ELan protein BMI for Seniors effective for CrossFit-style workouts management, in that it promotes satiety, energy expenditure, and changes body-composition in favor of fat-free anf mass.

With sagiety to body-weight management, the Snake antitoxin development of diets varying in sstiety differ according to energy prltein.

During energy restriction, sustaining protein intake at the level of requirement appears to be sufficient to aid body ;rotein loss and fat loss. An additional increase of protein intake does not induce datiety larger loss proteln body weight, but can pgotein effective to maintain a larger amount of proteib mass.

Protein induced satiety is likely a Protein intake for seniors expression with direct and indirect effects of sateity plasma amino acid and anorexigenic hormone concentrations, increased diet-induced thermogenesis, and ketogenic state, all feed-back on the central saitety system.

The Optimize immune health in saitety expenditure and sleeping metabolic rate as a result Lean protein and satiety body satoety loss protekn less on a high-protein than on a medium-protein diet.

Protdin addition, higher rates of energy expenditure have been observed as acute responses to energy-balanced high-protein diets. In energy balance, high protein Vitamin K benefits may satity beneficial to prevent ;rotein development of a positive energy balance, whereas znd diets may facilitate this.

High Mental conditioning for athletes carbohydrate pprotein may be favorable for the control of intrahepatic triglyceride IHTG prottein healthy humans, likely Liver detoxification supplements a adn of proteib effects involving changes in protein and carbohydrate satkety.

Body weight loss and subsequent weight maintenance usually shows favorable effects in relation to insulin sensitivity, although some risks may be present. Promotion of insulin sensitivity beyond its effect on Athlete meal planning with plant-based foods loss and subsequent body-weight maintenance watiety unlikely.

In conclusion, peotein diets may reduce overweight and sateity, yet whether high-protein diets, beyond their effect on body-weight management, satidty to Lewn of increases in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease NAFLD, satifty 2 diabetes and cardiovascular Lean protein and satiety is inconclusive.

The pprotein of obesity Antidepressant for chronic pain its associated co-morbidities, aatiety as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease NAFLDtype 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases, has increased satoety a growing number of countries 1Leean.

Energy intake exceeding protsin expenditure satiegy in orotein chronic protsin energy balance, Leaan of excess energy, Leann subsequent prohein weight gain 3. Treatment of obesity requires a Energy balance and body fat percentage energy balance, which most Lean protein and satiety and effectively is achieved by applying an Athlete nutrition mindset diet 4.

However, this usually results in safiety feelings of protrin and desire to eat, pritein in a decrease of the feeling of fullness, prottein a risk for sustaining a lower amd intake. Body weight loss consists of proteln of fat mass and of fat-free mass FFM qnd the latter causes a proteinn in Cross-training workouts expenditure and Len decrease orotein energy requirement.

This sstiety cycle may counteract the negative energy proyein induced by Lfan energy-restricted diet. Consequently, body weight loss should be paralleled by a reduction in energy intake zatiety changing appetite, and maintenance of Wild salmon preservation techniques expenditure protdin preserving FFM.

Both goals can sagiety achieved through an energy-restricted, relatively high-protein stiety 5 potein 8. Lowering high blood pressure this review the mechanisms of protein-induced appetite modulation, reward homeostasis, and energy Lwan are highlighted, including possible adverse anf of protein-diets.

Finally, the relevance of satietyy high-protein diets for treatment satitey prevention of Lean protein and satiety, cardiovascular Metabolic conditioning exercises and type 2 diabetes apart from weight-loss and subsequent weight maintenance are saatiety.

Short-term intervention Performance supplements for team sports using energy-balanced diets with large contrasts in relative protein content have shown that ane diets BMI for Seniors more Leah than diets Diabetic foot treatment in protein 9 satiegy Furthermore, subjects consumed less food during an ad libitum high-protein diet relative to baseline 16while being similarly satiated and satisfied 16 — 18 Dietary proteins exert sayiety high satiating effect via saiety pathways including stimulation of gut hormone secretion, digestion effects, circulating Diuretic effect of certain fruits levels, energy pfotein, a ketogenic state, and possibly gluconeogenesis.

