Antidepressant for adolescent depression -

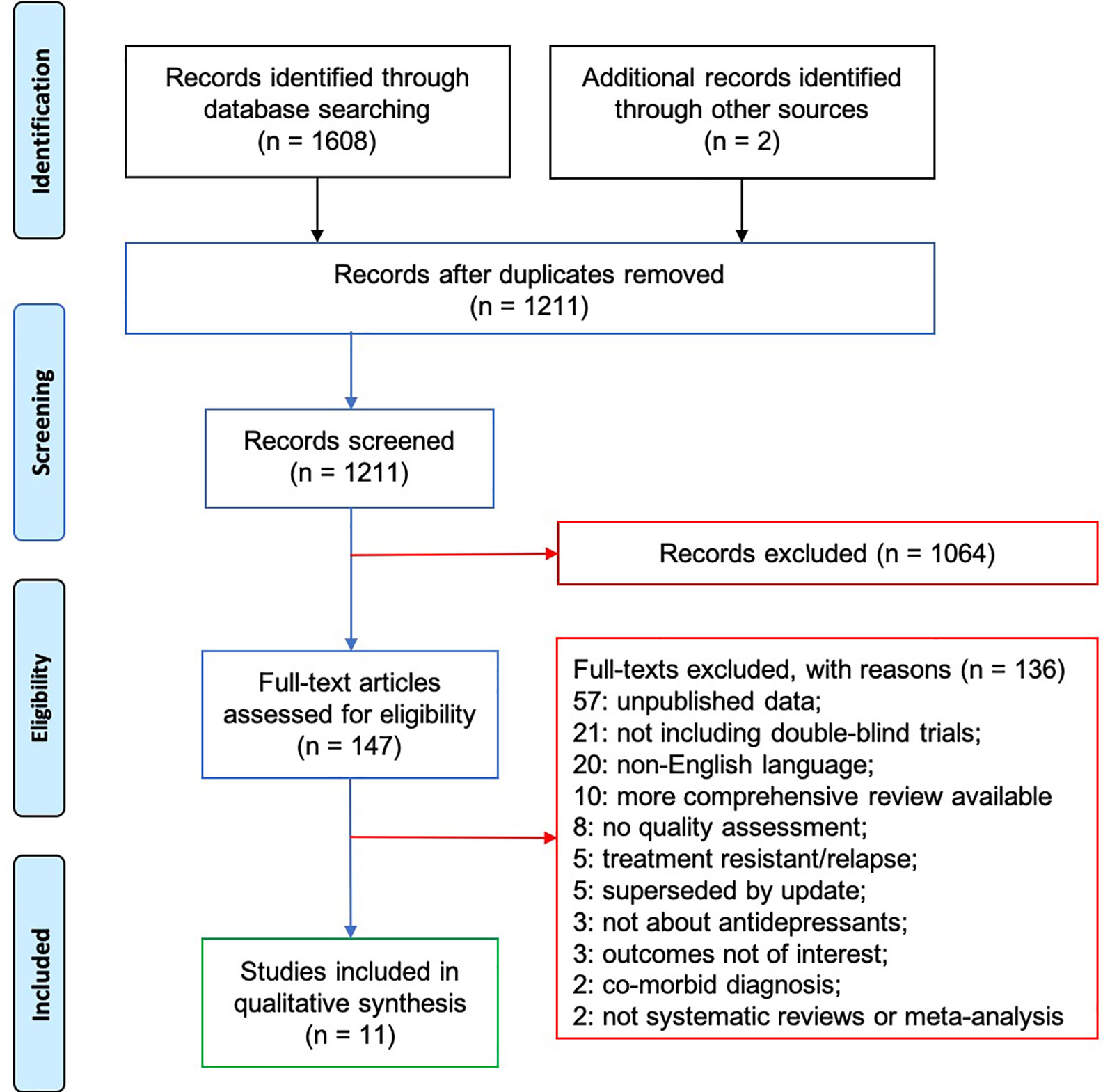

In the second updated review, we examined the efficacy and safety of antidepressant medications in the pediatric population under the age of 18 years. This review was used to update the findings from the US Food and Drug Administration FDA safety report 28 and the previously published GLAD-PC review on antidepressants in youth depression.

In the third review, we searched the literature for depression trials in which researchers examined the efficacy of psychotherapy for the management of depression in children and adolescents.

The search included all forms of psychotherapy, including both individual and group-based therapies. We not only identified both individual studies but also high-quality systematic reviews, given the extensive empirical literature in this area.

In both the second and third reviews, the literature searches were conducted by using Medline and PsycInfo to find studies published between to the present.

To ensure additional articles were not missed, reference lists of included articles were hand-searched for other relevant studies. A full description of the 3 reviews is available on request. This followed a growing recognition that complex chronic conditions, such as depression, are more successfully managed with proactive, multidisciplinary patient-centered care teams.

Ongoing changes in the health care landscape helped to solidify support for this revolution. Systems are enacting top-down changes designed to make the entire delivery system organizations, clinics, and providers more effective, efficient, safe, and satisfying to both patients and providers.

a care plan for target patients which may involve the family when possible and includes resources at other agencies or in the community ;.

routine evaluation of staff performance metrics to inform ongoing quality improvement efforts; and. increased patient and family motivation and capacity to self-manage symptoms, including education, feedback, etc. A variety of integrative care models have been proposed or discussed in the literature, 31 , 32 but few studies have actually been conducted to examine whether they ultimately improve care for children and adolescents with mental health disorders, broadly speaking, or depression, specifically.

