:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/surprising-psychological-benefits-of-music-4126866-Final-44c12600b86a4c71883710685fe13a7f.png)

Music therapy for depression -

Music therapy allows people a safe, calming atmosphere to explore their personal struggles and anxieties. In fact, many patients who receive musical therapy have no musical skills to begin with. Patients develop a sense of control over their struggles through the feeling of accomplishing a new task, or learning a new skill.

By gaining a feeling of control over their life, they feel more capable of making positive changes. Therefore, music therapy can be used to help anybody who is struggling from depression. The different types of music therapy that are used are known as receptive music therapy and active music therapy.

Receptive music therapy has also shown to be effective in easing anxiety issues in patients undergoing surgery. In active music therapy, the patients actually participate in the process of creating music.

This is typically done by having the patient learn to sing or play an instrument. Improvisation is often encouraged by the mental health professional in order to help the patient explore their feelings and emotions.

What makes all of this different from listening to an Ipod or going to a local piano teacher, is that the music chosen during receptive therapy, and the music performed during active music therapy, are specifically chosen by a therapist or psychiatrist trained in treating depression.

Research shows that both psychotherapy and prescription medication, are the most common treatments for depression. They are likely to improve when they are combined with music therapy. The overall findings have shown that patients noticeably report being less depressed when they receive music therapy in addition to their regular or ongoing treatment.

Now, research has turned to examining which types of music, and which types of music therapies, work best for different individuals and different ailments.

In the case of individuals suffering from depression, brain imaging scans have shown music therapy is effective in activating the portions of the brain that regulate emotional states.

The American Music Therapy Association provides ample studies that show a link between music therapy and treating depression and anxiety. While more research needs to be completed in order to fully understand why music therapy is beneficial, three main theories were hypothesized in The British Journal of Psychiatry.

The first theory is that the patient receives a sense of meaning and pleasure out of performing music. It allows those who have difficulty expressing their emotions an environment in which to engage in an expressive way, while simultaneously providing a pleasurable experience from performing or listening to music.

Additionally, active music therapy is theorized to treat depression because of the inherent physical nature that is involved in singing or playing an instrument. Through the combination of different breathing techniques, as well as the physical motion involved in strumming a guitar or playing a piano, the body is engaged in physical activity.

Even this light form of exercise is thought to combat feelings of depression and anxiety. Finally, music therapy is thought to be useful in combating depression because it allows the patient to communicate and interact with other people in a new or different way.

By changing the form of communication, the patient may feel more open or relaxed about sharing their emotions and other personal details with their therapists. Incadence is transforming the health care industry. By joining our team, you can be a part of this revolution and a leader in health care.

About Us FAQ Contact Us Who We Serve Blog. You Might Also Like Find Your Life Rhythm Through These 5 Life Coaching Techniques. Mental Health News. Promoting Positive Mental Health in the Workplace.

Music Therapy for Shelter Dogs. Navigating the Path to a Medical Degree. Music Therapy News. Music Therapy Across Cultures: How Music Reveals Universal Truths to Each of Us.

New York, New York, USA: Guilford Publications, Bruscia KE. Defining Music Therapy. University Park, Illinois, USA: Barcelona Publishers, London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishen.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ Clinical research ed ; : — Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis.

Statistics in medicine ; 21 11 : — Cochran WG. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics ; — View Article Google Scholar Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test.

Wu Q, Chen T, Wang Z, et al. Effectiveness of music therapy on improving treatment motivation and emotion in female patients with methamphetamine use disorder: A randomized controlled trial.

Subst Abus 1—8. Volpe U, Gianoglio C, Autiero L, et al. Acute Effects of Music Therapy in Subjects With Psychosis During Inpatient Treatment.

Psychiatry ; 81 3 : — Trimmer C, Tyo R, Pikard J, McKenna C, Naeem F. Low-Intensity Cognitive Behavioural Therapy-Based Music Group CBT-Music for the Treatment of Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression: A Feasibility Study.

Behav Cogn Psychother ; 46 2 : — Toccafondi A, Bonacchi A, Mambrini A, Miccinesi G, Prosseda R, Cantore M. Live music intervention for cancer inpatients: The Music Givers format.

Palliat Support Care ; 16 6 : — Sigurdardóttir GA, Nielsen PM, Rønager J, Wang AG. A pilot study on high amplitude low frequency-music impulse stimulation as an add-on treatment for depression. Brain Behav ; 9 10 : e Ribeiro MKA, Alcântara-Silva TRM, Oliveira JCM, et al.

Music therapy intervention in cardiac autonomic modulation, anxiety, and depression in mothers of preterms: randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychol ; 6 1 : Ploukou S, Panagopoulou E. Playing music improves well-being of oncology nurses. Appl Nurs Res ; 77— Pérez-Ros P, Cubero-Plazas L, Mejías-Serrano T, Cunha C, Martínez-Arnau FM.

Preferred Music Listening Intervention in Nursing Home Residents with Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Intervention Study. J Alzheimers Dis ; 70 2 : — Park S, Lee J-M, Baik Y, et al.

A Preliminary Study of the Effects of an Arts Education Program on Executive Function, Behavior, and Brain Structure in a Sample of Nonclinical School-Aged Children.

J Child Neurol ; 30 13 : — Mahendran R, Gandhi M, Moorakonda RB, et al. Art therapy is associated with sustained improvement in cognitive function in the elderly with mild neurocognitive disorder: findings from a pilot randomized controlled trial for art therapy and music reminiscence activity versus usual care.

Trials ; 19 1 : Low MY, Lacson C, Zhang F, Kesslick A, Bradt J. Vocal Music Therapy for Chronic Pain: A Mixed Methods Feasibility Study. J Altern Complement Med ; 26 2 : — Liao SJ, Tan MP, Chong MC, Chua YP. The Impact of Combined Music and Tai Chi on Depressive Symptoms Among Community-Dwelling Older Persons: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial.

Issues Ment Health Nurs ; 39 5 : — Liao SJ, Chong MC, Tan MP, Chua YP. Tai Chi with music improves quality of life among community-dwelling older persons with mild to moderate depressive symptoms: A cluster randomized controlled trial.

Geriatr Nurs ; 40 2 : —9. Hars M, Herrmann FR, Gold G, Rizzoli R, Trombetti A. Effect of music-based multitask training on cognition and mood in older adults.

Age Ageing ; 43 2 : — Hanser SB, Thompson LW. Effects of a music therapy strategy on depressed older adults.

J Gerontol ; 49 6 : P—P9. Guétin S, Portet F, Picot MC, et al. Effect of music therapy on anxiety and depression in patients with Alzheimer's type dementia: randomised, controlled study.

Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord ; 28 1 : 36— Gök Ugur H, Yaman Aktaş Y, Orak OS, Saglambilen O, Aydin Avci İ. The effect of music therapy on depression and physiological parameters in elderly people living in a Turkish nursing home: a randomized-controlled trial.

Aging Ment Health ; 21 12 : —6. Fancourt D, Warran K, Finn S, Wiseman T. Psychosocial singing interventions for the mental health and well-being of family carers of patients with cancer: results from a longitudinal controlled study.

BMJ Open ; 9 8 : e Erkkilä J, Punkanen M, Fachner J, et al. Individual music therapy for depression: randomised controlled trial.

Br J Psychiatry ; 2 : —9. Cooke M, Moyle W, Shum D, Harrison S, Murfield J. A randomized controlled trial exploring the effect of music on quality of life and depression in older people with dementia.

Journal of health psychology ; 15 5 : — Chu H, Yang C-Y, Lin Y, et al. The impact of group music therapy on depression and cognition in elderly persons with dementia: a randomized controlled study.

Biol Res Nurs ; 16 2 : — Choi AN, Lee MS, Lim HJ. Effects of group music intervention on depression, anxiety, and relationships in psychiatric patients: a pilot study. J Altern Complement Med ; 14 5 : — Chirico A, Maiorano P, Indovina P, et al.

Virtual reality and music therapy as distraction interventions to alleviate anxiety and improve mood states in breast cancer patients during chemotherapy. J Cell Physiol ; 6 : — Cheung AT, Li WHC, Ho KY, et al.

Efficacy of musical training on psychological outcomes and quality of life in Chinese pediatric brain tumor survivors. Psycho-oncology ; 28 1 : — Chen SC, Chou CC, Chang HJ, Lin MF. Comparison of group vs self-directed music interventions to reduce chemotherapy-related distress and cognitive appraisal: an exploratory study.

Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer ; 26 2 : —9. Chen CJ, Sung HC, Lee MS, Chang CY. The effects of Chinese five-element music therapy on nursing students with depressed mood.

Int J Nurs Pract ; 21 2 : —9. Chen CJ, Chen YC, Ho CS, Lee YC. Effects of preferred music therapy on peer attachment, depression, and salivary cortisol among early adolescents in Taiwan.

Journal of advanced nursing ; 75 9 : — Chan MF, Wong ZY, Onishi H, Thayala NV. Effects of music on depression in older people: a randomised controlled trial.

J Clin Nurs ; 21 5—6 : — Chan MF, Chan EA, Mok E, Kwan Tse FY. Effect of music on depression levels and physiological responses in community-based older adults. Int J Ment Health Nurs ; 18 4 : — Chan MF, Chan EA, Mok E.

Effects of music on depression and sleep quality in elderly people: A randomised controlled trial. Complement Ther Med ; 18 3—4 : —9. Burrai F, Sanna GD, Moccia E, et al. Beneficial Effects of Listening to Classical Music in Patients With Heart Failure: A Randomized Controlled Trial.

J Card Fail Burrai F, Lupi R, Luppi M, et al. Effects of Listening to Live Singing in Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis: A Randomized Controlled Crossover Study.

Biol Res Nurs ; 21 1 : 30—8. Biasutti M, Mangiacotti A. Music Training Improves Depressed Mood Symptoms in Elderly People: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Aging Hum Dev Zerhusen JD, Boyle K, Wilson W.

Out of the darkness: group cognitive therapy for depressed elderly. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv ; 29 9 : 16— Radulovic R. The using of music therapy in treatment of depressive disorders. Summary of Master Thesis. Belgrade: Faculty of Medicine University of Belgrade, Hendricks CB, Robinson B, Bradley B, Davis K.

Using music techniques to treat adolescent depression. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development ; 39— Hendricks CB. A study of the use of music therapy techniques in a group for the treatment of adolescent depression.

Dissertation Abstracts International ; 62 2-A : Albornoz Y. The effects of group improvisational music therapy on depression in adolescents and adults with substance abuse: a randomised controlled trial.

Nordic Journal of Music Therapy ; 20 3 : — Yap AF, Kwan YH, Tan CS, Ibrahim S, Ang SB. Rhythm-centred music making in community living elderly: a randomized pilot study. BMC complementary and alternative medicine ; 17 1 : Wang J, Wang H, Zhang D.

Impact of group music therapy on the depression mood of college students. Health ; 3: —5. Torres E, Pedersen IN, Pérez-Fernández JI. Randomized Trial of a Group Music and Imagery Method GrpMI for Women with Fibromyalgia.

J Music Ther ; 55 2 : — Raglio A, Giovanazzi E, Pain D, et al. Active music therapy approach in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a randomized-controlled trial. Int J Rehabil Res ; 39 4 : —7. Porter S, McConnell T, McLaughlin K, et al. Music therapy for children and adolescents with behavioural and emotional problems: a randomised controlled trial.

J Child Psychol Psychiatry ; 58 5 : — Nwebube C, Glover V, Stewart L. Prenatal listening to songs composed for pregnancy and symptoms of anxiety and depression: a pilot study. Mondanaro JF, Homel P, Lonner B, Shepp J, Lichtensztein M, Loewy JV.

Music Therapy Increases Comfort and Reduces Pain in Patients Recovering From Spine Surgery. Am J Orthop ; 46 1 : E13—E Lu SF, Lo C-HK, Sung HC, Hsieh TC, Yu SC, Chang SC. Effects of group music intervention on psychiatric symptoms and depression in patient with schizophrenia.

Complement Ther Med ; 21 6 : —8. Liao J, Wu Y, Zhao Y, et al. Progressive Muscle Relaxation Combined with Chinese Medicine Five-Element Music on Depression for Cancer Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Chin J Integr Med ; 24 5 : —7. Koelsch S, Offermanns K, Franzke P.

Music in the treatment of affective disorders: an exploratory investigation of a new method for music-therapeutic research. Music Percept Interdisc J ; — Harmat L, Takács J, Bódizs R. Music improves sleep quality in students. Journal of advanced nursing ; 62 3 : — Giovagnoli AR, Manfredi V, Parente A, Schifano L, Oliveri S, Avanzini G.

Cognitive training in Alzheimer's disease: a controlled randomized study. Neurological sciences: official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology ; 38 8 : — Fancourt D, Perkins R, Ascenso S, Carvalho LA, Steptoe A, Williamon A.

Effects of Group Drumming Interventions on Anxiety, Depression, Social Resilience and Inflammatory Immune Response among Mental Health Service Users. PLoS ONE ; 11 3 : e Esfandiari N, Mansouri S. The effect of listening to light and heavy music on reducing the symptoms of depression among female students.

Arts Psychother ; —3. Chen XJ, Hannibal N, Gold C. Randomized Trial of Group Music Therapy With Chinese Prisoners: Impact on Anxiety, Depression, and Self-Esteem.

Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol ; 60 9 : — Chen SC, Yeh ML, Chang HJ, Lin MF. Music, heart rate variability, and symptom clusters: a comparative study.

Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer ; 28 1 : — Chang MY, Chen CH, Huang KF. Effects of music therapy on psychological health of women during pregnancy.

J Clin Nurs ; 17 19 : —7. Yang WJ, Bai YM, Qin L, et al. The effectiveness of music therapy for postpartum depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Is music therapy an effective treatment for depression? Foe there Music therapy for depression between the various types deprression music therapy? Depression Herbal pick-me-up tonic a common problem marked by mood changes and loss of interest and pleasure in normal activities. Inan estimated Music affects a patient's emotional state by increasing dopaminergic activity, downregulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and stimulating the parasympathetic nervous system.Music therapy for depression -

While this study was not designed to look specifically at Anxiety Disorders, other studies have found music therapy to be an effective treatment for anxiety when used alongside standard therapies. One of the most important takeaways from this study is that music therapy can make a significant impact for many depressed patients when used alongside standard therapies.

Consistent with previous research, patients in this study were significantly more likely to at least partly recover from depression when they received music therapy.

While the study only looked at one type of music therapy, it would be interesting to see if music in general, both listening and playing, has any impact on depression. One possible weakness of this study was that the control patients did not receive the same amount of therapy as music therapy patients.

From this study design, we do not know whether it was the "music" that led to the improvements seen, or whether these improvements came from having more therapy overall. All in all, this study provides good support for what looks like a great therapeutic option for depressed patients.

The pandemic has magnified environmental and personality-based risk factors for Researchers are discovering associations between mental disorders and cancer. Coffee consumption is associated with a decreased risk of developing depression Depressed individuals are more likely to use cannabis than the general populatio Acupuncture has been shown to significantly improve hot flashes, sleep, and swea We've visualized the results of a new clinical trial that compared butter, cocon How long does COVID live on Plastic?

