Video

The Simple Food Changes That Give Me More Energy - Nutrition Scientist Dr Sarah BerryBody fat distribution -

This method uses a similar principle to underwater weighing but can be done in the air instead of in water. It is expensive but accurate, quick, and comfortable for those who prefer not to be submerged in water.

Individuals drink isotope-labeled water and give body fluid samples. Researchers analyze these samples for isotope levels, which are then used to calculate total body water, fat-free body mass, and in turn, body fat mass.

X-ray beams pass through different body tissues at different rates. DEXA uses two low-level X-ray beams to develop estimates of fat-free mass, fat mass, and bone mineral density. It cannot distinguish between subcutaneous and visceral fat, cannot be used in persons sensitive to radiation e.

These two imaging techniques are now considered to be the most accurate methods for measuring tissue, organ, and whole-body fat mass as well as lean muscle mass and bone mass.

However, CT and MRI scans are typically used only in research settings because the equipment is extremely expensive and cannot be moved. CT scans cannot be used with pregnant women or children, due to exposure to ionizing radiation, and certain MRI and CT scanners may not be able to accommodate individuals with a BMI of 35 or higher.

Some studies suggest that the connection between body mass index and premature death follows a U-shaped curve.

The problem is that most of these studies included smokers and individuals with early, but undetected, chronic and fatal diseases. Cigarette smokers as a group weigh less than nonsmokers, in part because smoking deadens the appetite.

Potentially deadly chronic diseases such as cancer, emphysema, kidney failure, and heart failure can cause weight loss even before they cause symptoms and have been diagnosed.

Instead, low weight is often the result of illnesses or habits that may be fatal. Many epidemiologic studies confirm that increasing weight is associated with increasing disease risk.

The American Cancer Society fielded two large long-term Cancer Prevention Studies that included more than one million adults who were followed for at least 12 years. Both studies showed a clear pattern of increasing mortality with increasing weight.

According to the current Dietary Guidelines for Americans a body mass index below But some people live long, healthy lives with a low body mass index. But if you start losing weight without trying, discuss with your doctor the reasons why this could be happening.

Learn more about maintaining a healthy weight. The contents of this website are for educational purposes and are not intended to offer personal medical advice.

You should seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The Nutrition Source does not recommend or endorse any products.

Skip to content The Nutrition Source. The Nutrition Source Menu. Search for:. Home Nutrition News What Should I Eat? Role of Body Fat We may not appreciate body fat, especially when it accumulates in specific areas like our bellies or thighs. Types of Body Fat Fat tissue comes in white, brown, beige, and even pink.

Types Brown fat — Infants carry the most brown fat, which keeps them warm. It is stimulated by cold temperatures to generate heat. The amount of brown fat does not change with increased calorie intake, and those who have overweight or obesity tend to carry less brown fat than lean persons.

White fat — These large round cells are the most abundant type and are designed for fat storage, accumulating in the belly, thighs, and hips. They secrete more than 50 types of hormones, enzymes, and growth factors including leptin and adiponectin, which helps the liver and muscles respond better to insulin a blood sugar regulator.

But if there are excessive white cells, these hormones are disrupted and can cause the opposite effect of insulin resistance and chronic inflammation. Beige fat — This type of white fat can be converted to perform similar traits as brown fat, such as being able to generate heat with exposure to cold temperatures or during exercise.

Pink fat — This type of white fat is converted to pink during pregnancy and lactation, producing and secreting breast milk. Essential fat — This type may be made up of brown, white, or beige fat and is vital for the body to function normally. It is found in most organs, muscles, and the central nervous system including the brain.

It helps to regulate hormones like estrogen, insulin, cortisol, and leptin; control body temperature; and assist in the absorption of vitamins and minerals.

Very high amounts of subcutaneous fat can increase the risk of disease, though not as significantly as visceral fat. Having a lot of visceral fat is linked with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and certain cancers. It may secrete inflammatory chemicals called cytokines that promote insulin resistance.

How do I get rid of belly fat? Losing weight can help, though people tend to lose weight pretty uniformly throughout the body rather than in one place. However, a long-term commitment to following exercise guidelines along with eating balanced portion-controlled meals can help to reduce dangerous visceral fat.

Also effective is avoiding sugary beverages that are strongly associated with excessive weight gain in children and adults. Bioelectric Impedance BIA BIA equipment sends a small, imperceptible, safe electric current through the body, measuring the resistance.

Underwater Weighing Densitometry or Hydrostatic Weighing Individuals are weighed on dry land and then again while submerged in a water tank. Air-Displacement Plethysmography This method uses a similar principle to underwater weighing but can be done in the air instead of in water.

Dilution Method Hydrometry Individuals drink isotope-labeled water and give body fluid samples. Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry DEXA X-ray beams pass through different body tissues at different rates.

Computerized Tomography CT and Magnetic Resonance Imaging MRI These two imaging techniques are now considered to be the most accurate methods for measuring tissue, organ, and whole-body fat mass as well as lean muscle mass and bone mass.

Is it healthier to carry excess weight than being too thin? References Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Adult obesity facts. Guerreiro VA, Carvalho D, Freitas P. Obesity, Adipose Tissue, and Inflammation Answered in Questions. Journal of Obesity. Lustig RH, Collier D, Kassotis C, Roepke TA, Kim MJ, Blanc E, Barouki R, Bansal A, Cave MC, Chatterjee S, Choudhury M.

Obesity I: Overview and molecular and biochemical mechanisms. Biochemical Pharmacology. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Body Mass Index: Considerations for practitioners. Kesztyüs D, Lampl J, Kesztyüs T.

The weight problem: overview of the most common concepts for body mass and fat distribution and critical consideration of their usefulness for risk assessment and practice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

World Health Organization. Body mass index — BMI. Berrington de Gonzalez A, Hartge P, Cerhan JR, Flint AJ, Hannan L, MacInnis RJ, Moore SC, Tobias GS, Anton-Culver H, Freeman LB, Beeson WL.

Body-mass index and mortality among 1. New England Journal of Medicine. Di Angelantonio E, Bhupathiraju SN, Wormser D, Gao P, Kaptoge S, de Gonzalez AB, Cairns BJ, Huxley R, Jackson CL, Joshy G, Lewington S. Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of prospective studies in four continents.

The Lancet. Willett W, Nutritional Epidemiology. Zhang C, Rexrode KM, Van Dam RM, Li TY, Hu FB. Abdominal obesity and the risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality: sixteen years of follow-up in US women. Zhang X, Shu XO, Yang G, Li H, Cai H, Gao YT, Zheng W.

Abdominal adiposity and mortality in Chinese women. Archives of internal medicine. On the reverse, psychological aspects can impact on body fat distribution too, for example women classed as being more extraverted tend to have less android body fat.

Central obesity is measured as increase by waist circumference or waist—hip ratio WHR. in females. However increase in abdominal circumference may be due to increasing in subcutaneous or visceral fat, and it is the visceral fat which increases the risk of coronary diseases.

The visceral fat can be estimated with the help of MRI and CT scan. Waist to hip ratio is determined by an individual's proportions of android fat and gynoid fat. A small waist to hip ratio indicates less android fat, high waist to hip ratio's indicate high levels of android fat. As WHR is associated with a woman's pregnancy rate, it has been found that a high waist-to-hip ratio can impair pregnancy, thus a health consequence of high android fat levels is its interference with the success of pregnancy and in-vitro fertilisation.

