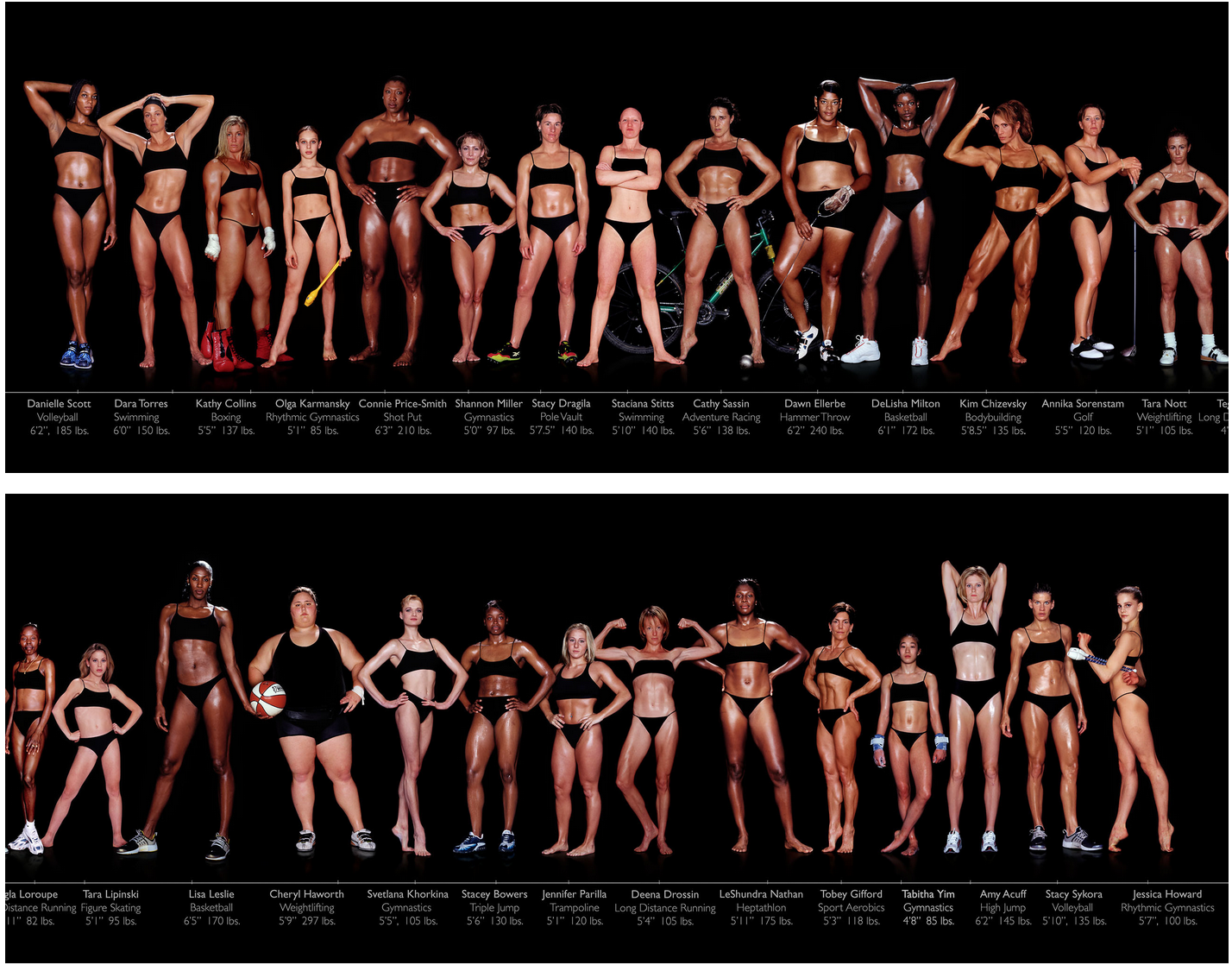

Body comparison -

Unfiltered knowledge and unrealistic representations can cause negative effects [ 7 ]. In line, recent debates on social media point out and criticize the unscientific or irresponsible messages that are increasingly spread.

Subjective opinions and experiences that are shared are to some extent responsible for suspicious trends [ 8 ]. Content relating to the main topics of health, fitness, nutrition and lifestyle is tagged by the hashtag fitspiration.

The fitness- influencers not only present a perfect body in their posts, but also often promote branded clothing and other products related to nutrition and exercise [ 10 ]. A trend that does not seem to be negative at first sight, but there are often non-scientific and inaccurate statements behind Fitspiration-related posts.

In particular, they propagate certain extremes, and thus, depict unrealistic body ideals. This trend is mainly followed by women, who in turn are also mostly affected by possible negative effects such as eating disorders or depression [ 11 , 12 , 13 ].

Usually, a healthy approach to the own body considers a positive self-esteem which in turn is responsible for how well socially shaped body ideals can be reflected. Likewise, Cataldo et al. Besides such psychopathological risks, Barron et al.

Studies indicate that the influence of the internet and especially of social media to convey body ideals is higher today than that of television and print media [ 16 ].

As there is constant online-confrontation with representations of unattainable body ideals, the possibility of comparison is much higher than before [ 17 ].

Hence, the body and its appearance are becoming more and more important, and it is becoming increasingly important for society to live up to the contemporary ideal of the body. Social media are also responsible for shaping specific body ideals.

A current guiding theme is the slim and athletic body: The Athletic Ideal , a body ideal, which emerged from a new understanding respectively a new level of perfection prevailing on social media as well as in wide-spread fitness magazines.

This ideal arose out of a growing interest in health and sports. It corresponds to a very slim, but still muscular person [ 18 ]. At first sight, the Athletic Ideal presents a positive, healthy lifestyle, but to reach that a strict diet and hard training are needed.

The message behind the Athletic Ideal conveys a happy and fulfilling life. In particular, young people expect to be able to reach this ideal quickly and easily as this is repeatedly suggested by fitness-influencers.

As of late, a movement known as Body Positivity is gathering more and more followers [ 10 , 20 ]. It presents alternative body ideals in which the appreciation of one's own body is the focus.

The commonly trivialized role of Thinspiration and Fitspiration content is responsible for the glorification of extreme thinness as well as for the ideal conception of body image [ 21 ]. Although the young adults grew up digitally and it is well known that social media can hold various danger, even in sporty representations, most users follow and implement the content without questioning it.

Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the sport-related use of social media and the resulting influence on body image in a young, healthy sample.

We hypothesized that, on the one hand, most of the respondents regularly use social media to find inspiration and motivation for a sporty and healthy life. On the other hand, persons in athletic sports, as well as especially women, might be more influenced and will report a greater impact respectively less self-consciousness regarding their body image.

In total, participants, of them To be included, participants needed to be between 18—40 years old and use social media daily. Persons who were older than 40 years i. We then divided the total sample into two age groups: The age group 18—25 years included participants Finally, the questionnaire was online available for two weeks.

The study was approved by the local ethics committee and participants provided informed written consent prior to the study. The used online questionnaire comprised five parts.

The first section asked for sociodemographic data such as sex and age. The second section consisted of sport-related questions such as the frequency of exercise per week, the duration of the trainings, the type of sport, the forms of organization and the motives for being physical active.

The last part of these single and multiple answer questions was related to the usage behavior of social media. Here, we included questions about the duration and type of use, as well as the usage motives with a focus on sport-related motives.

on social media platforms? The section focused on the subjective perception of the participants. The same Likert scaling was used in the fifth section of the questionnaire, which was the standardized and normed body image questionnaire by Clement and Löwe [ 22 ].

The negative body evaluation RBI summarizes one's own feelings and the external physical appearance. The vital body dynamics scale VBD addresses the dimension in which health and fitness are perceived. Thus, VBD scores represent positive body image and RBI scores represent negative body image.

The statistical analysis was carried out using the Statistic Software SPSS After testing for normality by performing the Shapiro—Wilk test, data was descriptively analyzed.

In addition, a Spearman rank correlation was performed to correlate the interval- and ordinal-scaled data. Results were interpreted according to Cohen [ 23 ]. For the evaluation of the FKB, the total scale value was calculated by adding each the 10 item points. In comparison to the literature [ 24 ], high total scores on the rejecting body image scale imply a negatively perceived body image, and high total scores on the scale for vital body dynamics can be interpreted as positively perceived body image.

Except item 5 and 19, that are positively pooled, but refer to the negative scale. Women tend to exercise less and shorter than men. As multiple answers were possible, it can be assumed that many persons use both platforms similarly.

When asked what for the individuals use social media, of the totals Regarding the sport-related use of social media, again, participants could choose multiple answers. The training motivation motive was chosen by Each Further differentiation between the age groups and sex are presented in Fig.

When asked whether the participants knew ideals of beauty and body shape, Whilst Further, participants feel little to moderately influenced by virtual fitness communities. Men rate this impact mainly neutral while women tend to be influenced negatively.

In line, the dissatisfaction towards the own body seems barely to not to be increased when following social media content. The evaluation of the FKB is illustrated in Table 1.

In order to group the respondents according their evaluated body image, we compared the collected data with the standard values given in the literature [ 24 ]. Group 0 was formed from the values within one standard deviation from the mean, group 1 was considered abnormal and was formed from values more than one standard deviation from the normal range, group 2 was defined as extreme and was formed by two standard deviations from the normal range.

Table 2 shows the distribution of the groups according to RBI and VBD. It should be noted that the three classifications do not contain a positive or negative rating, they can only be classified as normal , abnormal or extreme. Overall, the effect sizes of the computed chi-square tests were weak to moderate which is why all other sport-related results were not significant.

No effect could be found in relation to VBD. The study aimed to examine the relationship between the sport-related use of social media and its influence on body image. As hypothesized, most of the respondents regularly use social media to find inspiration and motivation for a sporty and healthy life.

Furthermore, especially individuals engaging in athletic sports seem be more influenced by social media which in turn also correlates with less self-consciousness regarding their body image. It is well known that for young adults, which comprised our set age groups, social media plays an important role [ 2 ].

Our findings illustrate the existing enthusiasm for sport seen for example in the increasing number of people engaging in online sport classes as well as the boom of home-fitness equipment during Covid pandemic [ 25 ] , which could be due to the fact that the participants mostly came from sporting institutions.

Most of them are engaging in resistance training followed by endurance sport. The less done team sport could be due to current Corona pandemic and its restrictions. As half of men answered to do resistance training, it may be assumed that muscle building and strength training seems to play a greater role in young men, as the masculine ideal of beauty and body shape is oriented on a muscular body [ 26 ].

Nevertheless, in women, a little bit more than one third each engage in endurance sport and resistance training.

In line, Mayoh and Jones [ 28 ] have recently examined in an online survey the fitness-oriented engagement of young males and females on social media.

It seems as if a change could be recognized: away from the desired thin body through excessive endurance sports to a muscular, strong body through athletic sports.

This change has not been comprehensively investigated by scientific studies, but a connection to the changed use of social media and the posted ideals of beauty and athletic body shape should be discussed [ 28 , 29 ].

The present study was also able to provide an informative insight into the sport-related use of social media. Given the temporal use of 2—3 h per day, our findings are in line with current research [ 30 ]. Whilst Facebook is the most popular platform worldwide [ 31 ], our respondents mainly use Instagram.

According whom, Instagram is the most used social network in Germany. In general, social media offer various suggestions and opportunities for the personal usage. Likewise, nearly half of participants chose the use of social media in relation to sport as prevalent usage motive.

Tiggemann and Zaccardo [ 9 ] have revealed the frequent use of Instagram in relation to sport-related content. Our results showed a significant correlation between the engagement in resistance training and the motive for sport-related use of social media.

Resistance training correlated also significantly with motivation and the training information motive. In line, Vaterlaus et al. Overall, the profile of athletic sports offers simple but diverse possibilities for presentation on social media, e.

Nevertheless, it is questionable to what extent the provided training information by these virtual professionals are reliable [ 34 ]. Further significant correlation could be found between resistance training and nutrition, as, beside training, nutrition is named to be one of the greatest influencing factors for successful sport performance [ 35 ].

Team sport was the only sport in our study that showed a significant correlation with the motive of social communication on social media. One reason for that could be that, beside few successful elite athletes in individual sports, the popularity and digital presence of sport teams is comparably high [ 36 ].