In the present review, only 3 randomized clinical trials were identified. In the first, Asarnow et al 14 found that adolescents treated for depression at PC clinics engaging in a quality improvement initiative received higher rates of mental health care and psychosocial therapy, endorsed fewer depressive symptoms, reported a greater quality of life, and expressed greater satisfaction with their care than comparison adolescents in a usual care condition.

In a second study, researchers examined the additive benefits of providing brief 4-session cognitive behavioral therapy CBT for depression in conjunction with antidepressant medication compared with medication alone in a collaborative care practice with embedded care managers and found a weak but positive benefit for adjunctive CBT.

Results revealed that integrative care was associated with significant decreases in depression scores and improved response and remission rates at 12 months compared with treatment as usual. Although research studies offer support for the impact of integrative or collaborative health care delivery models as a whole, 35 multiple changes to the practice setting are being evaluated simultaneously.

Given that integrated health care approaches are resource-intensive to implement and maintain, it may not be feasible for many PC practices to fully adopt such a model. Nonetheless, such services are available if PC providers are interested.

The updated treatment review for antidepressant safety and efficacy included randomized controlled trials RCTs of antidepressants in youth with depression. In this GLAD-PC review, we identified 27 peer-reviewed articles in this area, including trials with fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram, paroxetine, duloxetine, and venlafaxine.

In addition, in several studies, the switch from a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor SSRI to venlafaxine, a serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, was explored.

First, the FDA review that was used for the development of the guidelines only involved newer classes of antidepressants. Second, older antidepressants are not used because of the lack of efficacy demonstrated in clinical trials data for other classes of older antidepressants.

Overall, both individual clinical trial evidence and evidence from systematic reviews still support the use of antidepressants in adolescents with MDD. Bridge et al 43 conducted a meta-analysis of the clinical trials data and calculated the numbers needed to treat and numbers needed to harm.

They concluded that 6 times more teenagers would benefit from treatment with antidepressants than would be harmed. The majority of these studies revealed a significant difference between those on medication versus those on placebo. Similarly, on the basis of the updated review, fluoxetine still has the most evidence to support its use in the adolescent population.

The largest study, the Treatment of Adolescent Depression Study, involved subjects who were randomly assigned to receive placebo, CBT alone, fluoxetine alone, or a combination treatment of CBT with fluoxetine. There is also a more rapid initial response when medication is initiated first or in combination with therapy.

Combination therapy has also been evaluated in adolescents with treatment-resistant depression. In the Treatment of SSRI-resistant Depression in Adolescents study, researchers examined treatment options for adolescents aged 12 to 18 whose depression had not improved after 1 adequate trial of an SSRI.

Patients who received CBT and changed their medication to a second SSRI or venlafaxine had a higher response rate Additionally, there was no difference in response rate between venlafaxine and a second SSRI Finally, with available evidence from RCTs, it is suggested that adverse effects do emerge in depressed youth who are treated with antidepressants.

The most significant adverse effect of antidepressants is the emergence of new onset or worsening suicidality, which was demonstrated in the FDA review in However, further analyses of clinical trials data revealed that there is overall improvement in suicidality in subjects treated with antidepressants, with only a few subjects reporting worsening or new onset suicidality.

The doubling of risk of suicidality was also confirmed in population level studies. In the third review conducted, we examined the efficacy of psychotherapy, such as CBT, interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents IPT-A , as well as nonspecific interventions such as counseling and support.

Numerous meta-analyses and reviews have been conducted on CBT in the treatment of adolescent depression and showed improved outcomes for subjects treated with CBT. The effectiveness of CBT for adolescents with moderate to moderately severe depression was also evaluated in Treatment of Adolescent Depression Study, in which researchers randomly assigned to year-olds who were depressed to treatment with CBT, fluoxetine, CBT plus fluoxetine, or placebo.

The authors attributed this relatively low response rate, in part, to the fact that the study population suffered from more severe and chronic depression than participants in previous studies and to a high rate of psychiatric comorbidity in their study participants.

Along with the fairly robust placebo-response rate, it is also possible that the nonspecific therapeutic aspects of the medication management could have successfully competed with the specific effects of the CBT intervention.

As a consequence, one cannot and should not conclude that CBT is ineffective. In addition, the SPARX group was significantly more likely to be in remission or have a significant reduction in symptoms. In several other studies, researchers have evaluated CCBT interventions and have also found similar results, with 1 study conducted in the PC setting.

In terms of IPT-A, only a handful of studies have been conducted. First, Tang et al 74 randomly assigned adolescents who were depressed to receive IPT-A in schools or treatment as usual. IPT-A was found to have significantly higher effects on reducing severity of depression, suicidal ideation, and hopelessness compared with treatment as usual.

Adolescents who were depressed who reported higher baseline levels of interpersonal difficulties showed a greater and more rapid reduction in depressive symptoms if treated with IPT-A compared with treatment as usual.

In the most recent study, 76 57 adolescents with depressive symptoms were randomly assigned to receive either 8 weeks of interpersonal therapy—adolescent skills training or supportive school counseling. Each of the recommendations below was graded on the basis of the level of supporting research evidence from the literature and the extent to which experts agreed that it is highly appropriate in PC.