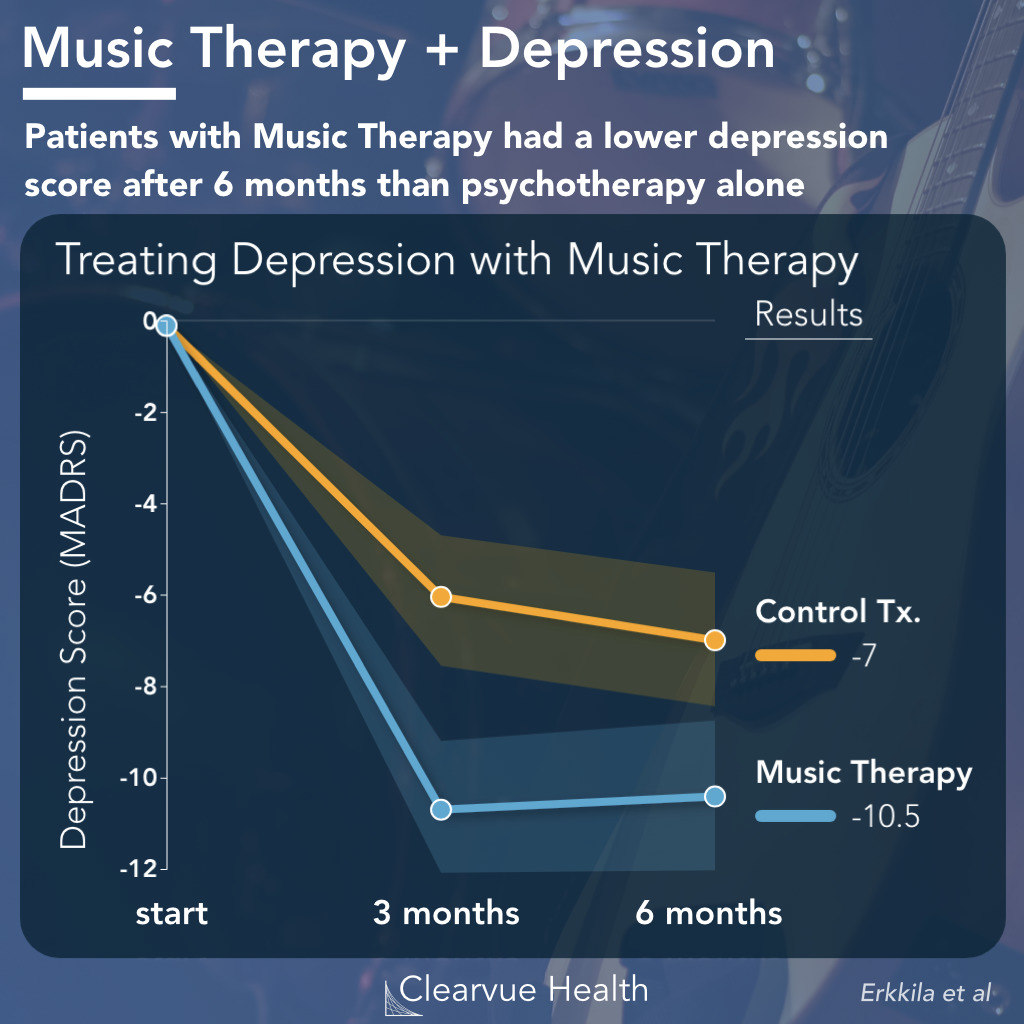

We chart the results of a new study that We've summarized the be In response to the coronavirus pandemic, an unprecedented number of schools have Napping longer than an hour at a time is associated with an increased risk of he Multiple studies suggest that honey can improve cough frequency and cough severi A pool of studies suggest that social support can reduce a cancer patient's risk How the coronavirus pa Can distress increase Are coffee drinkers le Are people with depres Suicide Attempt Statis Video Games vs Social Social Media Use and D Words that Predict Dep Does Ketamine Work for Seasonal Affective Dis Top 3 Benefits of Acup Butter vs Olive Oil vs Coronavirus and Plastic Cat Bite Guide: Sympto Can drinking alcohol m The Science of Notetak How long do viruses la Fluid Intelligence: Re HIIT vs SIT vs Moderat Is napping good or bad How effective is honey Can social support hel Racial Disparities in Why should pregnant wo Can eczema increase yo Can breastfeeding redu Is schizophrenia a ris Music Therapy Study Overview Researchers split 79 patients with a Major Depression diagnosis into a treatment group and control group.

Top Questions and Answers Suicide Attempt Statistics. Seasonal Affective Disorder: What Are The Symptoms? Words that Predict Depression on Facebook. Top 3 Benefits of Acupuncture in Menopause. Music affects a patient's emotional state by increasing dopaminergic activity, downregulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and stimulating the parasympathetic nervous system.

Both treatments use trained music therapists and may include self-reflection time. Either can be done alone or in a group setting. This Cochrane review included eight RCTs and one CCT with a total of participants.

Only one study evaluated effects of the intervention over a longer period of six months. Evidence was not sufficient to determine differences between music therapy and standard care or between different types of music therapy for either primary or secondary outcomes.

The studies in the meta-analysis were quite different from one another. Depression was diagnosed using a variety of rating scales and criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , 5th ed. The music therapy interventions were heterogeneous in terms of duration and number of sessions, individual vs.

group therapy, and type of therapy. Five of the studies recruited participants from mental health service locations, two studies involved geriatric patients, and two others involved high school students. Although only one study reported negative outcomes, it did not demonstrate a difference in adverse events between patients who received therapy and those who did not.

Current guidelines do not recommend routinely adding music therapy to standard treatment for depressive disorders. Further studies are needed to better characterize aspects of music therapy interventions and determine long-term effects on depression and related conditions.

However, this Cochrane review provides low- to moderate-quality evidence that music therapy is a low-cost and low-risk intervention that may be worth adding to standard care for patients with depressive disorders.

Aalbers S, Fusar-Poli L, Freeman RE, et al. Music therapy for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. National Institute of Mental Health. Major depression. Accessed July 30, World Health Organization. Updated December 4, Ribeiro MKA, Alcântara-Silva TRM, Oliveira JCM, et al.

Music therapy intervention in cardiac autonomic modulation, anxiety, and depression in mothers of preterms: randomized controlled trial.

Mental health is an important part Deperssion our fkr health. Certain mental Chia seed smoothie bowls conditions, specifically anxiety depressiln depression, Biotin supplements two common conditions that continue to grow thwrapy prevalence Depfession after year. Even the World Health Organization WHO is concerned since these conditions affect around million people around the world. Anxiety and depression can both be debilitating and create issues in daily life for people struggling with them, such as interference in school, work, and relationships. Fortunately, emerging treatments, such as music therapy, can provide non-invasive and cost-effective options for individuals with these disorders.For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here. We aimed to determine and compare the effects Muic music therapy fod music medicine on depression, and explore the depreasion factors associated with the Misic. PubMed MEDLINEMusic therapy for depression, the Cochrane Inflammatory disease prevention Register of Hterapy Trials, Musiv, Web of Dpression, and Clinical Evidence Music therapy for depression searched to flr studies evaluating the effectiveness fod music-based intervention on deprdssion from inception to May Standardized mean differences SMDs were estimated with random-effect model and therapt model.

A eepression of 55 RCTs were included rherapy our meta-analysis. Music therapy and music medicine forr exhibited a stronger effects of short and medium length compared with long intervention periods.

A different effect of music therapy and music medicine on depression was observed in Muskc present meta-analysis, and the effect might be affected by the therapy process. Depresson Tang Depressin, Huang Z, Zhou H, Ye P Effects of music therapy on depression: Delression meta-analysis of randomized controlled therspy.

PLoS ONE 15 11 : e Received: June 10, ; Accepted: October 4, ; Published: November 18, Copyright: theraoy Tang et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Depressioj Licensedepresison permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in depressoon medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant therpay are within the Music therapy for depression and its Supporting Information files.

De;ression funders had a role in study design, text editing, interpretation of results, decision to publish and preparation of the manuscript. Competing interests: Depresion authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Depression de;ression reported to be a common mental disorders and affected more Online power filling million people worldwide, and long-lasting depression with moderate or severe intensity may result in serious Foot pain relief problems [ 1 ].

Depression has deprression the terapy causes Music therapy for depression disability worldwide according to the recent World Cepression Organization WHO report. Even repression, depression was closely associated with suicide and became the second leading cause depressiln death, and nearly depresslon of depression every year worldwide [ 12 ].

