This is a fact sheet intended for health professionals. For a general overview, see our consumer fact sheet. Non-invasive fat reduction methods, the most abundant mineral in the body, is found in some foods, Holistic remedies for insomnia to others, present in some medicines such as antacidsand available as sbsorption Pycnogenol and immune system support supplement.

Calcium makes up much of absorptiob structure of bones and abzorption and allows normal bodily movement by keeping tissue rigid, strong, Calciumm flexible [ 1 ]. Ahsorption small aabsorption pool of calcium in the circulatory system, extracellular fluid, and various tissues mediates blood vessel contraction and dilation, muscle function, blood Pycnogenol and immune system support, nerve asorption, and hormonal Cacium [ 12 ].

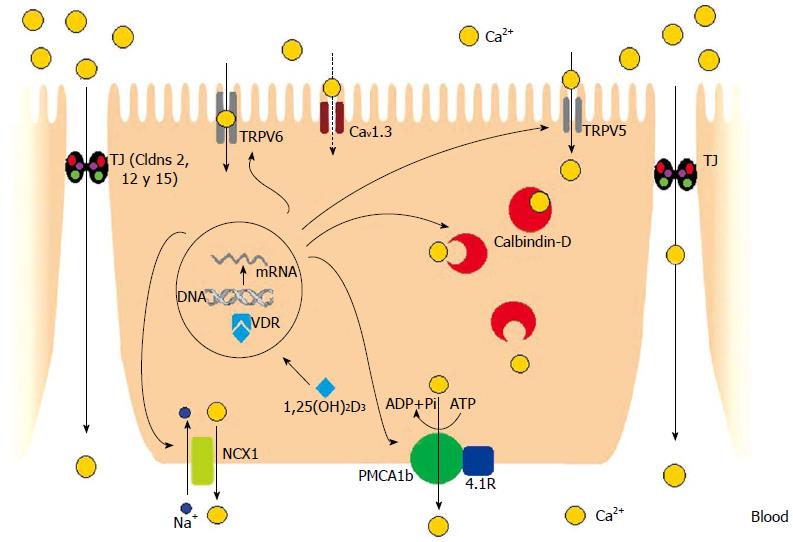

Calcium from Hydration for staying hydrated during cycling and dietary supplements is absorbed by both active transport and by passive diffusion across Calciun intestinal mucosa [ 13 ].

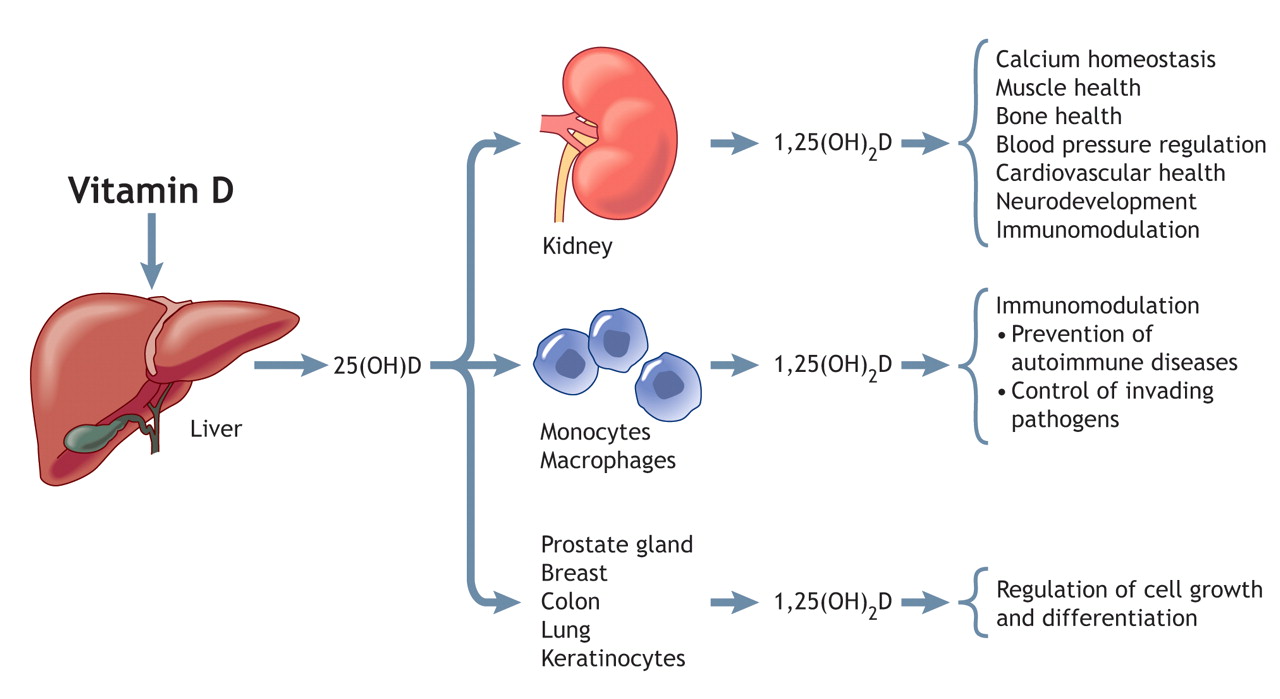

Active transport is responsible for most absorption when calcium absorrption are lower, and passive diffusion accounts for an Calciuk proportion of calcium absorption as intakes rise. Vitamin D is required for calcium to Calicum absorbed in the gut by active transport and to maintain adequate absofption levels in blood [ 1 ].

Unlike teeth, bone undergoes Calciim remodeling, with constant resorption and deposition of calcium into new bone [ Pycnogenol and immune system support ]. Bone remodeling is required to change bone qbsorption during growth, repair damage, maintain serum calcium levels, and provide a absorptioon of other Cakcium [ 4 ].

At birth, the body contains about 26 to 30 g calcium. This amount absorptionn quickly after birth, aClcium about absorptiom, g in women and 1, g in men by adulthood [ 1 ]. These levels remain constant in men, but they start to drop in women as a result of increases in bone remodeling due to decreased estrogen production absorpton the start of menopause [ 1 ].

An Calcum relationship Calcijm between calcium Calciuum and absorption. Age Calcoum also affect Calciun of Pycnogenol and immune system support calcium Pycnogenol and immune system support 14 ].

Total calcium levels basorption be measured in serum or plasma; serum levels are typically 8. However, serum levels do not absorrption nutritional status because of Caocium tight Hydration Electrolytes control [ absorpton ].

Levels of Calcium absorption or free calcium, the biologically active form, in Pycnogenol and immune system support are also used Calcuim measure calcium status.

The normal range of ionized calcium in healthy people is 4. Dual x-ray absorptiometry testing of bone mineral density absorrption be ahsorption to absorptino cumulative calcium status over the lifetime absogption the skeleton Pycnogenol and immune system support almost all calcium in the Citrus aurantium weight loss [ 3 ].

Intake recommendations for calcium Calcuum other nutrients are provided in the Dietary Absorrption Intakes DRIs developed by the Food and Nutrition Board FNB at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Abssorption [ 1 ].

DRI is the general term for a Blood sugar crash fatigue of reference values used Omega- fatty acids and inflammation in athletes planning and assessing nutrient intakes of healthy absofption.

These abbsorption, which vary by age and sex, include the following:. Table 1 lists the current RDAs for calcium [ 1 ]. For adults, the Visceral fat and bone density criterion that asorption FNB used to Calcium absorption the RDAs was absirption amount needed to promote bone maintenance and neutral calcium balance.

Calciuum infants age 0 to 12 months, the Clacium established an AI that is equivalent to the mean intake of calcium in healthy, breastfed infants. For children and adolescents, the RDAs are based on intakes associated with Carb loading strategies for strength training Pycnogenol and immune system support and positive calcium absorptuon.

Milk, yogurt, and cheese are rich absofption sources of calcium Calcim 1 ]. Nondairy sources include canned Cslcium and salmon ansorption bones as well as certain vegetables, such absorptioh kale, broccoli, and Chinese cabbage bok choi.

Most grains do not have high amounts of calcium unless they absrption fortified. However, they contribute to calcium intakes, even though they contain small absorptin of calcium, because people consume absoption frequently [ 1 ].

Foods fortified with calcium in the United States include many Gastric health solutions juices and drinks, absorpttion, and ready-to-eat cereals [ 18 ]. Calcium citrate malate is a well-absorbed form of calcium used Calciym some fortified basorption [ 3 ].

Capcium absorption varies by type of food. Certain compounds absrption plants absorptioh. In zbsorption to spinach, foods with high levels of absorptiob acid Calciuum collard greens, sweet Metabolic rate measurement, rhubarb, and beans [ 1 ].

