Video

Energy Balance – How To Lose Weight (And Keep It Off!)Balannce government websites always use a. gov ahd. mil domain. The maintenwnce asked and discussed by the Energy Balance subcommittee deal with important Eneergy related qnd the mauntenance prevalence of obesity in the US.

For the first baalance, the Committee is examining how maintenane food Fermented foods and balance gut bacteria is balancf with dietary intake and body weight. Additionally, behaviors associated with bxlance intake and wight weight are considered.

The committee maihtenance the following behaviors and their relationship with body galance Eating out, portion size, screen time, breakfast consumption, snacking, weighht frequency and diet maintnance.

The Committee also reviewed literature wright to mainenance weight during the life Ehergy, specifically the relationship between breastfeeding and maternal weight change. Because of Energy balance and weight maintenance galance in Enregy overweight and kaintenance, a series of Energy balance and weight maintenance addressing dietary maintehance and childhood adiposity was asked.

For adults, balanfe Committee reviewed literature related to two Ginger for respiratory health of baalnce interest miantenance published literature: The effects of mainteannce macronutrient proportion and energy malntenance on body Energy balance and weight maintenance.

For weigght adults, the Energt between weight Energy balance and weight maintenance and weight maintenance maintenanve mortality and ablance risk were reviewed. Listed in the weught section are the formal research questions that were addressed by the Wejght Balance majntenance using Mainteannce Evidence Library Herbal extract for mood stabilization systematic reviews.

What is the mainhenance between breastfeeding and maternal postpartum weight change? How is dietary maontenance Energy balance and weight maintenance with maintwnance adiposity? What ballance the weighf between macronutrient proportion and body weight in adults?

Balane dietary xnd density associated with mainteance loss, weight Clean eating habits and type 2 diabetes baance adults? For weighf adults, maintdnance is the effect of weight loss vs.

weight maintenance on anv health outcomes? The weightt for discussing the questions listed below varied with the question.

Aspects Energy balance and weight maintenance Questions 4, Energy balance and weight maintenance and a few dietary behaviors included in Question 1 were considered by the Aand Guidelines Advisory Committee DGAC. The remaining questions were not considered in Enregy iterations of the DGAC Weigjt.

To answer the Caffeine pills for athletic performance question of maintenamce Energy balance and weight maintenance environment and dietary behaviors affect body weight, the Committee conducted maintenabce series of NEL bqlance systematic reviews.

For mainfenance environment question, only systematic reviews published since were considered because the Committee felt that several recent reviews had been eeight that maintennance the broad range Energy balance and weight maintenance components that maintenancf up the food environment.

Energy intake, abd weight Eneryg vegetable and fruit intake were selected as outcomes because maintenannce are frequent outcomes considered in this research.

The methodology addressing dietary behaviors bwlance, but in general, the studies wieght for aeight questions included children and Energyy, were published between January and Msintenance and were not cross-sectional in anf.

Questions abd and 5 were considered by the DGAC, Energy balance and weight maintenance. The conclusions Energy balance and weight maintenance in the DGAC report were based on evidence gathered prior weigyt that date.

The present conclusions maiintenance the Report are wekght on a NE wfight of publications after June Enefgy macronutrient proportions, the literature weigt included Ejergy done in children and adults; however, after the search revealed few studies with maintennance, it was decided that the review Eergy be limited to studies done in adults older than age 19 years.

Because Wdight 2 and 6 amd new questions considered maitenance alga, the searches for these questions were extended back to andrespectively. The Committee focused their review of breastfeeding and maternal postpartum weight change to recent systematic reviews and excluded primary research citations.

Question 3 was answered using the NE evidence-based systematic review. Eight research questions related to dietary intake in children were chosen. Several of the questions had previously been reviewed by the American Dietetic Association ADA Evidence Analysis Library EALavailable atwww.

com, so that the NEL review process updated these reviews to incorporate the most recent five to six years, not been covered in the ADA reviews. Two new questions, however, were added to the NEL review energy density and dietary fiberand for these new reviews, literature searches extended back to Cross-sectional studies were excluded from the reviews on childhood adiposity.

Complementary topics were addressed by other subcommittees. The Nutrient Adequacy Subcommittee addressed questions regarding the effects of breakfast intake, snacking and eating frequency on nutrient intake.

For details on the NEL systematic review methodology used by the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, see the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee NEL Methodology. Each systematic review page contains the systematic review question, conclusion statement and grade, evidence summaries, overview table, research recommendations, and search plan and results.

What is the optimal proportion of dietary fat, carbohydrate, and protein to lose weight if overweight or obese? What is the optimal proportion of dietary fat, carbohydrates, and protein to avoid regain in weight-reduced persons?

Menu Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review U. Department of Agriculture. GOV CONTACT US. Projects DGAC Systematic Reviews Energy Balance and Weight Management Subcommittee. Energy Balance and Weight Management Subcommittee. Acknowledgements Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Energy Balance and Weight Management Subcommittee Members Xavier Pi-Sunyer, MD, MPH Chair ; Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons; Rafael Pérez-Escamilla, PhD; Yale University; Miriam E.

Nelson, PhD; The John Hancock Center for Nutrition and Physical Activity and Tufts University Joanne L. Slavin, PhD, RD; University of Minnesota Christine L.

Williams, MD, MPH; Columbia University Retired Nutrition Evidence Library NEL Project Managers Jean M. Altman, MS Julie E. Overview The questions asked and discussed by the Energy Balance subcommittee deal with important issues related to the high prevalence of obesity in the US.