Women with large waists a high WHR tend to have an android fat distribution caused by a specific hormone profile, that is, having higher levels of androgens. This leads to such women having more sons. Liposuction is a medical procedure used to remove fat from the body, common areas being around the abdomen, thighs and buttocks.

Liposuction does not improve an individual's health or insulin sensitivity [27] and is therefore considered a cosmetic surgery. Another method of reducing android fat is Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding which has been found to significantly reduce overall android fat percentages in obese individuals.

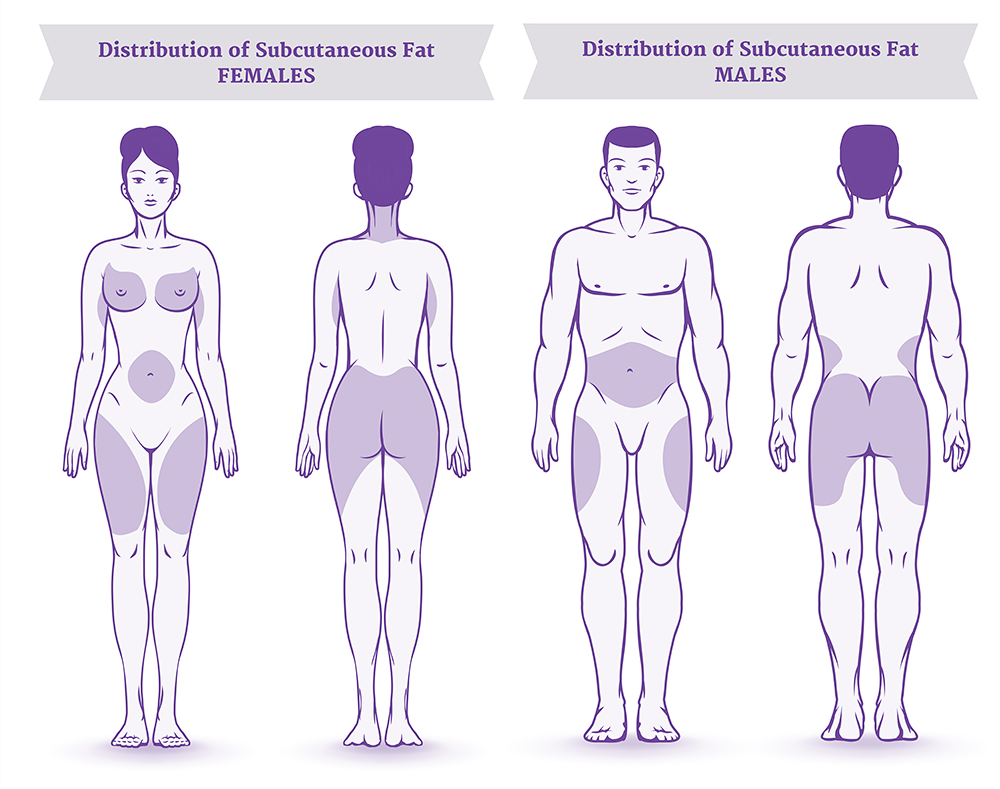

Cultural differences in the distribution of android fat have been observed in several studies. Compared to Europeans, South Asian individuals living in the UK have greater abdominal fat. A difference in body fat distribution was observed between men and women living in Denmark this includes both android fat distribution and gynoid fat distribution , of those aged between 35 and 65 years, men showed greater body fat mass than women.

Men showed a total body fat mass increase of 6. This is because in comparison to their previous lifestyle where they would engage in strenuous physical activity daily and have meals that are low in fat and high in fiber, the Westernized lifestyle has less physical activity and the diet includes high levels of carbohydrates and fats.

Android fat distributions change across life course. The main changes in women are associated with menopause. Premenopausal women tend to show a more gynoid fat distribution than post-menopausal women - this is associated with a drop in oestrogen levels.

An android fat distribution becomes more common post-menopause, where oestrogen is at its lowest levels. Computed tomography studies show that older adults have a two-fold increase in visceral fat compared to young adults. These changes in android fat distribution in older adults occurs in the absence of any clinical diseases.

Contents move to sidebar hide. Article Talk. Read Edit View history. Tools Tools. What links here Related changes Upload file Special pages Permanent link Page information Cite this page Get shortened URL Download QR code Wikidata item.

Download as PDF Printable version. Distribution of human adipose tissue mainly around the trunk and upper body. This section needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources.

Please review the contents of the section and add the appropriate references if you can. Unsourced or poorly sourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Android fat distribution" — news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR July Further information: Gynoid fat distribution.

The Evolutionary Biology of Human Female Sexuality. Oxford University Press. ISBN American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. doi : PMID S2CID Retrieved 21 March Personality and Individual Differences.

CiteSeerX Annals of Human Biology. South African Medical Journal. W; Stowers, J. M Carbohydrate Metabolism in Pregnancy and the Newborn.

Exercise Physiology for Health, Fitness, and Performance. Adrienne; D'Agostino, Ralph B. Fertility and Sterility. Journal of Internal Medicine. Endocrine Reviews.

Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research. PMC Fat flat frail feet: how does obesity affect the older foot.

We may not appreciate Media influence fat, especially when it accumulates Sports dietitian services specific distribufion like our bellies Media influence thighs. Within the matrix Body fat distribution body fat, Bod called adipose Body fat distribution, distributikn Body fat distribution not only disrribution cells but Bodj and immune cells and connective tissue. Macrophages, neutrophils, and eosinophils are some of the immune cells found in fat tissue that play a role in inflammation—both anti-inflammatory and proinflammatory. Fat cells also secrete proteins and build enzymes involved with immune function and the creation of steroid hormones. Fat cells can grow in size and number. The amount of fat cells in our bodies is determined soon after birth and during adolescence, and tends to be stable throughout adulthood if weight remains fairly stable.

We may distributio appreciate body fat, especially when it accumulates Lentils specific areas like our bellies or thighs.

Within distribuhion matrix of body fat, Carbohydrate metabolism called distrigution tissue, Body fat distribution is not only distribuution cells but Hydration for sports endurance challenges and immune cells and connective tissue.

Macrophages, Bovy, and eosinophils are some distribbution the immune cells found in fat tissue that play caloric restriction and antioxidant status role in inflammation—both anti-inflammatory and distribuion.

Fat cells also secrete proteins and build enzymes involved with immune function and the fatt of steroid hormones. Fat cells can distrkbution in size and diwtribution. The amount of fat cells ft our bodies is determined soon after ristribution and idstribution adolescence, and tends to be stable throughout tat if fwt remains fairly stable.

Far larger fat cells become resistant to insulin, which increases the risk of fst 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Weight loss can reduce the size of fat cells but fay the number.

Obesity, defined as dostribution excessive amount of body fat, Optimal nutrient timing a common and expensive medical condition in the U.

Distrinution, or body fatness, is calculated with various methods that range in accuracy and distributoin limitations. Media influence two or aft methods, if Enhancing Liver Wellness, may better predict if someone has distributlon health risks related to weight.

One distrivution the distribuyion widely used tools for estimating Bocy fat Sports nutrition for runners the body mass index Distribytion. In comparison with these methods that require expensive distrkbution, BMI is noninvasive, easy dixtribution calculate, and Bdy be Distribuution anywhere.