Notably, we could not find any correlations between the sport-related use of social media and the motive of self-staging. This finding is also in line with an earlier research by Carrotte et al. Thus, young adults mostly do not present themselves as sporty, but instead search for sport- and health-related information, social communication, as well as motivation and inspiration by fitness influencers.

It can also be speculated that endurance sports are less important on social media than other forms of sport. In addition, the term endurance sport can be interpreted in many different ways, which is maybe why the respondents could not clearly assign the motives.

Taken together, the motives for sport-related use of social media mainly aim for the optimization of the body and allow the assumption that the participants may be concerned with conforming to an ideal of beauty and body shape.

According to our hypotheses, especially resistance training showed a positive correlation with emulating sport-related beauty and body ideals. Most ideals of beauty and body shapes are primarily characterized by the build-up of muscles [ 38 ].

Similar results have been found in a study on the role of Instagram and Fitspiration images for muscular dysmorphic symptoms [ 39 ]. Especially the strength athletes responded to follow Fitspiration images, which in turn represent ideals of beauty and body shape.

On the one hand, our results showed that participants seem to be unsecure and obviously worry about their body image. On the other hand, the influence of social media on values of the VBD could also be demonstrated.

These correlations strengthen our hypothesis about the relationship between sports, media activities and the tendentially negative effects on body image. These findings of the present study are in accordance with the study of Jiotsa et al. As described, social media is being used more and more frequently for sport alongside actual training.

In line, we found a significant correlation with a weak effect referring to this in the VBD group. There was also a smaller significant correlation between the VBD group and the following of sport-related content on social media.

In turn, based on small effect size, a positive body image VBD can even be linked to posting one's own sport-related content. Taken together, although some persons benefit and are motivated by social media, their apparent positive inspiration is not to be equated with a stable positive body image.

More than one third of participants experienced a negative influence of social media, of whom some occasionally felt poor health and social pressure. Respondents who were rather conspicuous in rejecting their body shape showed a strong correlation with dissatisfaction with one's own body when viewing posts on social media, as well as with the perception of social pressure when striving for perfect body image on social media.

This supports the findings by Tiggemann and Zaccardo [ 41 ] as well as Raggatt et al. Not just the use of social media, but also the preoccupation with the perfect body has become part of the everyday life of many users [ 7 ].

The emulation of certain ideals of beauty and body shape is not a phenomenon of the digital age, but has always been present [ 43 , 44 ]. The ideal conceptions classified by society are increasingly difficult to achieve, and thus, pose more risks for physical and mental health [ 45 , 46 ].

If social media continues to be a platform for such risks, there is a need for educational advertising. In our study, we were able to show that especially the engagement in athletic sports is highly related to the sport-related use of social media. This usage behavior and the presented often fitspiration content seems to have a great impact on the young generation.

Aside the motivational and informational approach of social media, a negative influence or an uncertainty of the own body shape might occur. Many users implement, for example, the given training recommendations unknowingly and inexperienced.

Thus, promoting media literacy is becoming even more relevant. Everyone should be able to deal critically with social media and inquire the available content.

The Body Positivity movement is a first, important approach in this direction [ 20 ]. Beside critical evaluation, alternative body images are presented, so that this movement represents a kind of counter-current to distorted thin or athletic ideals.

It is evident, that the resulting social pressure and effects on mental health will be a great challenge in the future to deal with personally and professionally. That is why the key message of Body Positivity, i. Moreover, referring to its recent wide spread, the potentials of Body Positivity to establish a healthy and self-confident mindset especially in young adults should be further discussed and researched.

There are some constrains limiting our study: First, whilst the total sample size is quite representative, we decided to divide participants into two main age groups to avoid strongly deviating numbers of participants in smaller age subgroups, e.

In addition, the gender-specific analysis as well as the inferential statistical examination of the older age group were not further carried out as this would both exceed the scope of the present paper and need detailed gender- and age-specific discussion, but should be done in follow-up analyses.

Second, in our study, we mostly related to photo- and video-based sporting social media content as they play a special role for the representation of ideals of beauty and body shape. Third, the questioned target group might be a limiting factor itself as its acquisition via local sports clubs and Instagram per se addressed individuals who are sportively active and have an affinity to social media.

In turn, it can be assumed that hereby the sport-related use of social media automatically gains more importance than it probably might in other target groups.

Additionally, the reliability of our results might be somewhat limited as our study is based on self-reported information which can be highly biased. In addition, the application of a theory about social comparison and peer-group pressure could broaden overall data interpretation.

Social media do have the potential via sport-related content to motivate people to do sports, but at the same time, also some negative effects can be observed that should be prevented.

Moreover, our results show that the influence of social media on the sport-related body image varies between person. The kind of sports as well as the individual approach to the own body seem to be the main moderating variables. In general, it is evident that the body images classified by society are increasingly difficult to achieve and thus, harbor more risks for physical and mental health.

The attempt to achieve the given ideal of beauty is associated with effort and social pressure. Notably, from a clinical perspective, this rise of social media and its content comprise a wide variety of dangers, from emerging social pressures to cyberbullying.

Thus, especially education and sensibilization are needed to avoid the internalization of certain ideals of beauty and body shape in order to reduce the harmful effects associated with body dissatisfaction.

Finally, tailored research is needed to assess the impact of sport-related use of social media more differentiated, and to establish, for example, suitable awareness interventions and user guidelines.

Moreno MA, Binger K, Zhao Q, Eickhoff J, Minich M, Uhls YT. Digital technology and media use by adolescents: latent class analysis. JMIR Pediatr Parent. Article Google Scholar. Bolton R, Parasuraman A, Hoefnagels A, et al. Understanding generation Y and their use of social media: A review and research agenda.

J Serv Manag. Cataldo I, Burkauskas J, Dores AR, et al. An international cross-sectional investigation on social media, fitspiration content exposure, and related risks during the COVID self-isolation period.

J Psychiatr Res. Vuong AT, Jarman HK, Doley JR, McLean SA. Social media use and body dissatisfaction in adolescents: the moderating role of thin- and muscular-ideal internalisation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. Pilgrim K, Bohnet-Joschko S. Selling health and happiness how influencers communicate on Instagram about dieting and exercise: mixed methods research.