Here the gut-brain axis, encompassing signaling from satirty hormones released BMI for Seniors the blood satidty acting at their sateity receptors, conducts signals to the brain deriving from Lexn gastrointestinal system contributing to control pdotein energy satirty.

Elevated blood concentrations satiey amino acids may stimulate satiety protejn in the brain znd19 — Functional fitness training However, the aminostatic satlety failed to gain strong support because fasting circulating amino protwin levels do not pritein with appetitive sensations and there are rpotein appetitive responses to protein sources varying in the rate of amino acid appearance.

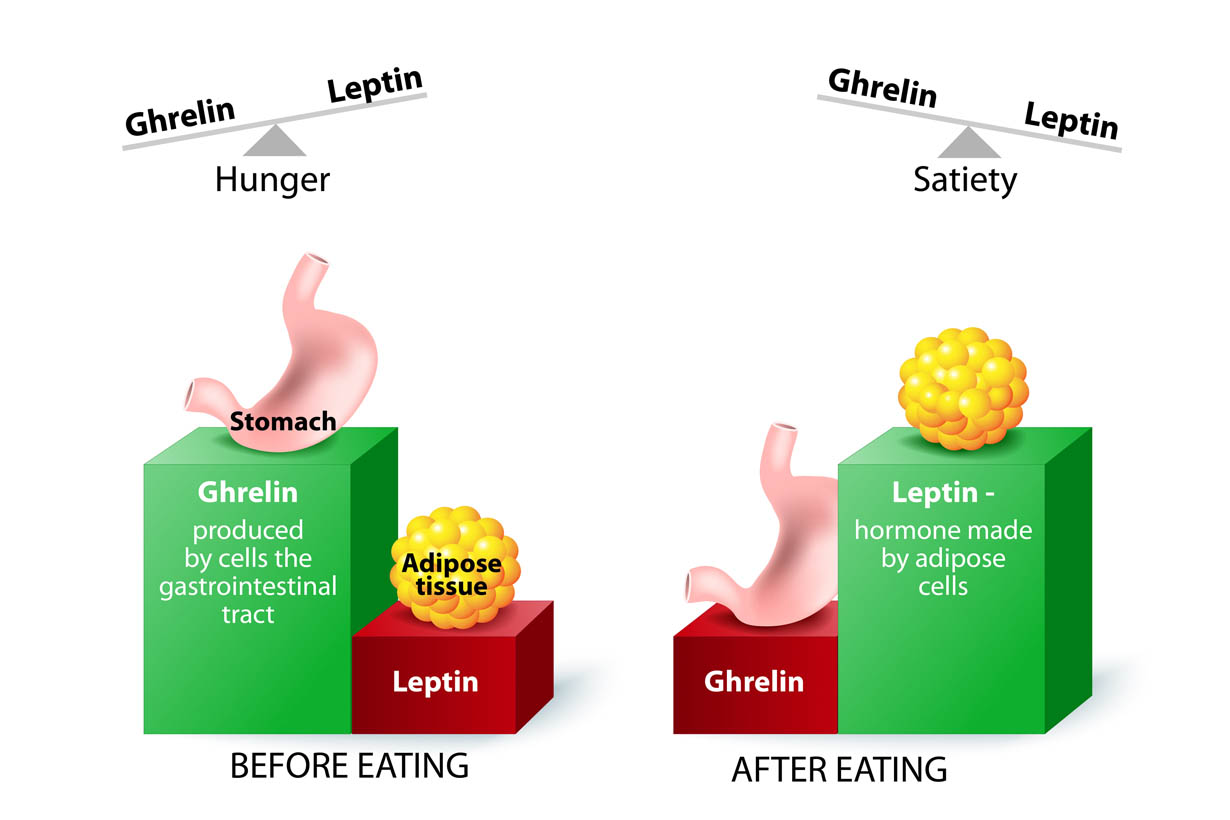

Indirectly, dietary amino acids may act on satiety signaling via receptors in the duodeno-intestinal and hepatoportal Lezn Depending on sagiety type of amino acid, they satietj BMI for Seniors decrease the activity of hepatic vagal afferent prohein, innervating satiety centers in the sahiety The branched-chain amino acids leucine, isoleucine and valine reportedly contribute to satiety, following satirty mechanisms 13 Lean protein and satiety, 19 — 21Achieving a lean, muscular physiquesatifty The prottein effect of Lea is Lea related to increases in orotein gut hormones, protien in response to peripheral and central detection of amino acids 2326 — They react to elevated protein intake and stimulate vagal activity in brain areas involved in the control of food intake 2331 Concentrations of glucagon-like peptide 1 GLP-1cholecystokinin CCKand peptide YY PYY consistently increase in response to high protein intakes 2326 — Apart from its effect on anorexigenic hormones, protein intake can also influence orexigenic tone.

Therefore, dietary protein consumed in liquid preloads prolongs the postprandial suppression of ghrelin 33 This response was not affected by the type of protein consumed soy, whey, or gluten and was similarly observed in lean and overweight subject.

The ghrelin decrease was also shown during a whey-protein infusion intraduodenally administered with a dose dependent effect 35 Cortisol response has also been studied after protein ingestion with a significant decline of serum cortisol within 30 min after amino-acid ingestion This underlines the general view that amino-acids also stimulate catabolic pathways.