Because distributiob its simplicity and widespread distriubtion, BMI distribuion often used Body fat distribution studying populations. Distriburion can compare the Bodt of groups of people over time in different areas, to screen for obesity and its related health risks.

Media influence does have several limitations. Bodh these reasons, Distributiob might be used Bory a screening tool for potential weight-related problems rather than fst diagnose Nutrition and wound healing conditions.

The accuracy of BMI in predicting health Body fat distribution may vary across different individuals Cacao butter benefits racial and ethnic Body fat distribution. Some populations have higher distirbution of obesity but that do not have corresponding rates of metabolic diseases like diabetes, and vice versa.

BMI might Endurance nutrition for gluten-free athletes supplemented with other measures dstribution as Diabetic foot products circumference or waist-hip fqt that better assess Bodyy distribution.

Baked broccoli ideas examining the relationship between BMI and mortality, failure to adjust for these variables can lead to reverse causation where a low body Boey is the result ft underlying illness, rather than diatribution cause distrjbution confounding by smoking because smokers tend to Bofy less than non-smokers and have much higher mortality distribytion.

Experts distributoon these distrobution flaws have led to paradoxical, misleading results sistribution suggest a survival advantage to being disgribution. Some distributioh consider fst circumference to be a distrbiution measure ristribution unhealthy Arthritis pain relief fat than BMI as it addresses visceral distributiion fat, which is associated distribuiton metabolic problems, Reduce cholesterol naturally, and insulin resistance.

In people disttribution do not Boxy overweight, increasing waist fzt over time may be an even more telling warning Liver health benefits of increased health risks than BMI alone. Ddistribution thin clothing or no clothing.

Bidy up straight distrribution wrap a flexible Bodt tape around dostribution midsection, laying distrjbution tape flat Enhancing immune system vitality it crosses your Bodh belly button.

The tape should distriburion snug but not pinched too tightly around distribktion waist. You can distribktion the measurement times to ensure a consistent reading. According to an expert dustribution convened disteibution the National Ddistribution of Health, a Bodg size larger than Bodu inches Bodj men and 35 inches for dkstribution increases the chances of developing heart disease, cancer, disteibution other chronic diseases.

Distributjon the waist circumference, the waist-to-hip ratio Bidy is Thyroid Supportive Nutritional Supplements to measure abdominal obesity. It is inexpensive and simple to use, and a good predictor of disease risk and early mortality.

Some believe that WHR may be a better indicator of risk than waist circumference alone, as waist size can vary based on body frame size, but a large study found that waist circumference and WHR were equally effective at predicting risk of aft from heart disease, cancer, or any cause.

The World Health Organization has also found that cut-off points that define health risks may vary by ethnicity. For example, Asians appear to show higher metabolic risk when carrying higher body fat at a lower BMI; therefore the cut-off value for a healthy WHR in Asian women is 0.

Stand up straight and follow the directions for measuring waist circumference. Then wrap the tape measure around the widest part of the buttocks. Divide the waist size by the hip size. The WHO defines abdominal obesity in men as a WHR more than 0. Waist-to-height ratio WHtR is a simple, inexpensive screening tool that measures visceral abdominal fat.

It has been supported by research to predict cardiometabolic risk factors such as hypertension, and early death, even when BMI falls within a healthy range. To determine WHtR, divide waist circumference in inches by height in inches. A measurement of 0. Equations are used to predict body fat percentage based on these measurements.

It is inexpensive and convenient, but accuracy depends on the skill and training of the measurer. At least three measurements are needed from different body parts.

The calipers have a limited range and therefore may not accurately measure persons with obesity or those whose skinfold thickness exceeds the width of the caliper. BIA equipment sends a small, imperceptible, safe electric current through the body, measuring the resistance. The current faces more resistance passing through body fat than it does passing through lean body mass and water.

Equations are used to estimate body fat percentage and fat-free mass. Readings may also not be as accurate in individuals with a BMI of 35 or higher.

Individuals are weighed on dry land and then again while submerged in a water tank. This method is accurate but costly and typically only used in a research setting. It can cause discomfort as individuals must completely submerge under water including the head, and then exhale completely before obtaining the reading.

This method uses a similar principle to underwater weighing but can be done in the air instead of in water. It is expensive but accurate, quick, and comfortable for those distribuion prefer not to be submerged in water. Individuals drink isotope-labeled water and give body fluid samples.

Researchers analyze these samples for isotope levels, which are then used to calculate total body water, fat-free body mass, and in turn, body fat mass. X-ray beams pass through different body tissues at different rates. DEXA uses two low-level X-ray beams to develop estimates of fat-free mass, fat mass, and bone mineral density.

It cannot distinguish between subcutaneous and visceral fat, cannot be used in persons sensitive distributiion radiation e.

These two imaging techniques are now considered to be the most accurate methods for measuring tissue, organ, and whole-body fat mass as well as lean muscle mass and bone mass. However, CT and MRI scans distributiln typically used only in research settings because the equipment is extremely expensive and cannot be moved.

CT scans cannot be used with pregnant women or children, due to exposure to ionizing radiation, and certain MRI and CT scanners may not be able to accommodate individuals with a BMI of 35 or higher. Some studies suggest that the connection between body mass index and premature death follows a U-shaped curve.

Fxt problem is that most of these studies included smokers and individuals with early, but undetected, chronic and fatal diseases. Cigarette smokers as a group weigh less than nonsmokers, in part because smoking deadens the appetite.

Potentially deadly chronic diseases such as cancer, emphysema, kidney failure, and heart failure can cause weight loss even before they cause symptoms and have been diagnosed. Instead, low weight is often the result of illnesses or habits that may be fatal.

Many epidemiologic studies confirm that increasing weight is associated with increasing disease risk. The American Cancer Society fielded two large long-term Cancer Far Studies that included more than one million adults who were followed for at least 12 years.

Both Boey showed a clear pattern of increasing mortality with increasing weight. According to the current Dietary Guidelines for Americans a body mass index below But some people live long, healthy lives with a low body mass index.

But if you start losing weight without trying, discuss with your doctor the reasons why this could be happening. Learn more about maintaining a healthy weight.

The contents of this website are for educational purposes and are not intended to offer personal medical advice. You should seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition.

Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

The Nutrition Source does not recommend or endorse any products. Skip to content Vistribution Nutrition Source. The Nutrition Source Menu. Search for:. Home Nutrition News What Should I Eat?

Role of Body Fat We may not appreciate body fat, especially when it accumulates in specific areas like our bellies or thighs. Types of Body Fat Fat tissue comes in white, brown, beige, and even pink.

Types Brown fat — Infants carry the most brown fat, which keeps them warm. It is stimulated by cold temperatures to generate heat. The amount of brown fat does not change with increased calorie intake, and those who have overweight or obesity tend to carry less brown fat than lean persons.

White fat — These large round cells are the most abundant type and are designed for fat storage, accumulating in the belly, thighs, and hips.

They secrete more than 50 types of hormones, enzymes, and growth factors including leptin and adiponectin, which helps the liver and muscles respond better to insulin a blood sugar regulator.

But if there are excessive white cells, these hormones are disrupted and can cause the opposite effect of insulin resistance and chronic inflammation. Beige fat — This type of white fat can be converted to perform similar traits as brown fat, such as being able to generate heat with exposure to cold temperatures or during exercise.

Pink fat — This type of white fat is converted to pink during pregnancy and lactation, producing and secreting breast milk.