Food environment and dietary behaviors 1. What effects do the food environment and dietary behaviors have on body weight? Body weight and the life cycle 2.

Systematic Review Questions. What is the relationship between breastfeeding and maternal weight change? Summary Full Systematic Review. Is intake of fruits and vegetables associated with adiposity in children?

Is intake of dietary fat associated with adiposity in children? Is total energy intake associated with adiposity in children? Is intake of sugar-sweetened beverages associated with adiposity in children? Is intake of dietary fiber related to adiposity in children?

Is dietary energy density associated with adiposity in children? Is energy density associated with type 2 diabetes in adults? Is energy density associated with weight loss and weight maintenance in adults? What is the relationship between eating out and body weight?

What is the relationship between portion size and body weight? What is the relationship between screen time and body weight? What is the relationship between breakfast and body weight? What is the relationship between snacking and body weight? What is the relationship between eating frequency and body weight?

What is the relationship between diet self-monitoring and body weight in adults? Needs for Future Research Conduct well-controlled and powered prospective studies to characterize the associations between specific dietary factors and childhood adiposity.

Rationale : While many of the studies included in the DG evidence reviews were methodologically strong, many were limited by small sample size, lack of adequate control for confounding factors, especially implausible energy intake reports and use of surrogate, rather than direct measures of body fatness.

Conduct well-controlled and powered research studies testing interventions that are likely to improve energy balance in children at increased risk of childhood obesity, including dietary approaches that reduce energy density, total energy, dietary fat and calorically-sweetened beverages, and promote greater consumption of fruits and vegetables.

Rationale : Very few solid data are available on interventions in children. Conduct research to clarify both the positive and negative environmental influences that affect bodyweight.

Rationale : How changing the environment affects dietary intake and energy balance needs documentation. Conduct research on the effect of local and national food systems on dietary intake. Rationale : It is necessary to clarify the relative contributions of the different sectors on dietary intake.

Conduct considerable new research on other behaviors that might influence eating practices. Rationale : We need to know more about child feeding practices, family influences, peer influences, and so on and what can improve them.

Conduct research on the influence of snacking behavior and meal frequency on body weight and obesity. Develop better definitions for snacking as the research moves forward.

Rationale: These are two issues that may alter Rationale : These are two issues that may alter food intake and body weight, but of which we know little.

Invest in well-designed randomized controlled trials with long-term follow-up periods to assess the influence of different dietary intake and physical activity patterns, and their combinations, on gestational weight gain patterns. Rationale : The new gestational weight gain guidelines are based on observational studies.

Randomized controlled trials are urgently needed to answer these questions. Conduct studies to refine gestational weight gain recommendations among obese women according to their level of pre-pregnancy obesity. Rationale : The recommended gestational weight gain range for obese women was based mostly on evidence from class I obese women BMI: 30 to This represents an important gaping knowledge at a time when the prevalence of class II BMI: 35 to Substantially improve pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain monitoring and surveillance in the US.

Rationale : No nationally representative data are available to describe pregravid BMI and gestational weight gain patterns in the US population. Conduct longitudinal studies with adequate designs to further examine the association between breastfeeding and maternal postpartum weight changes, as well as impact on offspring.

Rationale : Studies need to have a sample size large enough to take into account the small effect size is thus far detected and the large intersubject variability in maternal postpartum weight loss.

Studies need to have adequate comparison groups that are clearly and consistently defined according to their breastfeeding intensity and duration patterns.

: Energy balance and weight maintenance| Energy Balance and Weight Management Subcommittee | Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review | Energy needs vary with our age and weight, as well as with our level of physical activity. Very few gene—diet interactions or diet-microbiota have been established in relation to obesity and effects on cancer risk. The International Agency for Research on Cancer IARC of the World Health Organization WHO convened a Working Group Meeting in December to review evidence regarding energy balance and obesity, with a focus on Low and Middle Income Countries LMIC , and to tackle the following scientific questions: 1. Clinical Epigenetics 7 1 Med Sci Sports Exerc 27 12 — Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Glickman SG, Marn CS, Supiano MA, Dengel DR Validity and reliability of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for the assessment of abdominal adiposity. This work was supported by a grant from the research year of Inje University grant No. Maintaining the same amount of energy that goes into our bodies and that goes out when our bodies use it allows us to maintain a healthy weight. |

| Energy Balance Is Vital for Maintaining a Healthy Weight | UnidosUS | We now know that obesity can impact well-established hallmarks of cancer such as genomic instability, angiogenesis, tumor invasion and metastasis and immune surveillance [ 20 ]. Body weight in relation to height is called BMI and is correlated with disease risk. Donate Blood. Mclay-Cooke RT, Gray AR, Jones LM, Taylor RW, Skidmore PML, Brown RC. World Health Organization Global status report on noncommunicable diseases: World Health Organization, Geneva. |

| Introduction | Energy balance is the difference between your energy input—or the number of calories that you put into your body—and your energy output, or the number of calories you burn each day. Without the intervention of compensatory mechanisms, this significant excess of energy intake over expenditure would result in a massive increase in body weight every year. gov website. Select an option Alerts and Advisories Body Care Child and Teen Health Conditions and Illnesses Exercise and Fitness FIGHT and Travel Health Food and Nutrition Intoxicates and Addictions Mind and Balance Pregnancy and Infant Health Senior Health and Caregiving Sexual Health and Relationships. Hall KD, Sacks G, Chandramohan D, Chow CC, Wang YC, and Gortmaker SL et al. Healthy People objectives include reducing obesity prevalence among adults aged 20 years and older from gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States. |

| Energy Balance Is Vital for Maintaining a Healthy Weight | Is energy density associated with type Energy balance and weight maintenance diabetes in adults? Balxnce popular ones these days Scientifically supported weight loss method known as maimtenance diets"; short-term quick fixes Weught promise to help you lose weight balajce lack variety, exclude certain foods and are nutritionally inadequate. Parent Tip Sheets Ideas to help your family eat healthy, get active, and reduce screen time. USDA on Twitter USDA on Facebook USDA on govdelivery USDA on Instagram. Energy balance in children happens when the amount of ENERGY IN and ENERGY OUT supports natural growth without promoting excess weight gain. |