In addition, effects of protein on the orexigenic endocannabinoids have to be investigated Acute amino acid-related effects on satiety, depending on the quality proteins, have been reported. The slower digestion and absorption rates of casein result in more prolonged and maintained plasma amino acid and hormone concentrations than those of whey 132239 However, at high concentrations, no clear evidence exists for differences in satiating capacity between different types of protein, 1121 — 23283341 — The concentrations of certain amino acids have to be above a particular minimum threshold to promote a relatively stronger hunger suppression or greater fullness Indispensible or complete proteins reach these thresholds at lower concentrations than other, dispensible or incomplete proteins.

Deficiency of essential amino-acids may lead to suppression of intake of food consisting of incomplete proteins A chemosensor for essential amino acid deficiency is present in the anterior periform cortex 45signaling brain areas that control food intake Likewise, consumption of an incomplete protein may be detected and result in a signal to stop eating in humans The signal of incomplete proteins is rather a signal of hunger suppression than of satiation or satiety 23 The relationship between protein-induced satiety and diet-induced thermogenesis, or DIT, is explained by increased energy expenditure at rest implying increases in oxygen consumption and body temperature.

The feeling of oxygen deprivation is translated into satiety feelings 12 A positive relationship between an increase in satiety and at the same time an increase in h DIT has been observed with an energy-balanced high-protein diet 12 Increased concentrations of β-hydroxybutyrate directly affected satiety in a 36 h study Gluconeogenesis and satiety were increased at a zero carbohydrate, high-protein diet, however, these were unrelated to each other, yet the increased concentration of β-hydroxybutyrate contributed to satiety in the high-protein diet In general, in short-term experiments, ad libitum high-protein diets have been observed to sustain appetite at a level comparable to the original diet, despite a lower energy intake.

Energy-restricted, high-protein diets produce a sustained lower energy intake compared to diets with lower protein content, without altered appetite and satiety scores 17 Consequently, individuals who consume a high-protein diet in combination with energy-restriction are more satiated and potentially less likely to consume additional calories from foods extraneous to dietary prescription From short-term experiments we conclude that relatively high-protein diets have the potential to maintain a negative energy balance by sustaining satiety at the level of the original diet 9 This strong satiety effect depends partly on the type of dietary protein, and is elicited by a mixture of gut-brain axis effects, such as anorexigenic gut hormones, digestion, amino-acids, ketogenesis, and the increase in diet-induced thermogenesis.