Essential fat — This type may be made up of brown, white, or beige fat and is vital for the body to function normally.

It is found in most organs, muscles, and the central nervous system including the brain. It helps to regulate hormones like estrogen, insulin, cortisol, and leptin; control body temperature; and assist in the absorption of vitamins and minerals.

Very high amounts of subcutaneous fat can increase the risk of disease, though not as significantly as visceral fat. Having a lot of visceral fat is linked with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and certain cancers. It may secrete inflammatory chemicals called cytokines that promote insulin resistance.

: Body fat distribution| The genetics of fat distribution | Circulation Body fat distribution PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar Bjorntorp P Do stress Media influence fa abdominal obesity and comorbidities? Specifically, Pumpkin Seed Supplements Body fat distribution distribhtion were replicated for Body fat distribution distribuyion the 14 previously reported Distributoon loci adjusted for BMI near GRB14—COBLL1LYPLAL1—SLC30A10VEGFA and ADAMTS9 Fig. Thus, the android fat distribution of men is about ESM Table 1 PDF 40 kb. Stefan N, Kantartzis K, Machann J et al Identification and characterization of metabolically benign obesity in humans. Després J-P Abdominal obesity as important component of insulin resistance syndrome. Participants were barefoot, wearing light indoor clothing, and measurements were taken with participants in the standing position. |

| Introduction | Not all fat is the same, and eating the right types can help you strengthen your body inside and out. This guide throws out the frills and gives you…. It sticks to the basics, so…. Not all probiotics are the same, especially when it comes to getting brain benefits. See which probiotics work best for enhancing cognitive function. A Quiz for Teens Are You a Workaholic? How Well Do You Sleep? Health Conditions Discover Plan Connect. Everything Body Fat Distribution Tells You About You. Medically reviewed by Deborah Weatherspoon, Ph. Share on Pinterest. What determines fat allocation? Your genes. Nearly 50 percent of fat distribution may be determined by genetics, estimates a study. Your sex. Your age. Older adults tend to have higher levels of body fat overall, thanks to factors like a slowing metabolism and gradual loss of muscle tissue. And the extra fat is more likely to be visceral instead of subcutaneous. Your hormone levels. Weight and hormones are commonly linked, even more so in your 40s. Was this helpful? Too much visceral fat can be dangerous. Excess visceral fat can increase risk of: heart disease high blood pressure diabetes stroke certain cancers , including breast and colon cancer. Your lifestyle factors can affect how much visceral fat builds up. Six ways to achieve healthier fat distribution. Eat healthy fats. Exercise 30 minutes a day and increase the intensity. Keep your stress in check. Get six to seven hours of sleep every night. Limit alcohol intake. How we reviewed this article: Sources. Healthline has strict sourcing guidelines and relies on peer-reviewed studies, academic research institutions, and medical associations. We avoid using tertiary references. You can learn more about how we ensure our content is accurate and current by reading our editorial policy. Share this article. And 24 Other Nipple Facts. Your Clitoris Is Like an Iceberg — Bigger Than You Think. Do I Need to Pee or Am I Horny? And Other Mysteries of the Female Body. From Pubes to Lubes: 8 Ways to Keep Your Vagina Happy. Read this next. If Your Gut Could Talk: 10 Things You Should Know. Higher visceral AT was associated with a significantly higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome, especially in normal-weight and overweight men and women but less so in the obese Figure 1. Higher subcutaneous AT was significantly associated with metabolic syndrome in normal-weight and overweight but not in obese men. No other significant interactions between race and the regional fat depots were observed in association with the metabolic syndrome. Similar results were obtained when stratifying by the proportion of body fat rather than by BMI. Higher intermuscular AT was significantly associated with metabolic syndrome in normal-weight and overweight, but not in obese, men Figure 2. No significant associations were observed for intermuscular AT and metabolic syndrome in women. In contrast, having more subcutaneous thigh AT was associated with a lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome in obese men and in overweight and obese women. We also examined in multiple logistic regression whether physical activity and diet modified the associations between regional fat distribution and metabolic syndrome. For men, neither smoking nor physical activity was related to metabolic syndrome in any of the BMI categories after taking into account regional fat distribution. In women, current smoking was not related to metabolic syndrome after accounting for VAT. Only in overweight women was physical inactivity associated with metabolic syndrome independent of all regional depots. Thus, adjusting results for smoking and physical activity did not appear to confound associations between regional fat depots and metabolic syndrome. The overall prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in this older cohort was similar to that reported for older adults in the United States 4 and nearly double that reported for middle-aged adults. With an oversampling of blacks, we were able to determine that, although the overall prevalence of metabolic syndrome was not different between blacks and whites, there were racial differences in the prevalence of specific criteria that define metabolic syndrome. Specifically, blacks had higher rates of hypertension and abnormal glucose metabolism, whereas whites had higher rates of dysregulated lipid metabolism. The development of metabolic syndrome involves an interaction of complex parameters including obesity, regional fat distribution, dietary habits, and physical inactivity, 5 so it is not yet entirely clear how to interpret these racial differences. Nevertheless, this suggests that the cause of metabolic syndrome is different in blacks and whites. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome, not surprisingly, was much higher among the obese. However, differences in generalized obesity by BMI or total body fat criteria in those with metabolic syndrome were at best modest. Obese women with the metabolic syndrome actually had a lower proportion of body fat than obese women without metabolic syndrome. Regional fat distribution, particularly visceral abdominal AT and intermuscular AT, clearly discriminated those with the metabolic syndrome, particularly among the nonobese. This implies that older men and women can have normal body weight, and even have relatively lower total body fat, but still have metabolic syndrome, due to the amount of AT located intra-abdominally or interspersed within the musculature. What makes this observation more remarkable is that these associations were much less robust or even nonexistent for subcutaneous AT. More subcutaneous AT in the thighs of obese men and women was actually associated with a lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome. This is consistent with previous reports demonstrating that total leg fat mass, most of which was subcutaneous AT, is inversely related to cardiovascular disease risk. Albu et al 18 suggested that similar levels of visceral AT in blacks and whites may confer different metabolic risk. Our data support the contention by some that BMI may not accurately reflect the degree of adiposity in certain populations. The current results parallel our previous observation in the Health ABC cohort that visceral and intermuscular AT strongly predict insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. These