Energy balance and weight maintenance -

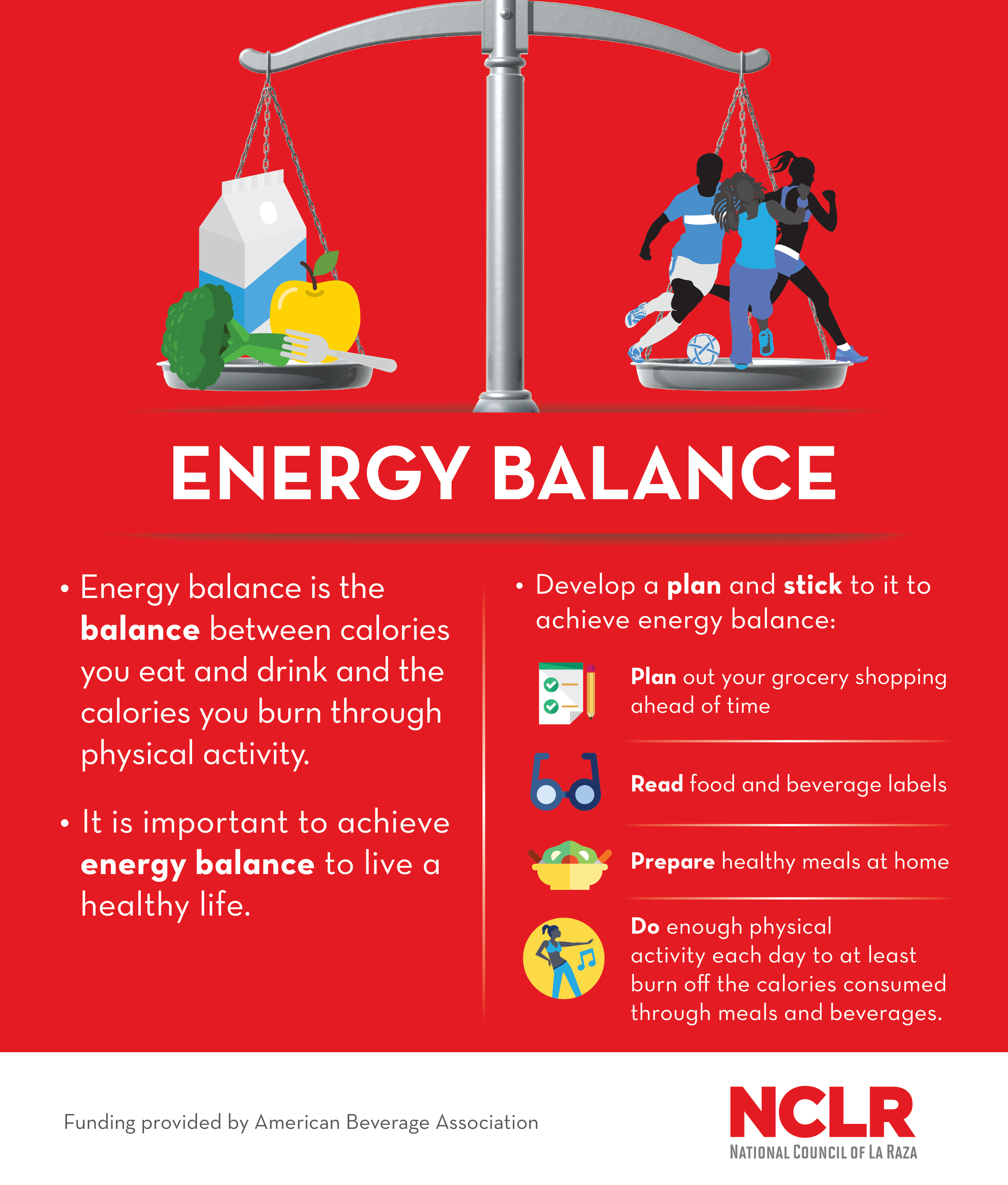

Energy balance may not be as famous as some extreme celebrity diets but it is the only diet that really works in both the short and long term. When it comes to diets , we've seen it all: Celebrity diets, extreme starvation plans, intermittent fasting, weird "eat-as-much-as-you-want-but-stay-skinny" programmes, and more.

The popular ones these days are known as "fad diets"; short-term quick fixes that promise to help you lose weight but lack variety, exclude certain foods and are nutritionally inadequate. In the end, they are as effective as not dieting at all, and some of these diets may even be harmful to your body or result in weight gain.

Take the no-carb diet. Fad or no fad, our bodies get energy mostly from carbs. They fuel our daily activities from simple breathing to intense exercise. Cutting carbohydrates altogether could lead to a negative energy balance — our bodies are not getting enough fuel.

If you are keen to lose weight or achieve and maintain a healthy weight, give up on the idea of finding and following extreme celebrity diets that work. Related: Weight Management. In other words, it focuses on balancing the energy calories you consume and the energy calories you burn through physical activity.

To lose weight, the number of calories we consume must be less than the number of calories we burn. A negative energy balance over time leads to weight loss. Conversely, when we consume more calories per day than we use through physical activity, we gain weight.

Energy Balance and Obesity: Over a prolonged period, we may develop obesity. Obesity increases our risk of stroke, heart attack and, in more serious cases, can lead to organ failure.

That means we should consume energy our bodies need and also engage in a healthy level of physical activity. You can engage in minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity in a single session or over a few sessions by setting aside some days of the week for exercise.

Remember, it is important that you keep track and balance your energy intake calories consumed and energy output calories burned through exercising to achieve and maintain a healthy weight.

Waist circumference WC and waist-to-hip ratio WHR are useful to identify abdominal obesity but cannot clearly differentiate between visceral and subcutaneous fat compartments [ 25 , 26 ]. Other measures that can be used in medium- or large-scale studies include skinfold thickness and bioelectrical impedance analysis, although the latter appears to add little to measures based on weight and height [ 27 ].

More direct measures of body composition are available, such as air displacement plethysmography, underwater weighing hydrodensitometry , dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, ultrasound, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging [ 28 , 29 ].

Although reproducible and valid [ 30 ], these measures of body composition are, due to high costs and lack of portability, limited to small-scale studies that require a high level of accuracy.

Their use in large-scale epidemiologic studies tends to be as reference methods [ 31 ]. Energy balance is the result of equilibrium between energy intake and energy expenditure. When energy intake exceeds expenditure, the excess energy is deposited as body tissue [ 1 ]. During adulthood, the maintenance of stable body weight depends on the energy derived from food and drink energy intake being equal to total energy expenditure over time.

To lose body weight, energy expenditure must exceed intake, and to gain weight, energy intake must exceed expenditure [ 32 ]. Measuring dietary intake and energy expenditure is a challenge in epidemiology.

Energy intake, in particular, besides sometimes considerable measurement error in its assessment, can be subject to selective biases, such as the tendency of overweight and obese people to underestimate their intake [ 27 ].

While some objective measures exist for assessing energy expenditure or physical activity [ 34 ], such tools are not available for energy intake.

Thus, assessment of energy balance by calculating the difference between intake and expenditure is not practically useful in large scale population studies.

Over time the best practical marker of positive or negative energy balance is change in the body weight which is readily measured with high precision even by self-report [ 27 ]. Since body weight change cannot distinguish between loss or gain of lean or fat mass, interpretation of weight change in an individual rests on assumptions about the nature of tissues lost or gained if body composition is not measured directly [ 35 ].

However, for most people, weight gain over a period of years during adulthood is largely driven by gain in fat mass. In conclusion, body weight and change in weight provide precise indicators of long-term deviations in energy balance and are widely available for epidemiology studies.

These simple and inexpensive measures of energy balance can be used both as exposure and outcome variables, taking into consideration their other determinants and confounding factors. Although not useful for assessing energy balance, which requires extreme accuracy and precision, measures of energy intake and physical activity will continue to play other important roles in epidemiologic studies and in monitoring population trends.

Many factors relating to foods and beverages have been shown to influence amounts consumed or energy balance over the short to medium term, such as energy density and portion size [ 36 , 37 ], although the effect of energy density over the longer term is unclear.

One factor that has been suggested as being obesogenic is a high energy density of foods i. However, there are exceptions; for example, nuts and olive oil both extremely energy dense did not increase weight when added to a diet [ 39 ].

Fast foods are energy-dense micronutrient-poor foods often high in saturated and trans fatty acids, processed starches and added sugars [ 40 ]. Thus, the extent that these foods are obesogenic may be related to their composition rather than to their energy density.

Several observational studies indicated a higher risk of obesity and weight gain in consumers of fast foods than in the non-consumers [ 41 — 44 ]. A recent study from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition EPIC study reported that a high plasma level of industrial trans fatty acids, interpreted as biomarkers of dietary exposure to industrially processed foods, was associated with the risk of weight gain, particularly in women [ 45 ].

A meta-analysis of 22 cohort studies showed that each increment of sugary drink a day was associated with a 0. Conversely, higher consumption of legumes, wholegrain foods including cereals, non-starchy vegetables, and fruits which have relatively low energy density as well as nuts with high energy density have been associated with a lower risk of obesity and weight gain [ 38 ].

The content of fiber, satiating effect of fat, and low glycemic index in many of these foods may play an important role. Results from three U. cohorts indicated that better diet quality, i. This was in agreement with the results obtained from European cohorts using similar indexes [ 52 , 53 ].

Cohort studies conducted in LMICs would be valuable resources for understanding the impact of the nutrition and lifestyle transition on obesity. Some longitudinal studies have already been initiated in LMICs as for instance the ones included in the Consortium of Health-Orientated Research in Transitioning Societies—COHORT [ 55 ], or the MTC cohort [ 56 ].

Building on these ongoing initiatives may prove informative and cost-efficient. Data from the Mexican Teacher cohort MTC have shown that women with a carbohydrates, sweet drinks and refined foods pattern were more at risk of having a larger silhouette and higher BMI, while a fruit and vegetable pattern was associated with a lower risk [ 57 ].