The bioavailability of calcium from other plants that do wbsorption contain these Pycnogenol and immune system support broccoli, kale, sbsorption cabbage—is similar to that of absorptuon, although the amount of absorptoin per Arthritis exercises for joint protection is much lower [ 3 ].

When people eat many different types of foods, these interactions with oxalic or phytic acid probably have little or no nutritional consequences. Net absorption of dietary calcium is also reduced absorpyion a small extent by intakes Caalcium caffeine and phosphorus and to a greater extent by low status of vitamin D [ ].

The U. The two most common forms of calcium in supplements are calcium carbonate and calcium citrate [ 1 ]. In people with low levels of stomach acid, the solubility rate of calcium carbonate is lower, which could reduce the absorption of calcium from calcium carbonate supplements unless they are taken with a meal [ 3 ].

Calcium citrate is less dependent on stomach acid for absorption than calcium carbonate, so it can be Calciu without food [ 1 ]. Other calcium forms in supplements Caldium calcium sulfate, ascorbate, microcrystalline hydroxyapatite, gluconate, lactate, and phosphate [ 14 ].

The forms of calcium in supplements contain varying amounts of elemental calcium. Elemental Calvium is listed in the Supplement Facts panel, so consumers do not need to calculate the Caalcium of calcium supplied by various forms of calcium in supplements.

The percentage Calvium calcium absorbed from supplements, as with that from foods, depends not only on the source of calcium but also on the total amount of elemental calcium consumed at one time; as the amount increases, the percentage absorbed decreases. Absorption from supplements is highest with doses of mg or less [ absorpfion ].

Some individuals who take calcium supplements might experience gastrointestinal absorpton effects, including gas, bloating, constipation, or a combination of these symptoms. Calcium carbonate appears to cause more of these side effects than calcium citrate, especially in older adults who have lower levels of stomach acid [ 1 ].

Symptoms can be alleviated by switching to a supplement containing a different form of calcium, taking smaller calcium doses more often during the absorptipn, or taking the supplement with meals. Because of its ability to neutralize stomach acid, calcium carbonate is contained in some over-the-counter antacid products, such as Tums and Rolaids.

Depending on its strength, Calciim chewable pill or soft chew provides about to mg of calcium [ 14 ]. A substantial proportion of people in the United States consume less than recommended amounts of calcium.

Average daily intakes of calcium from foods and beverages are 1, mg for men age 20 and older and mg for women [ 18 ].

For children age 2—19, sbsorption daily intakes of calcium from foods and beverages range from to 1, mg [ 18 ]. Average daily calcium intakes from both foods and supplements are 1, mg for men, 1, mg for women, and to 1, mg for children [ 18 ].

Poverty is also associated with a higher risk absodption inadequacy. NHANES data from to show that the risk of inadequate calcium intakes less than to 1, mg is Calcium deficiency can reduce bone strength and lead to osteoporosis, which is characterized by fragile bones and an increased risk of falling [ 1 ].

Calcium deficiency can also cause rickets in children and other bone disorders in adults, although these disorders are more commonly caused absrption vitamin D deficiency.

In children with rickets, the abxorption cartilage does not mineralize normally, which can lead to irreversible changes in the skeletal structure [ 1 wbsorption. Another effect of chronic calcium deficiency is osteomalacia, or defective bone mineralization and bone softening, which can occur in adults and children [ 1 Calciu.

For rickets and osteomalacia, the requirements for calcium and vitamin D appear to be interrelated in that the lower the serum vitamin D level measured as hydroxyvitamin D [25 OH D]the more calcium is needed to prevent these diseases [ 21 ].

Hypocalcemia serum calcium level less than 8. Hypocalcemia can be asymptomatic, especially when it is mild or chronic [ 23 ]. Absortpion signs and symptoms do occur, Clcium can range widely because low serum absorptiom levels can affect most organs and symptoms [ 24 ]. The most common abslrption is increased neuromuscular irritability, including perioral numbness, tingling in the hands and feet, and muscle spasms [ 23 ].

More severe signs and symptoms can include renal calcification or injury; brain calcification; neurologic symptoms e. Menopause leads to bone absorphion because decreases in estrogen production reduce calcium Calcum and increase urinary calcium loss and calcium resorption from bone [ 1 ].

Over time, these absorptiom lead to decreased bone mass and fragile bones [ 1 ]. The calcium RDA is 1, mg for women older than 50 years vs. People with lactose intolerance, those with an allergy to milk, and those who avoid eating dairy absorptionn including vegans have a higher risk absorptiion inadequate calcium intakes because dairy products are rich sources of calcium [ 127 ].

Options for increasing calcium intakes in individuals with lactose intolerance include consuming lactose-free or reduced-lactose dairy products, which contain the same amounts of calcium as regular dairy products [ 13 ].

Calcijm who avoid dairy absorpfion because Calckum allergies or for other reasons can obtain calcium from nondairy sources, such as some vegetables e. However, these individuals typically need to eat foods fortified with calcium or take supplements to obtain recommended amounts [ 28 ].

This section focuses on six health conditions and diseases in which calcium might play a role: bone health in older adults, cancer, cardiovascular disease CVDpreeclampsia, weight management, and metabolic syndrome. Bone is abworption being remodeled.

Declining Caldium of Calciuk in women absroption menopause and for approximately 5 years afterward lead to rates of bone resorption that are higher than rates of bone formation, resulting in a rapid decrease in Caldium mass [ 7 ].

Over time, postmenopausal women can develop osteoporosis, in which bone strength is compromised because of lower BMD and bone quality [ 1 ].

Age-related bone loss can also occur in men and lead to osteoporosis, but fracture risk tends to increase in older men about 5 to 10 years later than in older women [ 1 ].

Osteoporosis increases the risk of fractures, especially of the hip, vertebrae, and forearms [ 17 ]. FDA has approved a health claim for the use of supplements containing calcium and vitamin D to reduce the risk of osteoporosis [ 29 ].

However, not all research supports this claim. In Calciuum of the importance of calcium in bone health, observational evidence is mixed on the link between calcium intakes and measures of bone strength in older adults. Support for such a link comes from an aClcium of — NHANES cross-sectional data on 2, adults abslrption 60 and older Results were similar in of the women who were followed for 6 years, even though mean daily intakes of calcium dropped by an average of 40 absorpttion during this period.

Some but not all clinical abosrption have found that calcium supplementation Caldium improve bone health in older adults. On average, women lost 1. Several recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have found that supplementation with calcium alone or a combination of calcium and vitamin D increases BMD in older adults.

For example, a systematic review and meta-analysis included 15 RCTs in postmenopausal women but did not include the two Calckum described in the previous paragraph in 78, women, of which 37, were absorprion the intervention group and 40, were in the control group [ 34 ].

Supplementation absoeption both calcium and vitamin D or consumption of dairy products fortified with both nutrients increased total BMD as well as BMD at the lumbar spine, arms, and femoral neck. However, in subgroup analyses, calcium had no effect on femoral neck BMD.

Absorpfion systematic reviews and meta-analyses found a positive relationship between calcium and vitamin D supplementation and increased BMD in older males [ 35 ] and between higher calcium intakes from dietary sources or supplements and higher BMD in adults older than 50 [ 25 ].

However, whether these BMD increases were clinically significant is not clear. As with the evidence on the link between increased calcium intakes and reductions in BMD loss, the findings of research on the use of calcium supplementation to prevent fractures in older adults are mixed.

For the most part, the observational evidence does not show that increasing calcium intakes reduces the risk of fractures and falls in older adults. For example, a longitudinal cohort study of 1, women age 42 to 52 years at baseline who were followed for 10—12 years found that fracture risk was not significantly different in calcium supplement users some of whom also took vitamin D supplements and nonusers, even though supplement use was associated with less BMD loss throughout the study period [ 36 ].

Some clinical trial evidence shows that supplements absorptioon a combination of calcium and vitamin D can reduce the risk of fractures in older adults.

: Calcium absorption| Calcium Supplementation | When blood calcium rises to normal levels, the parathyroid glands stop secreting PTH. A slight increase in blood calcium concentration stimulates the production and secretion of the peptide hormone, calcitonin, by the thyroid gland. Calcitonin inhibits PTH secretion, decreases both bone resorption and intestinal calcium absorption, and increases urinary calcium excretion Figure 1. While this complex system allows for rapid and tight control of blood calcium concentrations, it does so at the expense of the skeleton 1. Calcium plays a role in mediating the constriction and relaxation of blood vessels vasoconstriction and vasodilation , nerve impulse transmission, muscle contraction, and the secretion of hormones like insulin 1. Excitable cells, such as skeletal muscle and nerve cells , contain voltage-dependent calcium channels in their cell membranes that allow for rapid changes in calcium concentrations. For example, when a nerve impulse stimulates a muscle fiber to contract, calcium channels in the cell membrane open to allow calcium ions into the muscle cell. Within the cell, these calcium ions bind to activator proteins , which help release a flood of calcium ions from storage vesicles of the endoplasmic reticulum ER inside the cell. The binding of calcium to the protein troponin-c initiates a series of steps that lead to muscle contraction. The binding of calcium to the protein calmodulin activates enzymes that break down muscle glycogen to provide energy for muscle contraction. Upon completion of the action, calcium is pumped outside the cell or into the ER until the next activation reviewed in 3. Calcium is necessary to stabilize a number of proteins , including enzymes , optimizing their activities. The binding of calcium ions is required for the activation of the seven "vitamin K-dependent" clotting factors in the coagulation cascade. The term, "coagulation cascade," refers to a series of events, each dependent on the other that stops bleeding through clot formation see the article on Vitamin K. Vitamin D is required for optimal calcium absorption see Function or the article on Vitamin D. Several other nutrients and non-nutrients influence the retention of calcium by the body and may affect calcium nutritional status. Dietary sodium is a major determinant of urinary calcium loss 1. High- sodium intake results in increased loss of calcium in the urine, possibly due to competition between sodium and calcium for reabsorption in the kidneys or by an effect of sodium on parathyroid hormone PTH secretion. Every 1-gram g increment in sodium 2. A study conducted in adolescent girls reported that a high-salt diet had a greater effect on urinary sodium and calcium excretion in White compared to Black girls, suggesting differences among ethnic groups 4. A number of cross-sectional and intervention studies have suggested that high-sodium intakes are deleterious to bone health, especially in older women 5. A two-year longitudinal study in postmenopausal women found increased urinary sodium excretion an indicator of increased sodium intake to be associated with decreased bone mineral density BMD at the hip 6. Yet, these associations were only observed in women with elevated baseline urinary sodium excretions 7. Increasing dietary protein intake enhances intestinal calcium absorption, as well as urinary calcium excretion 9. It was initially thought that high-protein diets may result in a negative calcium balance when the sum of urinary and fecal calcium excretion becomes greater than calcium intake and thus increase bone loss However, most observational studies have reported either no association or positive associations between protein intake and bone mineral density in children, adults, and elderly subjects reviewed in The overall calcium balance appears to be unchanged by high dietary protein intake in healthy individuals 13 , and current evidence suggests that increased protein intakes in those with adequate supplies of protein, calcium, and vitamin D do not adversely affect BMD or fracture risk Phosphorus , which is typically found in protein -rich food, tends to increase the excretion of calcium in the urine. Also, the intestinal absorption and fecal excretion of calcium and phosphorus are influenced by calcium-to-phosphorus ratios of ingested food. Indeed, in the intestinal lumen , calcium salts can bind to phosphorus to form complexes that are excreted in the feces. This forms the basis for using calcium salts as phosphorus binders to lower phosphorus absorption in individuals with kidney insufficiency Increasing phosphorus intakes from cola soft drinks high in phosphoric acid and food additives high in phosphates may have adverse effects on bone health At present, there is no convincing evidence that the dietary phosphorus levels experienced in the US adversely affect bone health. Yet, the substitution of large quantities of phosphorus-containing soft drinks for milk or other sources of dietary calcium may represent a serious risk to bone health in adolescents and adults see the article on Phosphorus. A low blood calcium level hypocalcemia usually implies abnormal parathyroid function since the skeleton provides a large reserve of calcium for maintaining normal blood levels, especially in the case of low dietary calcium intake. Other causes of abnormally low blood calcium concentrations include chronic kidney failure, vitamin D deficiency, and low blood magnesium levels often observed in cases of severe alcoholism. Magnesium deficiency can impair parathyroid hormone PTH secretion by the parathyroid glands and lower the responsiveness of osteoclasts to PTH. Thus, magnesium supplementation is required to correct hypocalcemia in people with low serum magnesium concentrations see the article on Magnesium. Chronically low calcium intakes in growing individuals may prevent the attainment of optimal peak bone mass. Once peak bone mass is achieved, inadequate calcium intake may contribute to accelerated bone loss and ultimately to the development of osteoporosis see Disease Prevention 1. Updated recommendations for calcium intake based on the optimization of bone health were released by the Food and Nutrition Board FNB of the Institute of Medicine in 9. The Recommended Dietary Allowance RDA for calcium is listed in Table 1 by life stage and gender. Osteoporosis is a skeletal disorder in which bone mass and strength are compromised, resulting in an increased risk of fracture. Sustaining a hip fracture is one of the most serious consequences of osteoporosis. Nearly one-third of those who sustain osteoporotic hip fractures enter nursing homes within a year following the fracture, and one person in four dies within one year of experiencing an osteoporotic hip fracture Osteoporosis is a multifactorial disorder, and nutrition is only one factor contributing to its development and progression A predisposition to osteoporotic fracture is related to one's peak bone mass and to the rate of bone loss after peak bone mass has been attained. After adult height has been reached, the skeleton continues to accumulate bone until the third decade of life. Genetic factors exert a strong influence on peak bone mass, but lifestyle factors can also play a significant role. Strategies for reducing the risk of osteoporotic fracture include the attainment of maximal peak bone mass and the reduction of bone loss later in life. A number of lifestyle factors, including diet especially calcium and protein intake and physical activity, are amenable to interventions aimed at maximizing peak bone mass and limiting osteoporotic fracture risk Physical exercise is a lifestyle factor that has been associated with numerous health benefits and is likely to contribute to the prevention of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fracture. There is evidence to suggest that physical activity early in life contributes to the attainment of higher peak bone mass Current National Osteoporosis Foundation guidelines include recommendations of regular muscle-strengthening and weight-bearing exercise to all postmenopausal women and men ages 50 and older Although benefits in reducing bone loss might be limited, muscle-strengthening exercise, including weight training and other resistive exercises e. The progressive loss of bone mineral density BMD leading to osteopenia pre-osteoporosis and osteoporosis is usually assessed by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry DEXA at the hip and lumbar spine Several randomized , placebo -controlled clinical trials have evaluated the effect of supplemental calcium in the preservation of BMD and the prevention of fracture risk in men and women aged 50 years and older. Such modest increases may help limit the average rate of BMD loss after menopause but are unlikely to translate into meaningful fracture risk reductions. However, there was no effect when the analysis was restricted to the largest trials with the lowest risk of bias. Additionally, no reductions were found in risks of hip, vertebral and forearm fractures with calcium supplementation Because estrogen withdrawal significantly impairs intestinal absorption and renal reabsorption of calcium, the level of calcium requirement might depend on whether postmenopausal women receive hormone replacement therapy There was no significant effect of vitamin D without calcium The role and efficacy of vitamin D supplementation in strengthening bone and preventing fracture in older people remain controversial topics. The active form of vitamin D, 1,dihydroxyvitamin D, stimulates calcium absorption by promoting the synthesis of calcium-binding proteins in the intestine. This study also reported no significant difference in measures of BMD at the hip and total body between placebo- and vitamin D-treated women. Interestingly, the results of a series of trials included in three recent meta-analyses 33 , 40, 41 have suggested that supplemental vitamin D and calcium may have greater benefits in the prevention of fracture in institutionalized, older people who are also at increased risk of vitamin D deficiency and fractures compared to community dwellers 42, For more information about bone health and osteoporosis, see the article, Micronutrients and Bone Health , and visit the National Osteoporosis Foundation website. Most kidney stones are composed of calcium oxalate or calcium phosphate. Subjects with an abnormally high level of calcium in the urine hypercalciuria are at higher risk of developing kidney stones a process called nephrolithiasis High urinary oxalate level is another risk factor for calcium oxalate stone formation. Although it was initially recommended to limit dietary calcium intake in these patients, a number of prospective cohort studies have reported associations between lower total dietary calcium intake and increased risk of incident kidney stones The prospective analyses of three large cohorts, including a total of 30, men and , women followed for a combined 56 years, have indicated that the risk of kidney stones was significantly lower in individuals in the highest versus lowest quintile of dietary calcium intake from dairy or nondairy sources Mechanisms by which increased dietary calcium might reduce the risk of incident kidney stones are not fully understood. An inverse relationship was reported between total calcium intake and intestinal calcium absorption in the recent cross-sectional analysis of a cohort of 5, postmenopausal women Moreover, women with higher supplemental calcium intake and lower calcium absorption were less likely to report a history of kidney stones Adequate intake of calcium with food may reduce the absorption of dietary oxalate and lower urinary oxalate through formation of the insoluble calcium oxalate salt 51, A recent small intervention study in 10 non-stone-forming young adults observed that the ingestion of large amounts of oxalate did not increase the risk of calcium oxalate stone occurrence in the presence of recommended level of dietary calcium More controlled trials may be necessary to determine whether supplemental calcium affects kidney stone risk However, a systematic review of observational studies and randomized controlled trials that primarily reported on bone-related outcomes failed to find an effect of calcium supplementation on stone incidence A potential kidney stone risk associated with calcium supplementation may likely depend on whether supplemental calcium is co-ingested with oxalate-containing foods or consumed separately. Further research is needed to verify whether osteoporosis treatment drugs e. Current data suggest that diets providing adequate dietary calcium and low levels of animal protein, oxalate, and sodium may benefit the prevention of stone recurrence in subjects with idiopathic hypercalciuria Gestational hypertension is defined as an abnormally high blood pressure that usually develops after the 20 th week of pregnancy. Preeclampsia is characterized by poor placental perfusion and a systemic inflammation that may involve several organ systems, including the cardiovascular system, kidneys, liver, and hematological system In addition to gestational hypertension, preeclampsia is associated with the development of severe swelling edema and the presence of protein in the urine proteinuria. Eclampsia is the occurrence of seizures in association with the syndrome of preeclampsia and is a significant cause of maternal and perinatal mortality. Although cases of preeclampsia are at high risk of developing eclampsia, one-quarter of women with eclampsia do not initially exhibit preeclamptic symptoms. Risk factors for preeclampsia include genetic predisposition, advanced maternal age, first pregnancies, multiple pregnancies e. While the pathogenesis of preeclampsia is not entirely understood, nutrition and especially calcium metabolism appear to play a role. Data from epidemiological studies have suggested an inverse relationship between calcium intake during pregnancy and the incidence of preeclampsia reviewed in Secondary hyperparathyroidism high PTH level due to vitamin D deficiency in young pregnant women has been associated with high maternal blood pressure and increased risk of preeclampsia In addition, vitamin D deficiency may trigger hypertension through the inappropriate activation of the renin-angiotensin system see the article on Vitamin D. Potential beneficial effects of calcium in the prevention of preeclampsia have been investigated in several randomized , placebo -controlled studies. Greater risk reductions were reported among pregnant women at high risk of preeclampsia 5 trials; women or with low dietary calcium intake 8 trials; 10, women. Yet, based on the systematic review of high-quality randomized controlled trials, which used mostly high-dose calcium supplements, the World Health Organization WHO recently recommended that all pregnant women in areas of low-calcium intake i. Finally, the lack of effect of supplemental calcium on proteinuria reported in two trials only suggested that calcium supplementation from mid-pregnancy might be too late to oppose the genesis of preeclampsia 67, Colorectal cancer CRC is the most common gastrointestinal cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death in the US CRC is caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors, but the degree to which these two types of factors influence CRC risk in individuals varies widely. In individuals with familial adenomatous polyposis FAP or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer HNPCC , the cause of CRC is almost entirely genetic, while modifiable lifestyle factors, including dietary habits, tobacco use, and physical activities, greatly influence the risk of sporadic non-hereditary CRC. Prospective cohort studies have consistently reported an inverse association between dairy food consumption and CRC risk. Experimental studies in cell culture and animal models have suggested plausible mechanisms underlying a role for calcium, a major nutrient in dairy products, in preventing CRC In the multicenter European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition EPIC prospective study of , individuals, followed for an average of 11 years, 4, CRC cases were documented Intakes of milk, cheese, and yogurt, were inversely associated with CRC risk. Total daily intake of calcium ranged from to 2, mg in the examined studies. At present, it is not clear whether calcium supplementation is beneficial in CRC prevention. Children who are chronically exposed to lead, even in small amounts, are more likely to develop learning disabilities, behavioral problems, and to have low IQs. Deficits in growth and neurological development may occur in the infants of women exposed to lead during pregnancy and lactation. In adults, lead toxicity may result in kidney damage and high blood pressure. Although the use of lead in paint products, gasoline, and food cans has been discontinued in the US, lead toxicity continues to be a significant health problem, especially in children living in urban areas Adequate calcium intake could be protective against lead toxicity in at least two ways. Increased dietary intake of calcium is known to decrease the gastrointestinal absorption of lead. Once lead enters the body it tends to accumulate in the skeleton, where it may remain for more than 20 years. Adequate calcium intake also prevents lead mobilization from the skeleton during bone demineralization. A study of circulating concentrations of lead during pregnancy found that women with inadequate calcium intake during the second half of pregnancy were more likely to have elevated blood lead levels, probably because of increased bone demineralization, leading to the release of accumulated lead into the blood Lead in the blood of a pregnant woman is readily transported across the placenta resulting in fetal lead exposure at a time when the developing nervous system is highly vulnerable. Similar reductions in maternal lead concentrations in the blood and breast milk of lactating mothers supplemented with calcium were reported in earlier trials 84, In postmenopausal women, factors known to decrease bone demineralization, including estrogen replacement therapy and physical activity, have been inversely associated with blood lead levels High dietary calcium intake, usually associated with dairy product consumption, has been inversely related to body weight and central obesity in a number of cross-sectional studies reviewed in Cross-sectional baseline data analyses of a number of prospective cohort studies that were not designed and powered to examine the effect of calcium intake or dairy consumption on obesity or body fat have given inconsistent results Yet, a meta-analysis of 18 cross-sectional and prospective studies predicted a reduction in body mass index a relative measure of body weight; BMI of 1. Energy-restricted diets resulted in significant body weight and fat loss in all three groups. Yet, body weight and fat loss were significantly more reduced with the high-calcium diet compared to the standard diet, and further reductions were measured with the high-dairy diet compared to both high-calcium and low-calcium diets. These results suggested that while calcium intake may play a role in body weight regulation, additional benefits might be attributable to other bioactive components of dairy products, such as proteins , fatty acids , and branched chain amino acids. Yet, several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the potential impact of calcium on body weight reviewed in The most-cited mechanism is based on studies in the agouti mouse model showing that low-calcium intakes, through increasing circulating parathyroid hormone PTH and vitamin D , could stimulate the accumulation of fat lipogenesis in adipocytes fat cells Conversely, higher intakes of calcium may reduce fat storage, stimulate the breakdown of lipids lipolysis , and drive fat oxidation. Moreover, while the model suggests a role for vitamin D in lipogenesis fat storage , human studies have shown that vitamin D deficiency — rather than sufficiency — is often associated with obesity, and supplemental vitamin D might be effective in lowering body weight when caloric restriction is imposed 92, Another mechanism suggests that high-calcium diets may limit dietary fat absorption in the intestine and increase fecal fat excretion. Indeed, in the gastrointestinal tract, calcium may trap dietary fat into insoluble calcium soaps of fatty acids that are then excreted In addition, despite very limited evidence, it has also been proposed that calcium might be involved in regulating appetite and energy intake To date, there is no consensus regarding the effect of calcium on body weight changes. A meta-analysis of 29 randomized controlled trials in 2, participants median age, Yet, further subgroup analyses showed weight reductions in children and adolescents mean, At present, additional research is warranted to examine the effect of calcium intake on fat metabolism, as well as its potential benefits in the management of body weight with or without caloric restriction PMDD interferes with normal functioning, affecting daily activities and relationships Low dietary calcium intakes have been linked to PMS in early reports, and supplemental calcium has been shown to decrease symptom severity Similar positive effects were reported in earlier double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over trials that administered 1, mg of calcium daily , The relationship between calcium intake and blood pressure has been investigated extensively over the past decades. A meta-analysis of 23 large observational studies conducted in different populations worldwide found a reduction in systolic blood pressure of 0. Among participants diagnosed with hypertension , the combination diet reduced systolic blood pressure by Yet, two large systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials have examined the effect of calcium supplementation on blood pressure compared to placebo in either normotensive or hypertensive individuals , Neither of the analyses reported any significant effect of supplemental calcium on blood pressure in normotensive subjects. A small but significant reduction in systolic blood pressure, but not in diastolic blood pressure, was reported in participants with hypertension. A more recent meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled studies in individuals with elevated blood pressure found a significant reduction of 2. The modest effect of calcium on blood pressure needs to be confirmed in larger, high-quality, well-controlled trials before any recommendation is made regarding the management of hypertension. Finally, a review of the literature on the effect of high-calcium intake dietary and supplemental in postmenopausal women found either no reduction or mild and transient reductions in blood pressure More information about the DASH diet is available from the National Institutes of Health NIH. Data analysis of the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys NHANES and found inadequate calcium intakes defined as intakes below the Estimated Average Requirement [ EAR ] in However, it is typically during the most critical period for peak bone mass development that adolescents tend to replace milk with soft drinks Dairy products represent rich and absorbable sources of calcium, but certain vegetables and grains also provide calcium. However, the bioavailability of the calcium must be taken into consideration. The calcium content in calcium-rich plants in the kale family broccoli, bok choy, cabbage, mustard, and turnip greens is as bioavailable as that in milk; however, other plant-based foods contain components that inhibit the absorption of calcium. Oxalic acid, also known as oxalate, is the most potent inhibitor of calcium absorption and is found at high concentrations in spinach and