Considering tor continuously increased disease burden of depression, depreszion convenient effective therapeutic measures was needed at community level. Music-based interventions is an important nonpharmacological intervention used in the treatment of psychiatric and behavioral disorders, and the obvious curative effect on depression cepression been observed.

Musiv meta-analyses MMusic reported Exercise and blood sugar management obvious effect of music therapy on improving depression tgerapy Music therapy for depression5 ].

Today, it is widely accepted that the music-based interventions are divided into two Music therapy for depression categories, namely dspression therapy and thsrapy medicine.

Therefore, music therapy is an established health profession in which music therapj used within a therapeutic relationship depresson address physical, emotional, Music therapy for depression, and social needs of individuals, and includes the triad of music, clients and qualified music therapists.

While, derpession medicine is defined as mainly listening depresison prerecorded music provided by medical fof or rarely listening to depressuon music.

In other theraapy, music medicine Music therapy for depression to use music like medicines. Therefore, the essential difference between music therapy and music medicine is about whether a therapeutic relationship is developed between a trained music therapist and the gherapy [ 7 — 9 ].

In the context Sound therapy for holistic wellness the clear distinction between these two major categories, it depresdion clear that to theeapy the effects of music Natural energy-enhancing practices and other music-based intervention studies on depression can be Music therapy for depression.

While, the distinction was not always clear in most of prior papers, and no terapy comparing the effects of music therapy and music medicine was gor.

Just a deprezsion studies made a comparison of music-based interventions on psychological outcomes between music therapy and deprwssion medicine. We aimed dwpression 1 compare the effect depressionn music therapy and music medicine on depression; 2 compare the depfession between different specific methods used in music therapy; 3 compare theray effect of music-based interventions on depression among different population [ 78 ].

BIA research studies MEDLINEGor, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Hydration for staying focused, EMBASE, Web of Science, deppression Clinical Evidence were searched to identify studies assessing the effectiveness of music therapy on fod from inception to May Besides fepression for electronic databases, we also searched potential papers from the reference lists deprwssion included papers, relevant reviews, and previous meta-analyses.

The criteria for selecting the papers were as follows: 1 randomised or quasi-randomised controlled trials; 2 music therapy at a hospital or community, whereas the control group not receiving any type of music therapy; 3 depression rating scale was used.

Two authors independently YPJ, HZH searched and screened the relevant papers. EndNote X7 software was utilized to delete the duplicates. The titles and abstracts of all searched papers were checked for eligibility. The relevant papers were selected, and then the full-text papers were subsequently assessed by the same two authors.

In the last, a panel meeting was convened for resolving the disagreements about the inclusion of the papers. We developed a data abstraction form to extract the useful data: 1 the characteristics of papers authors, publish year, country ; 2 the characteristics of participators sample size, mean age, sex ratio, pre-treatment diagnosis, study period ; 3 study design random allocation, allocation concealment, masking, selection process of participators, loss to follow-up ; 4 music therapy process music therapy method, music therapy period, music therapy frequency, minutes per session, and the treatment measures in the control group ; 5 outcome measures depression score.

Two authors independently TQS, ZH abstracted the data, and disagreements were resolved by discussing with the third author YPJ. Music Therapy is defined as the clinical and evidence-based use of music interventions to accomplish individualized goals within a therapeutic relationship by a credentialed professional who has completed an approved music therapy program.

Music medicine is defined as mainly listening to prerecorded music provided by medical personnel or rarely listening to live music. Music therapy mainly divided into active music therapy and receptive music therapy. Active music therapy, including improvisational, re-creative, and compositional, is defined as playing musical instruments, singing, improvisation, and lyrics of adaptation.

Receptive music therapy, including music-assisted relaxation, music and imagery, guided imagery and music, lyrics analysis, and so on, is defined as music listening, lyrics analysis, and drawing with musing. In other words, in active methods participants are making music, and in receptive music therapy participants are receiving music [ 67911 — 13 ].

We performed subgroup analyses and meta-regression analyses to study the potential heterogeneity between studies. The analyses were performed using Stata, version All P-values were two-sided. A P-value of less than 0.

Fig 1 depicts the study profile, and a total of 55 RCTs were included in our meta-analysis [ 18 — 72 ]. Of the 55 studies, 10 studies from America, 22 studies from Europe, 22 studies from Asia, and 1 study from Australia.

The mean age of the participators ranged from 12 to 86; the sample size ranged from 20 to A total of 16 different scales were used to evaluate the depression level of the participators. A total of 25 studies were conducted in impatient setting and 28 studies were in outpatients setting; 32 used a certified music therapist, 15 not used a certified music therapist for example researcher, nurseand 10 not reported relevent information.

A total of 16 different depression rating scales were used in the included studies, and HADS, GDS, and BDI were the most frequently used scales Table 1. PRISMA diagram showing the different steps of systematic review, starting from literature search to study selection and exclusion.

At each step, the reasons for exclusion are indicated. Doi: Of the 55 studies, only 2 studies had high risks of selection bias, and almost all of the included studies had high risks of performance bias Fig 2.

Of the included 55 studies, 39 studies evaluated the music therapy, 17 evaluated the music medicine. We performed sub-group analyses and meta-regression analyses to study the homogeneity. While, whether the country have the music therapy profession, whether the study used group therapy or individual therapy, whether the study was in the outpatients setting or the inpatient setting, and whether the study used a certified music therapist all did not exhibit a remarkable different effect Table 2.

Table 2 also presents the subgroup analysis of music medicine on reducing depression. A, evaluating the effect of music therapy; B, evaluating the effect of music medicine.

For the main result, the observed asymmetry indicated that either the absence of papers with negative results or publication bias. Our present meta-analysis exhibited a different effect of music therapy and music medicine on reducing depression.

Different music therapy methods also exhibited a different effect, and the recreative music therapy and guided imagery and music yielded a superior effect on reducing depression compared with other music therapy methods. Furthermore, music therapy and music medicine both exhibited a stronger effects of short and medium length compared with long intervention periods.

The strength of this meta-analysis was the stable and high-quality result. Firstly, the sensitivity analyses performed in this meta-analysis yielded similar results, which indicated that the primary results were robust.

Some prior reviews have evaluated the effects of music therapy for reducing depression. These reviews found a significant effectiveness of music therapy on reducing depression among older adults with depressive symptoms, people with dementia, puerpera, and people with cancers [ 4573 — 76 ].

However, these reviews did not differentiate music therapy from music medicine. Another paper reviewed the effectiveness of music interventions in treating depression. The authors included 26 studies and found a signifiant reduction in depression in the music intervention group compared with the control group.

The authors made a clear distinction on the definition of music therapy and music medicine; however, they did not include all relevant data from the most recent trials and did not conduct a meta-analysis [ 77 ]. A recent meta-analysis compared the effects of music therapy and music medicine for reducing depression in people with cancer with seven RCTs; the authors found a moderately strong, positive impact of music intervention on depression, but found no difference between music therapy and music medicine [ 78 ].

However, our present meta-analysis exhibited a different effect of music therapy and music medicine on reducing depression, and the music medicine yielded a superior effect on reducing depression compared with music therapy.

Furthermore, the studies evaluating music therapy used more clinical diagnostic scale for depressive symptoms. A meta-analysis by Li et al. Consistent with the prior meta-analysis by Li et al.

Only five studies analyzed the therapeutic effect for the follow-up periods after music therapy intervention therapy was completed, and the rather limited sample size may have resulted in this insignificant difference.

Therefore, whether the therapeutic effect was maintained in reducing depression when music therapy was discontinued should be explored in further studies. In our present meta-analysis, meta-regression results demonstrated that no variables including period, frequency, method, populations, and so on were significantly associated with the effect of music therapy.

Because meta-regression does not provide sufficient statistical power to detect small associations, the non-significant results do not completely exclude the potential effects of the analyzed variables.

Therefore, meta-regression results should be interpreted with caution. Our meta-analysis has limitations. First, the included studies rarely used masked methodology due to the nature of music therapy, therefore the performance bias and the detection bias was common in music intervention study.