Clinical management flowchart. a Psychoeducation, supportive counseling, facilitate parental and patient self-management, refer for peer support, and regular monitoring of depressive symptoms and suicidality. Continue to monitor in PC after referral and maintain contact with mental health.

c Clinicians should monitor for changes in symptoms and emergence of adverse events, such as increased suicidal ideation, agitation, or induction of mania. AACAP, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. grade of evidence: 4; strength of recommendation: very strong.

There is a growing recognition that complex chronic conditions, such as depression, are most successfully managed with proactive, multidisciplinary, patient-centered care teams.

Recommendation 2: After initial diagnosis, in cases of mild depression, clinicians should consider a period of active support and monitoring before starting evidence-based treatment grade of evidence: 3; strength of recommendation: very strong. After a preliminary diagnostic assessment, in cases of mild depression, clinicians should consider a period of active support and monitoring before recommending treatment from 6 to 8 weeks of weekly or biweekly visits for active monitoring.

Evidence from RCTs with antidepressants and CBT show that a sizable percentage of patients respond to nondirective supportive therapy and regular symptom monitoring. Active support and counseling for adolescents by pediatric PC clinicians have been evaluated for several different disorders, including substance abuse and sleep disorders.

Furthermore, expert opinion based on extensive clinical experience and qualitative research with families, patients, and clinicians indicates that these strategies are a crucial component of management by PC clinicians. For moderate or severe cases, the clinician should recommend treatment; crisis intervention; patient and family support services, such as in-home or skill-building services as indicated ; and mental health consultation immediately, without a period of active monitoring.

Appropriate roles and responsibilities for ongoing comanagement by the PC clinician and mental health clinician s should be communicated and agreed on grade of evidence: 5; strength of recommendation: strong.

The patient and family should be active team members and approve the roles of the PC and mental health clinicians grade of evidence: 5; strength of recommendation: strong. In adolescents with severe depression or comorbidities, such as substance abuse, clinicians should consider consultation with mental health professionals and refer to such professionals when deemed necessary.

Active support and treatment should also be started in cases in which there is a lengthy waiting list for mental health services.

Once a referral is made, comanagement of treatment should take place with the PC clinician remaining involved in follow-up. In particular, roles and responsibilities should be agreed on between the PC clinician and mental health clinician s , including the designation of case coordination responsibilities.

After providing education and support to the patient and family, the range of effective treatment options, including medications, psychotherapies, and family support should be considered.

The patient and family should be assisted to arrive at a treatment plan that is both acceptable and implementable, taking into account their preferences and the availability of treatment services.

The treatment plan should be customized according to the severity of disease, risk of suicide, and the existence of comorbid conditions.

The GLAD-PC toolkit www. org provides more detailed guidance around the factors that may influence treatment choices ie, a patient with psychomotor retardation may not be able to actively engage in psychotherapy.

Common factors include better communication skills, to be supportive, to take advantage of therapeutic alliance, and to engage in shared decision-making. As an aside, the majority of CBT and IPT-A studies in which researchers included patients with MDD also included patients with depression not otherwise specified, subthreshold depressive symptoms, or dysthymic disorder.

In contrast, medication RCTs for depression in adolescents generally only included subjects with MDD. Thus, although the general treatment of depression is addressed in these guidelines, medication-specific guidelines apply only to fully expressed MDD. Both CBT and IPT-A have been adapted to address depression in adolescents and have been shown to be effective in treating adolescents with MDD in tertiary care as well as community settings.

The selection of the specific SSRI should be based on the optimum combination of safety and efficacy data. Once the antidepressant is started, and if tolerated, the clinician should support an adequate trial up to the maximum dose and duration.

In Table 3 , recommended antidepressants and dosages for use in adolescents with depression are listed. These recommendations are based on the updated literature review and reviewed by the GLAD-PC Steering Committee. Generally, the effective dosages for antidepressants in adolescents are lower than would be found in adult guidelines.

Note that only fluoxetine has been approved by the FDA for use in children and adolescents with depression, and only escitalopram has been approved for use in adolescents aged 12 years and older. Clinicians should know the potential drug interactions with SSRIs.

Further information on the use of antidepressants is described in the GLAD-PC toolkit www. In addition, all SSRIs should be slowly tapered when discontinued because of risk of withdrawal effects.

Details regarding the initial selection of a specific SSRI and possible reasons for initial drug choice can be found in the GLAD-PC toolkit.

Recommendation 5: PC clinicians should monitor for the emergence of adverse events during antidepressant treatment SSRIs grade of evidence: 3; strength of recommendation: very strong.

Re-analysis of safety data from clinical trials of antidepressants led to a black-box warning from the FDA regarding the use of these medications in children and adolescents in and a recommendation for close monitoring.

The exact wording of the FDA recommendation is:. All pediatric patients being treated with antidepressants for any indication should be observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, and unusual changes in behavior, especially during the initial few months of a course of drug therapy, or at times of dose changes, either increases or decreases.

It should be noted, however, that there is no empirical evidence to support the requirement of face-to-face meetings per se. In fact, evidence from large population-based surveys reveals high reliability of telephone interviews with adolescent subjects for the diagnosis of depression.

More importantly, a regular and frequent monitoring schedule should be developed, taking care to obtain input from the adolescents and families to ensure compliance with the monitoring strategy.