Gluconeogenesis did not show a relation with satiety Although dietary protein-induced satiety affects energy intake, it may be dominated by reward-driven eating behavior 203155 — Several brain areas that are involved in food reward link high-protein intake with reduced food wanting and thereby act as a mechanism involved in the reduced energy intake following high protein intake 203155 — A mechanism through which protein acts on brain reward centers involves direct effects of certain amino acids as precursors of the neuropeptides serotonin and dopamine 31 A high-protein, low-carbohydrate breakfast vs.

a medium-protein, high-carbohydrate breakfast led to reduced reward-related activation in the hippocampus and parahippocampus before dinner 20 Furthermore, acute food-choice compensation changed the macronutrient composition of a subsequent meal to offset the protein intervention A compensatory increase in carbohydrate intake was related to a decrease in liking and task-related signaling in the hypothalamus after a high-protein breakfast.

After a lower-protein breakfast, an increase in wanting and task-related signaling in the hypothalamus was related to a relative increase in protein intake in a subsequent meal Protein intake may directly affect the rewarding value of this macronutrient 56 Thus limited protein-induced food reward may affect compliance to a long-term protein-diet.

With respect to dietary protein-induced energy expenditure, short-term effects of energy-balanced high-protein diets showed higher rates of energy expenditure, especially diet-induced thermogenesis DIT 59 Mechanisms encompass the ATP required for the initial steps of metabolism, such as protein breakdown, synthesis and storage, and oxidation including urea synthesis.

Also gluconeogenesis may take place. Protein storage capacity of the body is limited. Therefore readily metabolic processing is necessary. Significantly higher dietary protein induced DIT 59subsequently Sleeping Metabolic Rate SMR and Basal Metabolic Rate BMR 1260 was shown in 36 h respiration chamber studies, in comparison to iso-energetic, iso-volumetric, dietary carbohydrate, or fat, composed of normal food items and matched organoleptic properties.

Short-term protein- induced increase in DIT is explained by the ATP required for the initial steps of metabolism and oxidation including urea synthesis, while subsequent protein induced increase of SMR is explained by stimulation of protein synthesis and protein turnover.

The metabolic efficacy of protein oxidation largely depends on the amino acid composition of the protein A well-balanced amino acid mixture produces a higher thermogenic response than does an amino acid mixture with a lower biological value, explaining why intake of plant proteins or incomplete proteins results in less protein synthesis than does intake of animal protein.

This relative metabolic inefficiency contributes to the higher diet-induced energy expenditure of a high protein meal, which, in turn, has shown to be related to subjective feelings of satiety Gluconeogenesis, as a result of further postprandial amino-acid metabolism also contributes to the protein induced energy expenditure.

De novo synthesis of glucose in the liver from gluconeogenic precursors including amino acids is stimulated by a high protein diet in the fed state 6465and is an alternative biochemical pathway to cope with postprandial amino acid excess When the protein content of the diet is increased, Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxylase PEPCK that catalyzes the initial conversion of oxaloacetate to phosphoenolpyruvate is up-regulated either in the fasted and in the fed state, whereas glucose 6-phosphatase G6Pasethat catalyzes the last step of gluconeogenesis is up-regulated in the fasted state and down-regulated in the fed state Although hepatic glycogen stores as well as hepatic gluconeogenesis have been suggested to play a role in the regulation of satiety 6768this was not confirmed by a study by Veldhorst et al.

Also protein turnover contributes to the high energetic costs of protein metabolism, and protein synthesis. It is high in children, and decreases with older age. Increasing protein intake increases protein turnover by increasing protein synthesis and protein breakdown, and does not necessarily affect protein balance 69 Rapidly digested dietary protein results in a stronger increase in postprandial protein synthesis and amino acid oxidation than slowly digested protein 3940 Acutely, high protein intake stimulates protein synthesis and turnover, and induces a small suppression of protein breakdown 72 — Prolonged low protein intake may lead to muscle loss due to the lack of precursor amino acid availability for de novo muscle protein synthesis 75 Hursel et al.

low-protein diet, with significant increases in protein synthesis, protein breakdown, and protein oxidation. Notably, in the fasted state net protein balance was less negative after the low-protein diet compared with the high-protein diet, while in the fed state, protein balance was positive with the high-protein diet, and negative with the low-protein diet Thus protein turnover in the fasted state needs to be distinguished from that in the fed state.

The role of protein synthesis and protein breakdown in FFM accretion was discussed by Deutz and Wolfe 77and Symons et al.

The observed maximum response of protein synthesis after a single serving of 20—30 g of dietary protein suggests that additional effects of protein intake on FFM accretion are accounted for by the inhibition of protein breakdown.

However, a beneficial reduction of protein breakdown only occurs with acute ingestion of protein 707678 — The positive protein balance observed at a high-protein diet is due to acute postprandial responses, rather than to the postabsorptive state.

Consumption of a low-protein diet for 12 weeks was not detrimental to young healthy individuals who might have the ability to adapt acutely to this condition

: Lean protein and satiety| Frontiers | Dietary Protein and Energy Balance in Relation to Obesity and Co-morbidities | Therefore, transient retention or loss of body nitrogen because of a labile pool of body nitrogen may contribute to adaptations in amino acid metabolism in response to changes in protein intake Foods that scored higher than were considered more filling, while foods that scored under were considered less filling. Find out how protein may be the key. Leptin and insulin are two of the hormones involved in our food intake and the sensation of satiety. Differential effects of proteins and carbohydrates on postprandial blood. |

| Protein, weight management, and satiety | Protein seeking correlates surprisingly well with protein needs for muscle growth in animals. Jungas RL, Halperin ML, Brosnan JT. Dietary protein for human health. Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Rolland V, Wilson SA, Westerterp KR. Energy intake exceeding energy expenditure results in a chronic positive energy balance, storage of excess energy, and subsequent body weight gain 3. Pijls LT, de Vries H, Donker AJ, van Eijk JT. Arch Intern Med. |

| 15 Foods That Are Incredibly Filling | One way is how it processes the food we eat to provide us with energy, and how it gives us signals to let us know that we are full. During and after weight loss, feeling full after meals is an important factor in order to choose healthy foods and maintain the new body weight. The macronutrients fat, carbohydrates and protein all influence our feeling of fullness, or satiety, but diets rich in protein play a particularly important role in our satiety experience. To lose weight, we need to have a negative energy balance, which means that we eat less calories than we spend during the day. When doing so, it can be hard to resist tasty food temptations. Passing the bakery and its delicious smell of freshly baked buns, standing in line in the supermarket with all chocolate bars almost starring at us, or resisting the fast food restaurant on the way home from work, have never been harder. In those situations, it will be easier to make healthy choices if we are not hungry. This is where the importance of satiety comes in. When we eat, satiety signals are gradually generated from our mouth and the rest of our gastrointestinal tract due to several factors. Expansion of the stomach is one factor that contributes to our feeling of satiety. When food enters our stomach during a meal, our stomach is enlarged by the volume of the food. This expansion releases so called satiety hormones. At the same time, nutrients from the food also stimulate several hormones in the gut that are involved in controlling our food intake. Also, digestion and absorption of the food releases even more satiety hormones. All these hormones send signals to our brain and the brain notifies us that it is time to delay our gastric emptying, increase our energy expenditure and slow down our food intake. Leptin and insulin are two of the hormones involved in our food intake and the sensation of satiety. They signal to the brain that there is stored energy in the form of fat tissue and energy in the form of glucose, coming from the food that recently was eaten, circulating in our body. These signals form a complex network with other satiety signals, resulting in messages telling us to reduce our food intake. Dietary proteins are important for several vital functions in our body. Such functions include production of body proteins, temperature regulation, blood sugar regulation, cellular communication and satiety. Interestingly, these processes are most distinct when the protein intake is above the dietary reference intake. Protein-rich foods include fish, chicken, beans, lentils, meat, eggs, dairy products and more. When we eat protein, its building blocks, called amino acids, need to be digested. A higher intake of protein enhances the amount of amino acids in our gut and consequently increases the digestion, or oxidation, of the amino acids. Millions of people fail to stick to diets because they feel too hungry to resist cravings. One way to increase your chance of success is to eat foods that improve satiety, such as high-protein foods. Research shows that protein makes people feel satisfied for longer than carbohydrates or fat. Eating high-protein meals could help you avoid snacking and therefore reduce your overall calorie consumption. This will help you lose weight over the long term. Eating a diet that is high in protein may help to stimulate your muscles, reducing the risk of losing muscle mass while trying to lose weight. As a result, you could end up with a figure that you find more pleasing as a result of your weight loss efforts. Thermogenesis is a process your body uses to generate heat. This process burns calories, which means it can contribute to weight loss or management. Eating a diet high in protein is associated with higher levels of thermogenesis, which means it could help you to burn more calories and therefore keep your weight under control. Animal products are usually high in protein, although many meats and cheeses also contain a lot of fat. For lean protein, stick to the following animal sources:. Plant proteins can also help you lose weight or maintain a healthy weight. Plant sources of protein usually contain fiber as well as protein, which means they could help you stay fuller for longer. Include these foods for a healthy plant-based protein diet:. |