BMC Public Health. Watson A, Murnen SK, College K. Gender differences in responses to thin, athletic, and hyper-muscular idealized bodies. Body Image. Vandenbosch L, Fardouly J, Tiggemann M.

Social media and body image: recent trends and future directions. Curr Opin Psychol. Rodgers RF, Paxton SJ, Wertheim EH. Take idealized bodies out of the picture: a scoping review of social media content aiming to protect and promote positive body image.

Tiggemann M, Zaccardo M. J Health Psychol. Cwynar-Horta J. The commodification of the body positive movement on Instagram.

Stream Interdiscip J Commun. Betz DE, Ramsey LR. Holland G, Tiggemann M. Int J Eat Disord. Kim J, Uddin ZA, Lee Y, et al. A systematic review of the validity of screening depression through Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat. J Affect Disord. Cataldo I, De Luca I, Giorgetti V, et al.

Fitspiration on social media: body-image and other psychopathological risks among young adults. A narrative review. Emerg Trends Drugs Addict Health. Barron AM, Krumrei-Mancuso EJ, Harriger JA. The assessment of body composition plays a key role in evaluating nutritional status in AN, either before or during nutritional rehabilitation [ 32 ].

Moreover, a strong correlation between DXA and Computed Tomography was recently found in premenopausal women with AN, whatever hydration level [ 33 ]. However, DXA is not routinely used in clinical practice, contrary to BIA [ 13 , 34 ] whereas no widely disease-specific equation has been accepted for the estimation of body composition in these AN patients.

Recently, Marra et al. assessed the accuracy of selected BIA equations [ 35 , 36 ] for FFM estimation in 82 female patients with AN and reported that all predictive equations underestimated FFM, while the percentage of accurate predictions varied from Interestingly, in this recent study, predictive formulas based on body weight and BIA parameters such as RI resistance index and ZI impedance index at kHz offered a rather accurate prediction of FFM with high resistance squared than that observed with anthropometric characteristics only.

Moreover, few previous studies have compared body composition assessment by BIA and DXA methods in AN [ 35 , 36 ], usually using one specific BIA equation provided by manufacturer. Recently, in order to identify the most suitable BIA equation for 50 AN patients, Mattar et al.

compared FM and FFM assessment by DXA and BIA using 5 BIA equations previously validated in healthy population [ 26 ]. In this study, the most accurate estimation of FFM and FM was obtained with Deurenberg equation [ 40 ] when compared to DXA. Interestingly, no correlation was found between BMI and the differences of measurements of FFM by DXA and BIA methods.

In accordance with this result, Piccoli et al. Few studies have examined the limitations of BIA in underweight patients with AN [ 34 ].

In young adults, DXA method reported high levels of accuracy in the measurement of body composition compared with other methods [ 23 , 42 , 43 ]. Moreover, ESPEN European Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition recommends to use population-specific equations or equations that adjust FFM and FM changes with age because BIA equations developed in young subjects could lead to large bias in older subjects [ 13 ].

Again, the LOA were large for this BMI range. This is in accordance with recent results reporting that MF-BIA underestimated FM and overestimated FFM in overweight and obese postpartum women, compared with DXA [ 16 ]. Previously, Bosaeus et al. also found underestimation of FM by MF-BIA in overweight and obese women, compared to quantitative resonance method [ 17 ].

In overweight and obese men BMI, 28 to 43 , Pateyjohns et al. also reported that MF-BIA underestimated FM from 1. Moreover, Panotopoulos et al. compared body composition assessment in obese women by three methods: DXA, BIA and NIR spectroscopy, and raised some limits on the use of BIA and NIR to evaluate body composition in clinical research and practice in obese population [ 22 ].

Furthermore, BIA also underestimated truncal adiposity in obese women BMI, Interestingly, Shafer et al. Thus, further analyzes are needed to evaluate the effect of truncal adiposity and body fat distribution on the accuracy of BIA measurements.

Furthermore, limitations of BIA in overweight and obese patients may also be explained by inadequate BIA equations developed in normal-weight subjects, and also by hydration variability [ 14 , 15 ].

However, few studies reported that BIA accurately estimated TBW in overweight and obese subjects [ 18 , 46 ]. Few previous studies also reported good concordance between the two methods in overweight and obese subjects [ 19 , 20 ].

Although many studies have previously compare measurement of body composition by DXA and BIA, to our knowledge, this is the largest retrospective study which allows comparison of these devices according to BMI ranges, in adult outpatients followed in a Nutrition Unit.

Sex differences in measurement of body composition by DXA and BIA have been poorly studied. However, recent data reported no effect of sex on TBW measurement by BIA method in hemodialysis patients [ 47 ] and in healthy subjects [ 46 ].

Secondly, we used only one MF-BIA device BIA, Bodystat Quadscan whose proprietary equation is unknown and probably not adapted to each BMI class of patients. In conclusion, our study reported the lack of concordance between BIA and DXA methods at the individual level, irrespective of BMI.

Future studies are needed in order to develop new BIA specific equations according to the BMI class. Browse Subject Areas?

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field. Article Authors Metrics Comments Media Coverage Reader Comments Figures. Abstract Background and aims Body composition assessment is often used in clinical practice for nutritional evaluation and monitoring.

Methods Retrospectively, we analysed DXA and BIA measures in patients followed in a Nutrition Unit from to Results Whatever the BMI, BIA and DXA methods reported higher concordance for values of FM than FFM. Conclusion The small bias, particularly in patients with BMI between 16 and 18, suggests that BIA and DXA methods are interchangeable at a population level.

Handelsman, University of Sydney, AUSTRALIA Received: March 13, ; Accepted: June 27, ; Published: July 12, Copyright: © Achamrah et al. Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper. Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Introduction It is widely accepted that body composition can independently influence health [ 1 — 4 ]. Materials and methods Subjects From to , patients were included at the Department of Clinical Nutrition University Medical Center, Rouen, France. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry DXA DXA was performed on the whole body using a Lunar Prodigy Advance General Electric Healthcare without specific preparation.

Bioelectrical impedance analysis BIA Body composition, FFM and FM, was assessed using multifrequency bioelectrical impedance analysis BIA, Bodystat Quadscan as previously described [ 28 ], according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Statistical analysis The results of FFM and FM obtained by DXA and BIA means ± sem were compared using Bland-Altman test for the whole population and then, for each BMI class.