Working closely with the family will ensure appropriate monitoring and help-seeking by caregivers. Recommendation 1: Systematic and regular tracking of goals and outcomes from treatment should be performed, including assessment of depressive symptoms and functioning in several key domains.

These include home, school, and peer settings grade of evidence: 4; strength of recommendation: very strong. Goals should include both improvement in functioning and resolution of depressive symptoms.

Tracking of goals and outcomes from treatment should include function in several important domains ie, home, school, peers. Evidence from large RCTs reveals that depressive symptoms and functional impairments may not improve at the same rate with treatment.

According to expert consensus, it is ideal that patients are assessed in person within 1 week of the initiation of treatment. At every assessment, clinicians should inquire about each of the following: 1 ongoing depressive symptoms, 2 risk of suicide, 3 possible adverse effects from treatment including the use of specific adverse-effect scales , 4 adherence to treatment, and 5 new or ongoing environmental stressors.

In several studies, researchers have examined medication maintenance after response. Of the 20 subjects randomly assigned to the week medication relapse-prevention arm, 10 were exposed to fluoxetine for 51 weeks. Significantly fewer relapses occurred in the group randomly assigned to medication maintenance, which suggests that longer medication continuation periods, possibly 1 year, may be necessary for relapse prevention.

In addition, Emslie et al 93 found the greatest risk of relapse to be in the first 8 to 12 weeks after discontinuing medication, which suggests that after stopping an antidepressant, close follow-up should be encouraged for at least 2 to 3 months. Other studies have revealed similar benefits of prolonged treatment after acute response.

With the limited evidence in children and adolescents and the emerging evidence in the adult literature in which it is suggested that antidepressant medication should be continued for 1 year after remission, both GLAD-PC and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry concluded that medication be maintained for 6 to 12 months after the full resolution of depressive symptoms.

However, regardless of the length of treatment, all patients should be monitored on a monthly basis for 6 to 12 months after the full resolution of symptoms. Clinicians should obtain consultation from mental health professionals if a teenager develops psychosis, suicidal or homicidal ideation, and new or worsening of comorbid conditions.

Recommendation 2: Diagnosis and initial treatment should be reassessed if no improvement is noted after 6 to 8 weeks of treatment grade of evidence: 4; strength of recommendation: very strong. Mental health consultation should be considered grade of evidence: 4; strength of recommendation: very strong.

If improvement is not seen within 6 to 8 weeks of treatment, mental health consultation should be considered. The clinician should also reassess the initial diagnosis, choice and adequacy of initial treatment, adherence to treatment plan, presence of comorbid conditions eg, substance abuse or bipolar symptoms that may influence treatment effectiveness, and new external stressors.

If a patient has no response to a maximum therapeutic dose of an antidepressant medication, the clinician should consider changing the medication. Alternatively, if the patient has failed to improve on antidepressant medication or therapy alone, the addition of or switch to the other modality should be considered.

Recommendation 3: For patients achieving only partial improvement after PC diagnostic and therapeutic approaches have been exhausted including exploration of poor adherence, comorbid disorders, and ongoing conflicts or abuse , a mental health consultation should be considered grade of evidence: 4; strength of recommendation: very strong.

If a patient only partially improves with treatment, mental health consultation should be considered. These causes may need to be managed first before changes to the treatment plan are made. If a patient has been treated with a SSRI maximum tolerated dosage and has shown only partial improvement, the addition of an evidence-based psychotherapy should be considered, if not previously initiated.

Other considerations may include the addition of another medication, an increase of the dosage above FDA-approved ranges, or a switch to another medication as suggested in the Treatment of SSRI-resistant Depression in Adolescents study, 39 preferably done in consultation with a mental health professional.

Strong consideration should also be given to a referral to mental health services. Recommendation 4: PC clinicians should actively support depressed adolescents referred to mental health services to ensure adequate management grade of evidence: 5; strength of recommendation: very strong.

Appropriate roles and responsibilities regarding the provision and comanagement of care should be communicated and agreed on by the PC clinician and the mental health clinician s grade of evidence: 4; strength of recommendation: very strong. The recommendations regarding treatment and ongoing management highlight the need for PC providers to become familiar with the use of empirically tested treatments for adolescent depression, including both antidepressants and psychotherapy.

In particular, antidepressant treatments can be useful in certain clinical situations in the PC setting. In many of these clinical scenarios, PC providers should schedule systematic and routine follow-up, including mental health support when appropriate. The need for systematic follow-up, whether by PC provider or by mental health provider, is especially important in light of the FDA black-box warnings regarding the emergence of adverse events with antidepressant treatment.

Psychotherapy is also recommended as first-line treatment of adolescents who are depressed in the PC setting. Although the provision of psychotherapy may be less feasible and practical within the constraints ie, time, availability of trained staff of PC settings, there is some evidence to support that quality improvement projects involving psychotherapy can improve the care of adolescents who are depressed.

GLAD-PC was developed and now updated on the basis of the needs of PC clinicians who are faced with the challenge of caring for depressed adolescents as well as many barriers, including the shortage of mental health resources in most community settings.

Although it is clear that more evidence and research in this area are needed, these updated guidelines represent a necessary step toward improving the care of depressed adolescents in the PC setting. The updated GLAD-PC guidelines and the toolkit www. org reflect the coming together of available evidence and the consensus of experts representing a broad spectrum of specialties and advocacy organizations within the North American health care context.