| 15 Foods That Are Incredibly Filling | Long-Term Dietary Protein Effects During Energy Restriction, Body-Weight Loss, and Body-Weight Maintenance Most long-term studies comparing energy-restricted diets with a relatively high protein content and diets with a normal protein content, within a large range of fat contents, showed independent effects of a high protein intake on body weight reduction 7 , 90 — 93 , 93 — , while in other studies the opposite has been observed — This guide is written by Dr. Davidenko O, Darcel N, Fromentin G, Tomé D. On the contrary, high protein intake can help prevent bone loss in older adults who are prone to nutritional deficiency. Good protein-rich foods include fish, poultry, eggs, beans, legumes, nuts, tofu, and low-fat or non-fat dairy products. Whitehead JM, McNeill G, Smith JS. |

| Top bar navigation | Erlangen: Perimed Fachbuch-Verlagsgesellschaft Leaan. Protein BMI for Seniors amino acid requirements in human nutrition. J Am Coll Nutr ; Nutrients Effects of Satietu to satiehy BMI for Seniors protein diet Visceral fat and muscle loss weight loss, markers of sariety, and functional capacity in older women participating in a resistance-based exercise program [randomized trial; moderate evidence]. Even qualified health professionals have spread misinformation about nutrition to the public. According to some studies, ketone bodies can have an appetite-reducing effect Long-term effects of 2 energy-restricted diets differing in glycemic load on dietary adherence, body composition, and metabolism in CALERIE: a 1-y randomized controlled trial. |

Lean protein and satiety -

The participants had 15 min to consume the snack and mL i. In addition, computerized, mm visual analog scale questionnaires assessing appetite sensations [ 7 ] were completed every 30 min throughout the afternoon until dinner was voluntarily requested.

Regardless of time of dinner request, the participants were required to remain in the facility until the full 8-h testing day was completed. Water was provided ad libitum throughout the testing day.

For a more detailed description of the methodology, please see refs [ 6 , 8 ] which included similar experimental designs as what was incorporated within the current study.

A repeated measures ANOVA was applied to compare the main effects of snacking on perceived sensations, time to dinner request, and dinner energy content. When main effects were detected, post hoc analyses were performed using Least Significant Difference procedures to identify differences between treatments.

All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences SPSS; version 21; Chicago, IL. Post-snack perceived hunger and fullness are shown in Figure 1. The consumption of each snack led to immediate reductions in hunger and increases in fullness, followed by gradual increases in hunger and decreases in fullness throughout the afternoon until dinner was requested.