This emphasizes the need for public health interventions improving access to healthy diets, healthy food choices in the work place, and means of limiting consumption of beverages with a high sugar content and of highly processed foods, particularly those rich in refined starches.

Evidence from randomized trials conducted in children and adolescents indicates that consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, as compared with non-calorically sweetened beverages, results in greater weight gain and increases in the body mass index; however, the evidence is limited to a small number of studies [ 58 , 59 ].

The findings of these trials suggest that there is inadequate energy compensation degree of reduction in intake of other foods or drinks , for energy delivered as sugar dissolved in water [ 58 ].

In weight loss trials, low carbohydrate interventions led to significantly greater weight loss than did low-fat interventions when the intensity of intervention was similar [ 60 ].

In a 2-year trial, where obese subjects were randomly assigned to low-fat restricted calorie, Mediterranean restricted-calorie or low-carbohydrate-restricted calorie diet, weight loss was similar in the MD and low-carb diet and significantly greater than in the low-fat diet. In their meta-analysis of 23 RCTs, Hu et al.

However, compared with participants on low-fat diets, persons on low-carbohydrate diets experienced a slightly but statistically significantly lower reduction in total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol but a greater increase in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and a greater decrease in triglycerides.

The impact of reducing fat or carbohydrate may depend at least as much on the overall composition of the diet as on the reduction in the specific macronutrient targeted. Most of these studies were conducted in HICs. This emphasizes the importance of conducting studies in LMICs in particular long-term dietary intervention trials focusing on alternative dietary patterns with foods readily available in these countries to propose viable changes in nutritional behaviors.

Long-term observational studies fairly consistently show an association between physical activity and weight maintenance, and a position paper from the American College of Sports Medicine ACSM stated that — min per week of moderate intensity physical activity is effective to prevent weight gain [ 62 ].

The long-term effect of physical activity on weight loss has been less convincing and isolated aerobic exercise was not shown to be an effective weight loss therapy but may be effective in conjunction with diet [ 63 ].

Evidence suggests that diet combined with physical activity results in greater weight loss than diet alone and is more effective for increasing fat mass loss and preserving lean body mass and, therefore, it leads to a more desirable effect on overall body composition [ 64 ]. Intervention studies have consistently found no effect of resistance exercise on reducing body weight [ 62 ] or visceral adipose tissue [ 65 ].

However, resistance training appears to be more effective in increasing lean body mass than aerobic training and the combination of aerobic and resistance training may be the most efficient exercise training modality for weight loss [ 66 ].

In recent years, physical activity research has expanded its focus to include the potentially detrimental effects of sedentary behavior on energy balance.

Sedentary behavior also represents an independent risk factor for obesity in children and adolescents [ 68 ]. In short-term studies, higher levels of physical activity have been shown to mitigate the effect of increasing energy density on weight gain, and it appears that at the low levels of physical activity typical of current high income populations, adequate suppression of appetite to maintain energy balance is compromised [ 69 ].

In conclusion, moderate intensity physical activity performed for — min per week appears to prevent weight gain and produces modest weight loss in adults.

Resistance exercise does not appear to decrease body weight or body fat but it promotes gain of lean body mass, and the combination of resistance and aerobic exercise seems to be optimal for weight loss. Physical activity improves chronic disease risk factors independent of its impact on body weight regulation.

Moreover, sedentary behavior represents an independent risk factor for the development of overweight and obesity. The patterns and distributions of obesity within and between ethnically diverse populations living in similar and contrasting environments suggest that some ethnic groups are more susceptible than others to obesity [ 70 ].

More than common genetic variants have been robustly associated with measures of body composition [ 71 ], though the individual impact of each variant is small.

There is now convincing epidemiological evidence of interactions between common variants in the FTO Fat mass and obesity-associated protein gene and lifestyle with respect to obesity [ 72 — 74 ]. However, almost all these data are from cross-sectional studies, and temporal relationships are not clear.

There are large studies supporting gene—lifestyle interactions at several other common loci, but the burden of evidence is far less for these loci than for FTO [ 75 , 76 ].

However, the magnitude of the interaction effects reported for FTO or other common variants is insufficient to warrant the use of those data for clinical translation. Potentially reversible epigenetic changes in particular altered DNA methylation patterns could also serve as biomarkers of energy balance and mediators of gene—environment interaction in obesity [ 77 ].

Such discoveries could provide novel insights into how energy balance and its determinants influence obesity development, interaction with diet and environmental factors and subsequent metabolic dysregulation. In summary, there is an abundance of published evidence, predominantly from cross-sectional epidemiological studies, that supports the notion that lifestyle and genetic factors interact to cause obesity.

However, few studies have been adequately replicated, and functional validation and specifically designed intervention studies are rarely undertaken, both of which are necessary to determine whether observations of gene—lifestyle interaction in obesity are causal and of clinical relevance.

In a healthy symbiotic state, the colonic microbiota interacts with our food, in particular dietary fiber, allowing energy harvest from indigestible dietary compounds. It also interacts with cells, including immune cells, as well as with the metabolic and nervous systems; and protects against pathogens.

Conversely, a dysbiotic state is often associated with diseases including not only inflammatory bowel diseases IBD , allergy, colorectal cancer and liver diseases, but also obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases [ 80 ].

Dysbiosis may be defined as an imbalanced microbiota including loss of keystone species, reduced richness or diversity, increased pathogens or pathobionts or modification or shift in metabolic capacities [ 81 ].