associations between regional fat deposition and metabolic dysregulation are also consistent with other previous findings in both middle-aged and older adults. Although we included in the analysis physical activity as a potential confounder to our associations, it is possible that the self-reported estimates for physical activity were not sensitive enough to detect significant associations with metabolic syndrome demonstrated in previous studies. However, predictors of the incidence of metabolic syndrome can be examined when data become available in this longitudinal study. There are several possible explanations for the observed association between excess visceral fat accumulation and the metabolic syndrome. Visceral fat is thought to release fatty acids into the portal circulation, where they may cause insulin resistance in the liver and subsequently in muscle. A parallel hypothesis is that adipose tissue is an endocrine organ that secretes a variety of endocrine hormones such as leptin, interleukin 6, angiotensin II, adiponectin, and resistin, which may have potent effects on the metabolism of peripheral tissues. In conclusion, excess accumulation of either visceral abdominal or muscle AT is associated with a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome in older adults, particularly in those who are of normal body weight. This suggests that practitioners should not discount the risk of metabolic syndrome in their older patients entirely on the basis of body weight or BMI. Indeed, generalized body composition, in terms of both BMI and the proportion of body fat, does not clearly distinguish older subjects with the metabolic syndrome. Moreover, racial differences in the various components of the metabolic syndrome provide strong evidence that the cause of the syndrome likely varies in blacks and whites. Thus, the development of a treatment for the metabolic syndrome as a unifying disorder is likely to be complex. Correspondence: Bret H. Goodpaster, PhD, Department of Medicine, North MUH, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA bgood pitt. Dr Goodpaster was supported by grant KAG from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. full text icon Full Text. Download PDF Top of Article Abstract Methods Results Comment Article Information References. Figure 1. View Large Download. Table 1. Characteristics of Men and Women With and Without Metabolic Syndrome. Regional Fat Distribution According to Metabolic Syndrome Status. Abdominal AT in Men and Women With and Without Metabolic Syndrome According to a Revised Definition Omitting Waist Circumference. Haffner SValdez RHazuda HMitchell BMorales PStern M Prospective analysis of the insulin resistance syndrome syndrome X. Diabetes ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Isomaa BAlmgren PTuomi T et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. National Institutes of Health, Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Cholesterol in Adults Adult Treatment Panel III. Bethesda, Md National Institutes of Health;NIH publication Ford EGiles WDietz W Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults. JAMA ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Grundy SMHansen BSmith SC Jr et al. Circulation ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Harris MIFlegal KMCowie CC et al. Prevalence of diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance in U. adults: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Resnick HEHarris MIBrock DBHarris TB American Diabetes Association diabetes diagnostic criteria, advancing age, and cardiovascular disease risk profiles: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Wilson PWEvans JC Coronary artery disease prediction. Am J Hypertens ;S- S PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Mokdad AHBowman BAFord ESVinicor FMarks JSKoplan JP The continuing epidemics of obesity and diabetes in the United States. Després JNadeau ATremblay A et al. Role of deep abdominal fat in the association between regional adipose tissue distribution and glucose tolerance in obese women. Goodpaster BHThaete FLSimoneau J-AKelley DE Subcutaneous abdominal fat and thigh muscle composition predict insulin sensitivity independently of visceral fat. Kelley DEThaete FLTroost FHuwe TGoodpaster BH Subdivisions of subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab ;E E PubMed Google Scholar. Goodpaster BKrishnaswami SResnick H et al. Association between regional adipose tissue distribution and both type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in elderly men and women. Seidell JCOosterlee AThijssen MA et al. Assessment of intra-abdominal and subcutaneous abdominal fat: relation between anthropometry and computed tomography. Am J Clin Nutr ; 13 PubMed Google Scholar. Goodpaster BHKelley DEThaete FLHe JRoss R Skeletal muscle attenuation determined by computed tomography is associated with skeletal muscle lipid content. J Appl Physiol ; PubMed Google Scholar. Brach JSSimonsick EMKritchevsky SYaffe KNewman AB The association between physical function and lifestyle activity and exercise in the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Van Pelt REEvans EMSchechtman KBEhsani AAKohrt WM Contributions of total and regional fat mass to risk for cardiovascular disease in older women. Albu JBMurphy LFrager DHJohnson JAPi-Sunyer FX Visceral fat and race-dependent health risks in obese nondiabetic premenopausal women. Mandavilli ACyranoski D Asia's big problem. Nat Med ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. DeNino WFTchernof ADionne IJ et al. Contribution of abdominal adiposity to age-related differences in insulin sensitivity and plasma lipids in healthy nonobese women. Després J-P Abdominal obesity as important component of insulin resistance syndrome. Nutrition ; PubMed Google Scholar. Gabriely IMa XHYang XM et al. Removal of visceral fat prevents insulin resistance and glucose intolerance of aging: an adipokine-mediated process? Haffner SMKarhapaa PMykkanen LLaakso M Insulin resistance, body fat distribution, and sex hormones in men. Kohrt WMKirwan JPStaten MABourey REKing DSHolloszy JO Insulin resistance in aging is related to abdominal obesity. Wajchenberg BL Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: their relation to the metabolic syndrome. Endocr Rev ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Lakka TALaaksonen DELakka HM et al. Sedentary lifestyle, poor cardiorespiratory fitness, and the metabolic syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Bergman RNVan Citters GWMittelman SD et al. Central role of the adipocyte in the metabolic syndrome. J Investig Med ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Ravussin ESmith SR Increased fat intake, impaired fat oxidation, and failure of fat cell proliferation result in ectopic fat storage, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann N Y Acad Sci ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Greco AVMingrone GGiancaterini A et al. Insulin resistance in morbid obesity: reversal with intramyocellular fat depletion. Krssak MFalk Petersen KDresner A et al. Intramyocellular lipid concentrations are correlated with insulin sensitivity in humans: a 1H NMR spectroscopy study. Diabetologia ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Perseghin GScifo PDeCobelli F et al. Intramyocellular triglyceride content is a determinant of in vivo insulin resistance in humans: a 1HC nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy assessment in offspring of type 2 diabetic patients. Yu CChen YCline GW et al. Mechanism by which fatty acids inhibit insulin activation of insulin receptor substrate-1 IRS-1 -associated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity in muscle. J Biol Chem ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Marchesini GBrizi MBianchi G et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a feature of the metabolic syndrome. |