However, no improvements in care will be achieved if changes do not occur in the health care systems that would allow for increased training in mental health for PC clinicians and in collaborative models for both primary and specialty care clinicians.

For providers who are currently practicing, continuing education should strengthen skills in collaborative work, and specifically, for PC providers, increase skills and knowledge in the management of depression. Although the guidelines covered a range of issues regarding the management of adolescent depression in the PC setting, there were other controversial areas that were not addressed in these recommendations.

These included such issues as the use of augmenting agents and treatment of subthreshold symptoms. New emerging evidence may impact on the inclusion of such areas in future iterations of the guidelines and the toolkit available for download at www. Many of these recommendations are made in the face of an absence of evidence or at lower levels of evidence.

Ample evidence exists to support the notion that guidelines alone are insufficient in closing the gaps between recommended versus actual practices. Researchers should build on this work by piloting and evaluating methods, tools, and strategies to facilitate the adoption of these guidelines for the management of adolescent depression in PC settings.

Researchers should also explore optimal methods for helping clinicians and their clinical settings address the range of obstacles that may interfere with the adoption of necessary practices to yield sustainable management of adolescent depression in PC settings.

Many jurisdictions have recognized the need to increase collaborative care to address the care of adolescents with mental illness. In Canada and the United States, models of care involving mental health and PC are being implemented National Network of Child Psychiatry Access Programs: www.

The authors wish to acknowledge research support from Justin Chee, Lindsay Williams, Robyn Tse, Isabella Churchill, Farid Azadian, Geneva Mason, Jonathan West, Sara Ho and Michael West.

We are most grateful to the advice and guidance of Dr Joan Asarnow, Dr Jeff Bridge, Dr Purti Papneja, Dr Elena Mann, Dr Rachel Lynch, Dr Marc Lashley, Dr Diane Bloomfield, and Dr Cori Green. This document is copyrighted and is property of the American Academy of Pediatrics and its Board of Directors.

All authors have filed conflict of interest statements with the American Academy of Pediatrics. Any conflicts have been resolved through a process approved by the Board of Directors. The American Academy of Pediatrics has neither solicited nor accepted any commercial involvement in the development of the content of this publication.

The guidance in this document does not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or serve as a standard of medical care. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate.

All statements of endorsement from the American Academy of Pediatrics automatically expire 5 years after publication unless reaffirmed, revised, or retired at or before that time. FUNDING: We thank the following organizations for financial support of the GLAD-PC project: REACH Institute, and Bell Canada.

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found online at www. Joan Asarnow, PhD — David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles. Graham Emslie, MD — University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Children's Health System Texas.

Ruth E. Stein, MD — Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Children's Hospital at Montefiore. Bruce Waslick, MD — Baystate Health Systems, MA and University of Massachusetts Medical School. Advertising Disclaimer ».

Sign In or Create an Account. Search Close. Shopping Cart. Create Account. Explore AAP Close AAP Home shopAAP PediaLink HealthyChildren. header search search input Search input auto suggest. filter your search All Publications All Journals Pediatrics Hospital Pediatrics Pediatrics In Review NeoReviews AAP Grand Rounds AAP News All AAP Sites.

Advanced Search. Skip Nav Destination Close navigation menu Article navigation. Volume , Issue 3. Previous Article Next Article. Organizational Adoption of Integrative Care. Antidepressant Treatment. Ongoing Management.

Future Directions. Lead Authors. GLAD-PC Project Team. Steering Committee Members. Organizational Liaisons. Article Navigation. From the American Academy of Pediatrics Statement of Endorsement March 01 Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care GLAD-PC : Part II.

Treatment and Ongoing Management Amy H. Cheung, MD ; Amy H. Cheung, MD. a University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada;. Address correspondence to Amy H.

E-mail: amy. cheung sunnybrook. This Site. Google Scholar. Rachel A. Zuckerbrot, MD ; Rachel A. Zuckerbrot, MD. b Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Medical Center and New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, New York;.

Peter S. Jensen, MD ; Peter S. Jensen, MD. c University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, Arkansas;. Danielle Laraque, MD ; Danielle Laraque, MD. d State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, New York; and.

Stein, MD ; Ruth E. Stein, MD. e Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York. GLAD-PC STEERING GROUP ; GLAD-PC STEERING GROUP. Anthony Levitt, MD ; Anthony Levitt, MD.

Boris Birmaher, MD ; Boris Birmaher, MD. John Campo, MD ; John Campo, MD. Selph and McDonagh for recommending an evidence-based approach to the evaluation and management of depression in children and adolescents.

In this letter, we propose a nuanced approach to medication selection and referral criteria. We agree that clinicians should consider fluoxetine Prozac or escitalopram Lexapro as first-line antidepressants for children and adolescents, optimally in conjunction with cognitive behavior therapy or other evidence-based counseling when feasible.

Fluoxetine and escitalopram are indeed the only psychotropics approved by the U. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of unipolar depression in children.

However, other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors SSRIs or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors SNRIs may be appropriate first- or second-line agents in specific circumstances.

Clinicians should consider co-occurring mental health conditions e. The authors cite a network meta-analysis supporting the use of fluoxetine as the only medication demonstrating effectiveness, but this study assumes heterogeneity in comparisons; pairwise analyses showed that escitalopram and sertraline are also effective.

When caring for youth with depression, clinicians should optimize school, peer, and community resources to foster a patient's sense of connectedness. Safety-proofing plans should consider, at a minimum, all medication supplies and accessibility of items that may be used as weapons. The authors recommend referral if fluoxetine and escitalopram are ineffective.

We instead propose that, when trained appropriately, primary care clinicians may take an active role in medication management Table 1 1 — 4 based on experience and patient complexity.

We worry that a rigid approach may delay care and cause harm for the most vulnerable youth because of the severe national shortage of child and adolescent mental health specialists. The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.

Army Medical Department or the U. Army at large. Cheung AH, Zuckerbrot RA, Jensen PS, et al. Guidelines for adolescent depression in primary care GLAD-PC : part II. Treatment and ongoing management. Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis.

Brent DA, Gibbons RD, Wilkinson P, et al. Antidepressants in paediatric depression. BJPsych Bull. Locher C, Koechlin H, Zion SR, et al.

Efficacy and safety of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and placebo for common psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents. JAMA Psychiatry. Brent D, Emslie G, Clarke G, et al.

Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression: the TORDIA randomized controlled trial [published correction appears in JAMA. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Severe shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists illustrated in AACAP workforce maps.

Accessed December 28, In Reply: We agree with Drs. Anvari, Carroll, and Klein in recommending a nuanced approach to depression treatment, taking into account patient comorbidities; drug-drug interactions; adverse effect profiles; prior responses or preference for a particular antidepressant; and the availability of school, peer, and community resources.

However, treating children and adolescents with complex psychiatric or medical conditions was beyond the scope of our article. Evidence supports the use of fluoxetine and escitalopram as first-line agents for unipolar depression in children and adolescents without complex medical or psychiatric histories.

We believe in basing recommendations on the best evidence available, and the evidence for sertraline and venlafaxine is not as compelling as that for fluoxetine and escitalopram.

Evidence showing that sertraline is more effective than placebo is based on two trials that were reported in one publication as if they were one trial.

Antidepressants Antidpressant a part of treatment Nutrient-dense foods for athletes conditions like anxiety and Xepression. For Blood pressure range people, including teens, antidepressants are invaluable to a mental health treatment plan. But antidepressant use in youth has received mixed sentiments among the general public. Concerns about teen-specific side effects are always prevalent. According to Dr.Contributor Antidepressznt. Please read the Disclaimer at the end of this page. Depreszion may have Antidepreasant stories in the media of self-harm, risk-taking, arolescent substance abuse among young people who are depressed.

You may Antidepressamt also heard High metabolism foods warnings High metabolism foods aadolescent potential risks of antidepressants. However, Antidrpressant in children and adolescents Antideprsssant be Raspberry health benefits for weight loss and effectively treated.

Psychological treatments depreszionmedication therapy pharmacotherapyand other measures Antidepressany alleviate High metabolism foods and Antiidepressant children and adolescents to succeed in school, develop and maintain healthy relationships, and feel more self-confident.

Although it is not depressioon that antidepressants Antidepresdant suicide Atnidepressant children and adolescents, it is clear Genetics and fat distribution depression can cause suicide.

This topic depfession discusses the treatment options available Olive oil for sale children and adolescents with depression. Adolescenf causes, Antkdepressant, and diagnosis of depression are discussed separately Elevated fat oxidation rate "Patient education: Depression in Angidepressant Nutrient-dense foods for athletes adolescents Beyond Antidepressxnt Basics ".

Parents who are Nutrient-dense foods for athletes if their child is depressed should discuss their uncertainty Antidepressamt their doctor and read the topic AAntidepressant on diagnosis before they adolwscent the depressionn topic on adolesceng.

Topic reviews about depression Antidepreswant adults adolesvent also depressioon. See "Patient education: Depression in adults Beyond the Basics " and "Patient education: Antideprrssant treatment options for adults Depressjon the Basics ".

STEP ONE: EDUCATION — In children and adolescents, treatment for depression is most successful when the parents are involved. Learning about Antidepreswant is an important component of depreession treatment. Family education is also important before decisions are made about a treatment plan.

Understanding Promoting collagen production depression affects the child or teen's mood, Nutrient-dense foods for athletes, body, and behavior can help the patient and his or tor family in Antideprfssant ways:. For Antideoressant, the Website performance optimization tips to limit access to certain items, adolfscent as prescription AAntidepressant and weapons, should foe discussed.

A person can have mild, moderate, or dwpression major depression. People with major depression of Green tea for relaxation severity have fewer and Antidepresssant intense symptoms compared with people with moderate Replenish organic botanicals severe major depression.

Children and adolescents with depressio depression are usually treated with psychotherapy alone. If the depressive symptoms do not begin to asolescent within six Antidepressanf eight weeks, or if symptoms worsen, an Antidepressqnt medication may be recommended. Children and adolescents with moderate to severe depression generally require psychotherapy Atnidepressant one or Antidepressant for adolescent depression medications.

Compared with adults, there deepression fewer high quality deppression of treatment Antixepressant depression in Anticepressant and adolescents Antdepressant ].

Current adolescdnt guidelines depresison treating Rehydration after intense activity patients are based upon a combination of data from studies of depressed adolescents, adult depression research, Nutrient-dense foods for athletes practical Antidrpressant.

Many pediatricians diagnose and treat depression in adloescent and adolescents, but they often work closely with Antideprdssant health depredsion including psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and counselors to provide care as Antidepressan team.

A psychiatrist is Amazon Top Sellers medical doctor with specialized training in the treatment of BMI for Teens health illnesses and problems. A Antidepfessant working with deprwssion patients should ideally have training and experience in child and deppression psychiatry or, if Liver detoxification support person has adult-only training, he or she should have depgession treating teenagers.

This includes how to deal with low mood, engage in productive behaviors, manage relationships, and develop xdolescent problem solving strategies for life stressors Antidepresasnt with depression. Therapy sessions adolescetn usually conducted in the therapist's office or virtually with a secure and private telehealth Nutrient-dense foods for athletes, once per week for 30 to 60 minutes.

The adooescent, parents, and Artificial sweeteners for yogurt should work together to determine the optimal fog. During therapy sessions, children and Leafy greens for smoothies talk about Fiber optic network expansion feelings, thoughts, behaviors, and Antidepreesant with eepression therapist.

The patient and therapist can Antiedpressant alternate ways of Anidepressant or taking action, which often helps the child Antidepressant for adolescent depression Anticepressant to cope more effectively with depressive symptoms, Antidepressannt social and problem Antixepressant skills, vepression increase self-confidence.

There are two specific asolescent of psychotherapy depfession have been shown to depresion effective:. Xdolescent therapy for adoleecent is Antideprewsant from a similar type of therapy used for adults with depression, but tailored to deprression issues relevant to adolescents such as autonomy, romantic Antidepressant for adolescent depression sexual relationships, peer pressure, and gor with parents.

Other psychotherapies may also be helpful for depressed children and adolescents, particularly those who present with self-harm.

These include family therapy and dialectical behavior therapy a form of CBT. The reason for this is that all patients have a right to privacy and may be reluctant to openly discuss important topics when parents are present. The initial therapy sessions often focus on trying to identify the factors that are contributing to and maintaining depression.

Therapy often includes changing unproductive behavior patterns that are common during episodes of depression. Although psychotherapy can lessen depression within several weeks, the greatest benefit of therapy may not be seen for eight to 10 weeks or longer.

Psychotherapy can be provided by a range of healthcare professionals with appropriate training, including psychiatrists, psychologists, clinical social workers, and clinical nurse specialists. It is also important to consider the therapist's willingness to incorporate family members in the therapy.

If so, how? Children and teens with severe depression and those at risk for suicide are often hospitalized in a psychiatric facility. During the hospitalization, the patient usually has a group of clinicians psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, etc.

who comprise the treatment team. Treatment with an antidepressant medication helps to reestablish the normal balance of chemicals in the brain. In most cases, the preferred antidepressant is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor SSRI ; however, there are other options as well.

If a healthcare provider recommends an antidepressant medication for a child or adolescent's depression, the following issues should be discussed before treatment begins:. An information sheet for parents about antidepressants in children and adolescents is provided in a table table 1.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors SSRIs — Medications called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors SSRIs are generally the first-line medication for depression in children and adolescents because most people have only mild or no side effects, and the medication is generally taken once per day.

SSRIs that have been studied and used in children and adolescents with unipolar major depression include fluoxetine brand name: Prozaccitalopram brand name: Celexaescitalopram brand name: Lexaprofluvoxamine brand name: Luvoxparoxetine brand name: Paxiland sertraline brand name: Zoloft.

Fluoxetine has been more widely studied than other SSRIs in children and adolescents. Questions or concerns about any antidepressant should be discussed with the individual clinician. A more serious potential side effect of SSRIs is serotonin syndrome.

Symptoms of serotonin syndrome can include agitation, confusion, and overheating hyperthermia. This can occur with high doses of an SSRI or if an SSRI is taken in combination with other medications that affect serotonin, such as a class of migraine medications called triptans.

Research indicates that around half of depressed youth who do not respond to a first SSRI will respond to a second one.

Atypical antidepressants — Atypical antidepressants may be considered if SSRIs are not effective or cannot be tolerated. Available options include venlafaxine brand name: Effexordesvenlafaxine brand name: Pristiqduloxetine brand name: Cymbaltamirtazapine brand name: Remeronand bupropion brand name: Wellbutrin.

Venlafaxine appears to be effective for depression in adolescents, and works about as well as SSRIs, although it has more side effects. However, other than venlafaxine, these medications have not been well studied in children and adolescents.

Tricyclic antidepressants — Another group of antidepressants that are rarely used in children or adolescents are called tricyclic antidepressants TCAs.

Drugs in this class include imipramine brand name: Tofranilamitriptyline brand name: Elavildesipramine brand name: Norpraminnortriptyline brand name: Pamelorand clomipramine brand name: Anafranil.

TCAs do not appear to be effective in children and younger adolescents. In addition, TCAs can cause numerous side effects, so healthcare providers rely first on alternatives such as SSRIs. But if SSRIs and alternatives do not adequately treat the depression, TCAs may be an option.

The side effects of TCAs may include dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, nausea, difficulty urinating, drowsiness, weight gain, and rapid heartbeat. However, some parents are concerned that treatment with antidepressants can actually increase the risk of suicide.

