over time in a middle-aged and elderly population: The Rotterdam Study. Epidemiology 30 2 — Article Google Scholar Satija A et al Changes in intake of plant-based diets and weight change: results from 3 prospective cohort studies. Nutrients 11 7 Article CAS Google Scholar Chen Z et al Changes in plant-based diet indices and subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes in women and men: Three U. Diabetes Care 44 3 — Article CAS Google Scholar Temme EH et al Greenhouse gas emission of diets in the Netherlands and associations with food, energy and macronutrient intakes. Pub Health Nutr 18 13 — Article Google Scholar Monsivais P et al Greater accordance with the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension dietary pattern is associated with lower diet-related greenhouse gas production but higher dietary costs in the United Kingdom. Am J Clin Nutr 1 — Article CAS Google Scholar Aston LM, Smith JN, Powles JW Impact of a reduced red and processed meat dietary pattern on disease risks and greenhouse gas emissions in the UK: a modelling study. BMJ Open 2 5 :e Article Google Scholar Soret S et al Climate change mitigation and health effects of varied dietary patterns in real-life settings throughout North America. Am J Clin Nutrn 1 SS Article CAS Google Scholar Scarborough P et al Dietary greenhouse gas emissions of meat-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians and vegans in the UK. Clim Change 2 — Article CAS Google Scholar van Dooren C et al Exploring dietary guidelines based on ecological and nutritional values: A comparison of six dietary patterns. Food Policy —46 Article Google Scholar Conrad Z, Blackstone NT, Roy ED Healthy diets can create environmental trade-offs, depending on how diet quality is measured. Lancet Planet Health 6 11 :e—e Article Google Scholar Blackstone NT et al Linking sustainability to the healthy eating patterns of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans: a modelling study. Lancet Planet Health 2 8 :e—e Article Google Scholar Jarvis SE, Nguyen M, Malik VS Association between adherence to plant-based dietary patterns and obesity risk: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 47 12 —33 Article Google Scholar Quek J et al The association of plant-based diet with cardiovascular disease and mortality: a meta-analysis and systematic review of Prospect Cohort Studies. The Lancet — Article Google Scholar da Costa Louzada ML et al The share of ultra-processed foods determines the overall nutritional quality of diets in Brazil. Public Health Nutr 21 1 — Article Google Scholar Martínez Steele E et al The share of ultra-processed foods and the overall nutritional quality of diets in the US: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. Popul Health Metrics 15 1 :1—11 Article Google Scholar Moubarac J-C et al Consumption of ultra-processed foods predicts diet quality in Canada. The Swedish dietary guidelines: find your way to eat greener, not too much and be active. The Swedish Food Agency. Uppsala; Territorial emissions and uptake of greenhouse gases. Accessed 15 Mar Macdiarmid JI, Kyle J, Horgan GW, Loe J, Fyfe C, Johnstone A, et al. Sustainable diets for the future: can we contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by eating a healthy diet? Reynolds CJ, Horgan GW, Whybrow S, Macdiarmid JI. Healthy and sustainable diets that meet greenhouse gas emission reduction targets and are affordable for different income groups in the UK. Future-proof and sustainable healthy diets based on current eating patterns in the Netherlands. Vieux F, Perignon M, Gazan R, Darmon N. Dietary changes needed to improve diet sustainability: are they similar across Europe? Eur J Clin Nutr. Brink E, van Rossum C, Postma-Smeets A, Stafleu A, Wolvers D, van Dooren C, et al. Development of healthy and sustainable food-based dietary guidelines for the Netherlands. Green R, Milner J, Dangour AD, Haines A, Chalabi Z, Markandya A, et al. The potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the UK through healthy and realistic dietary change. Clim Change. Eustachio Colombo P, Elinder LS, Lindroos AK, Parlesak A. Designing nutritionally adequate and climate-friendly diets for omnivorous, pescatarian, vegetarian and vegan adolescents in sweden using linear optimization. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Verly-Jr E, de Carvalho AM, Marchioni DML, Darmon N. The cost of eating more sustainable diets: A nutritional and environmental diet optimisation study. Glob Public Health. Maillot M, Drewnowski A. Energy allowances for solid fats and added sugars in nutritionally adequate U. Nykanen E-PA, Dunning HE, Aryeetey RNO, Robertson A, Parlesak A. Nutritionally optimized, culturally acceptable, cost-minimized diets for low income ghanaian families using linear programming. Barosh L, Friel S, Engelhardt K, Chan L. The cost of a healthy and sustainable diet — who can afford it? Aust N Z J Public Health. Springmann M, Clark MA, Rayner M, Scarborough P, Webb P. The global and regional costs of healthy and sustainable dietary patterns: a modelling study. Beal T, Ortenzi F, Fanzo J. Estimated micronutrient shortfalls of the EAT—Lancet planetary health diet. Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Aleksandrowicz L, Green R, Joy EJM, Smith P, Haines A. The impacts of dietary change on greenhouse gas emissions, land use, water use, and health: a systematic review. Franco D, Martins AJ, López-Pedrouso M, Purriños L, Cerqueira MA, Vicente AA, et al. Strategy towards replacing pork backfat with a linseed oleogel in Frankfurter sausages and its evaluation on physicochemical, nutritional, and sensory characteristics. Heck RT, Fagundes MB, Cichoski AJ, de Menezes CR, Barin JS, Lorenzo JM, et al. Meat Sci. Lag om etikprövning av forskning som avser människor SFS [Law on ethical review of research concerning humans SFS ]. Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet; Download references. The contribution by all authors was funded by the Swedish Research Council FORMAS grant number The funder had no role in the study design, data analysis or writing, or the decision to submit for publication. Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. Department of Global Public Health, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden. Patricia Eustachio Colombo, Liselotte Schäfer Elinder, Esa-Pekka A. Centre on Climate Change and Planetary Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, WC1E 7HT, London, UK. Centre for Epidemiology and Community Medicine, Region Stockholm, Stockholm, Sweden. Functional Foods Forum, University of Turku, Turku, Finland. Department of Internal Medicine and Clinical Nutrition, the Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden. Department of Nutrition, Exercise and Sports, Copenhagen University, Copenhagen, Denmark. Personalized Nutrition, Duale Hochschule Baden-Württemberg, Heilbronn, Germany. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. PEC contributed to the conceptualisation and design of the study, the data analysis, presentation, interpretation of the results, as well as drafted and edited the manuscript. LSE contributed to the conceptualisation and design of the study, and to the critical revising of the manuscript. EPN contributed to the conceptualisation and design of the study, data curation, and to the critical revising of the manuscript. EP contributed to the conceptualisation and design of the study, and to the critical revising of the manuscript. AKL provided data, contributed to the conceptualisation and design of the study, and to the critical revising of the manuscript. AP maintained study oversight, contributed to the conceptualisation and design of the study, and to the critical revising of the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. All authors approved the final article version to be submitted. Correspondence to Patricia Eustachio Colombo. Ethical approval for the original Riksmaten vuxna —11 dietary survey was granted by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala. This data is now fully anonymized and publicly available and so the current study involved no personal data. Ethical approval was therefore not required for this study in accordance with Swedish law [ 53 ]. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. Reprints and permissions. Eustachio Colombo, P. et al. Developing a novel optimisation approach for keeping heterogeneous diets healthy and within planetary boundaries for climate change. Eur J Clin Nutr Download citation. Received : 10 January Revised : 02 November Accepted : 08 November Published : 21 November Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:. Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. Skip to main content Thank you for visiting nature. nature european journal of clinical nutrition articles article. Download PDF. Subjects Malnutrition Risk factors. Abstract Background and objectives Current dietary habits have substantial negative impacts on the health of people and the planet. Results Three dietary clusters were identified. Conclusions The novel cluster-based optimisation approach was able to generate alternatives that may be more acceptable and realistic for a sustainable diet across different groups in the population. Introduction Contemporary diets in high and middle income countries are major contributors to the burden of chronic diseases as well as to the rapidly accelerating climate crisis [ 1 ]. Materials and methods Study design and dietary data This was a modelling study combining hierarchical clustering analysis with linear programming to design nutritionally adequate, health-promoting, climate-friendly and culturally acceptable diets. Nutritional composition Energy and nutrient intakes of the edible parts of foods as eaten e. Grouping of foods For analytical and descriptive purposes, foods were grouped in 24 food categories, based on the categorisations used in the RISE Climate Database: Red meat including red meat dishes ; Processed meat both red meat and poultry ; Poultry including poultry based dishes ; Seafood including fish, mussels and crabs, and seafood dishes ; Offal; Dairy e. Cluster analysis Clusters analysis was performed to identify dominating eating patterns in the Swedish population. Optimisation The chosen optimisation method of LP has successfully been applied to optimise goal determinants of diets while considering a multitude of sometimes conflicting constraints [ 6 , 29 ]. Table 1 Characteristics of all applied models. Full size table. Results Identifying prevalent dietary clusters The cluster analysis resulted in three diet clusters roughly balanced in size , and individuals in clusters 1, 2 and 3 respectively. Full size image. Discussion In this study we demonstrated that the combination of cluster analysis with linear optimisation can provide guidance to nutritionally adequate, health-promoting, affordable and climate-friendly diets for different self-selected dietary patterns for the Swedish Population. Data availability Data can be found within the published article and its supplementary files. References Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B, et al. Article PubMed Google Scholar Government Offices of Sweden. Article Google Scholar Béné C, Fanzo J, Haddad L, Hawkes C, Caron P, Vermeulen S, et al. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Gazan R, Brouzes CMC, Vieux F, Maillot M, Lluch A, Darmon N. Article PubMed Google Scholar Perignon M, Masset G, Ferrari G, Barré T, Vieux F, Maillot M, et al. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Milner J, Green R, Dangour AD, Haines A, Chalabi Z, Spadaro J, et al. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Eustachio Colombo P, Patterson E, Elinder LS, Lindroos AK, Sonesson U, Darmon N, et al. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Darmon N, Ferguson EL, Briend A. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Horgan GW, Perrin A, Whybrow S, Macdiarmid JI. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Maillot M, Vieux F, Amiot MJ, Darmon N. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Lluch A, Maillot M, Gazan R, Vieux F, Delaere F, Vaudaine S, et al. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Cocking C, Walton J, Kehoe L, Cashman KD, Flynn A. Article PubMed Google Scholar Gibbons H, Carr E, McNulty BA, Nugent AP, Walton J, Flynn A, et al. Article Google Scholar World Wildlife Fund. Google Scholar International Organization for Standardization. Google Scholar Charrad M, Ghazzali N, Boiteau V. Article Google Scholar R Core Team. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Parlesak A, Tetens I, Dejgard Jensen J, Smed S, Gabrijelcic Blenkus M, Rayner M, et al. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Dantzig GB Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Reynolds CJ, Horgan GW, Whybrow S, Macdiarmid JI. Article Google Scholar Vieux F, Perignon M, Gazan R, Darmon N. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Brink E, van Rossum C, Postma-Smeets A, Stafleu A, Wolvers D, van Dooren C, et al. Figure 9. It is observed from Figure 9 that a shift to sustainable diet concepts such as Vegetarian and Vegan diet would reduce the total GHGE, land use, water consumption, and energy use by Furthermore, we observe a relative closeness in results due to the similar due to similar product composition that exists between the two diet concepts. Likewise, for health risk reduction, we observe that adherence to the Vegetarian and Vegan diet reduces the risk to diabetes, total mortality, heart diseases, obesity, and total cancer by Shifting to other diet concepts such as the Mediterranean diet and the healthy US-style diet, we observe a relatively lower reduction compared to other diet concepts. One of the surprising findings of the study was, adopting the U. These results corroborate strongly with the studies of 46 , who found a relative increase in GHGE from U. diet style. It is important to mention that the results presented here are average values Life Cycle Assessment L. A studies on the selected diet concepts in the United States. The data collected for each diet pattern are isocaloric equivalent in total calories. Using the results obtained in sections Weight of criteria and Health and Environmental impact evaluation results, we ranked the diet concepts using the integrated AHP-TOPSIS decision model. From Figure 10 , the Vegetarian, Vegan, and Provegetarian diets ranked first, second, and third, with a performance score of 0. This is somewhat surprising as the vegan diet appears to have a better environmental impact reduction as compared to the vegetarian diet concept see Section Health and Environmental impact evaluation results. On the contrary, the vegetarian diet has higher health impact reductions for some indicators as compared to the vegan diet concept. From a socioeconomic perspective, the vegetarian diet concept has a slightly higher reduction than the vegan diet. However, the model adopted for the evaluation takes into consideration the criteria weights presented in Section Weight of criteria. To wit, we observe from Figure 8 that higher weights were allocated to health indicators as compared to environmental and socio-economic indicators. Consequently, influencing the overall performance score and ranking of vegetarian and vegan diet concepts. The results imply that adopting and national-wide implementation of different vegetarian diet concepts can substantially reduce diets' environmental and health impacts. Our results corroborate strongly with previous research of 8 , 9 , 15 , who illustrated that the adoption of diets higher in plant-based than animal-based foods against the national Healthy US-style diet pattern would benefit the environment and the population's health. Furthermore, the results further reinforce previous research on the impact of diet on the environment and suggest that Vegetarian, Vegan, and Provegeterian diet pattern has the most sustainable impact on U. Despite these benefits, several bottlenecks and challenges exist that hinder the successful adoption of these concepts in America. The following Section explores different challenges, provides recommendations, and proposes a dynamic methodological framework to ensure a sustainable food system. So far, we have assessed which health, environmental and socio-economic factors are relevant to consumers, evaluated nine distinct sustainable diet concepts using sustainability metrics, and ranked these concepts to identify the optimal diet concept. Nonetheless, several challenges hinder the adoption and implementation of these sustainable diet concept. This Section identifies the bottlenecks in implementing different sustainable diet concepts and presents recommendations to rebuild a resilient and sustainable food system. Table 5 summarizes the challenges associated with adopting candidate sustainable diet concepts. From Table 5 , it is clear that widening the adoption of the sustainable diet concept presents a challenge, thus the need to understand the synergies in socio-economic, demographic, health, and environmental priorities. Sustainable diet concepts interact with consumer preference and wide array of social, economic and environmental systems, thus presenting a complex interaction driven by multiple factors. More importantly, a lack of information flow between the different actors and their respective systems exacerbate these shortcomings. Additional, knowledge on the trade-offs at varying Spatio-temporal scales is required; thus, we propose a conceptual system thinking approach for effective implementation of need. Figure 11 presents the conceptual framework that illustrates a holistic representation of sustainable diet concepts and their interconnections between actors, bottlenecks, components and different sub-systems. The elements in conceptual framework interact dynamically to give rise to predictable health, environmental and socio-economic impacts. The framework argues for a better and holistic integration of bottlenecks such as lack of knowledge and feedback across the interactions between the different components of the system and actors. Also, the framework argues for transparent sharing of information among actors to develop an optimized sustainable diet. Figure A system thinking approach to address the challenges of scaling up sustainable diet concepts to an optimized diet concept. Application of system thinking and related tools can be found in different fields such energy, financial sectors and policy making. Increasingly, these different fields recognize the necessity of system thinking approaches to addressing today's interconnected challenges. Thus, the authors argue that the adoption of system thinking and related tools can help all actors of sustainable diet concepts to better plan for future interventions and wide adoption among consumers. Furthermore, policies can be enacted to introduce sustainable diet concepts to the population at an early childhood stage. It could be integrated into curriculums during early childhood education. Multi-sectoral efforts and campaigns from public organizations, local authorities, government, and non-governmental institutions to raise public awareness on the enormous benefits of sustainable diets will be paramount. Therefore, the proposed system thinking approach seeks to navigate stakeholders in implementation sustainable diet concepts toward a more comprehensive and broader picture by considering all interconnected factors to achieve a systemic change. The novel framework also suggests that optimized sustainable diet concepts that take into consideration multiple conflicting objectives as well their trade-offs have the potential to address the diet- health-environment trilemma. One major limitation of this study is that the authors observed a moderate variability in life cycle assessment results despite considering similar diet concepts. These may be attributed to the choice of parameters, the definition of system boundaries, the decision of function units, and the uncertainty evaluation adopted during the assessment. More disturbingly, most of these life cycle assessment studies do not account for the type of agroecology which may improve the environmental outcomes. The present study set out to evaluate the effectiveness of the implementation of sustainable healthy diet concepts in the United States. The study also examined the relationship between sustainable diet concepts and key factors that lead to improvement in human health, reductions in environmental damage and socio-economic benefits. Additionally, the AHP framework applied by the authors, provided an opportunity to curate expert opinions on which environmental-health-socio-economic indicators were of outermost relevance when considering resource allocation to optimize the adoption of sustainable diet concepts. The findings indicate that health indicators such as risk to mortality and cardiovascular disease are highly prioritized compared to other socio-economic, and environmental indicators. Through the application of mathematical modeling AHP-TOPSIS and a set of environmental, health and socio-economic indicators, vegetarian, vegan and provegetarian diet concepts ranked first, second and third, respectively. However, the implementation and wider adoption of sustainable diet concepts is hindered by intrinsic socio-economic, cultural and behavioral barriers. These include a lack of understanding, limited access to food ingredients, and unfamiliarity with sustainable diet menus. Hence, the study proposed a novel conceptual system thinking framework to sustainable diet concepts, which takes into consideration these bottlenecks prior to implementation sustainable diets on larger scale. The proposed can potentially optimize sustainable diet acceptance by consumers and offset different health, environmental and socio-economic impacts. The novel framework shows the complex interactions and dynamics between diet concepts, social cultural challenges, food environment, key stakeholders and multiple subsystems. Taken together, it provides a holistic representation of optimizing sustainable diet initiatives and adoption among consumers. It would be interesting to assess the effectiveness of the conceptual system thinking approach through a practical application of system dynamic models, then translate the results through an intervention case study. PA: conceptualization, investigation and expert survey, methodology, data curation, writing initial draft , and data visualization. EK: conceptualization, investigation and survey, resources, writing review and editing , and supervision. JB: conceptualization, methodology, and writing review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version. This project was funded by the Graduate Professional Student Congress Tiffany Marcantonio Research Grant at the University of Arkansas and Department of Biological and Agricutural Engineering, University of Arkansas. The authors are grateful to the Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering Department and the Department of Food Science for supporting the work. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher. Garnett T. Where are the best opportunities for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the food system including the food chain?. Food Policy. doi: CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Phan K, Kothari P, Lee NJ, Virk S, Kim JS, Cho SK. Impact of obesity on outcomes in adults undergoing elective posterior cervical fusion. PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Phillips JA. Dietary guidelines for Americans, — Workplace Health Saf. CDC A. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chicago Google Scholar. Chai BC, van der Voort JR, Grofelnik K, Eliasdottir HG, Klöss I, Perez-Cueto FJ. Which diet has the least environmental impact on our planet? A systematic review of vegan, vegetarian and omnivorous diets. Domingo NG, Balasubramanian S, Thakrar SK, Clark MA, Adams PJ, Marshall JD, et al. Air quality—related health damages of food. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B, Springmann M, Lang T, Vermeulen S, et al. Food in the anthropocene: the EAT—Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Burlingame B, Dernini S. Biodiversity and Sustainable Diets United Against Hunger 3—5 November Rome: FAO Headquarters Agyemang P, Kwofie EM. Response-to-failure analysis of global food system initiatives: a resilience perspective. Front Sustain Food Syst. Reinhardt SL, Boehm R, Blackstone NT, El-Abbadi NH, McNally Brandow JS, Taylor SF, et al. Systematic review of dietary patterns and sustainability in the United States. Adv Nutr. Mekonnen MM, Fulton J. The effect of diet changes and food loss reduction in reducing the water footprint of an average American. Water Int. Orlich MJ, Singh PN, Sabaté J, Jaceldo-Siegl K, Fan J, Knutsen S, et al. Vegetarian dietary patterns and mortality in Adventist Health Study 2. JAMA Intern Med. Springmann M, Clark MA, Rayner M, Scarborough P, Webb P. The global and regional costs of healthy and sustainable dietary patterns: a modelling study. Lancet Planetary Health. Fresán U, Martínez-González MA, Sabaté J, Bes-Rastrollo M. Global sustainability health, environment and monetary costs of three dietary patterns: Results from a Spanish cohort the SUN project. BMJ Open. Blackstone NT, El-Abbadi NH, McCabe MS, Griffin TS, Nelson ME. Linking sustainability to the healthy eating patterns of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans: a modelling study. Lancet Planet Health. Aleksandrowicz L, Green R, Joy EJ, Smith P, Haines A. The impacts of dietary change on greenhouse gas emissions, land use, water use, and health: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. Schwingshackl L, Missbach B, König J, Hoffmann G. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and risk of diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. Zhong X, Guo L, Zhang L, Li Y, He R, Cheng G. Inflammatory potential of diet and risk of cardiovascular disease or mortality: A meta-analysis. Sci Rep. Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM, Miller PE, Liese AD, Kahle LL, Park Y, et al. Higher diet quality is associated with decreased risk of all-cause, cardiovascular disease, and cancer mortality among older adults. J Nutr. Behrens G, Gredner T, Stock C, Leitzmann MF, Brenner H, Mons U. Cancers due to excess weight, LOW physical activity, and unhealthy diet: Estimation of the attributable cancer burden in Germany. Deutsches Ärzteblatt Int. Clark M, Hill J, Tilman D. The diet, health, and environment trilemma. Annu Rev Environ Resour. Röös E, Carlsson G, Ferawati F, Hefni M, Stephan A, Tidåker P, et al. Less meat, more legumes: prospects and challenges in the transition toward sustainable diets in Sweden. Renew Agric Food Syst. Macdiarmid JI, Kyle J, Horgan GW, Loe J, Fyfe C, Johnstone A, et al. Sustainable diets for the future: can we contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by eating a healthy diet? Am J Clin Nutr. Lewis M, McNaughton SA, Rychetnik L, Lee AJ. Cost and affordability of healthy, equitable and sustainable diets in low socioeconomic groups in Australia. Ritchie H, Roser M. Environmental Impacts of Food Production. Cambridge, MA: Our World in Data Food and Agricultural data. Clark MA, Springmann M, Hill J, Tilman D. Multiple health and environmental impacts of foods. Johnston JL, Fanzo JC, Cogill B. Understanding sustainable diets: a descriptive analysis of the determinants and processes that influence diets and their impact on health, food security, and environmental sustainability. Wang JJ, Jing YY, Zhang CF, Zhao JH. Review on multi-criteria decision analysis aid in sustainable energy decision-making. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. Neba FA, Agyemang P, Ndam YD, Emmanuel E, Ndip EG, Seidu R. Leveraging integrated model-based approaches to unlock bioenergy potentials in enhancing green energy and environment. |

Sustainable dietary approach -

A main advantage of the approach exploring sustainable diets based on the analysis of hypothetical diets ie, approach 1 is that it does not require data on individual food consumption, or on food characteristics of detailed food items. Moreover, results from this approach are generally straightforward and easy to understand, hence more suitable for dissemination.

This approach is thus still very widespread see, eg, Kim et al 22 , although it has many limitations. An obvious drawback of these studies is that they are based on predetermined assumptions concerning the food content of a sustainable diet. Therefore, they do not allow the investigation of other possible not envisaged a priori diets that could be similarly, or even more, sustainable.

A main limitation of this approach based on theoretical scenarios is that the sustainability of the proposed diets cannot be completely ensured, because the sustainability criteria are verified a posteriori, the composition of the diets having been defined prior to the sustainability assessment.

Hence, the nutrient content and the environmental impacts of such hypothetical diets are not necessarily improved and may even deteriorate for some indicators. For instance, some diets presented as sustainable by the EAT- Lancet Commission are assumed to be healthy, notably the vegan version.