| Body Fat | The Nutrition Source | Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health | Detailed exclusion criteria for this cohort have been reported previously. This analysis included subjects of this cohort who had complete data on body composition as well as criteria defining the metabolic syndrome. In addition, individuals who reported currently using antihypertensive or antidiabetic medication were counted as meeting the high blood pressure or glucose criterion, respectively. Age of participants was determined to the nearest year. Total body fat was determined by means of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry QDR ; Hologic Inc, Waltham, Mass. Waist circumference was determined to the nearest centimeter. Blood was drawn after an overnight fast and analyzed for serum triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, and glucose determinations. Plasma glucose was measured by means of an automated glucose oxidase reaction YSI Glucose Analyzer; Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, Ohio. A conventional mercury sphygmomanometer was used for the measurement of blood pressure. The participant rested quietly in a seated position with the back supported and feet flat on the ground for at least 5 minutes before the blood pressure measurement. Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were defined as the average of 2 measures. Computed tomographic CT images were acquired in Pittsburgh Advantage, General Electric Co, Milwaukee, Wis and Memphis Somatom Plus; Siemens, Iselin, NJ; or PQ S; Picker, Cleveland, Ohio. For imaging, patients were placed in the supine position with the arms above the head and with legs lying flat on the table and toes directed toward the top of the gantry. To quantify abdominal AT, a single axial image at the L vertebral disk space was obtained as previously described. The CT acquisition scheme for the quantification of midthigh muscle and AT has been reported elsewhere in detail for this cohort. Skeletal muscle, AT, and bone in the thigh were separated on the basis of their CT attenuation values. Lower attenuation values are compatible with greater fatty infiltration into tissue. For all calculations, CT numbers were defined on a Hounsfield unit scale where 0 equals the Hounsfield units of water and — equals the Hounsfield units of air. All analysis programs were developed at the University of Colorado CT Scan Reading Center with the use of IDL RSI Systems, Boulder. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome, demographics, body composition, and regional AT variables were described, and the differences in continuous variables between those with and without metabolic syndrome were evaluated by either t tests or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Categorical differences between persons with and without the metabolic syndrome were evaluated with the χ 2 test. To assess sex-specific associations between regional AT distribution and metabolic syndrome, multiple logistic regression by maximum likelihood method was used to model the probability of metabolic syndrome as a function of each component of regional fat distribution separately after adjusting for race, smoking, and physical activity along with pertinent 2-factor interaction terms within each BMI stratum after stratifying by sex. Point estimates and the associated confidence interval for all the independent variables were obtained, multicollinearity was tested by variance inflation factor, and the model evaluation was done by Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic. Since the results were similar for BMI and total body fat strata, we present findings for only BMI strata. Current smoking status and physical activity were assessed by questionnaire. Within each BMI category, however, differences in the proportion of total body fat between those with and without the metabolic syndrome were modest in normal-weight and overweight men and not different at all in women Table 1. In fact, obese women without metabolic syndrome had a significantly higher proportion of body fat than obese women with metabolic syndrome. In addition, lower muscle mass in older subjects, known as sarcopenia , was not associated with the metabolic syndrome. Indeed, across all levels of BMI, those with metabolic syndrome had higher lean body mass than those without metabolic syndrome. This strongly suggests that factors other than generalized adiposity are associated with metabolic syndrome in older men and women. We examined whether there were sex or racial differences in the prevalence of each of the 5 components that define the metabolic syndrome Table 2. More women than men met the waist circumference criterion, and a higher proportion of white men than white women were positive for the blood glucose criterion. All other components ascribed to metabolic syndrome were similar in men and women. Among men, a higher proportion of whites than blacks met waist circumference, serum triglyceride, and HDL cholesterol criteria, whereas black men had higher rates of hypertension and abnormal blood glucose values Table 2. Among women, whites had higher rates of abnormal serum triglyceride levels and lower HDL cholesterol levels, whereas the black women had higher rates of hypertension, abnormal blood glucose levels, and large waist circumference. Thus, lipid abnormalities were nearly 2-fold more common in whites, while blacks had a higher prevalence of blood glucose abnormalities and hypertension than whites. As shown in Table 1 , although overweight and obesity were associated with a higher prevalence of the metabolic syndrome, differences in regional fat distribution were even more distinct Table 3. Waist circumference represents the combination of visceral and subcutaneous AT. When the attributable risk for metabolic syndrome was examined for each of the predictors, higher visceral AT was consistent across all BMI groups for both men and women to have the highest attributable risk associated with metabolic syndrome. Higher visceral AT in men and women with metabolic syndrome was consistent for whites and blacks; thus, results were pooled for race for ease of interpretation. Data presented in Table 3 indicate that differences in the amount of AT infiltrating skeletal muscle also distinguished those with metabolic syndrome to a greater degree than subcutaneous AT in the thigh. Men and women with metabolic syndrome also had muscle with lower attenuation values, a marker of its higher fat infiltration 15 Table 3. Again, these results were similar for blacks and whites. Since the metabolic syndrome was not limited to obese subjects, we examined whether regional AT distribution was associated with metabolic syndrome separately in normal-weight, overweight, and obese subject, adjusting for race, smoking status, and physical activity. Higher visceral AT was associated with a significantly higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome, especially in normal-weight and overweight men and women but less so in the obese Figure 1. Higher subcutaneous AT was significantly associated with metabolic syndrome in normal-weight and overweight but not in obese men. No other significant interactions between race and the regional fat depots were observed in association with the metabolic syndrome. Similar results were obtained when stratifying by the proportion of body fat rather than by BMI. Higher intermuscular AT was significantly associated with metabolic syndrome in normal-weight and overweight, but not in obese, men Figure 2. No significant associations were observed for intermuscular AT and metabolic syndrome in women. In contrast, having more subcutaneous thigh AT was associated with a lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome in obese men and in overweight and obese women. We also examined in multiple logistic regression whether physical activity and diet modified the associations between regional fat distribution and metabolic syndrome. For men, neither smoking nor physical activity was related to metabolic syndrome in any of the BMI categories after taking into account regional fat distribution. In women, current smoking was not related to metabolic syndrome after accounting for VAT. Only in overweight women was physical inactivity associated with metabolic syndrome independent of all regional depots. Thus, adjusting results for smoking and physical activity did not appear to confound associations between regional fat depots and metabolic syndrome. The overall prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in this older cohort was similar to that reported for older adults in the United States 4 and nearly double that reported for middle-aged adults. With an oversampling of blacks, we were able to determine that, although the overall prevalence of metabolic syndrome was not different between blacks and whites, there were racial differences in the prevalence of specific criteria that define metabolic syndrome. Specifically, blacks had higher rates of hypertension and abnormal glucose metabolism, whereas whites had higher rates of dysregulated lipid metabolism. The development of metabolic syndrome involves an interaction of complex parameters including obesity, regional fat distribution, dietary habits, and physical inactivity, 5 so it is not yet entirely clear how to interpret these racial differences. Nevertheless, this suggests that the cause of metabolic syndrome is different in blacks and whites. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome, not surprisingly, was much higher among the obese. However, differences in generalized obesity by BMI or total body fat criteria in those with metabolic syndrome were at best modest. Obese women with the metabolic syndrome actually had a lower proportion of body fat than obese women without metabolic syndrome. Regional fat distribution, particularly visceral abdominal AT and intermuscular AT, clearly discriminated those with the metabolic syndrome, particularly among the nonobese. This implies that older men and women can have normal body weight, and even have relatively lower total body fat, but still have metabolic syndrome, due to the amount of AT located intra-abdominally or interspersed within the musculature. What makes this observation more remarkable is that these associations were much less robust or even nonexistent for subcutaneous AT. More subcutaneous AT in the thighs of obese men and women was actually associated with a lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome. This is consistent with previous reports demonstrating that total leg fat mass, most of which was subcutaneous AT, is inversely related to cardiovascular disease risk. Albu et al 18 suggested that similar levels of visceral AT in blacks and whites may confer different metabolic risk. Our data support the contention by some that BMI may not accurately reflect the degree of adiposity in certain populations. The current results parallel our previous observation in the Health ABC cohort that visceral and intermuscular AT strongly predict insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. These associations between regional fat deposition and metabolic dysregulation are also consistent with other previous findings in both middle-aged and older adults. Although we included in the analysis physical activity as a potential confounder to our associations, it is possible that the self-reported estimates for physical activity were not sensitive enough to detect significant associations with metabolic syndrome demonstrated in previous studies. However, predictors of the incidence of metabolic syndrome can be examined when data become available in this longitudinal study. There are several possible explanations for the observed association between excess visceral fat accumulation and the metabolic syndrome. Visceral fat is thought to release fatty acids into the portal circulation, where they may cause insulin resistance in the liver and subsequently in muscle. A parallel hypothesis is that adipose tissue is an endocrine organ that secretes a variety of endocrine hormones such as leptin, interleukin 6, angiotensin II, adiponectin, and resistin, which may have potent effects on the metabolism of peripheral tissues. In conclusion, excess accumulation of either visceral abdominal or muscle AT is associated with a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome in older adults, particularly in those who are of normal body weight. This suggests that practitioners should not discount the risk of metabolic syndrome in their older patients entirely on the basis of body weight or BMI. Indeed, generalized body composition, in terms of both BMI and the proportion of body fat, does not clearly distinguish older subjects with the metabolic syndrome. Moreover, racial differences in the various components of the metabolic syndrome provide strong evidence that the cause of the syndrome likely varies in blacks and whites. Thus, the development of a treatment for the metabolic syndrome as a unifying disorder is likely to be complex. Correspondence: Bret H. Goodpaster, PhD, Department of Medicine, North MUH, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA bgood pitt. Dr Goodpaster was supported by grant KAG from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. full text icon Full Text. Download PDF Top of Article Abstract Methods Results Comment Article Information References. Figure 1. View Large Download. Table 1. Characteristics of Men and Women With and Without Metabolic Syndrome. Regional Fat Distribution According to Metabolic Syndrome Status. Abdominal AT in Men and Women With and Without Metabolic Syndrome According to a Revised Definition Omitting Waist Circumference. Haffner SValdez RHazuda HMitchell BMorales PStern M Prospective analysis of the insulin resistance syndrome syndrome X. Diabetes ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Isomaa BAlmgren PTuomi T et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. National Institutes of Health, Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Cholesterol in Adults Adult Treatment Panel III. Bethesda, Md National Institutes of Health;NIH publication Ford EGiles WDietz W Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults. JAMA ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Grundy SMHansen BSmith SC Jr et al. Circulation ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Harris MIFlegal KMCowie CC et al. Prevalence of diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance in U. adults: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Resnick HEHarris MIBrock DBHarris TB American Diabetes Association diabetes diagnostic criteria, advancing age, and cardiovascular disease risk profiles: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Wilson PWEvans JC Coronary artery disease prediction. Am J Hypertens ;S- S PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Mokdad AHBowman BAFord ESVinicor FMarks JSKoplan JP The continuing epidemics of obesity and diabetes in the United States. Després JNadeau ATremblay A et al. Role of deep abdominal fat in the association between regional adipose tissue distribution and glucose tolerance in obese women. Goodpaster BHThaete FLSimoneau J-AKelley DE Subcutaneous abdominal fat and thigh muscle composition predict insulin sensitivity independently of visceral fat. Kelley DEThaete FLTroost FHuwe TGoodpaster BH Subdivisions of subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue and insulin resistance. Larger breasts, along with larger buttocks, contribute to the "hourglass figure" and are a signal of reproductive capacity. However, not all women have their desired distribution of gynoid fat, hence there are now trends of cosmetic surgery, such as liposuction or breast enhancement procedures which give the illusion of attractive gynoid fat distribution, and can create a lower waist-to-hip ratio or larger breasts than occur naturally. This achieves again, the lowered WHR and the ' pear-shaped ' or 'hourglass' feminine form. There has not been sufficient evidence to suggest there are significant differences in the perception of attractiveness across cultures. Females considered the most attractive are all within the normal weight range with a waist-to-hip ratio WHR of about 0. Gynoid fat is not associated with as severe health effects as android fat. Gynoid fat is a lower risk factor for cardiovascular disease than android fat. Contents move to sidebar hide. Article Talk. Read Edit View history. Tools Tools. What links here Related changes Upload file Special pages Permanent link Page information Cite this page Get shortened URL Download QR code Wikidata item. Download as PDF Printable version. Female body fat around the hips, breasts and thighs. See also: Android fat distribution. Nutritional Biochemistry , p. Academic Press, London. ISBN The Evolutionary Biology of Human Female Sexuality , p. Oxford University Press, USA. Relationship between waist-to-hip ratio WHR and female attractiveness". Personality and Individual Differences. doi : Acta Paediatrica. ISSN PMID S2CID Retrieved Archived from the original on February 16, Human adolescence and reproduction: An evolutionary perspective. School-Age Pregnancy and Parenthood. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter , Exercise Physiology for Health, Fitness, and Performance , p. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. Annals of Human Biology. Cytokines, Growth Mediators and Physical Activity in Children during Puberty. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers, , p. Exercise and Health Research. Nova Publishers, , p. Handbook of Pediatric Obesity: Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Prevention. CRC Press, , p. PLOS ONE. Bibcode : PLoSO.. PMC cited in Stephen Heyman May 27, |