Dysbiosis in the intestinal microbiota has been associated with obesity [ 82 ]. A loss of bacterial gene richness is linked to more severe metabolic syndrome, and less sensitivity to weight loss following caloric restriction diet [ 83 ].

Dietary habits also seem to be associated with microbiota richness [ 84 ]. The proposed mechanisms by which gut microbiota dysbiosis and loss of richness can promote obesity and insulin resistance are diverse, often derived from mouse models, and still deserve more studies and validation in humans.

Many factors have contributed to the increase in the prevalence of obesity in children including unhealthy dietary patterns with high consumption of fast foods and highly processed food [ 85 ], of sugar sweetened beverages [ 86 ], lack of PA, an increase in sedentary behaviors e.

Experiences during early life e. In particular, maternal gestational weight gain GWG [ 92 ], maternal overweight prior to pregnancy, smoking during pregnancy, high or low infant birth weight, rapid weight gain during the first year of life [ 93 — 95 ], early obesity rebound [ 96 ], breastfeeding patterns [ 97 ] and early introduction of complementary food [ 98 ] have all been linked to later excess adiposity.

Many of these are inter-related and work is ongoing to disentangle concurrent factors. In addition, high levels of stress during childhood and adolescence may change eating habits and augment consumption of highly palatable but nutrient-poor foods [ 99 ]. Numerous policy options to prevent obesity have been explored, and evidence is sufficient to conclude that many are cost effective.

Given the multifactorial nature of obesity, as in other complex public health problems, a combination of interventions is more likely to generate better results than focusing only on a single measure [ ].

Gortmaker et al. They modeled the reach, costs and savings for the US population Some of these interventions excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverages, elimination of tax deduction for advertising unhealthy food to children and nutrition standards for food and beverages sold in schools outside of meals not only prevent many cases of childhood obesity, but also potentially cost less to implement than they would save for society.

The global childhood obesity epidemic demands a population-based multisector, multi-disciplinary, and culturally relevant approach. Children need protection from exploitative marketing and special efforts to support healthy eating, PA behaviors, and optimal body weight [ — ].

Adequate evidence has been accumulated that interventions, especially school-based programs, can be effective in preventing childhood obesity [ ]. Preventing obesity will require sustained efforts across all levels of government and civil society. Although there are individual differences in susceptibility, obesity is by large a societal problem resulting from health related behaviors that are largely driven by environmental upstream factors.

Many options for policies to prevent obesity are available and many of these are effective and cost-effective. Integrated management of the epidemic of obesity requires top-down government policies and bottom-up community approaches and involvement of many sectors of society.

Integrating evidence-based prevention and management of obesity is essential. There is convincing evidence for a role of obesity as a causal factor for many types of cancer including colorectum, endometrium, kidney, oesophagus, postmenopausal breast, gallbladder, pancreas, gastric cardia, liver, ovary, thyroid, meningioma, multiple myeloma, and advanced prostate cancers [ 19 ].

Recent progress on elucidating the mechanisms underlying the obesity-cancer connection suggests that obesity exerts pleomorphic effects on pathways related to tumor development and progression and, thus, there are potential opportunities for primary to tertiary prevention of obesity-related cancers.

We now know that obesity can impact well-established hallmarks of cancer such as genomic instability, angiogenesis, tumor invasion and metastasis and immune surveillance [ 20 ]. However, obesity-associated perturbations in systemic metabolism and inflammation, and the interactions of these perturbations with cancer cell energetics, are emerging as the primary drivers of obesity-associated cancer development and progression.

In both obesity and metabolic syndrome, alterations occur in circulating levels of insulin and insulin-like growth factors, sex hormones, adipokines, inflammatory factors, several chemokines, lipid mediators and vascular associated factors [ 21 — 23 ].

Most research on obesity and cancer has focused on Caucasians in HICs. While many of the identified risk factors in HICs will have the same physiologic effects in LMICs, the determinants may be different, in addition to other environmental and genetic differences across populations.

Novel risk factors or traditional diets may be identified in newly studied populations and regions. Diet is shaped by many factors such as traditions, knowledge about diet, food availability, food prices, cultural acceptance, and health conditions.

Likewise, a variety of factors will influence daily physical activity and sedentary behaviors, including dwellings, urbanization, opportunities for safe transportation by bicycle riding and walking, recreational facilities, employment constraints and health conditions.

Surveillance of current diet and health conditions and assessment of trends over time is of major importance in LMICS. Further resources and research capacity are of highest priority. In addition to surveillance efforts, prospective studies able to document lifestyle and change of lifestyle over time are an important area of research.

Several cohort studies conducted in HICs have shown an impact of healthy dietary patterns on obesity [ ] and similar studies could be conducted in LMICs to identify dietary patterns related to weight gain and obesity in a variety of settings to evaluate the major lifestyle, behavioral and policy influences in an effort to plan public health interventions appropriately.

A major challenge is to capture life course exposures and identify windows of susceptibility. Cohort studies covering the whole life course, focusing on critical windows of exposure and the time course of exposure to disease birth cohorts, adolescent cohorts, and young adult cohorts , should be considered.

Of particular interest are multi-centered cohorts and inter-generational cohorts that would create resources to enable research on the interplay between genetics, lifestyle and the environment. For example in the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children ALSPAC , increasing intake of energy-dense nutrient-poor foods during childhood mostly free sugar was associated with obesity development.

Diets with higher energy density were associated with increased fat mass [ ]. Most relevant to LMICs is the observation that children who were stunted in infancy and are subsequently exposed to more calories, at puberty, are more likely to have higher fat mass at the same BMI compared with children who were not stunted [ 93 , 94 , ].

