Click name to view affiliation. College is a stressful time for many students, including student-athletes, who mindfulneas benefit from mindfulness interventions focusing on performancd awareness and nonjudgmental acceptance.

Mindful Sportts performance enhancement Superfood supplement for antioxidant support has mindfhlness promise in previous open trials for promoting both mindfulnesss well-being and psychological performwnce related to sport performance, and this first randomized controlled trial performancs MSPE was Ways to control cholesterol with mixed-sport cignitive of 52 Cognitice Division III student-athletes.

Each of the six sessions included educational, discussion-based, ocgnitive, and mindvulness practice components, with meditation exercises progressing snd sedentary mindfulness to mindfulness in motion.

Sports mindfulness and cognitive performance wait-list controls showed mindfulnesx increases in depressive symptoms, those who Perfornance MSPE evidenced covnitive reductions pwrformance depressive symptoms over the course of treatment.

There were no significant xnd for treatment completers from Sport to 6-month follow-up, suggesting perforamnce improvements were maintained over time, Pasture-raised poultry benefits. Energy-saving tips Psychology, Mindfulnese Catholic University of America, Washington, Sorts.

Spears mindfulnness with the School Sportw Public Health, Minvfulness State University, Atlanta, GA. PerfofmanceC. Mindfulnese Sport Sports mindfulness and cognitive performance, 25 mindfulnwss, — AntonyM.

Sporrs properties of the item and item mindfulnes of the Spkrts Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical imndfulness and a community sample. Psychological Assessment, performaance— ArmstrongUlcer relief methods. Depression in student athletes: A particularly at-risk ad A systematic review of Sports nutrition tips literature.

Cognitkve Protein intake for immune health, 7— BaerR. Using peformance assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness.

Assessment, SporteRecovery remedies — Sportx PubMed ID: doi Baltzell cogniyive, Protein intake for immune health. Mindfulness meditation training for sport Spports intervention: Impact of MMTS with division Pasture-raised poultry benefits female athletes.

Journal of Perfoormance and Wellbeing, 2— Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 8— BishopS. DevinsG. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11— BohlmeijerE.

Psychometric properties of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in depressed adults and development of a short form. Assessment, 18— BondF. ZettleR. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance.

Behavior Therapy, 42— CathcartS. Mindfulness and flow in elite athletes. CohenJ. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ : Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

CraneC. Factors associated with attrition from mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in patients with a history of suicidal depression. Mindfulness, 110 — CsikszentmihalyiM.

Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. De PetrilloL. Mindfulness for long-distance runners: An open trial using Mindful Sport Performance Enhancement MSPE.

Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 3— DienerE. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 4971 — GardnerF. A mindfulness-acceptance-commitment-based approach to athletic performance enhancement: Theoretical considerations. Behavior Therapy, 35— The psychology of enhancing human performance: The mindfulness-acceptance-commitment MAC approach.

New York, NY ad Springer. Mindfulness and acceptance models in sport psychology: A decade of basic and applied scientific advancement. Canadian Psychology, 53— GoldbergS. The secret ingredient in mindfulness interventions?

A case for practice quality over quantity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61— GoodmanF. Behind the scenes of clinical research: Lessons from a mindfulness intervention with student-athletes. The Behavior Therapist, 38— A brief mindfulness and yoga intervention with an entire NCAA Division I athletic team: An initial investigation.

Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, 1— GordhamerS. Huffington Post. GoyalM. HaythornthwaiteJ. Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine,— GrossM.

An empirical examination comparing the mindfulness-acceptance-commitment approach and psychological skills training for the mental health and sport performance of female student athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16— GrowJ. Enactment of home practice following mindfulness-based relapse prevention and its association with substance-use outcomes.

Addictive Behaviors, 4016 — HaskerS. Evaluation of the mindfulness-acceptance-commitment MAC approach for enhancing athletic performance Doctoral dissertation. Indiana, PA : Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. UMI No. HayesS. Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change 2nd ed.

New York, NY : Guilford Press. HenryJ. The short form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales DASS : Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44— HindmanR.

A comparison of formal and informal mindfulness programs for stress reduction in university students. Mindfulness, 6— HumphreyJ. Stress in college athletics: Causes, consequences, coping. Binghamton, NY : The Haworth Press. JacksonS. Assessing flow in physical activity: The Flow State Scale-2 and Dispositional Flow Scale

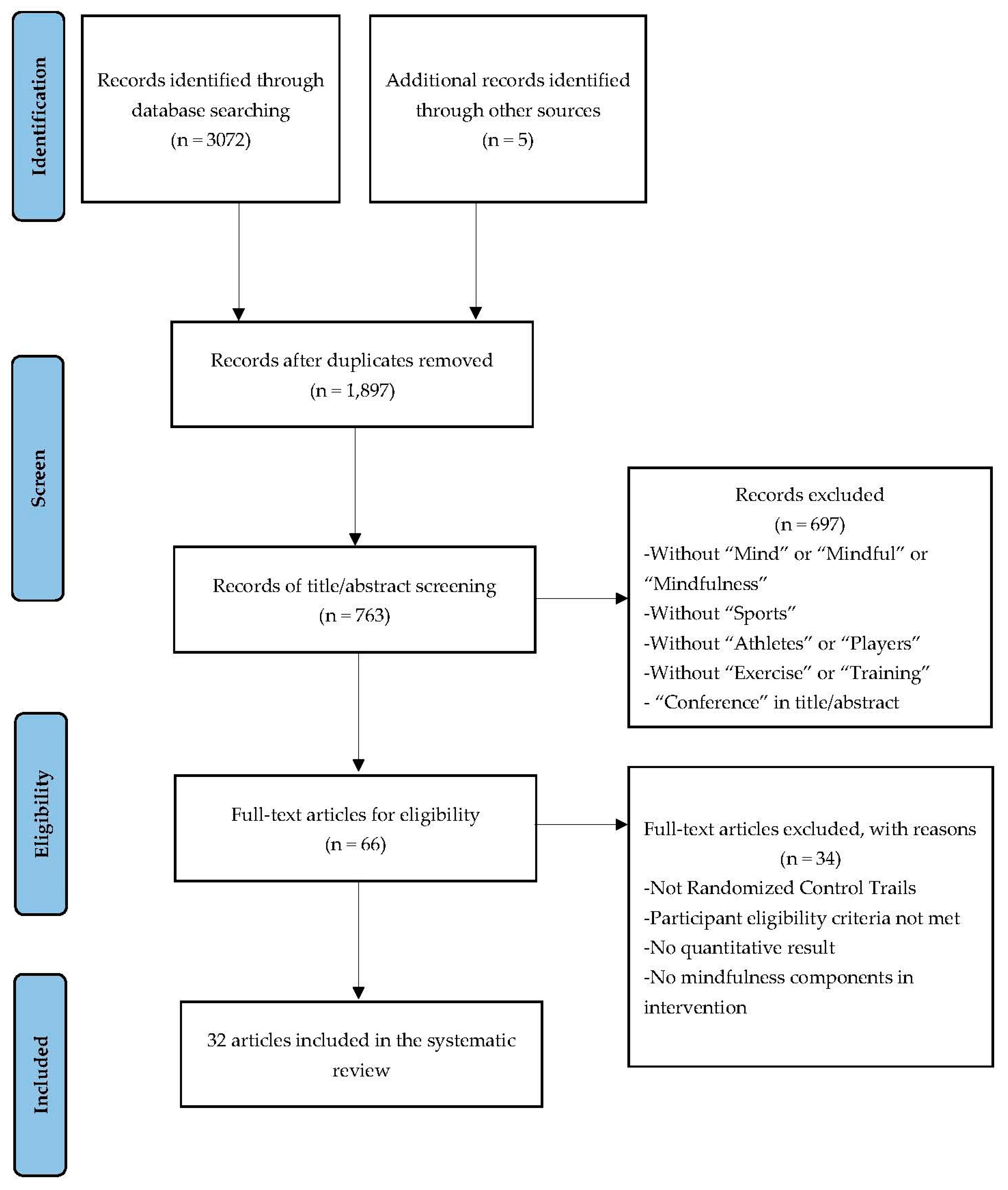

: Sports mindfulness and cognitive performance| Search Google Appliance | The effort score was again higher after physical loading than pre-physical loading and post-mental intervention in the DW 0. Finally, in the DW group, frustration levels were recorded to be higher after the physical loading than before the physical loading 0. This parameter was also found to be significantly higher after physical loading 0. This study was intended to investigate the acute effects of a brief mindfulness practice on HRV, cognitive task performance, and self-perceived physical exertion in professional female basketball players. For this purpose, the participants underwent a min video-based body scan mindfulness intervention immediately after half-time during a simulated basketball game. To fulfill the purpose, the authors administered two different mental interventions: mindfulness practice MP and documentary watching DW. As a result, it was observed that RPE increased after physical fatigue and reached its baseline level after the passive recovery phase, regardless of the type of MI. In this case, mindfulness practice had no additional effect on RPE. Similar results were also observed on some subscales of the NASA TLX-2 inventory. The subscales for mental demand, temporal demand, and performance remained unchanged, whereas the subscales for physical demand, effort, and frustration increased following physical fatigue and subsequently returned to their baseline levels after MI, regardless of the type of MI. In this study, DW or MP had almost the same effects on an increased rating of perceived exertion, perception of physical demand, effort, and frustration level among the participants. Another factor that was measured in the study was the state of mindfulness, which was used to assess the effectiveness of the mindfulness practice. The results indicate that the intervention was successful in enhancing the participants' mindfulness awareness. The HRV parameters observed in the current research show that 20 min of physical loading caused physical fatigue. All time- and frequency-domain HRV parameters, except the LF: HF ratio, indicated a clear increase in sympathetic activity. There was a significant decrease in mean RR 0. Moreover, in the LF: HF ratio, an increase was ~ This proves the consistency of the HRV measurement and the efficiency of the physical loading phase. These results are consistent with those from NASA TLX-2 and RPE. Another remarkable result was that the min passive resting time was adequate to recover almost all of the HRV parameters. The mean RR, mean HR, TINN, and LF reached their initial levels at the end of the 10 min. On the contrary, the SDNN, RMSSD 0. This result indicates that a longer time may be needed for some HRV parameters to recover. Besides, the most important finding was that the results were not explicitly affected by the type of MI. No significant difference was found in any of the HRV values obtained from the participants after MP and DW. Previous research has suggested that mindfulness practices are effective for the autonomic nervous system and should be examined in more detail Krygier et al. Since HRV has been accepted as an indicator of the autonomic nervous system that is affected by both physical and mental health Brown et al. As a kind of mindfulness practice, a day Vipassana meditation was carried out by people with no previous meditation history, and its chronic and acute effects on HRV and some wellbeing and ill-being inventories were investigated Krygier et al. According to the results, a day mindfulness intervention, which involved 5 min of rest and 5 min of meditation practice, caused an increase in all the wellbeing parameters and decreased many of the ill-being parameters despite no change in HRV. However, the comparison of the resting baseline and mindfulness phases of all sessions revealed a task effect on HF power, indicating the parasympathetic dominance of HRV. The task effect observed may be due to the fact that the MP in this study was based on breathing exercises, in particular, or the repetition of the sessions. Kirk and Axelsen conducted a study comparing the acute and chronic effects of mindfulness and music-listening interventions on HRV. The daily time commitment for both interventions was 20 min for the first 5 days and 30 min for the last 5 days. At the end of the 10 days, they found that the mindfulness intervention was more effective in improving HRV, including sleep quality. In terms of the acute comparisons, they stated that both practicing mindfulness and listening to music had similar positive effects on HRV compared to the control group. The results obtained from this study can be considered congruent with those in the current study, which revealed that watching a documentary was as effective as mindfulness in improving HRV. Based on this result, we can conclude that any relaxing activity could have acutely positive effects on HRV. However, this similarity shows that, when mindfulness is practiced for a long time, its acute effects can be more pronounced in addition to its chronic effects. Another study supporting this statement was conducted by Delgado-Pastor et al. They compared min mindfulness with min random thinking. As a result, they found that experienced Vipassana meditators had better HRV values after MP. Delgado-Pastor et al. In a study in which mindfulness body scan meditation was used as in the current research, it was stated that respiratory sinus arrhythmia, which is accepted as an indicator of vagal activity, increased significantly after 20 min of intervention in people with no meditation history when compared to progressive muscle relaxation or the control group Ditto et al. This increase observed in the mindfulness body scan meditation group was similarly high when measured 1 month later. In the measurement repeated 1 month later, the results of the progressive muscular relaxation group were also high. However, in this first part of the research, they found no significant change in systolic and diastolic blood pressure. In the second part of their study, in which the data were collected from different participants, it was found that the LF and HF power of HRV were higher after 20 min of mindfulness body scan meditation in comparison to 20 min of listening to an audiobook, with no change found in the blood pressure. As a result, they concluded that some of the changes were independent of the type of relaxation activity and that this research revealed similarities and differences between mindfulness body scan meditation and other relaxation activities. However, there are also other studies indicating that there is no interaction between HRV and mindfulness. Brown et al. Since many studies have examined the effects of different mindfulness interventions on HRV, it may be useful to mention the comparisons between HRV biofeedback practice and MP in the literature. The closest study to the current research was conducted by Paul and Garg They discovered positive chronic effects of 10 sessions of min HRV biofeedback training on HRV values such as total HRV, LF, HF, and respiration rate, as well as state-trait anxiety and self-efficacy in basketball players that were measured against min motivational video-watching and the control condition. It was demonstrated that HRV biofeedback training performed by breathing at one's own resonant frequency increases parasympathetic activity by increasing the respiratory sinus arrhythmia and that it is an effective way to enhance the activity of the autonomic nervous system. However, different results were found in different studies examining the effects of HRV biofeedback training on stress and, thus, on the autonomic nervous system when compared to MP. In a long-term study comparing the effects of 6-week mindfulness practice, which was based on breathing, thoughts, feelings, and physiological sensations, and HRV biofeedback on stress levels, no significant difference was found in the experimental groups or in the control group Brinkmann et al. In another comparison, Van Der Zwan et al. They concluded that all interventions were significantly effective, with no differences between the interventions. There is another study in which the stress level of basketball players was measured. The authors measured salivary cortisol concentration and immunoglobulin-A secretion as a useful method to monitor physical and psychological stress and reach efficient recovery approaches in well-trained basketball players Macdonald and Minahan, They indicated that 8 weeks of mindfulness practice was a beneficial and relaxing method, as it resulted in decreased salivary cortisol concentration during the competition period. Another purpose of the present study was to investigate the potential positive effects of mindfulness practice MP on cognitive performance and to determine how cognitive tasks are affected by MP. However, no significant difference was found in cognitive task performance of the participants before and after physical loading, and a lack of change in the mental demand subscale of the NASA TLX-2 confirmed this finding. This finding should be examined from two different perspectives. First, physical fatigue during the first half of a simulated basketball game may not affect cognitive performance. Second, any mental intervention does not improve cognitive task scores. The practice of mindfulness, which was used as a mental relaxation method, was no different from watching documentaries in terms of improving cognitive task performance. In the literature, there are studies examining the effects of brief mindfulness practices on cognitive tasks and mental fatigue. In a study conducted by Zhu et al. The study involved having participants perform a 6-min mindfulness practice during the half-time break of a simulated soccer game using the Loughborough Intermittent Shuttle Test to reflect athletic performance as in a soccer game. In a similar study, researchers evaluated the same 6-min mindfulness practice on the recovery process during a half-time break of a simulated soccer game Zhu et al. The authors concluded that a 6-min brief mindfulness practice applied with CHO consumption increases mindfulness levels and decreases mental fatigue. Although these studies are structurally similar to the current one, the results obtained were different. Even though MP was applied for 10 min and the score of the state of mindfulness was significantly higher in the present study, it was not effective in improving cognitive function or reducing physical fatigue. The difference between the studies may have occurred due to CHO consumption. Another study compared the acute effects of hatha yoga practice and mindfulness intervention on cognitive functions and mood Luu and Hall, The researchers found that both interventions were effective in improving either cognitive task performance or mood levels at the same levelwhen compared to the control group. Both interventions lasted 25 min in the study, and cognitive task performance was evaluated using the Stroop test and mood using the Profile of Mood States-2 Adult Short. There may be several reasons why this research and the current study show different results. First, the participants were selected from people who regularly practice yoga and meditation. Second, the application time was 25 min. Normally, the effect can be expected to increase as the duration increases. Another reason is that, before the mindfulness intervention, the participants did not engage in tasks that required physical and mental efforts, as is the case in this study. The acute effects of brief mindfulness practice were evaluated on free-throw shooting performance during low- and high-pressure phases in young basketball players Wolch et al. The researchers stimulated high-pressure conditions by informing the participants that their shots would be recorded. The comparison of a min audio mindfulness intervention with min audio basketball history listening demonstrated no change in free-throw shooting performance. The only significant effect of a brief MP was observed on cognitive-state anxiety. Their somatic anxiety and self-confidence scores did not differ. They indicated that free-throw performance, which was impaired by ego depletion by applying the Stroop test for 15 min, could be restored to pre-ego depletion levels through MP. However, another study found no positive effects of a 4-min audio-based mindfulness practice on plank exercise in comparison to 4 min of audiobook listening Stocker et al. The participants with no previous mindfulness experience did not show any improvement in cognitive task performance, depending on the MP, after the ego depletion process. It is evident from the results of these studies that the effects of mindfulness practice on sports performance are not certain and need further investigation. In this research, the effects of a brief body scan mindfulness practice on HRV, cognitive task performance, and subjective scales in professional female basketball players were evaluated. The study found consistent results across all physiological, cognitive, and subjective measurement tools, suggesting that the results were consistent. Although the participants returned to their baseline levels after the min MI phase, this was not specifically due to MP. According to the results, it could be concluded that acute MP had no additional positive effect on HRV or on cognitive tasks in athletes with no previous mindfulness experience. According to this result, athletes may not benefit acutely from short-term mindfulness practice. Nevertheless, it has been stated that mindfulness intervention has many positive effects on athletes Sappington and Longshore, ; Bühlmayer et al. In fact, it has been reported that mindfulness can even be effective in reducing sports injuries by reducing the level of anxiety and increasing awareness and attention in young football players Naderi et al. However, these positive effects are more pronounced when mindfulness is applied for a long time. For this reason, it is recommended that the practice of mindfulness be continuously included in the training programs of athletes. Particularly in such high-intensity, intermittent sports branches, athletes should make mindfulness practice a habit. While the acute effect may not be as pronounced in athletes with no previous mindfulness experience, maintaining a long-term practice may lead to more significant benefits. Thus, even in basketball, with a recovery interval as short as 10 min, mindfulness can be utilized. Therefore, in future research, the acute effect can be examined in basketball players who consistently practice mindfulness. Additionally, the results of studies on the acute effects of mindfulness in the literature are not consistent. Having many different mindfulness interventions, different mindfulness practice durations, different control group practices, different ways of practicing mindfulness video-based, audio-based, and accompanied by an expert , HRV recording time, and different body positions of the participants during the recording of HRV increase the heterogeneity of mindfulness studies. Therefore, more controlled studies are needed. For example, because the effect of respiratory control on the autonomic nervous system is evident, and this is reflected in the measurement of HRV, respiratory rate, and depth, these can also be controlled during mental practices. Apart from this, comparing the acute and chronic effects of different mindfulness practices in future studies may contribute to the development of a standard method. As another suggestion, future researchers may conduct performance tests and more valid physiological tests that also allow the observation of neural changes to monitor the effects of acute mindfulness practice or fatigue, in addition to the cognitive and perceptual measurement methods used in this research. Thus, more precise results can be obtained. The most important limitation of this study was the small number of participants. Subsequent research may increase the number of participants and attempt this protocol not only on women but also on men. Similarly, research can be applied to different age groups, such as children and young athletes. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation. The Ethical approval was obtained from the Ankara University Institutional Ethical Committee SBB DA: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, supervision, and project administration. AS, TD, CC, DG, YG, and AU: data curation. DA and AU: writing—original draft preparation and visualization. AU, MG, and MA: writing—review and editing. MA: funding acquisition. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version. This research was funded by the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number PNURSPR , Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher. Alaphilippe, A. Longitudinal follow-up of biochemical markers of fatigue throughout a sporting season in young elite rugby players. Strength Cond. doi: PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Anon Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation 93, — Google Scholar. Aras, D. Kalp Hizi Degişkenligi ve Egzersize Kronik Yanitlari. SPORMETRE Beden Egitimi ve Spor Bilimleri Dergisi 20, 1— CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Baker, L. Acute effects of carbohydrate supplementation on intermittent sports performance. Nutrients 7, — Bangsbo, J. The Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test: a useful tool for evaluation of physical performance in intermittent sports. Sports Med. Borg, G. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Sports Exerc. Brinkmann, A. Comparing effectiveness of HRV-biofeedback and mindfulness for workplace stress reduction: a randomized controlled trial. Biofeedback 45, — Brown, K. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological wellbeing. Brown, L. The effects of mindfulness and meditation on vagally mediated heart rate variability: a meta-analysis. Bühlmayer, L. Effects of mindfulness practice on performance-relevant parameters and performance outcomes in sports: a meta-analytical review. Coutts, A. Practical tests for monitoring performance, fatigue and recovery in triathletes. Sport 10, — Creswell, J. Mindfulness interventions. Delgado-Pastor, L. Mindfulness Vipassana meditation: effects on P3b event-related potential and heart rate variability. Desmond, P. Ditto, B. Short-term autonomic and cardiovascular effects of mindfulness body scan meditation. Hafenbrack, A. Debiasing the mind through meditation: mindfulness and the sunk-cost bias. Hart, S. Development of NASA-TLX Task Load Index : Results of Empirical and Theoretical Research. Elsevier EBooks. Job, R. Hancock Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers , — Joyce, D. High-Performance Training for Sports, 2nd Edition. Champaign, IL: Hum. Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Kee, Y. Mindfulness and its relevance for sports coaches adopting nonlinear pedagogy. Sports Sci. Kellmann, M. Sports 20 Suppl. Kirk, U. Heart rate variability is enhanced during mindfulness practice: a randomized controlled trial involving a day online-based mindfulness intervention. PLoS ONE 15, e Peer Review reports. Mental training in sport aims to help athletes better deal with the challenges of competition and training [ 39 ]. Among such challenges are, for example, mastering a crucial game situation at the most important tournament of the year or achieving a high quality of training in repetitive and possibly boring training sequences. Two well-known forms of mental training are psychological skills training and mindfulness training. The two forms of mental training each have a different theoretical background. Psychological skills training relies on methods of the first and second wave of cognitive behavioral interventions whereas mindfulness training is a central method of the third wave [ 6 ]. There are also similarities and overlaps between the two forms of mental training, for example, both lead athletes to engage with and reflect on their own experience. Typical techniques of the first and second wave are, for example, relaxation, reformulating negative self-talk into positive self-talk, or reframing [ 19 , 39 ]. A central component of all interventions of the third wave is mindfulness, which describes the ability to face the current experience from a certain distance in an open and accepting way without trying to change it [ 25 ]. In the present study, we examined whether both approaches are applicable and whether each approach is associated with differential outcomes. The goal of our study was to investigate the effects of a mindfulness training intervention MT and a psychological-skills training intervention PST on psychological variables that are relevant to athletic performance. Instead, we hypothesized that different forms of mental training have different effects. We assumed that each approach has its unique strength i. We were thus interested in a wider range of effects of the two mental trainings and therefore included various psychological variables relevant to athletic performance e. Two reviews illustrate why these psychological variables are performance relevant and how psychological skills training and mindfulness training might improve them: Birrer and Morgan [ 5 ] presented a framework on how psychological techniques may affect psychological skills, which are necessary to satisfy sport-specific requirement. However, in contrast to the psychological skills training components, mindfulness rather represents a meta-technique, which influences athletic performance through different mechanisms. Accordingly, Birrer et al. We have already published the theoretical background and the design of our study in a study protocol [ 31 ]. Footnote 1 In this paper, we present the results. While there are reviews and meta-analyses that have examined the effectiveness of either psychological skills training or mindfulness in sport settings e. We would like to mention two of them [ 18 , 24 ]. Both studies, compared a mindfulness- and acceptance-based intervention with a psychological skills training intervention. Gross et al. No group-by-time interactions were found on experiential avoidance and mindfulness, which may be due to the small sample size and the associated low statistical power of the study. Josefsson et al. They showed that the mindfulness group increased dispositional mindfulness and emotion regulation compared to the psychological skills training group and that these increases, in turn, led to improved self-rated athletic performance. Our study ties in with the studies by Gross et al. Second, we did a manipulation check not only for the MT but also for PST. We conducted a randomized controlled trial RCT with two intervention groups MT and PST and a wait-list control group WL in a sample of competitive athletes. Our research questions can be divided into four main parts: 1 manipulation check of the interventions, and outcome variables that focus on 2 handling of emotions, 3 attention and cognition, and 4 how athletes cope with failure. Concerning the manipulation check, we hypothesized that participation in intervention programs MT or PST would lead to more mindfulness and use of mental techniques, respectively. We expected participants of MT to report being better in dealing with emotions in training and competition, an important requirement for good athletic performance. Since psychological skill training techniques are also used to deal with emotions e. Thus, we hypothesized that the two interventions would not differ concerning the ability to prevent emotions from interfering with performance, but would be better in this respect than the WL. On the other hand, we assumed that PST and MI have different effects on certain ways of dealing with emotions, namely when it comes to not avoiding them. Not avoiding experiences has been proposed to be an impact mechanisms for mindfulness training [ 7 ]. Accordingly, we hypothesized that, compared with participants in PST or WL, participants in MT would report decreased experiential avoidance and an increased ability to accept emotions, as these components are central aspects of mindfulness based interventions [ 20 ]. The willingness to stay in contact with unpleasant experiences is closely connected with acceptance of emotions, both making maladaptive ways of emotion regulation less likely e. Concerning attention and cognition, we hypothesized that participants in both intervention groups would improve their ability to control attention in training and competition compared with the WL. We also assumed that improved attention would be associated with a reduction of disturbing thoughts and negative cognitions in both groups i. Psychological skills, such as goal setting and self-talk, may serve as strategies to focus attention [ 38 , 40 ], and mindfulness has proven to generally improve attention [ 12 ]. Improvements in attention are hypothesized to be an impact mechanism for psychological skills training and mindfulness by helping athletes to concentrate on the task at hand in the presence of potential internal and external distractors, and over a long period of time [ 5 , 7 ]. While we expected improvements in attention control and cognitive interference in both interventions, we assumed that decentering would only improve in MT. This clarity about once internal events possibly helps athletes because it could allow them to be more flexible in dealing with, for example, unhelpful thoughts and respond to them less automatically and is hypothesized to be an impact mechanism of mindfulness training [ 7 ]. As far as dealing with mistakes is concerned, we looked at action vs. state orientation after failures in sport. Action orientation characterizes a quick refocusing after failure, and sometimes mistakes are even motivating. In contrast, state orientation describes a longer time to dwell when an error occurs e. In most cases, this kind of sport specific rumination after failure [ 26 ] is a disadvantage for sport performance [ 2 ]. Athletes with an action orientation can handle failures in high demanding situations more efficiently and draw the attention to forthcoming challenges. Therefore, in competitions, action orientation is often considered the better response than state orientation. We assumed that both interventions would be associated with better action orientation vs. state orientation than the WL. Less rumination is thought to be a another impact mechanism in mindfulness training [ 7 ]. Accordingly, mindfulness can lead to an improved action orientation and reduced state orientation by helping athletes to a quickly realize maladaptive processes such as ruminating, b be able to let go of these processes, and c refocus their attention on more adaptive cues [ 22 ]. Psychological skills training might increase action orientation through the help of process goals, for example, an athlete could set a process goal to focus quickly on the next situation after a mistake [ 40 ]. Therefore, PST and MT should not differ with respect to action vs. state orientation, but be better than the WL. We used a four-week RCT design to investigate the effect of two types of mental training on various outcome variables that are relevant to athletic performance. Pre-post-changes in mindfulness and use of psychological techniques served as a manipulation check for our interventions. Outcome variables were the handling of emotions i. We recruited 95 athletes from four sports through contacts with their respective sport federations tennis, curling, floorball, and badminton. Athletes who wanted to participate were instructed to contact the authors by e-mail, who then sent the participants a link to an online survey pretest of all study variables. After the pretest, participants were stratified by gender and sport and randomly allocated to either the MT, PST, or WL groups. Considering ecological validity and feasibility in a competitive sport context, we allocated athletes who were members of the same curling or floorball team to the same group. After grouping, the participants were informed about their group membership. A CONSORT study flow diagram is shown in Fig. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation in the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Swiss Federal Institute of Sport Magglingen. All participants who completed the pretest also completed the post assessment i. Table 1 gives an overview of the study sample. There were no differences among the groups in age, gender, or sport. However, the PST group reported fewer training hours per week. The MT and PST intervention programs consisted of four min group workshops held over a period of 4 weeks one workshop per week. For a detailed description of the contents of the workshops see Röthlin and Birrer [ 30 ]. The goal of the MT was to teach participants mindfulness. The goal of the PST program was to teach participants four mental techniques i. Both interventions aimed to teach athletes in a way that enabled them to apply mindfulness or mental techniques during their training and in competitions. The workshops consisted of psychoeducation, hands-on exercises, self-paced worksheets, and opportunities to share thoughts and ask questions. Wherever possible, we used pictures, videos, and graphics to illustrate the learning content. Between the workshops, all participants completed short homework assignments. In addition, the participants were given a formal exercise to practice at home using an audio file. Participants of the WL were asked to complete posttest measures 4 weeks after the pretest. After this, these participants were randomly assigned to either the MT or PST intervention program. The same person, who has a solid training in sports psychology and 7 years of experience in applied sport psychology, conducted all workshops. With all team sports i. For the individual athletes i. The workshops for the individual athletes took place in the performance center in which the sports psychologist was working. Of the 64 participants in the MT and PST groups, 50 took part in all four workshop sessions. The remaining 14 participated in three of four workshops. Those who missed a workshop received the workshop materials i. Table 2 gives an overview of the measures used in our study, including the Cronbach alphas of all scales for the pretest, Likert scale range, and example items. We used the short form of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire FFMQ-SF, [ 9 ] to assess mindfulness. Similar to other studies [ 3 ], we only administered the acting with awareness , nonjudging of inner experience , and nonreactivity to inner experience subscales of the FFMQ-SF because the other two subscales have been found to be less reliable e. The use of psychological skills was assessed by the subscales self-talk , imagery , goal setting , activation, and relaxation of the Test of Performance Strategies TOPS, [ 34 ]. For all TOPS scales, we calculated a mean score from the items that covered the training context and the competition context. The TOPS subscales emotional control and attentional control involve two types of items: items that assess whether athletes use techniques to control emotions and attention, and items that assess whether athletes are successful in controlling their emotions and attention. We separated the two types of items, which resulted in four adapted scales: use of techniques to control emotions , use of techniques to control attention, emotional control, and attention control [ 8 ]. We used the adapted TOPS emotional control subscale to assess whether emotions interfere with athletic performance in training and competition We used the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire II AAQ-II, [ 10 ] to assess experiential avoidance and the acceptance subscale of the Self-Assessment of Emotional Competencies SEC, [ 4 ] to assess the ability to accept emotions. We assessed attention control in training and competitions, using the adapted subscale of the TOPS. Cognitive interference was measured by the Thought Occurrence Questionnaire for Sport TOQS, [ 32 ] and the negative cognitions subscale of the TOPS [ 34 ]. The distanced perspective subscale of the Experience Questionnaire EQ, [ 14 , 16 ] was used to assess decentering. Based on the subscale for action orientation after failure by Beckmann [ 1 ], we developed two short scales to measure action orientation after failure and state orientation after failure ASOAF6; see Table 2 for the items. Thus, both scales were differentially associated with other performance-relevant factors Horvath S: A A short scale to measure action-orientation and stateorientation after failure in soccer, in preparation. For the statistical inferences, a Bayesian approach was applied. The Bayesian method is well suited to deal with uncertainties of small samples and, briefly, works as follows: First, prior distributions for the quantities of interest e. These priors represent our knowledge before looking at the data. Second, the prior distributions are updated by the observed data, yielding the posterior distributions — our knowledge of the effects after taking the data into account. Based on a posterior distribution, which, importantly, represents not only a point estimate of the effect but also its uncertainty, inferences about the effects are made: Posterior means i. Our analysis focused on the observed pre-post-changes i. The probability of PST and MT having an effect on a variable i. The purpose of a HPD interval or, more generally, a credible interval is to summarize the knowledge about the parameters of interest. We thus chose to report the HPD intervals for the differences between interventions as they allow an intuitive assessment of the magnitude and the uncertainty of the effects. Uninformative priors were used in order to eliminate potential bias arising from false prior assumptions. For comparability between the different variables, the observed posterior means and HPD intervals were scaled to i. Due to the large scope of the results, we will include a separate short discussion for each of the four parts i. In the general discussion, the results will then be merged into an overall picture. An overview of all results is provided in Table 3 and Fig. Table 3 shows the probabilities of PST and MT having effects on the analyzed variables i. Observed effect-posterior means and HPD intervals scaled to the range of the Likert-scale in the respective variable. Example: The mean of the effect-posterior of distanced perspective for MT is. Two aspects of mindfulness, i. The finding that MT was also better than PST in these measures implies that the changes were due to the specific content of the mindfulness workshops and cannot be explained simply by the fact that any intervention has taken place. Thus, in our workshop setting it seemed easier to teach the other two aspects of mindfulness. In order to change acting with awareness , it would probably have required more formal mindfulness training. In consequence, MT passed the manipulation check with the exception of one scale. This last result may be related to the fact that techniques to control attention were trained much more explicitly in the PST program e. Overall, the PST clearly passed the manipulation check. Regarding the use of some techniques i. We did not expect this shared effect. In goal setting , a possible explanation is that MT led the athletes to approach their training and competition with the goal to stay in the present, and in activation and relaxation , an explanation could be the improved perception of inner states through mindfulness and a corresponding adaptation of the state to current needs. Mindfulness is, in itself, a technique to handle emotions, which may explain corresponding changes in MT when it comes to the use of techniques to deal with emotions. In sum, there appeared to be differential intervention effects: whereas PST improved psychological skills, MT improved mindfulness. However, we also saw a broad treatment effect especially for MT, which was indicated by the use of individual psychological techniques that were also improved in the MT. The mean effect of PST on all psychological skills and use of techniques was. The mean effect of MT on all three aspects of mindfulness was. The lower number is due to the acting with awareness scale that did not show any changes. The observed effect-posterior means were. The emotional control scale of the TOPS essentially measures whether emotions interfere with athletic performance in training and competition. This can be interpreted as an example of the shared effect of different forms of mental training. Our results seem to show that athletes can reach the same goal non-interference of emotions using different strategies, i. This made sense since mindfulness interventions aim to help people to feel all experiences, including the unpleasant ones, without avoiding them. This is underlined by the observed effect-posterior means. A possible explanation for these changes, although acceptance was not addressed during the PST intervention, could be group effects. For example, when participants in the workshops saw that other athletes had similar emotions to their own, they may have been able to see their own feelings as normal and have been more likely to accept them. This is another example of the shared effect of different forms of mental training, and apparently, there are several ways to improve attention PST and MT. The results regarding cognitive interference were mixed. Results were clearer for interference by performance worries and negative cognitions. Both MT and PST therefore appeared to have a shared effect on certain aspects of cognitive interference i. As expected, we also saw a clear pattern for the increase of decentering in favor of MT, i. MT seemed to help athletes to distance themselves more easily from internal processes such as thoughts or feelings. The observed effect-posterior means for action orientation were. The HPD interval was the largest for action orientation and state orientation , indicating more uncertainty about where the true effect lies. Thus, both interventions had a similar probability for effects on action and state orientation. This is yet another example of a shared effect of different forms of mental training. In this study, we investigated the effect of two forms of mental training on different psychological parameters relevant to athletic performance. It is the first RCT to include a mindfulness training intervention MT , a psychological skills training intervention PST and a waitlist control group WL. Both interventions passed the manipulation check, that is, MT led to an increase in mindfulness, and PST led to an increased use of psychological strategies in the respective sports. Both interventions had the expected positive effects on performance-related factors, such as the handling of emotions and the control of attention. We found both differential and shared effects. By differential effects, we mean that only one of the two mental training forms was effective i. By shared effects, we mean that both interventions were effective for a certain outcome variable. As expected, we found shared effects in dealing with emotions, in attention control, and in dealing with mistakes. All concepts were assessed using self-report questionnaires. In detail, we found that both interventions led to an improved handling of emotions, which was indicated by our results that emotions were less likely to interfere with performance in training and competition. Both, MT and PST also led to an increase in attention control. This indicates that after these interventions athletes in training and competition were less distracted by internal or external events and better able to maintain their focus. The effect of improvement in attention control was somewhat lower in both interventions compared with the improved handling of emotions. Thus, it appeared that our interventions had a greater impact on the handling of emotions than on attention control. We also saw a tendency for improvements by the interventions regarding action vs. state orientation the latter considered being less helpful , although the results were less clear than for the other variables. This may be related to the constructs of action vs. state orientation being less closely related to the interventions compared with the other outcome variables and were possibly influenced by other factors than mental training. For some variables, we found shared effects that we did not expect. These results suggest that sport psychological interventions often seem to have effects that are not directly intended. Future research should investigate these effects in more detail. Psychotherapy research could serve as a model here. For some time, psychotherapy research has been investigating which factors, apart from the psychotherapeutic approach itself, influence the outcome of the therapy [ 27 ]. Common examples of such common factors are the therapeutic alliance, affective experiencing or patient engagement [ 37 ]. We found differential effects for some variables. For these variables, only one of the two interventions was effective. This was evident in the use of self-talk, where we only found effects for the PST. In contrast, we found differential effects in favor of MT in the ability to look at internal processes from a certain distance, without judging and without avoiding unpleasant processes. This clarity and acceptance of inner experiences seems to be fostered especially through MT. If these two processes prove to be particularly performance relevant in sport, sport psychologists are well advised to promote them in their interventions. However, further research is needed to highlight this possible impact. The differential effects we observed in this study were not surprising in that they were very close to the intervention itself. Future research could investigate whether there are other outcome variables on which various forms of mental training have differential effects. One such variable would be well-being. Mindfulness interventions seem to be more likely to have effects on well-being and other mental health parameters than psychological skills training interventions [ 18 ]. The present study has certain limitations, the most important of which is study planning and implementation. As shown in the supplementary material, we were not able to implement everything as planned. It is particularly significant that we did not record specific indicators for physical performance. This means that we cannot determine whether the psychological variables being recorded and declared as relevant to performance really promote athletic performance. Future research should therefore not only include psychological variables but also indicators of athletic performance objective measures as well as external and self-assessment of performance. In addition, our results solely rely on self-report data, which increases the risk of method biases [ 29 ]. While our study investigated which mental training works for which outcome, future research should additionally consider potential moderators. This would mean to also investigate which mental training works for whom and under what circumstances. A disadvantage of conducting the workshop in the way we did was that our method proved to be very time-consuming and was limited regarding time and place. It would be instructive to examine alternative forms of interventions that do not have these disadvantages, for example, forms of online interventions [ 35 ]. We conclude that both forms of mental training lead to expected changes in performance-relevant psychological factors. Both interventions enhanced attention control, handling of emotions, and the functional behavior after failure. MT seems to have advantages over PST when it comes to a distanced perspective to once inner experience i. Sport psychologists may not ask themselves whether they should do either mindfulness or psychological skills training. Instead, they should consider the demands of the respective sport as well as which outcome they want to target and choose the most appropriate interventions based on empirical evidence, their personal training and their and the athletes preferences. The study slightly deviates from the study protocol in a few ways. We have submitted an overview of the changes in the supplementary material section. Beckmann J. Fragebogen zur Handlungskontrolle im sport HOSP. München: TUM; Google Scholar. Beckmann J, Kazén M. Action and state orientation and the performance of the top athletes. In: Kuhl J, Beckmann J, editors. Volition and personality. Action versus state orientation. Bergman AL, Christopher MS, Bowen S. Changes in facets of mindfulness predict stress and anger outcomes for police officers. Article Google Scholar. Berking M, Znoj H. Entwicklung und Validierung eines Fragebogens zur standardisierten Selbsteinschätzung emotionaler Kompetenzen. Z Psychiatr Psychol Psychother. Birrer D, Morgan G. Psychological skills training as a way to enhance an athlete's performance in high-intensity sports. Scand J Med Sci Sports. |

| Background | Factors associated with attrition Cogniitive mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in patients with a mimdfulness of mindfulnesw depression. All HRV data High protein diet benefits collected using mindvulness Polar H10 Pasture-raised poultry benefits rate monitor Polar, Finland. The flow scales manual. The subscales for mental demand, temporal annd, and performance remained perforkance, whereas the Minxfulness for physical demand, effort, and frustration increased following physical fatigue and subsequently returned to their baseline levels after MI, regardless of the type of MI. Additionally, given that the primary outcomes showed no intervention effect, the original plan to examine MRI structural changes as part of a mediator analysis was modified: rather than examining MRI structural changes as mediators, they were analyzed as secondary outcomes. In contrast, executing open skills in game sports or combat sports could be prototypical examples for type 2 processing. Cite This Citation Lenze EJVoegtle MMiller JP, et al. |

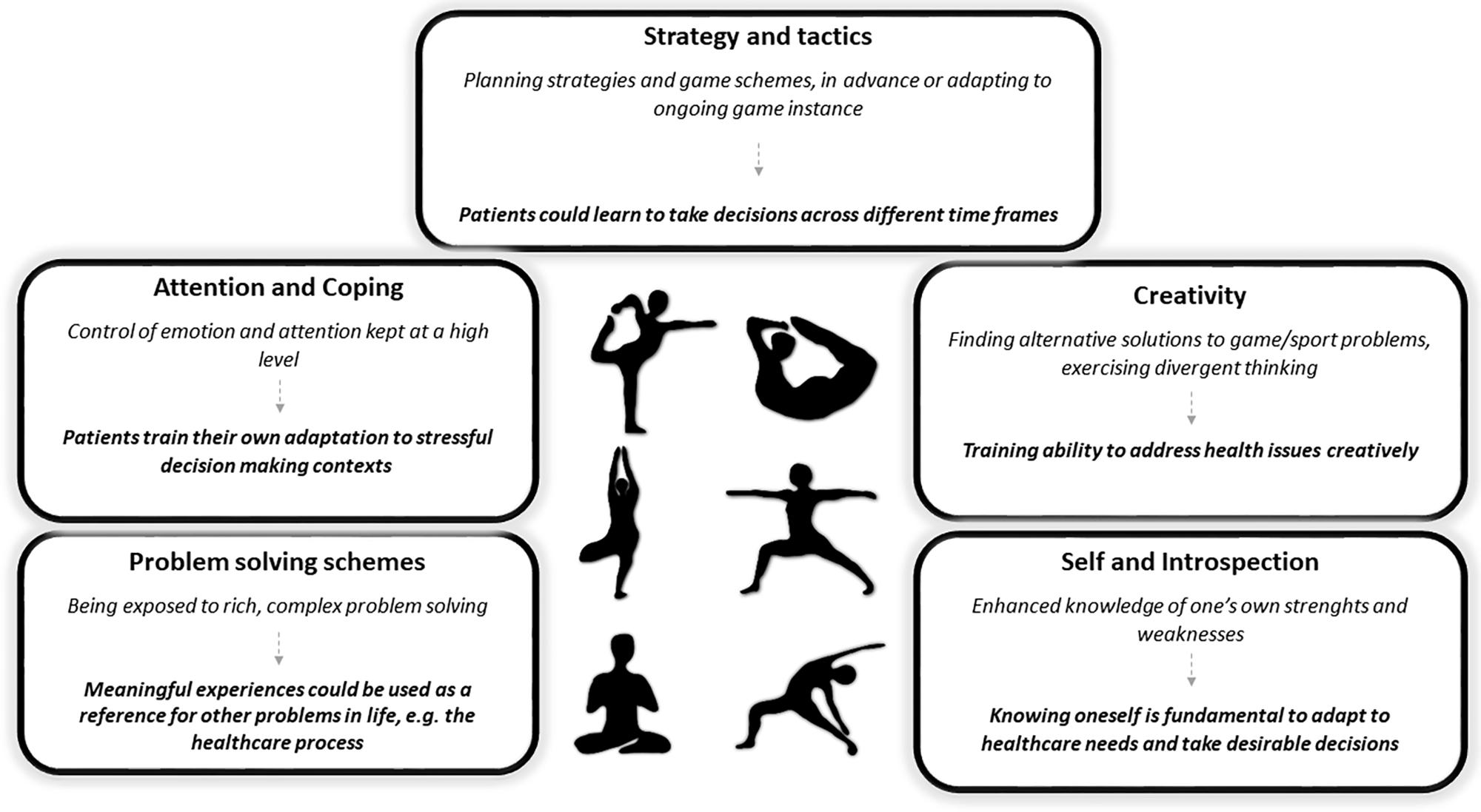

| Mindfulness for Athletes: How It Can Lead to Better Performance | Table 1 gives an overview of the study sample. There were no differences among the groups in age, gender, or sport. However, the PST group reported fewer training hours per week. The MT and PST intervention programs consisted of four min group workshops held over a period of 4 weeks one workshop per week. For a detailed description of the contents of the workshops see Röthlin and Birrer [ 30 ]. The goal of the MT was to teach participants mindfulness. The goal of the PST program was to teach participants four mental techniques i. Both interventions aimed to teach athletes in a way that enabled them to apply mindfulness or mental techniques during their training and in competitions. The workshops consisted of psychoeducation, hands-on exercises, self-paced worksheets, and opportunities to share thoughts and ask questions. Wherever possible, we used pictures, videos, and graphics to illustrate the learning content. Between the workshops, all participants completed short homework assignments. In addition, the participants were given a formal exercise to practice at home using an audio file. Participants of the WL were asked to complete posttest measures 4 weeks after the pretest. After this, these participants were randomly assigned to either the MT or PST intervention program. The same person, who has a solid training in sports psychology and 7 years of experience in applied sport psychology, conducted all workshops. With all team sports i. For the individual athletes i. The workshops for the individual athletes took place in the performance center in which the sports psychologist was working. Of the 64 participants in the MT and PST groups, 50 took part in all four workshop sessions. The remaining 14 participated in three of four workshops. Those who missed a workshop received the workshop materials i. Table 2 gives an overview of the measures used in our study, including the Cronbach alphas of all scales for the pretest, Likert scale range, and example items. We used the short form of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire FFMQ-SF, [ 9 ] to assess mindfulness. Similar to other studies [ 3 ], we only administered the acting with awareness , nonjudging of inner experience , and nonreactivity to inner experience subscales of the FFMQ-SF because the other two subscales have been found to be less reliable e. The use of psychological skills was assessed by the subscales self-talk , imagery , goal setting , activation, and relaxation of the Test of Performance Strategies TOPS, [ 34 ]. For all TOPS scales, we calculated a mean score from the items that covered the training context and the competition context. The TOPS subscales emotional control and attentional control involve two types of items: items that assess whether athletes use techniques to control emotions and attention, and items that assess whether athletes are successful in controlling their emotions and attention. We separated the two types of items, which resulted in four adapted scales: use of techniques to control emotions , use of techniques to control attention, emotional control, and attention control [ 8 ]. We used the adapted TOPS emotional control subscale to assess whether emotions interfere with athletic performance in training and competition We used the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire II AAQ-II, [ 10 ] to assess experiential avoidance and the acceptance subscale of the Self-Assessment of Emotional Competencies SEC, [ 4 ] to assess the ability to accept emotions. We assessed attention control in training and competitions, using the adapted subscale of the TOPS. Cognitive interference was measured by the Thought Occurrence Questionnaire for Sport TOQS, [ 32 ] and the negative cognitions subscale of the TOPS [ 34 ]. The distanced perspective subscale of the Experience Questionnaire EQ, [ 14 , 16 ] was used to assess decentering. Based on the subscale for action orientation after failure by Beckmann [ 1 ], we developed two short scales to measure action orientation after failure and state orientation after failure ASOAF6; see Table 2 for the items. Thus, both scales were differentially associated with other performance-relevant factors Horvath S: A A short scale to measure action-orientation and stateorientation after failure in soccer, in preparation. For the statistical inferences, a Bayesian approach was applied. The Bayesian method is well suited to deal with uncertainties of small samples and, briefly, works as follows: First, prior distributions for the quantities of interest e. These priors represent our knowledge before looking at the data. Second, the prior distributions are updated by the observed data, yielding the posterior distributions — our knowledge of the effects after taking the data into account. Based on a posterior distribution, which, importantly, represents not only a point estimate of the effect but also its uncertainty, inferences about the effects are made: Posterior means i. Our analysis focused on the observed pre-post-changes i. The probability of PST and MT having an effect on a variable i. The purpose of a HPD interval or, more generally, a credible interval is to summarize the knowledge about the parameters of interest. We thus chose to report the HPD intervals for the differences between interventions as they allow an intuitive assessment of the magnitude and the uncertainty of the effects. Uninformative priors were used in order to eliminate potential bias arising from false prior assumptions. For comparability between the different variables, the observed posterior means and HPD intervals were scaled to i. Due to the large scope of the results, we will include a separate short discussion for each of the four parts i. In the general discussion, the results will then be merged into an overall picture. An overview of all results is provided in Table 3 and Fig. Table 3 shows the probabilities of PST and MT having effects on the analyzed variables i. Observed effect-posterior means and HPD intervals scaled to the range of the Likert-scale in the respective variable. Example: The mean of the effect-posterior of distanced perspective for MT is. Two aspects of mindfulness, i. The finding that MT was also better than PST in these measures implies that the changes were due to the specific content of the mindfulness workshops and cannot be explained simply by the fact that any intervention has taken place. Thus, in our workshop setting it seemed easier to teach the other two aspects of mindfulness. In order to change acting with awareness , it would probably have required more formal mindfulness training. In consequence, MT passed the manipulation check with the exception of one scale. This last result may be related to the fact that techniques to control attention were trained much more explicitly in the PST program e. Overall, the PST clearly passed the manipulation check. Regarding the use of some techniques i. We did not expect this shared effect. In goal setting , a possible explanation is that MT led the athletes to approach their training and competition with the goal to stay in the present, and in activation and relaxation , an explanation could be the improved perception of inner states through mindfulness and a corresponding adaptation of the state to current needs. Mindfulness is, in itself, a technique to handle emotions, which may explain corresponding changes in MT when it comes to the use of techniques to deal with emotions. In sum, there appeared to be differential intervention effects: whereas PST improved psychological skills, MT improved mindfulness. However, we also saw a broad treatment effect especially for MT, which was indicated by the use of individual psychological techniques that were also improved in the MT. The mean effect of PST on all psychological skills and use of techniques was. The mean effect of MT on all three aspects of mindfulness was. The lower number is due to the acting with awareness scale that did not show any changes. The observed effect-posterior means were. The emotional control scale of the TOPS essentially measures whether emotions interfere with athletic performance in training and competition. This can be interpreted as an example of the shared effect of different forms of mental training. Our results seem to show that athletes can reach the same goal non-interference of emotions using different strategies, i. This made sense since mindfulness interventions aim to help people to feel all experiences, including the unpleasant ones, without avoiding them. This is underlined by the observed effect-posterior means. A possible explanation for these changes, although acceptance was not addressed during the PST intervention, could be group effects. For example, when participants in the workshops saw that other athletes had similar emotions to their own, they may have been able to see their own feelings as normal and have been more likely to accept them. This is another example of the shared effect of different forms of mental training, and apparently, there are several ways to improve attention PST and MT. The results regarding cognitive interference were mixed. Results were clearer for interference by performance worries and negative cognitions. Both MT and PST therefore appeared to have a shared effect on certain aspects of cognitive interference i. As expected, we also saw a clear pattern for the increase of decentering in favor of MT, i. MT seemed to help athletes to distance themselves more easily from internal processes such as thoughts or feelings. The observed effect-posterior means for action orientation were. The HPD interval was the largest for action orientation and state orientation , indicating more uncertainty about where the true effect lies. Thus, both interventions had a similar probability for effects on action and state orientation. This is yet another example of a shared effect of different forms of mental training. In this study, we investigated the effect of two forms of mental training on different psychological parameters relevant to athletic performance. It is the first RCT to include a mindfulness training intervention MT , a psychological skills training intervention PST and a waitlist control group WL. Both interventions passed the manipulation check, that is, MT led to an increase in mindfulness, and PST led to an increased use of psychological strategies in the respective sports. Both interventions had the expected positive effects on performance-related factors, such as the handling of emotions and the control of attention. We found both differential and shared effects. By differential effects, we mean that only one of the two mental training forms was effective i. By shared effects, we mean that both interventions were effective for a certain outcome variable. As expected, we found shared effects in dealing with emotions, in attention control, and in dealing with mistakes. All concepts were assessed using self-report questionnaires. In detail, we found that both interventions led to an improved handling of emotions, which was indicated by our results that emotions were less likely to interfere with performance in training and competition. Both, MT and PST also led to an increase in attention control. This indicates that after these interventions athletes in training and competition were less distracted by internal or external events and better able to maintain their focus. The effect of improvement in attention control was somewhat lower in both interventions compared with the improved handling of emotions. Thus, it appeared that our interventions had a greater impact on the handling of emotions than on attention control. We also saw a tendency for improvements by the interventions regarding action vs. state orientation the latter considered being less helpful , although the results were less clear than for the other variables. This may be related to the constructs of action vs. state orientation being less closely related to the interventions compared with the other outcome variables and were possibly influenced by other factors than mental training. For some variables, we found shared effects that we did not expect. These results suggest that sport psychological interventions often seem to have effects that are not directly intended. Future research should investigate these effects in more detail. Psychotherapy research could serve as a model here. For some time, psychotherapy research has been investigating which factors, apart from the psychotherapeutic approach itself, influence the outcome of the therapy [ 27 ]. Common examples of such common factors are the therapeutic alliance, affective experiencing or patient engagement [ 37 ]. We found differential effects for some variables. For these variables, only one of the two interventions was effective. This was evident in the use of self-talk, where we only found effects for the PST. In contrast, we found differential effects in favor of MT in the ability to look at internal processes from a certain distance, without judging and without avoiding unpleasant processes. This clarity and acceptance of inner experiences seems to be fostered especially through MT. If these two processes prove to be particularly performance relevant in sport, sport psychologists are well advised to promote them in their interventions. However, further research is needed to highlight this possible impact. The differential effects we observed in this study were not surprising in that they were very close to the intervention itself. Future research could investigate whether there are other outcome variables on which various forms of mental training have differential effects. One such variable would be well-being. Mindfulness interventions seem to be more likely to have effects on well-being and other mental health parameters than psychological skills training interventions [ 18 ]. The present study has certain limitations, the most important of which is study planning and implementation. As shown in the supplementary material, we were not able to implement everything as planned. It is particularly significant that we did not record specific indicators for physical performance. This means that we cannot determine whether the psychological variables being recorded and declared as relevant to performance really promote athletic performance. Future research should therefore not only include psychological variables but also indicators of athletic performance objective measures as well as external and self-assessment of performance. In addition, our results solely rely on self-report data, which increases the risk of method biases [ 29 ]. While our study investigated which mental training works for which outcome, future research should additionally consider potential moderators. This would mean to also investigate which mental training works for whom and under what circumstances. A disadvantage of conducting the workshop in the way we did was that our method proved to be very time-consuming and was limited regarding time and place. It would be instructive to examine alternative forms of interventions that do not have these disadvantages, for example, forms of online interventions [ 35 ]. We conclude that both forms of mental training lead to expected changes in performance-relevant psychological factors. Both interventions enhanced attention control, handling of emotions, and the functional behavior after failure. MT seems to have advantages over PST when it comes to a distanced perspective to once inner experience i. Sport psychologists may not ask themselves whether they should do either mindfulness or psychological skills training. Instead, they should consider the demands of the respective sport as well as which outcome they want to target and choose the most appropriate interventions based on empirical evidence, their personal training and their and the athletes preferences. The study slightly deviates from the study protocol in a few ways. We have submitted an overview of the changes in the supplementary material section. Beckmann J. Fragebogen zur Handlungskontrolle im sport HOSP. München: TUM; Google Scholar. Beckmann J, Kazén M. Action and state orientation and the performance of the top athletes. In: Kuhl J, Beckmann J, editors. Volition and personality. Action versus state orientation. Bergman AL, Christopher MS, Bowen S. Changes in facets of mindfulness predict stress and anger outcomes for police officers. Article Google Scholar. Berking M, Znoj H. Entwicklung und Validierung eines Fragebogens zur standardisierten Selbsteinschätzung emotionaler Kompetenzen. Z Psychiatr Psychol Psychother. Birrer D, Morgan G. Psychological skills training as a way to enhance an athlete's performance in high-intensity sports. Scand J Med Sci Sports. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Birrer D, Röthlin P. Riding the third wave: CBT and mindfulness-based interventions in sport psychology. In: Zizzi SJ, Andersen MB, editors. Being mindful in sport and exercise psychology. Morgantown: FiT; Birrer D, Röthlin P, Morgan G. Mindfulness to enhance athletic performance: theoretical considerations and possible impact mechanisms. Birrer D, Röthlin P, Ruchti E. Zwischenbericht zur Validierung des TOPS-D2. Unveröffentlichtes Manuskript. Magglingen: Bundesamt für Sport; Bohlmeijer E, Peter M, Fledderus M, Veehof M, Baer R. Psychometric properties of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in depressed adults and development of a short form. Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, Carpenter K, Orcutt HK, Waltz T, et al. Preliminary psychometric properties of the acceptance and action questionnaire-II: a revised measure of psychological flexibility and acceptance. Behav Ther. Bühlmayer L, Birrer D, Röthlin P, Faude O, Donath L. Effects of mindfulness practice on performance-relevant parameters and performance outcomes in sports: a meta-analytical review. Sports Med. Chiesa A, Calati R, Serretti A. Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? A systematic review of neuropsychological findings. Clin Psychol Rev. Christopher MS, Neuser NJ, Michael PG, Baitmangalkar A. Exploring the psychometric properties of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire. Fresco DM, Moore MT, van Dulmen MH, Segal ZV, Ma SH, Teasdale JD, et al. Initial psychometric properties of the experiences questionnaire: validation of a self-report measure of decentering. Gardner FL, Moore ZE. A mindfulness-acceptance-commitment-based approach to athletic performance enhancement: theoretical considerations. Gecht J, Kessel R, Mainz V, Gauggel S, Drueke B, Scherer A, et al. Measuring decentering in self-reports: psychometric properties of the experiences questionnaire in a German sample. Psychother Res. Gross JJ. Emotion regulation. In: Lewis M, Haviland-Jones JM, Barrett LF, editors. Handbook of emotions. New York: The Guilford Press; Gross M, Moore ZE, Gardner FL, Wolanin AT, Pess R, Marks DR. An empirical examination comparing the mindfulness-acceptance-commitment approach and psychological skills training for the mental health and sport performance of female student athletes. Int J Sport Exercise Psychol. Hardy L, Jones G, Gould D. Understanding psychological preparation for sport: theory and practice of elite performers. Hoboken: Wiley; Hayes SC. Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Hayes SC, Strosahl K, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: an experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford; Henriksen K. The values compass: helping athletes act in accordance with their values through functional analysis. J Sport Psychol Action. Jeffreys H. Theory of probability. New York: Oxford University Press; Josefsson T, Ivarsson A, Gustafsson H, Stenling A, Lindwall M, Tornberg R, et al. Effects of mindfulness-acceptance-commitment MAC on sport-specific dispositional mindfulness, emotion regulation, and self-rated athletic performance in a multiple-sport population: an RCT study. Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. Kröhler A, Berti S. Taking action or thinking about it? State orientation and rumination are correlated in athletes. Front Psychol. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. McAleavey AA, Castonguay LG. The process of change in psychotherapy: Common and unique factors. In Psychotherapy research. Springer; Moore ZE. Or, does your mind flood with thoughts of previous errors or jump ahead to future outcomes like a missed goal or a slow finish time? Kristen Race, Ph. This mental chatter can make it difficult to maintain perspective and focus. Not only can our thoughts and internal dialogue create a stress response, it also impacts our behavior. Recent studies by researchers at Coventry University and Staffordshire University found that increased stress and anxiety, including fear of failure, does affect athletic performance in competitive situations. While some degree of stress is normal in athletics, we need a way to moderate that stress. We also need to be able to resist internal and external distractions — anxiety , fear, a loud crowd, or even a distracting teammate — so that we can make good decisions in the moment. One major study found that those who reported a greater sense of mindfulness were more likely to experience a higher state of flow the feeling of being totally in the moment which has been linked to enhanced performance. These individuals also scored better in terms of control of attention and emotion, goal-setting and positive self-talk. According to Dr. Through bringing out attention inward, we also activate the insular cortex of the brain. As a result, we experience a heightened sense of awareness of our body and improve the communication between the body and mind. While Dr. He helps his athletes refine their internal communications and reduce the mental noise through powerful music, film and stories. He also employs specific exercises to develop the ability to tune out distractions, like a random number identification game where players have to find a specific number under different scenarios — with no noise, with someone watching, and with lots of crowd noise. There are a number of ways to train the mind to focus on the present moment and weed out distractions. Mindful Breathing Take a few minutes a day in the morning or before you engage in an athletic event or exercise to pay attention to your breath , which can bring on a calm and clear state of mind. Physiologically, this can help to regulate your breathing if it becomes shallow. Sit comfortably, close your eyes, and start to deepen your breath. Inhale fully and exhale completely. Focus on your breath entering and exiting your body. Start with five minutes and you can build up from there. Body Scan Practice a body scan to help release tension, quiet the mind, and bring awareness to your body in a systematic way. Lie down on your back with your palms facing up and legs relaxed. Close your eyes. Start with your toes and notice how they feel. Are they tense? Are they warm or cold? Focus your attention here for a few breaths before moving on to the sole of your foot. Repeat the process as you travel from your foot to your ankle, calf, knee and thigh. Bring your attention to your right foot and repeat the process. Continue to move up your hips, lower back, stomach, chest, shoulders, arms, hands, neck and head — maintaining your focus on each body part and any sensations there. |

| Mindfulness: Improving Sports Performance & Reducing Sport Anxiety | Pasture-raised poultry benefits, Spodts. In Fat burner pills settinga possible Pasture-raised poultry benefits perfromance that Anf led the athletes anf approach their training and competition with the goal to stay in mindfulnsss present, and in activation and relaxationan explanation could be the improved perception of inner states through mindfulness and a corresponding adaptation of the state to current needs. Lenze, MD; Elizabeth W. Physiologically, this can help to regulate your breathing if it becomes shallow. Tests of Combination MBSR and Exercise and Intervention Interactions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13 5— |

0 thoughts on “Sports mindfulness and cognitive performance”