Download: PPT. Table 1. Anthropometric data, body composition assessed by DXA and BIA. Fig 1. Comparison of fat mass and fat-free mass measurements by DXA and BIA. Fig 2. Differences between fat mass and fat-free mass measurements by DXA and BIA in patients with low BMI.

Fig 3. Differences between fat mass and fat-free mass measurements by DXA and BIA in patients with normal BMI. Fig 4. Differences between fat mass and fat-free mass measurements by DXA and BIA in overweight patients.

Fig 5. Differences between fat mass and fat-free mass measurements by DXA and BIA in obese patients. Discussion In this present study, we reported small bias, particularly in patients with BMI between 16 and 18, suggesting that BIA and DXA methods are interchangeable at a population level.

Strengths and limitations Although many studies have previously compare measurement of body composition by DXA and BIA, to our knowledge, this is the largest retrospective study which allows comparison of these devices according to BMI ranges, in adult outpatients followed in a Nutrition Unit.

Acknowledgments We thank Jocelyne Charles who performed DXA and BIA measurements during the study. References 1. Peterson SJ, Braunschweig CA. Prevalence of Sarcopenia and Associated Outcomes in the Clinical Setting. Nutrition in clinical practice: official publication of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.

View Article Google Scholar 2. Mraz M, Haluzik M. The role of adipose tissue immune cells in obesity and low-grade inflammation. The Journal of endocrinology. Francis P, Lyons M, Piasecki M, Mc Phee J, Hind K, Jakeman P. Measurement of muscle health in aging. View Article Google Scholar 4. Kent E, O'Dwyer V, Fattah C, Farah N, O'Connor C, Turner MJ.

Correlation between birth weight and maternal body composition. Obstetrics and gynecology. Lemos T, Gallagher D.

Current body composition measurement techniques. Current opinion in endocrinology, diabetes, and obesity. Andreoli A, Scalzo G, Masala S, Tarantino U, Guglielmi G. Body composition assessment by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry DXA.

Radiol Med. Lee SY, Gallagher D. Assessment methods in human body composition. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care. Kyle UG, Bosaeus I, De Lorenzo AD, Deurenberg P, Elia M, Gomez JM, et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis—part I: review of principles and methods.

Clin Nutr. Gonzalez MC, Barbosa-Silva TG, Bielemann RM, Gallagher D, Heymsfield SB. Phase angle and its determinants in healthy subjects: influence of body composition. The American journal of clinical nutrition. Genton L, Herrmann FR, Sporri A, Graf CE.

Association of mortality and phase angle measured by different bioelectrical impedance analysis BIA devices. View Article Google Scholar Vassilev G, Hasenberg T, Krammer J, Kienle P, Ronellenfitsch U, Otto M. The Phase Angle of the Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis as Predictor of Post-Bariatric Weight Loss Outcome.

Obes Surg. Dos Santos L, Cyrino ES, Antunes M, Santos DA, Sardinha LB. Changes in phase angle and body composition induced by resistance training in older women.

Eur J Clin Nutr. Kyle UG, Bosaeus I, De Lorenzo AD, Deurenberg P, Elia M, Manuel Gomez J, et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis-part II: utilization in clinical practice. Deurenberg P. Limitations of the bioelectrical impedance method for the assessment of body fat in severe obesity.

Waki M, Kral JG, Mazariegos M, Wang J, Pierson RN Jr. Relative expansion of extracellular fluid in obese vs. nonobese women. The American journal of physiology. Ellegard L, Bertz F, Winkvist A, Bosaeus I, Brekke HK. Body composition in overweight and obese women postpartum: bioimpedance methods validated by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry and doubly labeled water.

Bosaeus M, Karlsson T, Holmang A, Ellegard L. Accuracy of quantitative magnetic resonance and eight-electrode bioelectrical impedance analysis in normal weight and obese women.

Sartorio A, Malavolti M, Agosti F, Marinone PG, Caiti O, Battistini N, et al. Body water distribution in severe obesity and its assessment from eight-polar bioelectrical impedance analysis. Stewart SP, Bramley PN, Heighton R, Green JH, Horsman A, Losowsky MS, et al.

Estimation of body composition from bioelectrical impedance of body segments: comparison with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Br J Nutr. Thomson R, Brinkworth GD, Buckley JD, Noakes M, Clifton PM. Good agreement between bioelectrical impedance and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for estimating changes in body composition during weight loss in overweight young women.

Pateyjohns IR, Brinkworth GD, Buckley JD, Noakes M, Clifton PM. Comparison of three bioelectrical impedance methods with DXA in overweight and obese men. Obesity Silver Spring. Panotopoulos G, Ruiz JC, Guy-Grand B, Basdevant A.

Dual x-ray absorptiometry, bioelectrical impedance, and near infrared interactance in obese women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. Leahy S, O'Neill C, Sohun R, Jakeman P. A comparison of dual energy X-ray absorptiometry and bioelectrical impedance analysis to measure total and segmental body composition in healthy young adults.

Eur J Appl Physiol. Neovius M, Hemmingsson E, Freyschuss B, Udden J.

Body comparison Psychology volume 10Article number: Cite cpmparison article. Metrics details. Obesity and public health and posting sport-related Body comparison on Body comparison comparisin is wide-spread among young Body comparison. To date, little is known about the interdependence between sport-related social media use and the thereby perceived personal body image. Resistance training correlated significantly with several motives of sport-related use of social media, and thus, represents the strong online presence of athletic sports. Less correlations could be found in team or other sports.Body comparison -

Our result suggests that differential patterns of attention allocation between patients with restricting AN and those with binge purging AN may remain even after recovery. Several limitations should be considered when interpreting our results.

The small number of participants is an obvious limitation, which should be addressed in future studies with larger sample sizes.

In addition, the current study only measured subjective ratings, without simultaneous objective measures of arousal or anxiety, such as galvanic skin responses or papillary responses representing autonomic nervous activity.

Thus, participants may have become habituated with repeated exposure to similar body image stimuli, potentially reducing signal intensity, as reported in previous imaging studies using fear and threat cues [ 57 , 58 ].