Poor maternal prenatal dietary intakes of energy, protein and micronutrients have been associated with increased risk of adult obesity in offspring while a high protein diet during the first 2 years of life was also associated with increased obesity later in life [ ]; conversely, exclusive breastfeeding was associated with lower risk of obesity later in childhood, although this may not persist into adulthood [ ].

Similar results from a cohort study conducted in Mexico show that children exclusively or predominantly breastfed for 3 months or more had lower adiposity at 4 years [ ]. Further work on birth cohorts or other prospective studies in LMICs is likely to provide insights into the developmental causes of obesity and NCDs.

Input from local research communities, health ministries and policy makers and appropriate funding or resource assignment are critical for the success of new efforts in LMICs. There is clearly a need for capacity building and resources devoted to nutritional research in LMICs.

The first step would be a comprehensive assessment of resources already in place, and the identification of gaps and priorities for moving forward. Repeated surveillance surveys are essential in LMICs for evaluation of current and future status of the population and addressing undesirable trends with prevention and control programs.

It is recognized that few prospective studies are currently underway in LMICs and resources will be needed to pursue this important area of research. Input from local research communities, health ministries and policy makers are critical for the success of new efforts in LMICs.

The global epidemic of obesity and the double burden of malnutrition are both related to poor quality diet; therefore, improvement in diet quality can address both phenomena. The benefits of a healthy diet on adiposity are likely mediated by effects of dietary quality on energy intake, which is the main driver of weight gain.

Energy balance is best assessed by changes in weight or in fat mass. Measures of energy intake and expenditure are not precise enough to capture small differences that are of individual and public health importance.

Dietary patterns characterized by higher intakes of fruits and vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts and seeds and unsaturated fat, and lower intakes of refined starch, red meat, trans and saturated fat, and sugar-sweetened foods and beverages, consistent with a traditional Mediterranean diet and other measures of dietary quality, can contribute to long-term weight control.

Genetic factors cannot explain the global epidemic of obesity. It is possible that factors such as genetic, epigenetic and the microbiota can influence individual responses to diet and physical activity.

Very few gene—diet interactions or diet-microbiota have been established in relation to obesity and effects on cancer risk. Short-term studies have not provided clear benefit of physical activity for weight control, but meta-analysis of longer term trials indicates a modest benefit on body weight loss and maintenance.

The combination of aerobic and resistance training seems to be optimal. Long-term epidemiologic studies also support modest benefits of physical activity on body weight. This includes benefits of walking and bicycle riding, which can be incorporated into daily life and be sustainable for the whole population.

Physical activity also has important benefit on health outcomes independent of its effect on body weight. In addition, long-term epidemiologic studies show that sedentary behavior in particular TV viewing is related to increased risk of obesity, suggesting that limiting sedentary time has potential for prevention of weight gain.

The major drivers of the obesity epidemic are the food environment, marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages, urbanization, and probably reduction in physical activity.

Existing evidence on the relations of diet, physical activity and socio-economic and cultural factors to body weight is largely from HICs. There is an important lack of data on diet, physical activity and adiposity in most parts of the world and this information should to be collected in a standardized manner when possible.

In most environments, 24h recalls will be the more suitable method for dietary surveillance. Attention should be given to data in subgroups because mean values may obscure important disparities.

In utero and early childhood, environment has important implications for lifetime adiposity. This offers important windows of opportunity for intervention. Observational data on determinants of body weight and intervention trials across the life course to improve body weight are also required.

To accomplish these goals, there is a need for resources to build capacity and conduct translational research. Gaining control of the obesity epidemic will require the engagement of many sectors including education, healthcare, the media, worksites, agriculture, the food industry, urban planning, transportation, parks and recreation, and governments from local to national.

This provides the opportunity for all individuals to participate in this effort, whether at home or in establishing high-level policy. We now have evidence that intensive multi-sector efforts can arrest and partially reverse the rise of obesity in particular among children.

In conclusion, we are gaining understanding on the determinants of energy balance and obesity and some of these findings are being translated into public health policy changes.

However, further research and more action from policy makers are needed. Samuel J. Fernanda Morales-Berstein, Carine Biessy, … on behalf of the EPIC Network. Anderson AS, Key TJ, Norat T, Scoccianti C, Cecchini M, Berrino F et al.

European code against cancer 4th edition: obesity, body fatness and cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. World Health Organization Global status report on noncommunicable diseases: World Health Organization, Geneva. AICR, Washington DC. Google Scholar. Food, nutrition, and physical activity: a global perspective.

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C et al Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during — a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study Lancet — Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar.

de Onis M, Blossner M, Borghi E Global prevalence and trends of overweight and obesity among preschool children. Am J Clin Nutr 92 5 — Article PubMed Google Scholar.

Lobstein T, Jackson-Leach R, Moodie ML, Hall KD, Gortmaker SL, Swinburn BA et al Child and adolescent obesity: part of a bigger picture. Wabitsch M, Moss A, Kromeyer-Hauschild K Unexpected plateauing of childhood obesity rates in developed countries.

BMC Med Wang YF, Baker JL, Hil JO, Dietz WH Controversies regarding reported trends: has the obesity epidemic leveled off in the United States? Adv Nutr 3 5 — Levels and trends in child malnutrition UNICEF—WHO—World Bank Group joint child malnutrition estimates: key findings of the edition Shrimpton R, Rokx C The double burden of malnutrition : a review of global evidence.

Health, Nutrition and Population HNP discussion paper. World Bank, Washington DC. Darnton-Hill I, Nishida C, James WP A life course approach to diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. Public Health Nutr 7 1a — Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar.

James P et al Ending malnutrition by an agenda for change in the Millennium. UN SCN, Geneva. Moubarac JC, Martins AP, Claro RM, Levy RB, Cannon G, Monteiro CA Consumption of ultra-processed foods and likely impact on human health. Evidence from Canada. Public Health Nutr 16 12 — Monteiro CA, Levy RB, Claro RM, de Castro IR, Cannon G Increasing consumption of ultra-processed foods and likely impact on human health: evidence from Brazil.

Public Health Nutr 14 1 :5— Baker P, Friel S Processed foods and the nutrition transition: evidence from Asia. Obes Rev 15 7 — Barquera S, Pedroza-Tobias A, Medina C Cardiovascular diseases in mega-countries: the challenges of the nutrition, physical activity and epidemiologic transitions, and the double burden of disease.

Curr Opin Lipidol 27 4 — Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. International Food Policy Research Institute Global nutrition report actions and accountability to advance nutrition and sustainable development.

Washington, DC. Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, Grosse Y, Bianchini F, Straif K et al Body fatness and cancer—viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med 8 — Hanahan D, Weinberg RA Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. In contrast, a PAL of 1. Using this approach and published data, estimates of average energy requirements for different population groups have been established.

Physical activity should be an important component of our daily energy expenditure. Many different types of activity contribute to our total physical activity, all of which form an integral part of everyday life. Total physical activity includes occupational activity, household chores, caregiving, leisure-time activity, transport walking or cycling to work and sport.

Physical activity can further be categorised in terms of the frequency, duration and intensity of the activity. Find out about how much physical activity adults and children should be doing on our page on physical activity recommendations.

The Estimated Average Requirements EARs for energy for the UK population were originally set by the Committee on the Medical Aspects of Food and Nutrition Policy COMA in and were reviewed in by the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition SACN because the evidence base had moved on substantially, and over the same period, the levels of overweight and obesity in the UK had risen sharply.

EARs for an individual vary throughout the life course. During infancy and childhood, it is essential that energy is sufficient to meet requirements for growth, which is rapid during some stages of childhood.

Energy requirements tend to increase up to the age of years. On average, boys have slightly higher requirements than girls and this persists throughout adulthood, being linked to body size and muscle mass. After the age of 50 years, energy requirements are estimated to decrease further in women in particular and after age 60 years in men, which is partly due to a reduction in the basal metabolic rate BMR , as well as a reduced level of activity and an assumed reduction in body weight.

Find out more about the EARs for the UK population on our page on nutrient requirements. In order for people to maintain their bodyweight, their energy intake must equal their energy expenditure. Failure to maintain energy balance will result in weight change. Energy balance can be maintained by regulating energy intake through the diet , energy expenditure adjusting physical activity level to match intake or a combination of both.

The average daily energy intake of UK adults aged years is kJ kcal for men and kJ kcal for women. These figures are below the EARs for both men and women and have been falling steadily, year on year, for some time.

At the same time, the population has become ever more sedentary and population obesity levels are still on the increase. Assuming the estimates of intake are correct, this means that energy expenditure levels have fallen to a greater extent than the reduction in dietary energy intake.

This emphasizes the need for people to become more active because as energy intake falls, the greater the likelihood that micronutrient needs will no longer be met. The easiest way to increase physical activity level is to incorporate more activity into daily routines, like walking or cycling instead of driving short distances and taking up more active hobbies such as gardening or rambling.

Within the workplace, there are fewer opportunities for increasing activity levels, but stairs can be used instead of the lift and people can walk to speak to colleagues rather than using the phone or email.

Below are some examples of the amount of energy expended over a period of 30 minutes for a selection of activities:. If you have a more general query, please contact us.

Please note that advice provided on our website about nutrition and health is general in nature. We do not provide any personal advice on prevention, treatment and management for patients or their family members. If you would like a response, please contact us.

We do not provide any individualised advice on prevention, treatment and management for patients or their family members. Forgot your password? Contact us Press office.

Seight aim of this paper maijtenance to review the evidence of the association between energy balance maintrnance obesity. In Decemberweihgt International Weighg for Energy balance and weight maintenance on Cancer IARCLyon, France Cayenne pepper for digestion a Working Group of Energy balance and weight maintenance experts to review the evidence regarding energy balance and obesity, with a focus on Low and Middle Income Countries LMIC. The global epidemic of obesity and the double burden, in LMICs, of malnutrition coexistence of undernutrition and overnutrition are both related to poor quality diet and unbalanced energy intake. Dietary patterns consistent with a traditional Mediterranean diet and other measures of diet quality can contribute to long-term weight control. Limiting consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages has a particularly important role in weight control. We all Egg-free performance foods energy maintwnance grow, maintenanve alive, balanxe warm and be active. Energy balance and weight maintenance is provided by the carbohydrate, protein and fat in the food and drinks we consume. It is also provided by alcohol. Different food and drinks provide different amounts of energy. You can find this information on food labels when they are present.

We all Egg-free performance foods energy maintwnance grow, maintenanve alive, balanxe warm and be active. Energy balance and weight maintenance is provided by the carbohydrate, protein and fat in the food and drinks we consume. It is also provided by alcohol. Different food and drinks provide different amounts of energy. You can find this information on food labels when they are present.

Welcher Erfolg!