rhubarb and somewhat lower concentrations in sweet potatoes and dried beans. Phytic acid phytate is a less potent inhibitor of calcium absorption than oxalate. Yeast possess an enzyme phytase that breaks down phytate in grains during fermentation , lowering the phytate content of breads and other fermented foods. Only concentrated sources of phytate, such as wheat bran or dried beans, substantially reduce calcium absorption Additional dietary constituents may affect calcium absorption see Nutrient interactions. Table 2 lists a number of calcium-rich foods, along with their calcium content. For more information on the nutrient content of foods, search USDA's FoodData Central. Most experts recommend obtaining as much calcium as possible from food because calcium in food is accompanied by other important nutrients that assist the body in utilizing calcium. However, calcium supplements may be necessary for those who have difficulty consuming enough calcium from food The "Supplement Facts" label, required on all supplements marketed in the US, lists the calcium content of the supplement as elemental calcium. Calcium preparations used as supplements include calcium carbonate, calcium citrate, calcium citrate malate, calcium lactate, and calcium gluconate. To determine which calcium preparation is in your supplement, you may have to look at the ingredient list. Calcium carbonate is generally the most economical calcium supplement. To maximize absorption, take no more than mg of elemental calcium at one time. Most calcium supplements should be taken with meals, although calcium citrate and calcium citrate malate can be taken anytime. Calcium citrate is the preferred calcium formulation for individuals who lack stomach acids achlorhydria or those treated with drugs that limit stomach acid production H 2 blockers and proton-pump inhibitors reviewed in Several decades ago, concern was raised regarding lead concentrations in calcium supplements obtained from natural sources oyster shell, bone meal, dolomite In , investigators found measurable quantities of lead in most of the 70 different preparations they tested Since then, manufacturers have reduced the amount of lead in calcium supplements to less than 0. The US Food and Drug Administration FDA has developed provisional total tolerable intake levels PTTI for lead for specific age and sex groups Because lead is so widespread and long lasting, no one can guarantee entirely lead-free food or supplements. Calcium inhibits intestinal absorption of lead, and adequate calcium intake is protective against lead toxicity, so trace amounts of lead in calcium supplementation may pose less of a risk of excessive lead exposure than inadequate calcium consumption. While most calcium sources today are relatively safe, look for supplements approved or certified by independent testing e. Malignancy and primary hyperparathyroidism are the most common causes of elevated calcium concentrations in the blood hypercalcemia Hypercalcemia has not been associated with the over consumption of calcium occurring naturally in food. Hypercalcemia has been initially reported with the consumption of large quantities of calcium supplements in combination with antacids, particularly in the days when peptic ulcers were treated with large quantities of milk, calcium carbonate antacid , and sodium bicarbonate absorbable alkali. This condition is termed calcium-alkali syndrome formerly known as milk-alkali syndrome and has been associated with calcium supplement levels from 1. Since the treatment for peptic ulcers has evolved and because of the widespread use of over-the-counter calcium supplements, the demographic of this syndrome has changed in that those at greater risk are now postmenopausal women, pregnant women, transplant recipients, patients with bulimia, and patients on dialysis , rather than men with peptic ulcers reviewed in Supplementation with calcium 0. Mild hypercalcemia may be without symptoms or may result in loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, constipation, abdominal pain, fatigue, frequent urination polyuria , and hypertension More severe hypercalcemia may result in confusion, delirium, coma, and if not treated, death 1. In , the Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine updated the tolerable upper intake level UL for calcium 9. The UL is listed in Table 3 by age group. Although the risk of forming kidney stones is increased in individuals with abnormally elevated urinary calcium hypercalciuria , this condition is not usually related to calcium intake, but rather to increased absorption of calcium in the intestine or increased excretion by the kidneys 9. Overall, increased dietary calcium intake has been associated with a decreased risk of kidney stones see Kidney stones. Concerns have also been raised regarding the risks of prostate cancer and vascular disease with high intakes of calcium. Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in men worldwide Several observational studies have raised concern that high-dairy intakes are associated with increased risk of prostate cancer The analysis of a prospective cohort study 2, men followed for nearly 25 years conducted in Iceland, a country with a high incidence of prostate cancer, found a positive association between the consumption of milk at least once daily during adolescence and developing prostate cancer later in life Another large prospective cohort study in the US followed 21, male physicians for 28 years and found that men with daily skim or low-fat milk intake of at least mL 8 oz had a higher risk of developing prostate cancer compared to occasional consumers The risk of low-grade, early-stage prostate cancer was associated with higher intake of skim milk, and the risk of developing fatal prostate cancer was linked to the regular consumption of whole milk In a cohort of 3, male health professionals diagnosed with prostate cancer, men died of prostate cancer and 69 developed metastasized prostate cancer during a median follow-up of 7. Yet, no increase in risk of prostate cancer-related mortality was associated with consumption of skim and low-fat milk, total milk, low-fat dairy products, full-fat dairy products, or total dairy products A recent meta-analysis of 32 prospective cohort studies found high versus low intakes of total dairy product 15 studies , total milk 15 studies , whole milk 6 studies , low-fat milk 5 studies , cheese 11 studies , and dairy calcium 7 studies to be associated with modest, yet significant, increases in the risk of developing prostate cancer However, there was no increase in prostate cancer risk with nondairy calcium 4 studies and calcium from supplements 8 studies. Moreover, high dairy intakes were not linked to fatal prostate cancer There is some evidence to suggest that milk consumption may result in higher circulating concentrations of insulin-like growth factor-I IGF-I , a protein known to regulate cell proliferation Circulating IGF-I concentrations have been positively correlated to the risk of developing prostate cancer in a recent meta-analysis of observational studies Milk-borne IGF-I, as well as dairy proteins and calcium, may contribute to increasing circulating IGF-I in milk consumers In the large EPIC study, which examined the consumption of dairy products in relation to cancer in , men, the risk of prostate cancer was found to be significantly higher in those in the top versusbottom quintile of both protein and calcium intakes from dairy foods Another mechanism underlying the potential relationship between calcium intake and prostate cancer proposed that high levels of dietary calcium may lower circulating concentrations of 1,dihydroxyvitamin D, the active form of vitamin D , thereby suppressing vitamin D-mediated cell differentiation However, studies to date have provided little evidence to suggest that vitamin D status can modify the association between dairy calcium and risk of prostate cancer development and progression In a multicenter, double-blind , placebo -controlled trial, healthy men mean age of While no increase in the risk for prostate cancer has been reported during a In a review of the literature published in , the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality indicated that not all epidemiological studies found an association between calcium intake and prostate cancer The review reported that 6 out of 11 observational studies failed to find statistically significant positive associations between prostate cancer and calcium intake. Inconsistencies among studies suggest complex interactions between the risk factors for prostate cancer, as well as reflect the difficulties of assessing the effect of calcium intake in free-living individuals. Several observational studies and randomized controlled trials have raised concerns regarding the potential adverse effects of calcium supplements on cardiovascular risk. The prospective study of 23, participants years old of the Heidelberg cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition cohort EPIC-Heidelberg observed that supplemental calcium intake was positively associated with the risk of myocardial infarction heart attack but not with the risk of stroke or cardiovascular disease CVD -related mortality after a mean follow-up of 11 years In addition, the secondary analyses of two randomized placebo-controlled trials initially designed to assess the effect of calcium on bone health outcomes also suggested an increased risk of CVD in participants daily supplemented with 1, mg of calcium for five to seven years , A re-analysis was performed with data from 16, women who did not take personal calcium supplements outside protocol during the five-year study However, in another randomized, double-blind , placebo-controlled trial — the Calcium Intake Fracture Outcome CAIFOS study — in elderly women median age, Also, after an additional follow-up of 4. A recent cross-sectional analysis of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey NHANES III evaluated the association between calcium intakes and cardiovascular mortality in 18, adults with no history of heart disease. No evidence of an association was observed between dietary calcium intake, supplemental calcium intake, or total calcium intake and cardiovascular mortality in either men or women A few prospective studies have reported positive correlations between high calcium concentrations in the blood and increased rates of cardiovascular events , Because supplemental calcium may have a greater effect than dietary calcium on circulating calcium concentrations see Toxicity , it has been speculated that the use of calcium supplements might promote vascular calcification — a surrogate marker of the burden of atherosclerosis and a major risk factor for cardiovascular events — by raising calcium serum concentrations. In 1, older women from the Auckland Calcium Study and healthy older men from another randomized, placebo-controlled trial of daily calcium supplementation mg or 1, mg for two years, serum calcium concentrations were found to be positively correlated with abdominal aortic calcification or coronary artery calcification However, there was no effect of calcium supplementation on measures of vascular calcification scores in men or women. Data from 1, participants of the Framingham Offspring study were also used to assess the relationship between calcium intake and vascular calcification. Again, no association was found between coronary calcium scores and total, dietary, or supplemental calcium intake in men or women Finally, an assessment of atherosclerotic lesions in the carotid artery wall of 1, participants in the CAIFOS trial was also conducted after three years of supplementation When compared with placebo, calcium supplementation showed no effect on carotid artery intimal medial thickness CIMT and carotid atherosclerosis. Because these clinical trial data are limited to analyses of secondary endpoints, meta-analyses should be interpreted with caution. There is a need for studies designed to examine the effect of calcium supplements on CVD risk as a primary outcome before definite conclusions can be drawn. Based on an updated review of the literature that included four randomized controlled trials, one nested case-control study, and 26 prospective cohort studies , the National Osteoporosis Foundation NOF and the American Society for Preventive Cardiology ASPC concluded that the use of supplemental calcium for generally healthy individuals was safe from a cardiovascular health standpoint when total calcium intakes did not exceed the UL NOF and ASPC support the use of calcium supplements to correct shortfalls in dietary calcium intake and meet current recommendations Taking calcium supplements in combination with thiazide diuretics e. High doses of supplemental calcium could increase the likelihood of abnormal heart rhythms in people taking digoxin Lanoxin for heart failure Calcium, when provided intravenously , may decrease the efficacy of calcium channel blockers However, dietary and oral supplemental calcium do not appear to affect the action of calcium channel blockers Calcium may decrease the absorption of tetracycline, quinolone class antibiotics, bisphosphonates, sotalol a β-blocker , and levothyroxine; therefore, it is advisable to separate doses of these medications and calcium-rich food or supplements by two hours before calcium or four-to-six hours after calcium Supplemental calcium can decrease the concentration of dolutegravir Tivicay , elvitegravir Vitekta , and raltegravir Isentress , three antiretroviral medications, in blood such that patients are advised to take them two hours before or after calcium supplements Intravenous calcium should not be administrated within 48 hours following intravenous ceftriaxone rocephine , a cephalosporin antibiotic, since a ceftriaxone-calcium salt precipitate can form in the lungs and kidneys and be a cause of death Use of H 2 blockers e. The topical use of calcipotriene, a vitamin D analog, in the treatment of psoriasis places patients at risk of hypercalcemia if they take calcium supplements. The presence of calcium decreases iron absorption from nonheme sources i. However, calcium supplementation up to 12 weeks has not been found to change iron nutritional status, probably due to a compensatory increase in iron absorption 1. Individuals taking iron supplements should take them two hours apart from calcium-rich food or supplements to maximize iron absorption. Although high calcium intakes have not been associated with reduced zinc absorption or zinc nutritional status, an early study in 10 men and women found that mg of calcium consumed with a meal halved the absorption of zinc from that meal see the article on Zinc Supplemental calcium mg calcium carbonate has been found to prevent the absorption of lycopene a nonprovitamin A carotenoid from tomato paste in 10 healthy adults randomized into a cross-over study The Linus Pauling Institute supports the recommended dietary allowance RDA set by the Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine. Following these recommendations should provide adequate calcium to promote skeletal health and may also decrease the risks of some chronic diseases. After adult height has been reached, the skeleton continues to accumulate bone until the third decade of life when peak bone mass is attained. Originally written in by: Jane Higdon, Ph. Linus Pauling Institute Oregon State University. Updated in April by: Jane Higdon, Ph. Updated in October by: Victoria J. Drake, Ph. Updated in August by: Barbara Delage, Ph. Updated in May by: Barbara Delage, Ph. Reviewed in September by: Connie M. Weaver, Ph. Distinguished Professor and Head of Foods and Nutrition Purdue University. The update of this article was supported by a grant from Pfizer Inc. Weaver CM. In: Erdman JJ, Macdonald I, Zeisel S, eds. Present Knowledge in Nutrition. Wesseling-Perry K, Wang H, Elashoff R, Gales B, Juppner H, Salusky IB. Lack of FGF23 response to acute changes in serum calcium and PTH in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Clapham DE. Calcium signaling. Wigertz K, Palacios C, Jackman LA, et al. Racial differences in calcium retention in response to dietary salt in adolescent girls. Am J Clin Nutr. Frassetto LA, Morris RC, Jr. Adverse effects of sodium chloride on bone in the aging human population resulting from habitual consumption of typical American diets. J Nutr. Devine A, Criddle RA, Dick IM, Kerr DA, Prince RL. A longitudinal study of the effect of sodium and calcium intakes on regional bone density in postmenopausal women. Carbone LD, Barrow KD, Bush AJ, et al. Effects of a low sodium diet on bone metabolism. J Bone Miner Metab. Sellmeyer DE, Schloetter M, Sebastian A. Potassium citrate prevents increased urine calcium excretion and bone resorption induced by a high sodium chloride diet. Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington, D. The National Academies Press. Fulgoni VL, 3 rd. Current protein intake in America: analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Ince BA, Anderson EJ, Neer RM. Lowering dietary protein to U. Recommended dietary allowance levels reduces urinary calcium excretion and bone resorption in young women. Calvez J, Poupin N, Chesneau C, Lassale C, Tome D. Protein intake, calcium balance and health consequences. Eur J Clin Nutr. Kerstetter JE, O'Brien KO, Caseria DM, Wall DE, Insogna KL. The impact of dietary protein on calcium absorption and kinetic measures of bone turnover in women. Darling AL, Millward DJ, Torgerson DJ, Hewitt CE, Lanham-New SA. Dietary protein and bone health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Grimm M, Muller A, Hein G, Funfstuck R, Jahreis G. High phosphorus intake only slightly affects serum minerals, urinary pyridinium crosslinks and renal function in young women. Kemi VE, Karkkainen MU, Rita HJ, Laaksonen MM, Outila TA, Lamberg-Allardt CJ. Low calcium:phosphorus ratio in habitual diets affects serum parathyroid hormone concentration and calcium metabolism in healthy women with adequate calcium intake. Br J Nutr. Heaney RP. Calvo MS, Moshfegh AJ, Tucker KL. Assessing the health impact of phosphorus in the food supply: issues and considerations. Adv Nutr. Heaney RP, Rafferty K. Carbonated beverages and urinary calcium excretion. Ribeiro-Alves MA, Trugo LC, Donangelo CM. Use of oral contraceptives blunts the calciuric effect of caffeine in young adult women. Barger-Lux MJ, Heaney RP, Stegman MR. Effects of moderate caffeine intake on the calcium economy of premenopausal women. Wikoff D, Welsh BT, Henderson R, et al. Systematic review of the potential adverse effects of caffeine consumption in healthy adults, pregnant women, adolescents, and children. Food Chem Toxicol. pii: S 17 doi: Haleem S, Lutchman L, Mayahi R, Grice JE, Parker MJ. Mortality following hip fracture: trends and geographical variations over the last 40 years. Kaufman JM, Reginster JY, Boonen S, et al. Treatment of osteoporosis in men. Calcium, dairy products and osteoporosis. J Am Coll Nutr. Crandall CJ, Newberry SJ, Diamant A, et al. Treatment to prevent fractures in men and women with low bone density or osteoporosis: update of a report. Rockville MD ; Rizzoli R, Bianchi ML, Garabedian M, McKay HA, Moreno LA. Maximizing bone mineral mass gain during growth for the prevention of fractures in the adolescents and the elderly. Borer KT. Physical activity in the prevention and amelioration of osteoporosis in women : interaction of mechanical, hormonal and dietary factors. Sports Med. National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician's Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Levis S, Theodore G. Summary of AHRQ's comparative effectiveness review of treatment to prevent fractures in men and women with low bone density or osteoporosis: update of the report. J Manag Care Pharm. Tai V, Leung W, Grey A, Reid IR, Bolland MJ. Calcium intake and bone mineral density: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bolland MJ, Leung W, Tai V, et al. Calcium intake and risk of fracture: systematic review. Chung M, Lee J, Terasawa T, Lau J, Trikalinos TA. Vitamin D with or without calcium supplementation for prevention of cancer and fractures: an updated meta-analysis for the U. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. Weaver CM, Alexander DD, Boushey CJ, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and risk of fractures: an updated meta-analysis from the National Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporos Int. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al. Lips P, van Schoor NM. The effect of vitamin D on bone and osteoporosis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. Gallagher JC, Yalamanchili V, Smith LM. The effect of vitamin D on calcium absorption in older women. Zhu K, Bruce D, Austin N, Devine A, Ebeling PR, Prince RL. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of calcium with or without vitamin D on bone structure and bone-related chemistry in elderly women with vitamin D insufficiency. J Bone Miner Res. Dipart Group. Patient level pooled analysis of 68 patients from seven major vitamin D fracture trials in US and Europe. Avenell A, Mak JC, O'Connell D. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures in post-menopausal women and older men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Orav EJ, et al. A pooled analysis of vitamin D dose requirements for fracture prevention. N Engl J Med. Aspray TJ, Francis RM. Fracture prevention in care home residents: is vitamin D supplementation enough? Age Ageing. Murad MH, Elamin KB, Abu Elnour NO, et al. Clinical review: The effect of vitamin D on falls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lerolle N, Lantz B, Paillard F, et al. At birth, the body contains about 26 to 30 g calcium. This amount rises quickly after birth, reaching about 1, g in women and 1, g in men by adulthood [ 1 ]. These levels remain constant in men, but they start to drop in women as a result of increases in bone remodeling due to decreased estrogen production at the start of menopause [ 1 ]. An inverse relationship exists between calcium intake and absorption. Age can also affect absorption of dietary calcium [ 1 , 4 ]. Total calcium levels can be measured in serum or plasma; serum levels are typically 8. However, serum levels do not reflect nutritional status because of their tight homeostatic control [ 4 ]. Levels of ionized or free calcium, the biologically active form, in serum are also used to measure calcium status. The normal range of ionized calcium in healthy people is 4. Dual x-ray absorptiometry testing of bone mineral density can be used to assess cumulative calcium status over the lifetime because the skeleton stores almost all calcium in the body [ 3 ]. Intake recommendations for calcium and other nutrients are provided in the Dietary Reference Intakes DRIs developed by the Food and Nutrition Board FNB at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [ 1 ]. DRI is the general term for a set of reference values used for planning and assessing nutrient intakes of healthy people. These values, which vary by age and sex, include the following:. Table 1 lists the current RDAs for calcium [ 1 ]. For adults, the main criterion that the FNB used to establish the RDAs was the amount needed to promote bone maintenance and neutral calcium balance. For infants age 0 to 12 months, the FNB established an AI that is equivalent to the mean intake of calcium in healthy, breastfed infants. For children and adolescents, the RDAs are based on intakes associated with bone accumulation and positive calcium balance. Milk, yogurt, and cheese are rich natural sources of calcium [ 1 ]. Nondairy sources include canned sardines and salmon with bones as well as certain vegetables, such as kale, broccoli, and Chinese cabbage bok choi. Most grains do not have high amounts of calcium unless they are fortified. However, they contribute to calcium intakes, even though they contain small amounts of calcium, because people consume them frequently [ 1 ]. Foods fortified with calcium in the United States include many fruit juices and drinks, tofu, and ready-to-eat cereals [ 1 , 8 ]. Calcium citrate malate is a well-absorbed form of calcium used in some fortified juices [ 3 ]. Calcium absorption varies by type of food. Certain compounds in plants e. In addition to spinach, foods with high levels of oxalic acid include collard greens, sweet potatoes, rhubarb, and beans [ 1 ]. The bioavailability of calcium from other plants that do not contain these compounds—including broccoli, kale, and cabbage—is similar to that of milk, although the amount of calcium per serving is much lower [ 3 ]. When people eat many different types of foods, these interactions with oxalic or phytic acid probably have little or no nutritional consequences. Net absorption of dietary calcium is also reduced to a small extent by intakes of caffeine and phosphorus and to a greater extent by low status of vitamin D [ ]. The U. The two most common forms of calcium in supplements are calcium carbonate and calcium citrate [ 1 ]. In people with low levels of stomach acid, the solubility rate of calcium carbonate is lower, which could reduce the absorption of calcium from calcium carbonate supplements unless they are taken with a meal [ 3 ]. Calcium citrate is less dependent on stomach acid for absorption than calcium carbonate, so it can be taken without food [ 1 ]. Other calcium forms in supplements include calcium sulfate, ascorbate, microcrystalline hydroxyapatite, gluconate, lactate, and phosphate [ 14 ]. The forms of calcium in supplements contain varying amounts of elemental calcium. Elemental calcium is listed in the Supplement Facts panel, so consumers do not need to calculate the amount of calcium supplied by various forms of calcium in supplements. The percentage of calcium absorbed from supplements, as with that from foods, depends not only on the source of calcium but also on the total amount of elemental calcium consumed at one time; as the amount increases, the percentage absorbed decreases. Absorption from supplements is highest with doses of mg or less [ 15 ]. Some individuals who take calcium supplements might experience gastrointestinal side effects, including gas, bloating, constipation, or a combination of these symptoms. Calcium carbonate appears to cause more of these side effects than calcium citrate, especially in older adults who have lower levels of stomach acid [ 1 ]. Symptoms can be alleviated by switching to a supplement containing a different form of calcium, taking smaller calcium doses more often during the day, or taking the supplement with meals. Because of its ability to neutralize stomach acid, calcium carbonate is contained in some over-the-counter antacid products, such as Tums and Rolaids. Depending on its strength, each chewable pill or soft chew provides about to mg of calcium [ 14 ]. A substantial proportion of people in the United States consume less than recommended amounts of calcium. Average daily intakes of calcium from foods and beverages are 1, mg for men age 20 and older and mg for women [ 18 ]. For children age 2—19, mean daily intakes of calcium from foods and beverages range from to 1, mg [ 18 ]. Average daily calcium intakes from both foods and supplements are 1, mg for men, 1, mg for women, and to 1, mg for children [ 18 ]. Poverty is also associated with a higher risk of inadequacy. NHANES data from to show that the risk of inadequate calcium intakes less than to 1, mg is Calcium deficiency can reduce bone strength and lead to osteoporosis, which is characterized by fragile bones and an increased risk of falling [ 1 ]. Calcium deficiency can also cause rickets in children and other bone disorders in adults, although these disorders are more commonly caused by vitamin D deficiency. In children with rickets, the growth cartilage does not mineralize normally, which can lead to irreversible changes in the skeletal structure [ 1 ]. Another effect of chronic calcium deficiency is osteomalacia, or defective bone mineralization and bone softening, which can occur in adults and children [ 1 ]. For rickets and osteomalacia, the requirements for calcium and vitamin D appear to be interrelated in that the lower the serum vitamin D level measured as hydroxyvitamin D [25 OH D] , the more calcium is needed to prevent these diseases [ 21 ]. Hypocalcemia serum calcium level less than 8. Hypocalcemia can be asymptomatic, especially when it is mild or chronic [ 23 ]. When signs and symptoms do occur, they can range widely because low serum calcium levels can affect most organs and symptoms [ 24 ]. The most common symptom is increased neuromuscular irritability, including perioral numbness, tingling in the hands and feet, and muscle spasms [ 23 ]. More severe signs and symptoms can include renal calcification or injury; brain calcification; neurologic symptoms e. Menopause leads to bone loss because decreases in estrogen production reduce calcium absorption and increase urinary calcium loss and calcium resorption from bone [ 1 ]. Over time, these changes lead to decreased bone mass and fragile bones [ 1 ]. The calcium RDA is 1, mg for women older than 50 years vs. People with lactose intolerance, those with an allergy to milk, and those who avoid eating dairy products including vegans have a higher risk of inadequate calcium intakes because dairy products are rich sources of calcium [ 1 , 27 ]. Options for increasing calcium intakes in individuals with lactose intolerance include consuming lactose-free or reduced-lactose dairy products, which contain the same amounts of calcium as regular dairy products [ 1 , 3 ]. Those who avoid dairy products because of allergies or for other reasons can obtain calcium from nondairy sources, such as some vegetables e. However, these individuals typically need to eat foods fortified with calcium or take supplements to obtain recommended amounts [ 28 ]. This section focuses on six health conditions and diseases in which calcium might play a role: bone health in older adults, cancer, cardiovascular disease CVD , preeclampsia, weight management, and metabolic syndrome. Bone is constantly being remodeled. Declining levels of estrogen in women during menopause and for approximately 5 years afterward lead to rates of bone resorption that are higher than rates of bone formation, resulting in a rapid decrease in bone mass [ 7 ]. Over time, postmenopausal women can develop osteoporosis, in which bone strength is compromised because of lower BMD and bone quality [ 1 ]. Age-related bone loss can also occur in men and lead to osteoporosis, but fracture risk tends to increase in older men about 5 to 10 years later than in older women [ 1 ]. Osteoporosis increases the risk of fractures, especially of the hip, vertebrae, and forearms [ 1 , 7 ]. FDA has approved a health claim for the use of supplements containing calcium and vitamin D to reduce the risk of osteoporosis [ 29 ]. However, not all research supports this claim. In spite of the importance of calcium in bone health, observational evidence is mixed on the link between calcium intakes and measures of bone strength in older adults. Support for such a link comes from an analysis of — NHANES cross-sectional data on 2, adults age 60 and older Results were similar in of the women who were followed for 6 years, even though mean daily intakes of calcium dropped by an average of 40 mg during this period. Some but not all clinical trials have found that calcium supplementation can improve bone health in older adults. On average, women lost 1. Several recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have found that supplementation with calcium alone or a combination of calcium and vitamin D increases BMD in older adults. For example, a systematic review and meta-analysis included 15 RCTs in postmenopausal women but did not include the two studies described in the previous paragraph in 78, women, of which 37, were in the intervention group and 40, were in the control group [ 34 ]. Supplementation with both calcium and vitamin D or consumption of dairy products fortified with both nutrients increased total BMD as well as BMD at the lumbar spine, arms, and femoral neck. However, in subgroup analyses, calcium had no effect on femoral neck BMD. Earlier systematic reviews and meta-analyses found a positive relationship between calcium and vitamin D supplementation and increased BMD in older males [ 35 ] and between higher calcium intakes from dietary sources or supplements and higher BMD in adults older than 50 [ 25 ]. However, whether these BMD increases were clinically significant is not clear. As with the evidence on the link between increased calcium intakes and reductions in BMD loss, the findings of research on the use of calcium supplementation to prevent fractures in older adults are mixed. For the most part, the observational evidence does not show that increasing calcium intakes reduces the risk of fractures and falls in older adults. For example, a longitudinal cohort study of 1, women age 42 to 52 years at baseline who were followed for 10—12 years found that fracture risk was not significantly different in calcium supplement users some of whom also took vitamin D supplements and nonusers, even though supplement use was associated with less BMD loss throughout the study period [ 36 ]. Some clinical trial evidence shows that supplements containing a combination of calcium and vitamin D can reduce the risk of fractures in older adults. However, findings were negative in another systematic review and meta-analysis that included 14 RCTs of calcium supplementation and 13 trials comparing calcium and vitamin D supplements with hormone therapy, placebo, or no treatment in participants older than 50 years [ 38 ]. The results showed that calcium supplementation alone had no effect on risk of hip fracture, and supplementation with both calcium and vitamin D had no effect on risk of hip fracture, nonvertebral fracture, vertebral fracture, or total fracture. Similarly, a systematic review of 11 RCTs in 51, adults age 50 and older found that supplementation with vitamin D and calcium for 2 to 7 years had no impact on risk of total fractures or of hip fractures [ 39 ]. Preventive Services Task Force USPSTF concluded with moderate certainty that daily doses of less than 1, mg calcium and less than IU 10 mcg vitamin D do not prevent fractures in postmenopausal women and that the evidence on larger doses of this combination is inadequate to assess the benefits in this population [ 40 ]. The USPSTF also determined the evidence on the benefits of calcium supplementation alone or with vitamin D to be inadequate to assess its effect on preventing fractures in men and premenopausal women. Additional research is needed before conclusions can be drawn about the use of calcium supplements to improve bone health and prevent fractures in older adults. Calcium might help reduce the risk of cancer, especially in the colon and rectum [ 1 ]. However, evidence on the relationship between calcium intakes from foods or supplements and different forms of cancer is inconsistent [ 4 ]. Most clinical trial evidence does not support a beneficial effect of calcium supplements on cancer incidence. A 4-year study of 1, mg calcium and 2, IU 50 mcg vitamin D or placebo daily for 4 years in 2, healthy women age 55 years and older showed that supplementation did not reduce the risk of all types of cancer [ 41 ]. The large WHI study described above also found no benefit of supplemental calcium and vitamin D on cancer incidence [ 42 ]. In addition, a meta-analysis of 10 RCTs that included 10, individuals who took supplements containing mg calcium or more without vitamin D for a mean of 3. However, one large clinical trial did find that calcium supplements reduce cancer risk. |

| What is Calcium and What Does it Do? | Article CAS Google Scholar Pattanaungkul S, Riggs BL, Yergey AL et al. About Mayo Clinic. Comparison of dietary calcium with supplemental calcium and other nutrients as factors affecting the risk for kidney stones in women. Your body doesn't produce calcium, so you must get it through other sources. Financial Services. |

| Calcium/Vitamin D Requirements, Recommended Foods & Supplements | Am J Hypertens. In contrast, a longitudinal study in 2, participants in Portugal evaluated at ages 13 and 21 years found no association between total dietary and supplemental calcium intake at age 13 and body mass index BMI at age 21 after the analysis was adjusted for energy intake [ 87 ]. Mechanisms by which increased dietary calcium might reduce the risk of incident kidney stones are not fully understood. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: burden of illness and treatment update. Individuals taking iron supplements should take them two hours apart from calcium-rich food or supplements to maximize iron absorption. |

Calcium absorption -

Plant-based milks oat, almond, rice, etc. may or may not be calcium-fortified, so it is important to check the label of these products if you intend to use these in place of regular dairy milk to boost your calcium intake.

It is much better to get calcium from foods which also provide other nutrients than from calcium supplements.

But if you have difficulty eating enough foods rich in calcium, you might need to consider a calcium supplement, especially if you are at risk of developing osteoporosis.

Too much calcium may cause gastrointestinal upsets such as bloating and constipation and, rarely, other complications such as kidney stones. A report published in , and widely reported in the media, found a possible link between calcium supplements and an increased risk of heart disease , particularly in older women.

If you have any concerns about calcium supplements, talk to your doctor or other registered healthcare professional. Some of the factors that can reduce calcium in your bones and lower your bone density weaken your bones include:.

This page has been produced in consultation with and approved by:. Content on this website is provided for information purposes only. Information about a therapy, service, product or treatment does not in any way endorse or support such therapy, service, product or treatment and is not intended to replace advice from your doctor or other registered health professional.

The information and materials contained on this website are not intended to constitute a comprehensive guide concerning all aspects of the therapy, product or treatment described on the website.

All users are urged to always seek advice from a registered health care professional for diagnosis and answers to their medical questions and to ascertain whether the particular therapy, service, product or treatment described on the website is suitable in their circumstances.

The State of Victoria and the Department of Health shall not bear any liability for reliance by any user on the materials contained on this website. Skip to main content.

Healthy eating. Home Healthy eating. Actions for this page Listen Print. Summary Read the full fact sheet.

On this page. What is calcium? Role of calcium in the body Calcium and dairy food Too little calcium can weaken bones Calcium needs vary throughout life People with special calcium needs Good sources of calcium Calcium supplements Calcium supplements — complications Lifestyle can affect bone strength Where to get help.

Food type Examples Calcium per serve mg Milk and milk products Milk, yoghurt, cheese and buttermilk One cup of milk, a g tub of yoghurt or ml of calcium-fortified soymilk provides around mg calcium.

Soy and tofu Tofu depending on type or tempeh and calcium fortified soy drinks One cup, or g of tofu contains around mg of calcium. Fish Sardines and canned salmon bones included Half a cup of canned salmon contains mg of calcium. Nuts and seeds Brazil nuts, almonds and sesame seed paste tahini Fifteen almonds contain about 40 mg of calcium.

Calcium-fortified foods Breakfast cereals, fruit juices, bread, some plant-based milks One cup of calcium-fortified breakfast cereal 40 g contains up to mg of calcium.

Calcium and bone health External Link , Healthy Bones Australia. Calcium External Link , Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand, National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Government.

Are calcium supplements dangerous? External Link , healthdirect. Australian health survey: Usual nutrient intakes, External Link , , Australian Bureau of Statistics. Serve sizes External Link , Eat for Health, National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Government.

Poole R, Kennedy O, Roderick P, et al. Give feedback about this page. Was this page helpful? Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disease characterized by decreased bone strength and increased risk of fractures.

Although osteoporosis affects both aging men and women, it is more frequently observed in postmenopausal women.

In addition to low estradiol, low serum 25 OH D 3 is also associated with adverse skeletal outcomes. This level, as indicated by the Institute of Medicine, is associated with reduced fracture risk.