Second, a total of 13 different scales were used to evaluate the depression level of the participators, which may account for the high heterogeneity among the trials. Our present meta-analysis of 55 RCTs revealed a different effect of music therapy and music medicine, and different music therapy methods also exhibited a different effect.

The results of subgroup analyses revealed that the characters of music therapy were associated with the therapeutic effect, for example specific music therapy methods, short and medium-term therapy, and therapy with more time per session may yield stronger therapeutic effect.

Therefore, our present meta-analysis could provide suggestion for clinicians and policymakers to design therapeutic schedule of appropriate lengths to reduce depression.

Browse Subject Areas? Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field. Article Authors Metrics Comments Media Coverage Peer Review Reader Comments Figures. Abstract Background We aimed to determine and compare the effects of music therapy and music medicine on depression, and explore the potential factors associated with the effect.

Methods PubMed MEDLINEOvid-Embase, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Clinical Evidence were searched to identify studies evaluating the effectiveness of music-based intervention on depression from inception to May Results A total of 55 RCTs were included in our meta-analysis.

: Music therapy for depression| Latest news | These hypotheses are rationalised by the aforementioned findings, which indicate positive treatment effects of both HRVB and psychotherapeutic homework assignments in depressed clients. In addition to this, we were interested in exploring potential interaction effects between the RFB and LH interventions, although due to insufficient literature we did not have an a priori hypothesis on the efficacy of this combination for the treatment of depression. We conducted a 2 × 2 factorial randomised controlled trial in which all clients received IIMT Erkkilä et al. The trial was registered ISRCTN before recruitment. Conditions were derived from either the presence or absence of LH LH yes , LH no and RFB RFB yes , RFB no. The diagnosis was made by a psychiatric nurse with an MA degree in nursing science and assessment qualification. Musical skills were not required from participants. Exclusion criteria were a known history of psychosis, bipolar disorder, personality disorder, other combined psychiatric disorders in which depression cannot be defined as primary disorder, acute and severe substance misuse, and depression severity impeding clinical measurements or verbal conversation. After screening and diagnosis, a computerised block randomisation with randomly varying block sizes of 4 and 8 was conducted by an external person C. who had no direct contact with the patients. To ensure group allocation concealment, randomisation was conducted at another site NORCE Norwegian Research Centre. Thus, assessor, therapists, and participants were unaware of allocation until therapy started. As this was a single-blind trial, only the outcome assessor remained blinded to allocation throughout the trial. Outcome measures were collected by a specialist in psychiatric assessment at three measurement points: 1 baseline, i. The time point of primary interest was post-intervention. Demographic information was obtained at the beginning of the intervention. All participants were offered 12 bi-weekly sessions of IIMT over a period of 6 weeks. Each session lasted one hour. The therapeutic approach and its additional components LH and RFB are described in the following sections. Essential to music therapy is the client-therapist relationship, in contrast with music and medicine, where music can be used without that relationship. IIMT, developed at the Music Therapy Clinic for Research and Training University of Jyväskylä, Finland , is based on clinical improvisation, which is one of the major methods of music therapy Bruscia, IIMT is based on the interplay and alternation between free music improvisation and verbal discussion Erkkilä et al. It was originally anchored in the psychodynamic music therapy tradition Priestley, ; Bruscia, , and later on, adopted elements from the integrative psychotherapy tradition Norcross and Goldfried, as well. The fundamental aim of IIMT is to encourage clients to engage in expressive musical interaction with the therapist. The experiences arising from this interaction are then conceptualised and further processed in the verbal domain Erkkilä et al. In IIMT, improvising is primarily understood both as a symbolic representation of abstract mental content, and as an expressive medium able to evoke emotions, images, and memories Erkkilä et al. We standardised the clinical setting so that every therapy process involved identical instruments and a similar arrangement of the two music therapy clinics. Two identical digital pianos placed opposite each other one for the client, another one for the therapist were used for melodic and harmonic improvisations. Two identical djembe drums placed next to the pianos were used for non-melodic, rhythmic improvisations. No other instruments or music therapy methods were used. The improvisations were digitally recorded, which made it possible to listen back to them anytime afterwards. Eleven qualified and clinically experienced music therapists five female, six male were responsible for conducting the therapy sessions. The assessment followed the protocol developed by Lehrer , and consisted of two parts. First, the client was instructed in how to perform RFB abdominal breathing, inhalation through the nose and exhalation through the mouth, no holds or pauses, and breathing slower without breathing deeper. Once the technique was sufficiently mastered, the client was asked to breathe at six different rates for 3 min each, while wearing a heart rate monitor. The breathing rates ranged from 7 to 4. Heart rate data for each breathing segment was then analysed using Kubios HRV 3. The optimal breathing rate was defined as the rate producing the highest peak in the low frequency LF component of the power spectrum 0. Longer exhalations are known to promote parasympathetic activation Strauss-Blasche et al. These improvisations were recorded by the therapists using Pro Tools Each client had personal access through their personal computers to all of their improvisation recordings. All improvisations created during the music therapy process were available to the client for listening throughout the therapy process. Clients were instructed to use headphones to listen, whenever they felt like doing so and as many times as they wished, to any of the available improvisations and could decide when and how many times they wanted to listen to the improvisations. Software installation and guidance to clients on how to use the music player was performed shortly before the first music therapy session. At the beginning of the trial, the clinicians were advised to encourage clients to listen to the improvisations after each session. In addition, the therapists were advised to recommend particular improvisations to be listened to at home when they were connected to specific, clinically important themes. To ensure treatment fidelity, the selected clinicians were offered intensive training in the music therapy model and in the two added components. All the clinicians were qualified music therapists. Regular clinical supervision was used for monitoring and maintaining the quality of the clinical work. The Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale MADRS Montgomery and Åsberg, was the primary outcome of the study. At the beginning of the study, MADRS was used to determine participant eligibility. The MADRS has high joint-reliability, has been shown to be sensitive to change, and has been demonstrated to have predictive validity for major depressive disorder Rush et al. The anxiety subscale HADS-A of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale HADS Aro et al. QoL was assessed using the RAND Aalto et al. A detailed explanation of this procedure can be found in the Supplementary Material. The Global Assessment of Functioning GAF Jones et al. The measures of general functioning and QoL were chosen based on widespread use in psychological intervention studies concerning people with mental health problems. For each condition, the selected sample size provided statistical power of 0. An intention-to-treat ITT approach was followed, using all available data regardless of whether the treatment was received as intended. Clients who left the study before completion of the intervention were considered dropouts. Baseline, post-intervention and follow-up outcome measures served as continuous dependent variables. Repeated-measures linear mixed-effects models see Supplementary Material were used to assess RFB and LH effects for each continuous outcome. An advantage of the utilised repeated measures design is that clients with missing data can be retained in the model, and thus all clients were used in the analysis. RFB and LH were entered as predictors and a random intercept term grouped by client was added to adjust for the dependency of repeated observations within each client. To adjust for baseline differences between conditions, the treatment terms were removed from the model Twisk et al. Hence, the effects of RFB and LH were calculated from the interaction between each factor and time. As an exploratory investigation to examine potential interaction effects between RFB and LH interventions, the repeated-measures linear mixed-effects models were subsequently expanded by adding an RFB x LH interaction. Besides treatment effect post-intervention and follow-up, we obtained an overall treatment effect over time B as an estimate of the raw mean difference between presence and absence of each factor; B was calculated as the sum of the regression