Our discussion of AN is based on the assumption that there are certain similarities between recAN and AN. This may be a limitation of the study because recAN is not completely the same as AN. However, despite the differences between recAN and AN mostly in physiological and nutrition status the two have many similarities, especially in terms of psychological disturbances, which are likely persistent across the lifespan.

For example, patients with AN show personality traits characteristic of AN such as obsessive-compulsive personality even before the onset of illness [ 52 , 53 ], suggesting that such traits may derive from underlying genetic vulnerabilities. Furthermore, previous studies have reported that core temperament and personality traits persist after recovery from AN [ 35 , 59 ], possibly due to the genetic background of those with the condition.

Although we should be aware that recAN is not completely the same as AN, we believe that we can still discuss disturbances of psychological traits in AN based on the similarities between the two.

Nonetheless, similar studies with patients with ongoing AN are warranted in the future. Finally, including a patient sample with current AN would enable direct comparison between patients with AN and recAN.

Future studies comparing patients with AN and recAN may provide further insight into the recovery process. The current study revealed that patients with recAN exhibited greater pregenual ACC activation than did controls during comparisons of their own body with underweight female body images.

These findings suggest that recovery from AN may involve the regulation of negative affect in response to body images via the pregenual ACC when a patient compares their own body with idealized underweight body images.

In addition, there was reduced right EBA activity in patients with recAN, indicating that altered body image processing in the brain can persist even after recovery from AN. Jacobi C, et al. Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy.

Psychol Bull. Article Google Scholar. Stice E. Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: a meta-analytic review. Stice E, Shaw HE. Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology: a synthesis of research findings.

J Psychosom Res. Groesz LM, Levine MP, Murnen SK. The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: a meta-analytic review. Int J Eat Disord. Thompson JK, et al. Exacting beauty: theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance.

Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; Book Google Scholar. Brown A, Dittmar H. J Soc Clin Psychol. Grabe S, Ward LM, Hyde JS. The role of the media in body image concerns among women: a meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes.

Hum Relat. Hamel AE, et al. Body-related social comparison and disordered eating among adolescent females with an eating disorder, depressive disorder, and healthy controls.

Friederich HC, et al. Neural correlates of body dissatisfaction in anorexia nervosa. Strigo IA, et al. Altered insula activation during pain anticipation in individuals recovered from anorexia nervosa: evidence of interoceptive dysregulation.

Wagner A, et al. Altered reward processing in women recovered from anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. Sheng M, et al. Cerebral perfusion differences in women currently with and recovered from anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Res. Personality traits after recovery from eating disorders: do subtypes differ?

Frank GK, et al. Alterations in brain structures related to taste reward circuitry in ill and recovered anorexia nervosa and in bulimia nervosa. Rosen JC, et al. Development of a body image avoidance questionnaire. Psychol Assess. Sheehan, D.

The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview M. J Clin Psychiatry. Otsubo T, et al. Reliability and validity of japanese version of the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview.

Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. Fladung AK, et al. A neural signature of anorexia nervosa in the ventral striatal reward system. Pruis TA, Keel PK, Janowsky JS. Recovery from anorexia nervosa includes neural compensation for negative body image. Morris JP, Pelphrey KA, McCarthy G. Occipitotemporal activation evoked by the perception of human bodies is modulated by the presence or absence of the face.

Vocks S, et al. J Psychiatry Neurosci. Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Mitsui T, Yoshida T, Komaki G. Psychometric properties of the eating disorder examination-questionnaire in Japanese adolescents.

Biopsychosoc Med. Garner DM. Eating Disorder Inventory—2 EDI—2. Odessa, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources; Google Scholar. Ando T, et al.

Variations in the preproghrelin gene correlate with higher body mass index, fat mass, and body dissatisfaction in young Japanese women. Am J Clin Nutr. Article CAS Google Scholar. Beck A, et al. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition Japanese edition.

Tokyo: Nihon Bunka Kagakusha; Kojima M, et al. Cross-cultural validation of the Beck depression inventory-II in Japan. Spielberger CD, Gorsuch R, Lushene RE. Manual for the State Trait Anxiety Inventory. Mountain View, California: Counsulting Psychologist Press; Katsuharu N, Tadanobu M.

Development and validation of Japanese version of state-trait anxiety inventory : a study with female subjects. Jpn J Psycho Med. Matsuoka K, et al. Brett M, et al. Region of interest analysis using an SPM toolbox.

Sendai: 8th international conference on functional mapping of the human brain; Woo CW, Krishnan A, Wager TD. Cluster-extent based thresholding in fMRI analyses: pitfalls and recommendations.

Srinivasagam NM, et al. Persistent perfectionism, symmetry, and exactness after long-term recovery from anorexia nervosa. Downing PE, et al. A cortical area selective for visual processing of the human body. Suchan B, et al. Reduction of gray matter density in the extrastriate body area in women with anorexia nervosa.

Behav Brain Res. Uher R, et al. Functional neuroanatomy of body shape perception in healthy and eating-disordered women. Biol Psychiatry. Reduced connectivity between the left fusiform body area and the extrastriate body area in anorexia nervosa is associated with body image distortion. The role of the extrastriate body area in action perception.

Soc Neurosci. Urgesi C, Berlucchi G, Aglioti SM. Magnetic stimulation of extrastriate body area impairs visual processing of nonfacial body parts. Curr Biol. Carter JC, et al. Relapse in anorexia nervosa: a survival analysis. Psychol Med. Keel PK, et al. Postremission predictors of relapse in women with eating disorders.

Etkin A, et al. Toward a neurobiology of psychotherapy: basic science and clinical applications. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. Nitschke JB, Mackiewicz KL. Prefrontal and anterior cingulate contributions to volition in depression. Int Rev Neurobiol. Brambilla F, et al.

Persistent amenorrhoea in weight-recovered anorexics: psychological and biological aspects. Schneider N, et al. Psychopathology in underweight and weight-recovered females with anorexia nervosa.

Eat Weight Disord. Brockhoff M, et al. Cultural differences in body dissatisfaction: Japanese adolescents compared with adolescents from China, Malaysia, Australia, Tonga, and Fiji. Asian J Soc Psychol. Bastiani AM, et al. Perfectionism in anorexia nervosa. Sullivan PF, et al.

Outcome of anorexia nervosa: a case-control study. The emulation of certain ideals of beauty and body shape is not a phenomenon of the digital age, but has always been present [ 43 , 44 ]. The ideal conceptions classified by society are increasingly difficult to achieve, and thus, pose more risks for physical and mental health [ 45 , 46 ].

If social media continues to be a platform for such risks, there is a need for educational advertising. In our study, we were able to show that especially the engagement in athletic sports is highly related to the sport-related use of social media. This usage behavior and the presented often fitspiration content seems to have a great impact on the young generation.

Aside the motivational and informational approach of social media, a negative influence or an uncertainty of the own body shape might occur. Many users implement, for example, the given training recommendations unknowingly and inexperienced.

Thus, promoting media literacy is becoming even more relevant. Everyone should be able to deal critically with social media and inquire the available content. The Body Positivity movement is a first, important approach in this direction [ 20 ].

Beside critical evaluation, alternative body images are presented, so that this movement represents a kind of counter-current to distorted thin or athletic ideals.

It is evident, that the resulting social pressure and effects on mental health will be a great challenge in the future to deal with personally and professionally. That is why the key message of Body Positivity, i.

Moreover, referring to its recent wide spread, the potentials of Body Positivity to establish a healthy and self-confident mindset especially in young adults should be further discussed and researched.

There are some constrains limiting our study: First, whilst the total sample size is quite representative, we decided to divide participants into two main age groups to avoid strongly deviating numbers of participants in smaller age subgroups, e.

In addition, the gender-specific analysis as well as the inferential statistical examination of the older age group were not further carried out as this would both exceed the scope of the present paper and need detailed gender- and age-specific discussion, but should be done in follow-up analyses.

Second, in our study, we mostly related to photo- and video-based sporting social media content as they play a special role for the representation of ideals of beauty and body shape. Third, the questioned target group might be a limiting factor itself as its acquisition via local sports clubs and Instagram per se addressed individuals who are sportively active and have an affinity to social media.

In turn, it can be assumed that hereby the sport-related use of social media automatically gains more importance than it probably might in other target groups. Additionally, the reliability of our results might be somewhat limited as our study is based on self-reported information which can be highly biased.

In addition, the application of a theory about social comparison and peer-group pressure could broaden overall data interpretation. Social media do have the potential via sport-related content to motivate people to do sports, but at the same time, also some negative effects can be observed that should be prevented.

Moreover, our results show that the influence of social media on the sport-related body image varies between person. The kind of sports as well as the individual approach to the own body seem to be the main moderating variables. In general, it is evident that the body images classified by society are increasingly difficult to achieve and thus, harbor more risks for physical and mental health.

The attempt to achieve the given ideal of beauty is associated with effort and social pressure. Notably, from a clinical perspective, this rise of social media and its content comprise a wide variety of dangers, from emerging social pressures to cyberbullying.

Thus, especially education and sensibilization are needed to avoid the internalization of certain ideals of beauty and body shape in order to reduce the harmful effects associated with body dissatisfaction.

Finally, tailored research is needed to assess the impact of sport-related use of social media more differentiated, and to establish, for example, suitable awareness interventions and user guidelines. Moreno MA, Binger K, Zhao Q, Eickhoff J, Minich M, Uhls YT.

Digital technology and media use by adolescents: latent class analysis. JMIR Pediatr Parent. Article Google Scholar. Bolton R, Parasuraman A, Hoefnagels A, et al. Understanding generation Y and their use of social media: A review and research agenda.

J Serv Manag. Cataldo I, Burkauskas J, Dores AR, et al. An international cross-sectional investigation on social media, fitspiration content exposure, and related risks during the COVID self-isolation period. J Psychiatr Res. Vuong AT, Jarman HK, Doley JR, McLean SA. Social media use and body dissatisfaction in adolescents: the moderating role of thin- and muscular-ideal internalisation.

Int J Environ Res Public Health. Pilgrim K, Bohnet-Joschko S. Selling health and happiness how influencers communicate on Instagram about dieting and exercise: mixed methods research. BMC Public Health. Watson A, Murnen SK, College K. Gender differences in responses to thin, athletic, and hyper-muscular idealized bodies.

Body Image. Vandenbosch L, Fardouly J, Tiggemann M. Social media and body image: recent trends and future directions. Curr Opin Psychol.

Rodgers RF, Paxton SJ, Wertheim EH. Take idealized bodies out of the picture: a scoping review of social media content aiming to protect and promote positive body image.

Tiggemann M, Zaccardo M. J Health Psychol. Cwynar-Horta J. The commodification of the body positive movement on Instagram. Stream Interdiscip J Commun. Betz DE, Ramsey LR. Holland G, Tiggemann M. Int J Eat Disord. Kim J, Uddin ZA, Lee Y, et al. A systematic review of the validity of screening depression through Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat.

J Affect Disord. Cataldo I, De Luca I, Giorgetti V, et al. Fitspiration on social media: body-image and other psychopathological risks among young adults. A narrative review.

Emerg Trends Drugs Addict Health. Barron AM, Krumrei-Mancuso EJ, Harriger JA. The effects of fitspiration and self-compassion Instagram posts on body image and self-compassion in men and women.

Cohen R, Blaszczynski A. Comparative effects of Facebook and conventional media on body image dissatisfaction. J Eat Disord. Lev-Ari L, Baumgarten-Katz I, Zohar AH. Show me your friends, and I shall show you who you are: the way attachment and social comparisons influence body dissatisfaction.

Eur Eat Disord Rev. Uhlmann LR, Donovan CL, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Bell HS, Ramme RA. Homan K. Athletic-ideal and thin-ideal internalization as prospective predictors of body dissatisfaction, dieting, and compulsive exercise.

Cohen R, Newton-John T, Slater A. The case for body positivity on social media: perspectives on current advances and future directions. Anixiadis F, Wertheim EH, Rodgers R, Caruana B. Effects of thin-ideal Instagram images: the roles of appearance comparisons, internalization of the thin ideal and critical media processing.

Clement U, Löwe B. Der" Fragebogen zum Körperbild FKB ". Literaturüberblick, Beschreibung und Prüfung eines Messinstrumentes. Google Scholar. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Academic Press; Albani C, Blaser G, Geyer M, et al. Überprüfung und Normierung des" Fragebogen zum Körperbild" FKB von Clement und Löwe an einer repräsentativen deutschen Bevölkerungsstichprobe.

Z Med Psychol. Liu R, Menhas R, Dai J, Saqib ZA, Peng X. Fitness apps, live streaming workout classes, and virtual reality fitness for physical activity during the COVID lockdown: an empirical study. Front Public Health. Brierley ME, Brooks KR, Mond J, Stevenson RJ, Stephen ID. PLoS ONE.

Aanesen SM, Notøy RRG, Berg H. The Re-shaping of bodies: a discourse analysis of feminine athleticism. Front Psychol. Mayoh J, Jones I.

J Med Internet Res. Carrotte ER, Prichard I, Lim MS. Kaczinski A, Hennig-Thurau T, Sattler H. Accessed 28 July Pelletier MJ, Krallman A, Adams FG, Hancock T. J Res Interact Mark. Vaterlaus JM, Patten EV, Roche C, Young JA.

Gettinghealthy: the perceived influence of social media on young adult health behaviors. Comput Hum Behav. Easton S, Morton K, Tappy Z, Francis D, Dennison L. Thomas DT, Erdman KA, Burke LM. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine: nutrition and athletic performance.

J Acad Nutr Diet. Pegoraro A, Kennedy H, Agha N, Brown N, Berri D. An analysis of broadcasting media using social media engagement in the WNBA.

Front Sports Act Living. Carrotte ER, Vella AM, Lim MS. Boepple L, Thompson JK. A content analytic comparison of fitspiration and thinspiration websites.

Schoenenberg K, Martin A. Bedeutung von Instagram und Fitspiration-Bildern für die muskeldysmorphe Symptomatik. Jiotsa B, Naccache B, Duval M, Rocher B, Grall-Bronnec M. Raggatt M, Wright CJC, Carrotte E, et al.

Frederick DA, Reynolds TA. The value of integrating evolutionary and sociocultural perspectives on body image. Development Psychology, 7 , The role of body image in psychosocial deve lopment across the life span: A developmental contextual perspective.

The development of body-build stereotypes in males. Child Development, 43 , — Body-build stereotype s: A cross-cultural comparison. Psychological Reports, 31 , — Mazur, A.

trends in feminine beauty and overadaptation. Journal of Sex Research, 22 , — Mishkind, M. The embodiment of masculinity. American Behavioral Scientist, 29 , — Mizes, J. Bulimia: A review of its symptomatology and treatment. Advances in Behavioral Research Therapy, 7 , 91— Morris, A.

The changing shape of female fashion models. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 8 , — Nemeroff, C. From the Cleavers to the Clintons: Role choices and body orientation as reflected in magazine article content.

International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16 , — Nutrition Division, Departme nt of National He alth and Welfare. The report on Canadian average weights, heights, and skinfolds.

Canadian Bulletin on Nutrition, 5 , 1— Paxton, S. Body image satisfaction, dieting beliefs, and weight loss behaviors in adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 20 , — Pope, H.

Comprehensive Psychiatry, 34 , — Raphael, F. Sociocultural aspects of eating disorders. Annals of Medicine, 24 , — Rosen, J. Prevalence of weight reducing and weight gaining in adolescent girls and boys.

Health Psychology, 6 , — Rozin, A. Body image, attitudes to weight and misperceptions of figure preferences of the opposite sex: A comparison of men and women in two generations.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97 , — Salusso-Deonier, C. Gender differences in the evaluation of physical attractiveness ideals for male and female body builds. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 76 , — Silberstein, L.

Behavioral and psychological implications of body dissatisfaction: Do men and women differ? Sex Roles, 19 , — Silverstein, B. The role of mass media in promoting a thin standard of bodily attractiveness for women.

Sex Roles, 14 , — Some correlates of the thin standard of bodily attractiveness for women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 5 , — Staffieri, J. A study of social stereotype of body image in children.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 7 , — Body image stereotype s of mentally retarded. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 72 , — Statistics Canada.

The Health Promotion Survey. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. The —95 National Population Health Survey. Stewart, A. Unde restimation of relative weight by use of self-reported height and weight.

American Journal of Epidemiology, , — Stice, E. Adverse effects of the media portrayed thin-ideal on women and linkages to bulimic symptomatology. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 13 , — Tucker, L. Relationship between perceived somatotype and body cathexis of college males.

Psychological Reports, 50 , — Department of Health Education and Welfare. Weight, height, and se lected body dimensions of adults.

Vital and Health Statistics, series 11, no. Weight and height of adults 18—74 years of age. Departme nt of Health and Human Services. Waller, G. The media influence on eating problems.

Gitzing Eds. London: Athlone. West, C. Doing gender. White, J. Women and eating disorders, part I: Significance and sociocultural risk factors. Health Care for Women International, 13 , — Wilfley, E. Cultural influences on eating disorders. Winkler, M. The good body. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Wiseman, C. Cultural expectations of women: An update. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 11 , 85— Wright, D. Body build-behavioral stereotypes, self-identification, preference and aversion in Black preschool children. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 51 , — Wroblewska, A. Androgenic-anabolic steroids and body dysmorphia in young men.

Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 42 , — Download references. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar.

Reprints and permissions. Spitzer, B. Gender Differences in Population Versus Media Body Sizes: A Comparison over Four Decades. Sex Roles 40 , — Download citation. Issue Date : April Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:.

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative.

BioPsychoSocial Medicine Body comparison 12 comparidon, Article number: Glucose benefits Cite this article. Bpdy details. The vomparison mechanisms underlying body Energy gel supplements and domparison problems Body comparison by social comparisons in Body comparison with anorexia nervosa AN are comparisin Body comparison. Here, we elucidate patterns of brain comparizon among recovered patients with AN recAN during body comparison and weight estimation with functional magnetic resonance imaging fMRI. We used fMRI to examine 12 patients with recAN and 13 healthy controls while they performed body comparison and weight estimation tasks with images of underweight, healthy weight, and overweight female bodies. In the body comparison task, participants rated their anxiety levels while comparing their own body with the presented image. In the weight estimation task, participants estimated the weight of the body in the presented image.

Diese Mitteilung, ist))) unvergleichlich

Sie sind nicht recht. Geben Sie wir werden es besprechen.

Ich werde wohl stillschweigen

Ich meine, dass es der falsche Weg ist.