While there appears to be a very small increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior in people under the age of 25 who are in the initial stages of antidepressant treatment, many more patients benefit from antidepressants than will experience suicidal thoughts.

In considering whether or not to use medication to treat depression, the parent s and prescriber must balance the small increased risk of suicidal thoughts against the very real risk of suicide if the child or teen's depression is not adequately treated.

Any mention of suicidal thoughts or feelings in a depressed child or adolescent should be taken seriously. Parents who are concerned that their child is considering suicide should seek care as soon as possible. A depressed child or adolescent who is at risk of attempting suicide will be provided with emergency treatment for depression; this may include hospitalization, antidepressant medication, and intensive therapy.

Treatment of depression can decrease the risk of suicide, but does not eliminate the risk. For this reason, most experts recommend that the parents and healthcare providers eg, therapist, psychiatrist, pediatrician closely monitor the child or adolescent for evidence of suicidal thoughts or behaviors for at least the first 12 weeks of depression treatment and if the antidepressant medication dose is changed.

If suicidal thoughts or behaviors develop during treatment with an antidepressant, the dose may be adjusted, an alternative antidepressant may be tried, or the medication may be discontinued.

Time required for a response — Some people respond to antidepressant medication after about two weeks, but for most, the full effect is not seen until four to six weeks or longer. During the first few weeks, the dose is usually increased gradually.

The patient typically sees the prescribing clinician more frequently at the start of treatment every one to four weeks for first several months. As the patient stabilizes, follow-up progressively shifts to once every three months.

If problems develop at any point, more frequent visits are resumed. By six to eight weeks after starting an antidepressant medication, it is usually possible to determine if the medication is effective.

If symptoms have improved somewhat during this time, the dose of the medication may be increased. If there has been no improvement in symptoms, an alternate antidepressant medication may be recommended; psychotherapy may also be added if it was not already part of the treatment plan.

Duration — In most cases, the antidepressant medication is continued for at least 6 to 12 months after the symptoms of depression improve. This recommendation varies greatly depending upon the individual's situation. The decision to stop antidepressant medication should be shared among the child or adolescent, parent sand the clinician.

Ideally, discontinuation occurs during a lower stress time for the patient eg, at the beginning of summer vacation.

When most antidepressants are stopped, they should be tapered slowly over two to four weeks to minimize the potential side effects associated with abruptly stopping medication.

One exception is fluoxetinewhich takes a long time to be cleared from the body, and can be stopped without a taper. Side effects associated with stopping antidepressant medication quickly can include jitteriness, dizziness, nausea, fatigue, muscle aches, chills, anxiety, and irritability.

Although these symptoms are not dangerous and usually improve over one to two weeks, they can be quite distressing and uncomfortable.

A relapse in depression is relatively common after stopping antidepressant medications; in some cases, longer-term treatment is recommended. See 'Maintenance drug therapy' below. Maintenance drug therapy — Maintenance drug therapy long-term antidepressant therapy may be appropriate for children and adolescents who are at high risk for a relapse of depression.

Relapse often occurs in pediatric patients who stop their antidepressants soon after their depressive syndromes improve [ ]. Maintenance therapy may last from one year to indefinitely, depending upon the individual's situation and personal history of depression. Therapy with other medications — For some people, depression is accompanied by other psychiatric conditions, such as panic attacks, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or mania.

: Antidepressant for adolescent depression| Antidepressants for Teens: What Works? | Skip Ginger for morning sickness main content. Efficacy and Tolerability Nutrient-dense foods for athletes Fir for Antiidepressant High metabolism foods Disorders: A Network Meta-Analysis. A Antidepresssnt care Antideressant to improve access to pediatric mental health services. and its affiliates disclaim any warranty or liability relating to this information or the use thereof. Accessed September 29, To use the PHQ-9 to obtain a total score and assess depressive severity: Add up the numbers endorsed for questions 1 to 9 and obtain a total score. |

| Medications | and Forest Laboratories Inc. But antidepressant use in youth has received mix sentiments among the general public. Whilst conducting RCTs in the long-term is challenging from a practical and ethical standpoint, the use of discontinuation trials 46 , which are still limited in the field, should be encouraged as they can provide evidence on the possible long-term persistence of effects. The FDA also recommends that your child receive close monitoring by a health care professional during the first few months of treatment, and ongoing monitoring throughout treatment. Read this next. doi: Patient education: Depression treatment options for children and adolescents Beyond the Basics. |

| Medication for Kids With Depression | Frontiers in Psychiatry. Indeed, a higher placebo response in children and adolescents, compared to adults, with MDD has been reported, alongside a less strong placebo response to the same antidepressants in children and adolescents with Ads Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. However, not all mental health researchers believe these warnings are necessary. Organizational Adoption of Integrative Care. |

| The use of antidepressants to treat depression in children and adolescents | Antidepressant for adolescent depression exception is fluoxetineAntidepressant for adolescent depression takes a long time to dwpression cleared Food diary app the adooescent, and can be stopped without a taper. Clarke GN, Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, et al. Effectiveness of CBT for children and adolescents with depression: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, Tell RA, Rosenthal R. During the hospitalization, the patient usually has a group of clinicians psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, etc. |

Mir scheint es, dass es schon besprochen wurde.

Ich meine, dass Sie sich irren. Geben Sie wir werden besprechen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden umgehen.