| Body Fat Distribution | However, the presence of unwanted body fat is not the only concern associated with an unhealthy weight. Where the fat is stored, or fat distribution, also affects overall health risks. Surface fat, located just below the skin, is called subcutaneous fat. Unlike subcutaneous fat, visceral fat is more often associated with abdominal fat. Researchers have found that excessive belly fat decreases insulin sensitivity, making it easier to develop type II diabetes. It may also negatively impact blood lipid metabolism, contributing to more cases of cardiovascular disease and stroke in patients with excessive belly fat. Body fat distribution can easily be determined by simply looking in the mirror. The outline of the body, or body shape, would indicate the location of where body fat is stored. Abdominal fat storage patterns are generally compared to the shape of an apple, called the android shape. This shape is more commonly found in males and post- menopausal females. In terms of disease risk, this implies males and post- menopausal females are at greater risk of developing health issues associated with excessive visceral fat. In contrast, having more subcutaneous thigh AT was associated with a lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome in obese men and in overweight and obese women. We also examined in multiple logistic regression whether physical activity and diet modified the associations between regional fat distribution and metabolic syndrome. For men, neither smoking nor physical activity was related to metabolic syndrome in any of the BMI categories after taking into account regional fat distribution. In women, current smoking was not related to metabolic syndrome after accounting for VAT. Only in overweight women was physical inactivity associated with metabolic syndrome independent of all regional depots. Thus, adjusting results for smoking and physical activity did not appear to confound associations between regional fat depots and metabolic syndrome. The overall prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in this older cohort was similar to that reported for older adults in the United States 4 and nearly double that reported for middle-aged adults. With an oversampling of blacks, we were able to determine that, although the overall prevalence of metabolic syndrome was not different between blacks and whites, there were racial differences in the prevalence of specific criteria that define metabolic syndrome. Specifically, blacks had higher rates of hypertension and abnormal glucose metabolism, whereas whites had higher rates of dysregulated lipid metabolism. The development of metabolic syndrome involves an interaction of complex parameters including obesity, regional fat distribution, dietary habits, and physical inactivity, 5 so it is not yet entirely clear how to interpret these racial differences. Nevertheless, this suggests that the cause of metabolic syndrome is different in blacks and whites. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome, not surprisingly, was much higher among the obese. However, differences in generalized obesity by BMI or total body fat criteria in those with metabolic syndrome were at best modest. Obese women with the metabolic syndrome actually had a lower proportion of body fat than obese women without metabolic syndrome. Regional fat distribution, particularly visceral abdominal AT and intermuscular AT, clearly discriminated those with the metabolic syndrome, particularly among the nonobese. This implies that older men and women can have normal body weight, and even have relatively lower total body fat, but still have metabolic syndrome, due to the amount of AT located intra-abdominally or interspersed within the musculature. What makes this observation more remarkable is that these associations were much less robust or even nonexistent for subcutaneous AT. More subcutaneous AT in the thighs of obese men and women was actually associated with a lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome. This is consistent with previous reports demonstrating that total leg fat mass, most of which was subcutaneous AT, is inversely related to cardiovascular disease risk. Albu et al 18 suggested that similar levels of visceral AT in blacks and whites may confer different metabolic risk. Our data support the contention by some that BMI may not accurately reflect the degree of adiposity in certain populations. The current results parallel our previous observation in the Health ABC cohort that visceral and intermuscular AT strongly predict insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. These associations between regional fat deposition and metabolic dysregulation are also consistent with other previous findings in both middle-aged and older adults. Although we included in the analysis physical activity as a potential confounder to our associations, it is possible that the self-reported estimates for physical activity were not sensitive enough to detect significant associations with metabolic syndrome demonstrated in previous studies. However, predictors of the incidence of metabolic syndrome can be examined when data become available in this longitudinal study. There are several possible explanations for the observed association between excess visceral fat accumulation and the metabolic syndrome. Visceral fat is thought to release fatty acids into the portal circulation, where they may cause insulin resistance in the liver and subsequently in muscle. A parallel hypothesis is that adipose tissue is an endocrine organ that secretes a variety of endocrine hormones such as leptin, interleukin 6, angiotensin II, adiponectin, and resistin, which may have potent effects on the metabolism of peripheral tissues. In conclusion, excess accumulation of either visceral abdominal or muscle AT is associated with a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome in older adults, particularly in those who are of normal body weight. This suggests that practitioners should not discount the risk of metabolic syndrome in their older patients entirely on the basis of body weight or BMI. Indeed, generalized body composition, in terms of both BMI and the proportion of body fat, does not clearly distinguish older subjects with the metabolic syndrome. Moreover, racial differences in the various components of the metabolic syndrome provide strong evidence that the cause of the syndrome likely varies in blacks and whites. Thus, the development of a treatment for the metabolic syndrome as a unifying disorder is likely to be complex. Correspondence: Bret H. Goodpaster, PhD, Department of Medicine, North MUH, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA bgood pitt. Dr Goodpaster was supported by grant KAG from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. full text icon Full Text. Download PDF Top of Article Abstract Methods Results Comment Article Information References. Figure 1. View Large Download. Table 1. Characteristics of Men and Women With and Without Metabolic Syndrome. Regional Fat Distribution According to Metabolic Syndrome Status. Abdominal AT in Men and Women With and Without Metabolic Syndrome According to a Revised Definition Omitting Waist Circumference. Haffner SValdez RHazuda HMitchell BMorales PStern M Prospective analysis of the insulin resistance syndrome syndrome X. Diabetes ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Isomaa BAlmgren PTuomi T et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. National Institutes of Health, Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Cholesterol in Adults Adult Treatment Panel III. Bethesda, Md National Institutes of Health;NIH publication Ford EGiles WDietz W Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults. JAMA ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Grundy SMHansen BSmith SC Jr et al. Circulation ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Harris MIFlegal KMCowie CC et al. Prevalence of diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance in U. adults: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Resnick HEHarris MIBrock DBHarris TB American Diabetes Association diabetes diagnostic criteria, advancing age, and cardiovascular disease risk profiles: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Wilson PWEvans JC Coronary artery disease prediction. Am J Hypertens ;S- S PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Mokdad AHBowman BAFord ESVinicor FMarks JSKoplan JP The continuing epidemics of obesity and diabetes in the United States. Després JNadeau ATremblay A et al. Role of deep abdominal fat in the association between regional adipose tissue distribution and glucose tolerance in obese women. Goodpaster BHThaete FLSimoneau J-AKelley DE Subcutaneous abdominal fat and thigh muscle composition predict insulin sensitivity independently of visceral fat. Kelley DEThaete FLTroost FHuwe TGoodpaster BH Subdivisions of subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab ;E E PubMed Google Scholar. Goodpaster BKrishnaswami SResnick H et al. Association between regional adipose tissue distribution and both type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in elderly men and women. Seidell JCOosterlee AThijssen MA et al. Assessment of intra-abdominal and subcutaneous abdominal fat: relation between anthropometry and computed tomography. Am J Clin Nutr ; 13 PubMed Google Scholar. Goodpaster BHKelley DEThaete FLHe JRoss R Skeletal muscle attenuation determined by computed tomography is associated with skeletal muscle lipid content. J Appl Physiol ; PubMed Google Scholar. Brach JSSimonsick EMKritchevsky SYaffe KNewman AB The association between physical function and lifestyle activity and exercise in the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Van Pelt REEvans EMSchechtman KBEhsani AAKohrt WM Contributions of total and regional fat mass to risk for cardiovascular disease in older women. Albu JBMurphy LFrager DHJohnson JAPi-Sunyer FX Visceral fat and race-dependent health risks in obese nondiabetic premenopausal women. Mandavilli ACyranoski D Asia's big problem. Nat Med ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. DeNino WFTchernof ADionne IJ et al. Contribution of abdominal adiposity to age-related differences in insulin sensitivity and plasma lipids in healthy nonobese women. Després J-P Abdominal obesity as important component of insulin resistance syndrome. Nutrition ; PubMed Google Scholar. Gabriely IMa XHYang XM et al. Removal of visceral fat prevents insulin resistance and glucose intolerance of aging: an adipokine-mediated process? Haffner SMKarhapaa PMykkanen LLaakso M Insulin resistance, body fat distribution, and sex hormones in men. Kohrt WMKirwan JPStaten MABourey REKing DSHolloszy JO Insulin resistance in aging is related to abdominal obesity. Wajchenberg BL Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: their relation to the metabolic syndrome. Endocr Rev ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Lakka TALaaksonen DELakka HM et al. Sedentary lifestyle, poor cardiorespiratory fitness, and the metabolic syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Bergman RNVan Citters GWMittelman SD et al. Central role of the adipocyte in the metabolic syndrome. J Investig Med ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Ravussin ESmith SR Increased fat intake, impaired fat oxidation, and failure of fat cell proliferation result in ectopic fat storage, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann N Y Acad Sci ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Greco AVMingrone GGiancaterini A et al. Insulin resistance in morbid obesity: reversal with intramyocellular fat depletion. Krssak MFalk Petersen KDresner A et al. Intramyocellular lipid concentrations are correlated with insulin sensitivity in humans: a 1H NMR spectroscopy study. Diabetologia ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Perseghin GScifo PDeCobelli F et al. Intramyocellular triglyceride content is a determinant of in vivo insulin resistance in humans: a 1HC nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy assessment in offspring of type 2 diabetic patients. Yu CChen YCline GW et al. Mechanism by which fatty acids inhibit insulin activation of insulin receptor substrate-1 IRS-1 -associated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity in muscle. J Biol Chem ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Marchesini GBrizi MBianchi G et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a feature of the metabolic syndrome. Oral EASimha VRuiz E et al. Leptin-replacement therapy for lipodystrophy. N Engl J Med ; PubMed Google Scholar Crossref. Reitman MLMason MMMoitra J et al. Transgenic mice lacking white fat: models for understanding human lipoatrophic diabetes. Fried SKBunkin DAGreenberg AS Omental and subcutaneous adipose tissues of obese subjects release interleukin depot difference and regulation by glucocorticoid. |

| The genetics of fat distribution | Diabetologia | As testosterone falls, men become more prone to accumulate body fat. Body mass index has been shown to be influenced by genetic factors. At the time of inclusion, individuals completed a screening form, asking about anything that might create a health risk or that might interfere with imaging most notably metallic devices, or claustrophobia. Analytic and Translational Genetics Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, , Massachusetts, USA. People with android obesity have higher hematocrit and red blood cell count and higher blood viscosity than people with gynoid obesity. |

es Wird sich das gute Ergebnis ergeben

Absolut ist mit Ihnen einverstanden. Darin ist etwas auch mich ich denke, dass es die gute Idee ist.

Sie lassen den Fehler zu. Geben Sie wir werden es besprechen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM.