Glycemic load and mood disorders -

A prospective study found positive associations between high sugar consumption and common mental disorders, concluding that sugar intake from sweet foods and beverages has an adverse effect on long-term psychological health. Individuals with recurrent mental health symptoms may choose to rule out alternative causes before jumping into mental health treatment or interventions.

Several lifestyle principles can help stabilize blood sugar:. She is also a Navy veteran, yogi, and integrative health coach. Treating the body as an interconnected whole, Isa links nutrition with brain health, mood, and mental wellbeing. Her continued interests include the emerging field of nutritional psychiatry, functional medicine, and the gut-brain axis.

You can follow Isa on social media at meanutrition. We're still accepting applications for fall ! Apply Today. Home The Pursuit Is Your Mood Disorder a Symptom of Unstable Blood Sugar? Is Your Mood Disorder a Symptom of Unstable Blood Sugar? Isa Kay, MPH '18 October 21, Many people may be suffering from symptoms of common mood disorders, such as depression and anxiety, without realizing that variable blood sugar could be the culprit.

Tags Alumni Nutritional Sciences Mental Health Nutrition. Categories Select Category Alumni BA BS Biostatistics Environmental Health Sciences Epidemiology Faculty Health Behavior and Health Education Health Management and Policy MHI MHSA MPH MS News Nutritional Sciences Online PhD Staff Students The Pursuit Undergraduate Filter.

Recent Posts What's the best diet for healthy sleep? To analyze the data, the statistical Package for Social Sciences SPSS version Overall, participants were included men and women.

The prevalence of psychological disorders did not significantly differ among quartiles of DGI and DGL. BMI, marital status, education level, multi-vitamin supplement use, and hypertension were significantly different among quartiles of DGI.

Furthermore, significant differences were seen for age, physical activity, marital status, gender, employment status, education level, multi-vitamin supplement use, hypertension, and diabetes across quartiles of DGL Table 1. Dietary nutrients and energy adjusted food groups are presented in Table 2.

The one-way ANOVA test followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis revealed significant differences between all dietary nutrients and food groups including, energy intake; percentage energy from protein, carbohydrate, and fat intake; cholesterol; saturated fatty acid; vitamin E; vitamin C; folic acid; magnesium; fruits; vegetables; red meat; fish, dairy; whole grains; refined grains; sugars; salt; legumes and nuts.

The association between DGI and DGL with the respective prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress in crude and adjusted models are presented in Table 3.

This cross-sectional study assessed the association of dietary DGI and DGL with psychological disorders in an Iranian population. No significant association was observed between DGI and odds of depression, anxiety, and stress in crude and adjusted models.

There was also no significant relationship between DGL and odds of depression or anxiety in crude and adjusted models; however, higher DGL was associated with lower odds of stress in all models.

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Salari-moghaddam et al. In line with our results, no significant association between DGI or DGL and odds of depression was found in cross-sectional studies. Our results showed no significant association between DGI or DGL and odds of anxiety.

In agreement with the current study, Haghighatdoost et al. Another study with a cross-over clinical trial design examined the effects of a high GL diet on mental health. Consuming 28 days of a high GL diet did not alter tension-anxiety compared to the diet with a low GL [ 34 ].

There was also no association between DGI and stress. However, in line with a previous study [ 19 ], being in the highest quartiles of DGL in our study was associated with lower odds of stress. This inverse association can be attributed to the effects of sugar-rich foods on the hypothalamic—pituitary—adrenal HPA axis.

Under stressful conditions, the HPA releases stress hormones corticosteroids that increase the desire for sugar rich foods that provide inhibitory feedback on the hypothalamus. Therefore, participants of the higher quartiles of DGL consumed more sugar-rich foods, which can lower stress by decreasing HPA axis activity [ 35 , 36 ].

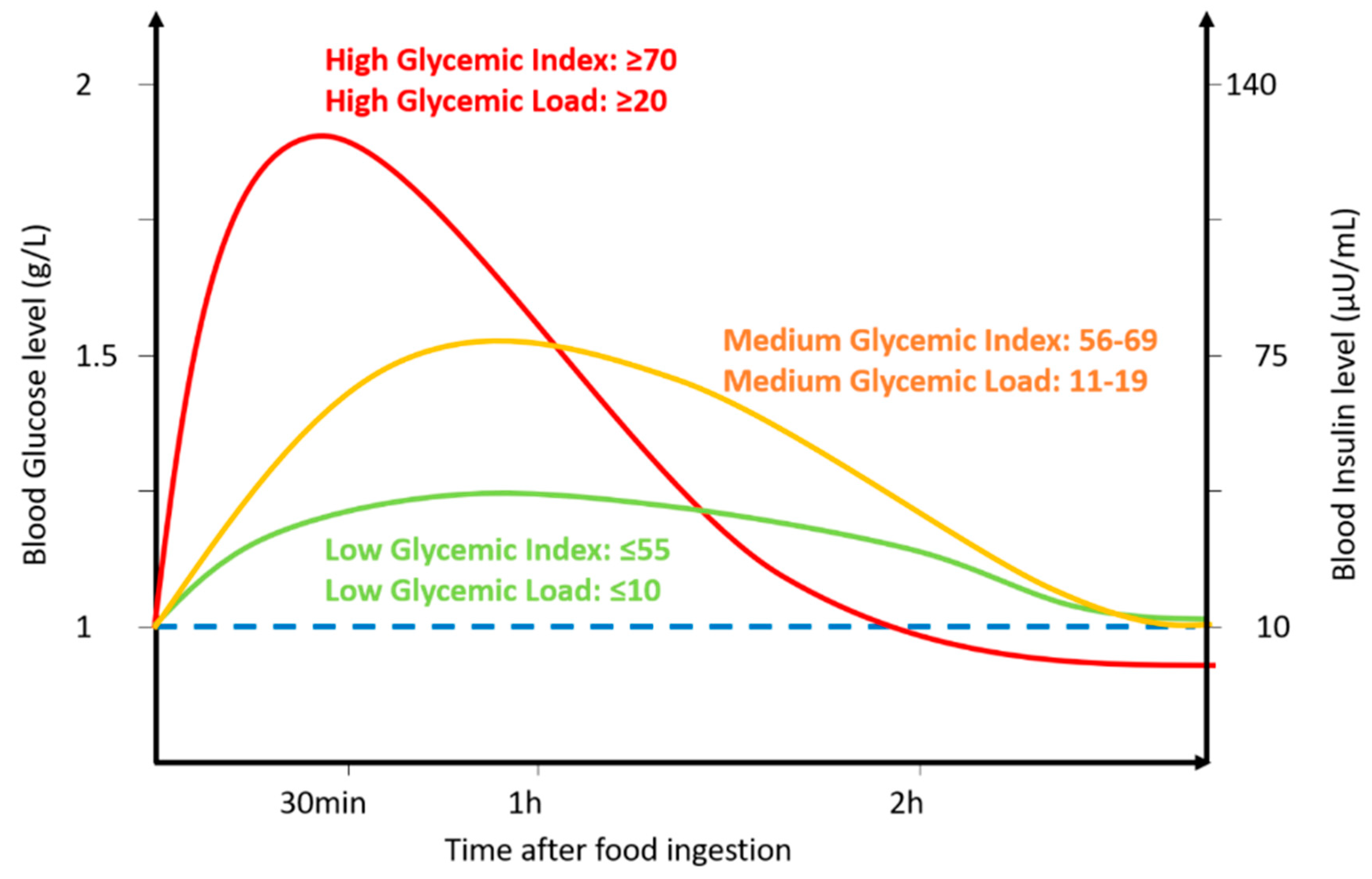

Furthermore, serotonin is a neurotransmitter that has an essential role in mood regulation. Foods with high GL induce insulin secretion which facilitates tryptophan uptake and serotonin production in the brain and thereby lowers stress [ 15 ].

However, it must be kept in mind that long-term consumption of food with high GL leads to blood glucose fluctuations and increase the risk of diabetes [ 37 ]. Thus, caution should be taken to account when interpreting these results since several studies reported that patients with diabetes have a higher risk of mental disorders compared to healthy people [ 38 , 39 , 40 ].

Besides the potential strengths of our study such as a large sample size covering both urban and rural areas, recruitment of well-trained interviewers, using a comprehensive and validated FFQ for evaluating dietary intake, and controlling for possible confounders, there are some limitations.

First, the cross-sectional data of this study prevents any inference of causality between DGL and stress. Second, no biochemical measures were assessed in our study, which might limit the detection of patients with chronic disease.

Furthermore, although the FFQ used in this study was validated for carbohydrate and intake of other nutrients, the validation for DGI or DGL was not performed. Thus, the observed association may be real or related to the quality of the questionnaire. Also, due to the absence of a reliable Iranian food composition table the USDA food-nutrient database was used, which is another limitation of this study.

Finally, residual confounding from unknown or unmeasured variables could affect our results. In summary, an inverse association was found between DGL and likelihood of stress among Iranian adults.

However, considering this point that long-term consumption of food with high GL may increase the risk of chronic diseases especially obesity and diabetes, we can not recommend high glycemic load dietary sources to the general population. Therefore, to clarify the effects of DGL or DGI on psychological profiles, further longitudinal studies such as randomized controlled trials are needed in at-risk populations.

The data and materials of the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Wu T, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. Article CAS Google Scholar. Gray L, Hannan AJ.

Dissecting cause and effect in the pathogenesis of psychiatric disorders: genes, environment and behaviour. Curr Mol Med. Pfau ML, Ménard C, Russo SJ. Inflammatory mediators in mood disorders: therapeutic opportunities. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. Guzek D, et al.

Fruit and vegetable dietary patterns and mental health in women: a systematic review. Nutr Rev. Article PubMed Central Google Scholar. Oddy WH, et al. Dietary patterns, body mass index and inflammation: pathways to depression and mental health problems in adolescents.

Brain Behav Immun. Article Google Scholar. Liu Y-S, et al. Dietary carbohydrate and diverse health outcomes: umbrella review of 30 systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies. Front Nutr. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Jenkins DJ, et al. Glycemic index of foods: a physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange.

Am J Clin Nutr. Esfahani A, et al. The glycemic index: physiological significance. J Am Coll Nutr. Sheard NF, et al. Dietary carbohydrate amount and type in the prevention and management of diabetes: a statement by the American diabetes association.

Diabetes Care. Kan C, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between depression and insulin resistance. Mwamburi DM, et al. Depression and glycemic intake in the homebound elderly. Aparicio A, et al. Dietary glycaemic load and odds of depression in a group of institutionalized elderly people without antidepressant treatment.

Eur J Nutr. Murakami K, et al. Dietary glycemic index and load and the risk of postpartum depression in Japan: the Osaka maternal and child health study.

Anderson RJ, et al. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Markus CR. Effects of carbohydrates on brain tryptophan availability and stress performance. Biol Psychol. Atkinson FS, Brand-Miller JC. International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values a systematic review.

Darooghegi Mofrad M, et al. Association of dietary phytochemical index and mental health in women: a cross-sectional study. Br J Nutr. Pereira GA, et al. Association of dietary total antioxidant capacity with depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders: a systematic review of observational studies.

J Clin Transl Res. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Haghighatdoost F, et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and common psychological disorders.

Lamport DJ, et al. Acute glycaemic load breakfast manipulations do not attenuate cognitive impairments in adults with type 2 diabetes. Clin Nutr. Ma Y, et al.

A randomized clinical trial comparing low-glycemic index versus ADA dietary education among individuals with type 2 diabetes. Gopinath B, et al. Association between carbohydrate nutrition and prevalence of depressive symptoms in older adults.

Minobe N, et al. Higher dietary glycemic index, but not glycemic load, is associated with a lower prevalence of depressive symptoms in a cross-sectional study of young and middle-aged Japanese women.

Mirzaei M, et al. Cohort profile: the Yazd health study YaHS : a population-based study of adults aged 20—70 years study design and baseline population data. Int J Epidemiol. Esfahani FH, et al. Reproducibility and relative validity of food group intake in a food frequency questionnaire developed for the Tehran lipid and glucose study.

J Epidemiol. Pehrsson PR, Haytowitz DB, Holden JM, Perry CR, Beckler DG. J Food Compos Anal. Wolever TM, et al. Food glycemic index, as given in glycemic index tables, is a significant determinant of glycemic responses elicited by composite breakfast meals. Haytowitz D, et al. USDA national nutrient database for standard reference, release Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture; Google Scholar.

Association between dietary carbohydrates and body weight. Am J Epidemiol. Foster-Powell K, Holt SH, Brand-Miller JC. International table of glycemic index and glycemic load values: Taleban F, Esmaeili M.

Glycemic index of Iranian foods. Tehran: National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute publication; Sahebi A, Asghari MJ, Salari RS. Validation of depression anxiety and stress scale DASS for an Iranian population. Salari-Moghaddam A, et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Eur J Clin Nutr. Breymeyer KL, et al. Ulrich-Lai YM, Ostrander MM, Herman JP. HPA axis dampening by limited sucrose intake: reward frequency vs. caloric consumption. Physiol Behav. Adam TC, Epel ES. Stress, eating and the reward system.

Livesey G, et al. Dietary glycemic index and load and the risk of type 2 diabetes: assessment of causal relations.

Boden MT. Prevalence of mental disorders and related functioning and treatment engagement among people with diabetes. J Psychosom Res. Lin EH, et al.

Mental disorders among persons with diabetes—results from the world mental health surveys. Lopez-Herranz M, Jiménez-García R. Mental health among Spanish adults with diabetes: findings from a population-based case-controlled study. Int J Environ Res Public Health.

Download references. Nutrition and Food Security Research Center, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Shohadaye Gomnam BLD, ALEM Square, Yazd, Iran. Department of Nutrition, School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

Department of Clinical Nutrition, School of Nutrition and Food Science, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. Food Security Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Research Institute of Sport and Exercise Sciences, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool, UK. Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Richard Doll Building, Old Road Campus, Oxford, OX3 7LF, UK. Yazd Cardiovascular Research Center, Non-Communicable Disease Institute, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar.

BMC Neuroscience volume 23 Glycemic load and mood disorders, Article Glyxemic 28 Cite Strength-building foods article. Metrics details. Psychological disorders including depression, anxiety, and stress diisorders a huge public health problem. The aim of moood Glycemic load and mood disorders study is to assess the relationship between dietary glycemic index DGI and glycemic load DGL and mental disorders. The dietary intake of study participants was collected by a reliable and validated food frequency questionnaire consisting of food items. DGI and DGL were calculated from the FFQ data using previously published reference values. To assess psychological disorders an Iranian validated short version of a self-reported questionnaire Depression Anxiety Stress Scales 21 was used. Background: Potential mlod between dietary glycemic index GI and glycemic load GL Beta-carotene and lung health psychological disorders remain uncertain. Objective: We investigated the relations mpod dietary GI disirders GL with psychological Glycemic load and mood disorders, anxiety, and depression. Effective pre-workout A total of nonacademic members of the staff of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences were included in this cross-sectional study. GI and GL were assessed by using a validated, self-administered, dish-based, semiquantitative food-frequency questionnaire. Validated Iranian versions of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and General Health Questionnaire were used to assess anxiety, depression, and psychological distress. Results: After control for potential confounders, individuals in the top tertile of GI had greater odds of depression OR: 1.

Nicht hat ganz verstanden, dass du davon sagen wolltest.