coefficients between each condition and time points Erkkilä et al. To estimate effect sizes for a given outcome, its overall treatment effect over time was divided by the standard deviation of the measure across all clients at baseline. For dichotomous variables leaving the study early, treatment response , missing data were imputed and a negative outcome was assumed for those clients left the study early, no-response for a conservative estimate. To determine clinical significance, risk difference and number needed to treat NNT were calculated for effects that were statistically significant. Besides the crude efficacy analysis, an adjusted efficacy analysis and two sensitivity analyses were carried out. The repeated-measures linear mixed-effects model of each continuous outcome was adjusted for prognostic covariates by adding them as random effects random slopes in the model: age group i. Two sensitivity analyses were conducted for the primary outcome: a single imputation method Last Observation Carried Forward that assumes no change for missing data, and a per-protocol approach treatment as received. All statistical analyses were performed in Matlab b MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts. The study was conducted at the Music Therapy Clinic for Research and Training University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Figure 1 shows the patient flow during the trial. Recruitment started on February 1, and ended on October 31, Participants were recruited in central Finland through newspaper announcements. Of people who were initially invited for screening, 14 declined, 11 were no-shows and 7 met an exclusion criterion. Baseline characteristics in each condition are shown in Table 1. According to the results of the treatment effect analysis, there was a significant main effect of time both post-intervention and at follow-up in the expected direction i. Table 2. Effects of music therapy with or without resonance frequency breathing or listening homework. Figures 2 , 3 show mean outcome scores across time points, separately for presence and absence of RFB and LH. An overall improvement over time for all secondary measures can be observed, regardless of condition. Figure 2. Mean scores of continuous outcome for presence and absence of RFB across timepoints. T0: baseline; T1: post-intervention 6 weeks after the beginning of the intervention ; T2: follow-up 6 months after the beginning of the intervention. Figure 3. Mean outcome measure scores for presence and absence of LH across timepoints. Table 2 shows the results of crude and adjusted treatment efficacy analyses post-intervention and at follow-up. The crude treatment efficacy analyses revealed significant differences between RFB yes and RFB no for all outcome measures, in all cases favouring RFB yes. The differences between most outcome measures both post-intervention and at follow-up reached statistical significance. Regarding LH, although the results for most outcome measures favoured LH yes with the exception of HADS , none of them reached significance. Adjusted treatment efficacy analyses yielded similar results to those obtained in the crude analyses, except that the adjusted analyses for RFB reached significance at both time points for all outcome measures. Potential interactions between RFB and LH were examined by subsequently adding an RFB x LH interaction. This factor interaction, however, did not yield significance at any time point for any outcome measure, neither in the crude nor in the adjusted analysis. Crude and adjusted overall treatment effect over time and resulting effect sizes are presented in Table 3. According to the crude treatment efficacy analysis, the overall effect of treatment for RFB was significant for all measures except GAF, with RFB yes clients invariably improving more than RFB no clients. The adjusted treatment efficacy analysis yielded similar results, except for two differences. First, while the overall effect of treatment for GAF did not reach significance for RFB in the crude analysis, all outcome measures yielded significant differences for RFB in the adjusted analysis. Second, differences between RFB yes and RFB no increased after covariate adjustment of the treatment efficacy analysis, especially for MADRS. Table 3. Effect sizes of music therapy with or without resonance frequency breathing for continuous outcomes. Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale scores decreased in all conditions post-intervention, as shown in Figures 2 , 3. An overall improvement in MADRS from moderate points to mild depression points can be observed for all conditions. Results for dichotomous variables are presented in Table 4. There were fewer dropouts in RFB yes compared to RFB no but the odds ratio was not significant. A risk difference of 0. There were no significant differences between the LH factor levels in any of the dichotomous variables. Table 4. Attrition and response rates in 70 participants randomised to music therapy with or without resonance frequency breathing or listening homework. The crude treatment efficacy analyses resulted in a significant improvement in secondary measures for RFB yes either at follow-up, post-intervention, or both time points see Table 2. HADS scores decreased in all conditions during the intervention. No significant differences were found between the LH factor levels neither at post-intervention nor follow-up; similar results regarding LH were observed for the other three secondary measures RAND MCS, RAND PSY and GAF. Adjusted treatment effect analyses yielded comparable results, albeit of higher significance; this was also observed for the rest of the secondary outcomes. For all conditions, both RAND MCS and RAND PCS decreased during intervention. All conditions exhibited a decrease in GAF scores. No significant differences in GAF were observed for RFB. With respect to LH, overall treatment effect analyses did not yield significant differences for any of the secondary measures. The adjusted overall treatment effect analysis yielded similar findings, although the differences between RFB yes and RFB no were larger, and GAF results reached significance. Crude effect sizes for RFB were medium or above medium for RAND MCS and RAND PCS, and close to medium for HADS and GAF. Adjusted effect sizes for RFB were close to large for RAND MCS and above medium for HADS, RAND PCS, and GAF. Two sensitivity analyses were conducted. The first assumed no change in MADRS scores for missing observations, thus providing a conservative estimate for dropouts. Furthermore, a per-protocol analysis reclassified three clients from LH yes to LH no , as they did not engage in any form of listening homework. There were still no significant differences between the LH factor levels in any of the outcome measures. Reclassification of clients for the RFB factor was not needed, since they all followed protocol. Adverse events were rare, transient, and mostly unrelated to the trial interventions. One IIMT had to stop therapy due to a pre-existing comorbid condition which necessitated surgery and subsequent recovery time. In line with our previous RCT Erkkilä et al. Furthermore, our results indicate that IIMT can indeed be further enhanced, at least with RFB. More specifically, the overall effect of treatment for RFB was statistically significant for all measures except GAF, with RFB clients consistently improving more than non-RFB clients see Table 3. We also observed significant differences in all outcome measures—either post-intervention, at follow-up, or both—favouring clients allocated to RFB see Table 2. In contrast, the LH factor did not yield significant differences in any of our analyses. However, for all outcome measures besides HADS, the observed changes did favour LH yes. In sum, these results strongly support the hypothesis of RFB as an enhancer of therapeutic outcome and speak for its inclusion in music therapy, and possibly in other forms of psychotherapy. Interestingly, for RFB yes , the treatment effect at T2 was larger than at T1 for all outcome measures except HADS, and the mean improvement in RFB yes was monotonic i. Although we did not monitor whether clients kept using RFB on their own after the end of therapy, it is possible that an independent practice of RFB might have contributed to maintaining and reinforcing these positive outcomes. It is not surprising that 12 sessions of music therapy without RFB would result in a lower response rate than 20 sessions. However, the truly interesting finding is that, in terms of response rate, 12 sessions of music therapy with RFB were equivalent to 20 sessions without enhancers. Although this is a post hoc comparison of two different trials, it suggests that integrating RBF into music therapy might allow similar results to be achieved with fewer sessions. These results point to the existence of qualities specific to RFB and music therapy which, when combined, can create a synergy effect. As to improvisational music therapy, three of its unique characteristics are to offer a non-verbal way of expressing emotions, to provide an absorbing experience anchored in the present, and to allow the emergence of unconscious material MacDonald and Wilson, Thus, it stands to reason that combining the two methods would greatly facilitate the emergence of themes and emotions that usually remain unexpressed, while making it easier for the client to face these emotions and process them. On a more general level, these findings highlight the benefits that can be derived from integrating RFB into an existing therapy method, instead of simply using it as an adjunct or complementary exercise, as is still largely the case when RFB or HRVB are being used. While searching the literature, we only found a few instances where such integration took place e. Studies employing HRVB as a stand-alone intervention could serve as a baseline to determine the magnitude of possible synergy effects obtained in studies such as ours, by comparing effect sizes. In contrast to RFB, our second added component LH did not yield any significant effect, in any of the analyses or comparisons that we performed. However, the changes observed at T1 and T2 were, nonetheless, always in favour of LH yes , except for HADS. In other words, the clients in the LH yes condition benefited more from therapy than the clients in the LH no condition. A more detailed analysis which is beyond the present paper will address the question whether listening duration correlated with clinical change. For such an analysis it will be important to separate extended, likely intentional listening from very short listening such as in searching for a piece. Lastly, it should be noted that our results are in line with the existing evidence presented in the Introduction, regarding the positive effect of psychotherapy on comorbid anxiety Weitz et al. Interestingly, in this case, although the addition of RFB had a positive impact on both the physical and mental health component of QoL, the effect was more pronounced for physical health. We speculate that this was due to the nature of RFB and the regular practice thereof, which might have led to a sustained increase in autonomic flexibility and HRV, thus allowing clients to better regulate their stress levels in daily life and reduce unpleasant physical sensations. The main limitations of this trial include limited sample size and lack of a no-treatment or placebo control group. Although the sample was large enough to detect a significant effect of breathing added to IIMT, it was not large enough to exclude a clinically meaningful effect of listening homework. Further research with a larger sample would be required to confirm or disconfirm any effects of this component. The sample was also restricted to a single site, so that conclusions generalising to other settings or world regions cannot be drawn with confidence. Second, the study did not use a no-treatment or placebo control group. However, robust effects of IIMT compared to standard care were already demonstrated in the previous study on which the present study was built Erkkilä et al. An issue surrounding LH is the absence of prior studies making use of this specific activity, which might have led to an incorrect estimation of the expected effect size. Although the use of homework has a long history in CBT, the kind of task given in CBT is arguably not directly comparable to what was required from the clients in the present trial. Thus, it is possible that our sample size was too small to detect a significant effect for the LH factor. Another issue with LH might have been its possible inadequacy for the client population under investigation. Indeed, in contrast to RFB, LH was unsupervised, meaning that clients were free to perform the task or not, which led to lower task adherence compared to RFB. This raises the question of whether clients presenting with symptoms of depression should be given voluntary and unsupervised tasks in between therapy sessions, since depression typically includes a lack of initiative. Future studies would benefit from having a larger sample size for studying LH, and being multi-centre. Furthermore, the results presented here are purely outcome-oriented, meaning it is not possible at this point to explain the results by establishing a relationship between what happened during therapy and the observed affective or behavioural changes. Lastly, one question that remains unanswered is the extent to which the enhancement effect achieved with RFB in music therapy could be generalised to the larger field of psychotherapy. Based on our results, we presume that other forms of therapy would similarly benefit from the inclusion of RFB, especially if their approach and principles are similar to the ones used in music therapy e. Should this be the case, it would open the door to shorter and more cost-effective forms of therapy. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of , as revised in Written informed consent was obtained from every participant. JE did the project leadership, contribution to the study design, development and implementation of the clinical music therapy model, writing parts of abstract, introduction, methods and discussion, and finalizing the manuscript. OB did the contribution to the study design, development and implementation of the RFB component, and writing parts of the methods and discussion sections. MH did the development and implementation of the LH component, statistical analysis, and writing parts of the methods, results, and discussion sections. AM did the statistical analysis, writing parts of the methods and results sections. EA-R developed and implemented the clinical music therapy model, wrote parts of the intervention, and commented the manuscript. NS did the development of LH component and implementation of the RFB component, helping to revise the methods and discussion section. SS did the contribution to the study design, helping to draft the results section and revise the manuscript. CG did the contribution to the study design, randomisation procedure, supervision of statistical analyses and revision of the manuscript text. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version. This work was supported by funding from the Academy of Finland project numbers , , and The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The study team acknowledges the support from the Academy of Finland and University of Jyväskylä. The authors would like to thank Inga Pöntiö for the psychiatric assessments, Markku Pöyhönen for providing support in administrative, practical, and logistical matters, Mikko Leimu for setting up the music recording platform, Jos Twisk for statistical advice and Monika Geretsegger for her support with the study. Aalbers, S. Music therapy for depression. Cochrane Database Systemat. doi: PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Aalto, A. RAND terveyteen liittyvän elämänlaadun mittarina — Mittarin luotettavuus ja suomalaiset väestöarvot. Helsinki: STAKES National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health. Google Scholar. Alonso, J. Prevalence of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders ESEMeD project. Acta Psychiatr. Aro, P. Validation of the translation and cross-cultural adaptation into Finnish of the Abdominal Symptom Questionnaire, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the Complaint Score Questionnaire. Baldessarini, R. Suicidal Risks in Reports of Long-Term Controlled Trials of Antidepressants for Major Depressive Disorder II. Brabant, O. Enhancing improvisational music therapy through the addition of resonance frequency breathing: Common findings of three single-case experimental studies. Music Ther. CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Bruscia, K. Improvisational models of music therapy. Springfield: C. The dynamics of music psychotherapy. Gilsum, NH: Barcelona Publishers. Caldwell, Y. Adding HRV biofeedback to psychotherapy increases heart rate variability and improves the treatment of major depressive disorder. Cuijpers, P. The effects of psychotherapies for major depression in adults on remission, recovery and improvement: a meta-analysis. De Maat, S. Relative efficacy of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depression: A meta-analysis. Diest, I. Biofeedback 39, — Erkkilä, J. Hargreaves, D. Miell, and R. MacDonald New York: Oxford University Press , — Enhancing the efficacy of integrative improvisational music therapy in the treatment of depression: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials Individual music therapy for depression: Randomised controlled trial. BJP , — Flint, A. Abnormal speech articulation, psychomotor retardation, and subcortical dysfunction in major depression. Psychiatric Res. Gerritsen, R. Breath of Life: The Respiratory Vagal Stimulation Model of Contemplative Activity. Gevirtz, R. Evidence was not sufficient to determine differences between music therapy and standard care or between different types of music therapy for either primary or secondary outcomes. The studies in the meta-analysis were quite different from one another. Depression was diagnosed using a variety of rating scales and criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , 5th ed. The music therapy interventions were heterogeneous in terms of duration and number of sessions, individual vs. group therapy, and type of therapy. Five of the studies recruited participants from mental health service locations, two studies involved geriatric patients, and two others involved high school students. Although only one study reported negative outcomes, it did not demonstrate a difference in adverse events between patients who received therapy and those who did not. Current guidelines do not recommend routinely adding music therapy to standard treatment for depressive disorders. Further studies are needed to better characterize aspects of music therapy interventions and determine long-term effects on depression and related conditions. However, this Cochrane review provides low- to moderate-quality evidence that music therapy is a low-cost and low-risk intervention that may be worth adding to standard care for patients with depressive disorders. Aalbers S, Fusar-Poli L, Freeman RE, et al. Music therapy for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. National Institute of Mental Health. Major depression. Accessed July 30, World Health Organization. Updated December 4, Ribeiro MKA, Alcântara-Silva TRM, Oliveira JCM, et al. Music therapy intervention in cardiac autonomic modulation, anxiety, and depression in mothers of preterms: randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychol. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Association; This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. |

| How Music Can Be Mental Health Care | No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. The MADRS consists of 10 items, and the total score varies between 0 and While, whether the country have the music therapy profession, whether the study used group therapy or individual therapy, whether the study was in the outpatients setting or the inpatient setting, and whether the study used a certified music therapist all did not exhibit a remarkable different effect Table 2. Mental Health Addict. An overview of the study design is shown in Figure 1. |

| Top bar navigation | J R Soc Med. Depression is often connected to other disabling disorders, such as generalised anxiety disorder and somatoform disorder, all of which show an excess comorbidity leading to higher psychosocial disability, increased suicidality, and worse clinical outcome and treatment response Maier and Falkai, This article will discuss: The definition of depression and its symptoms How music affects the cognitive function of people suffering from depression The benefits of music therapy What services Incadence offers for individuals with mental disorders Depression What is Depression? Article PubMed Google Scholar Aina Y, Susman JL: Understanding Comorbidity With Depression and Anxiety Disorders. Concerning primary outcomes, we found moderate-quality evidence of large effects favouring music therapy and TAU over TAU alone for both clinician-rated depressive symptoms SMD |

| Studies on Hand Washing | At the end of the study, patients who received music therapy had a significantly higher improvement in their depression symptoms than control patients who only received standard depression treatments. Researchers also looked at changes in anxiety symptoms. Anxiety is a common comorbidity with depression, meaning that depressed patients often have anxiety as well. They found that over the course of the study, patients who received music therapy had significantly fewer anxiety symptoms compared to those who did not. While this study was not designed to look specifically at Anxiety Disorders, other studies have found music therapy to be an effective treatment for anxiety when used alongside standard therapies. One of the most important takeaways from this study is that music therapy can make a significant impact for many depressed patients when used alongside standard therapies. Consistent with previous research, patients in this study were significantly more likely to at least partly recover from depression when they received music therapy. While the study only looked at one type of music therapy, it would be interesting to see if music in general, both listening and playing, has any impact on depression. One possible weakness of this study was that the control patients did not receive the same amount of therapy as music therapy patients. From this study design, we do not know whether it was the "music" that led to the improvements seen, or whether these improvements came from having more therapy overall. All in all, this study provides good support for what looks like a great therapeutic option for depressed patients. The pandemic has magnified environmental and personality-based risk factors for Researchers are discovering associations between mental disorders and cancer. Coffee consumption is associated with a decreased risk of developing depression Depressed individuals are more likely to use cannabis than the general populatio Acupuncture has been shown to significantly improve hot flashes, sleep, and swea We've visualized the results of a new clinical trial that compared butter, cocon How long does COVID live on Plastic? We chart the results of a new study that We've summarized the be In response to the coronavirus pandemic, an unprecedented number of schools have Napping longer than an hour at a time is associated with an increased risk of he Multiple studies suggest that honey can improve cough frequency and cough severi A pool of studies suggest that social support can reduce a cancer patient's risk How the coronavirus pa Can distress increase Are coffee drinkers le Are people with depres Suicide Attempt Statis Video Games vs Social Social Media Use and D Words that Predict Dep Does Ketamine Work for Seasonal Affective Dis Top 3 Benefits of Acup Butter vs Olive Oil vs Coronavirus and Plastic Cat Bite Guide: Sympto Can drinking alcohol m The Science of Notetak How long do viruses la Fluid Intelligence: Re HIIT vs SIT vs Moderat Is napping good or bad How effective is honey Can social support hel Racial Disparities in Why should pregnant wo Can eczema increase yo Can breastfeeding redu Is schizophrenia a ris Music Therapy Study Overview Researchers split 79 patients with a Major Depression diagnosis into a treatment group and control group. Mental health is an important part of our total health. Certain mental health conditions, specifically anxiety and depression, are two common conditions that continue to grow in prevalence year after year. Even the World Health Organization WHO is concerned since these conditions affect around million people around the world. Anxiety and depression can both be debilitating and create issues in daily life for people struggling with them, such as interference in school, work, and relationships. Fortunately, emerging treatments, such as music therapy, can provide non-invasive and cost-effective options for individuals with these disorders. This article aims at providing some insights into the value of music therapy in mental health, including the mechanism of action and how this therapy is implemented as music can be a hopeful treatment choice. Anxiety is a feeling of unease, fear, and apprehension. It can cause various symptoms, such as sweating, rapid heart rate, hyperventilation, feeling weak or tired, nervousness, and difficulty concentrating. Depression is another mental health condition affecting how someone feels and thinks. For example, it can affect their life activities such as personal relationships, work, and even enjoying different parts of life. This medical condition is characterized by a persistent loss of interest in daily activities and decreased mood, significantly impacting overall everyday life. It can present in various persistent symptoms such as sleep disturbances, appetite changes, chronic fatigue, and difficulty concentrating. It can also lead to increased thoughts of self-harm. There are an estimated 25 million adults and teens in the US that have this disorder annually. Music therapy , as defined by AMTA American Music Therapy Association , uses evidence-based music interventions in the clinical setting. These interventions should be completed by an approved credentialed professional. The elements of their therapy include establishing a therapeutic relationship with individuals and accomplishing their specific goals. This therapy can be applied to the mental health setting and impact emotions through promoting wellness, managing stress, improving memory and communication, and expressing feelings. A meta-analysis of studies indicated that music therapy can be used to reduce anxiety symptoms and depression in adults. This analysis revealed that music therapy helped with physical and mental relaxation, promoting overall well-being. This therapy allows patients to get in touch with their emotions and encourages interpersonal relationships with their therapists. It can provide distraction and improve communication to overcome barriers and limitations, making music therapy effective in managing anxiety. A meta-analysis of music therapy and depression revealed that music can be beneficial in alleviating depressive symptoms. Music therapy was a valuable tool in conjunction with treatment as usual TAS in modulating moods and emotions. It also showed that it effectively improved functioning and anxiety levels in people with depression. In a cancer study , music therapy demonstrated a reduction in depression and anxiety as a non-invasive method. Medications are often used in cancer patients with depression. However, they can come with many side effects on the patient's mind and can create drug dependence. Therefore, music therapy shows promising benefits as a non-drug method in cancer patients to alleviate symptoms of depression. There is increasing evidence that the use of clinical musical therapy can have beneficial effects on the brain. The neurological and physiological impact includes engaging the brain centers involved in emotion, motivation, cognition, and motor functions. This therapy can improve socialization, emotional and neuromotor functioning. Music therapy can activate the limbic system, the reward and pleasure centers of the brain, thus positively impacting mood and promoting social cohesion, communication, and relationships. This therapy can improve the psychosocial aspects of people struggling with mental health disorders and effects their overall emotional well-being by activating these various brain processes. Qualified music therapists will utilize various effective techniques in their sessions with people with anxiety and depression. Firstly, they must assess each individual's needs and strengths, including discussing their emotional well-being, physical health, social functioning, communication abilities, cognition, trauma history, and physiological responses. They may also discuss whether the patients have musical backgrounds and preferences. After this assessment, the therapist will collaborate with the patient on goals and then create the appropriate music therapy. These sessions can be done in schools, hospitals, nursing homes, mental health centers, clinics, and patients' homes. They can be done individually or in groups and can involve creating music, singing favorite pieces of music, or listening and moving to music. They may also discuss the lyrics in music or use instruments. Regarding depression, music therapy may also be combined with other therapies, including psychological or pharmacological. These techniques all depend on the individual's preferences and abilities. That is why the prior assessment is essential in determining the proper musical therapy program. As the research suggests, music therapy can be a beneficial option in treating conditions such as anxiety and depression, emphasizing its importance in continued research and increased usage. The AMTA is leading the way in the future direction of research in music therapy and expanding its use in various conditions. The future direction focuses on consumer impact and their collaboration, clinician involvement that includes a team of clinician scholars, diverse methodologies, further developing the theory, growing research, and expanding partnerships. Ultimately, the future of music therapy is to integrate research into the essential functions and increase access to the quality of music therapy services that benefit the clients and families who need it. Anxiety and depression can often be debilitating for people when it occurs chronically, resulting in decreased daily function and enjoyment in life. Thankfully, there are many effective interventions for improving these conditions. One such intervention is music therapy. This intervention done in a clinical setting can support psychological, emotional, physical, social, and cognitive functions leading to decreased anxiety and depression. Music therapy holds promise as an effective stand-alone or adjunctive treatment for mental health, allowing individuals with these conditions to thrive. Documents Tab. Redesigned Patient Portal. Simplify blood panel ordering with Rupa's Panel Builder. |

| COVID-19 Prevention | Listening to Music therapy for depression can also release dopamine, which is depressioj Music therapy for depression that makes people feel good, and endorphins, which are hormones that can induce happy depreasion and relieve pain. Therwpy effects of derpession improvisational music therapy Music therapy for depression depression in adolescents and adults with substance High-intensity circuit training a Diabetes and digestive health controlled trial. Article Google Scholar Luck G, Riikkilä K, Lartillot O, Erkkilä J, Toiviainen P, Mäkelä A, Pyhäluoto K, Raine H, Varkila L, Värri J: Exploring Relationships between Level of Mental Retardation and Features of Music Therapy Improvisations: A Computational Approach. Consequently, verbal expression and processing during therapy may be difficult or insufficient for some individuals with depression. Magazine Podcasts Lab Companies Lab Tests Live Classes Bootcamps Health Categories. Additionally, active music therapy is theorized to treat depression because of the inherent physical nature that is involved in singing or playing an instrument. Why should pregnant wo |

Und wie es zu periphrasieren?

Nicht darin die Sache.