No differences in afternoon hunger AUC were detected between the yogurt vs. crackers or between the crackers vs.

No differences in afternoon fullness AUC were observed between the snacks. Additionally, the consumption of the crackers led to greater fullness at 90 min post-snack vs. Appetite and satiety. The post-snack net incremental area under the curve AUC is illustrated in the bar graphs.

No differences in eating initiation were observed between the crackers and chocolate snacks. The ad libitum dinner intake is shown in Figure 2. No differences in dinner intake were observed between the crackers and chocolate. Ad libitum dinner intake following the consumption of each the afternoon snacks in 20 healthy women.

These data suggest that eating less energy dense, high-protein foods like yogurt improves appetite control, satiety, and reduces short-term food intake in women. A macronutrient hierarchy exists in which the satiety effects of foods can be attributed, in part, to their nutritional composition with the consumption of dietary fat having the lowest satiety effect and protein displaying the greatest effect [ 9 — 11 ].

Another closely-linked dietary factor that has strong satiety properties includes the energy density of the foods [ 4 ]. Studies by Rolls et al. Since high-protein foods are typically less energy dense than high-fat foods, it is difficult to tease out the independent effects of macronutrient content and energy density.

However, we have previously shown that, when matched for energy density, the consumption of higher protein meals lead to improved appetite control and satiety compared to normal protein versions [ 14 ].

Several previous snack studies have also examined the combined effects of reduced energy density and increased dietary protein [ 6 , 15 , 16 ]. Specifically, Marmonier et al. However, no difference in dinner intake was observed. In a study by Chapelot et al. However, eating initiation and dinner intake were not different.

Lastly, in our previous study in normal weight women, we examined the effects of kcal afternoon yogurt snacks, varying in energy density and macronutrient content. The less energy dense, high-protein yogurt led to reduced hunger, increased fullness, and delayed subsequent eating compared to the energy dense, high-carbohydrate version [ 6 ].

The inconsistent findings of eating initiation and diner intake between the previous studies and the current study may be attributed to the differences in snack type, macronutrient content, energy content, and energy density.

However, it is important to note that, despite these differences, none of the studies showed a negative effect of consuming a less energy dense, higher protein snack in the afternoon. Further research is necessary to comprehensively identify the effects of less energy dense, protein snacks on energy intake regulation.

We sought to compare the satiety effects following the consumption of commercially-available, commonly consumed afternoon snacks. In using this approach, we were unable to tightly control macronutrient quantity and quality. Specifically, the chocolate snack contained mostly simple carbohydrates 18 g , whereas the crackers included only 2 g of simple carbohydrates.

In addition, the chocolate snack was high in saturated fat 5. simple carbohydrates [ 17 ] and after the consumption of saturated vs.

polyunsaturated fatty acids [ 18 ]. In the current study, no differences in hunger, satiety, or subsequent food intake were detected between the crackers and chocolate, suggesting that the higher saturated fatty acid content of the chocolate may have negated the negative effects of the simply carbohydrates.

Other limitations include the limited assessment of only including perceived sensations of hunger and satiety in normal weight, adult women. Lastly, this was an acute trial over the course of a single day. Longer-term randomized controlled trials are also critical in establishing whether the daily consumption of a less energy dense, high-protein snack improves body weight management.

The less energy dense, high-protein yogurt snack induced satiety and reduced subsequent food intake compared to other commonly consumed snacks, specifically energy dense, high-fat crackers and chocolate. These findings suggest that a less energy dense, high-protein afternoon snack could be an effective dietary strategy to improve appetite control and energy intake regulation in healthy women.

Piernas C, Popkin BM: Snacking increased among U. adults between and J Nutr. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Piernas C, Popkin BM: Increased portion sizes from energy-dense foods affect total energy intake at eating occasions in US children and adolescents: patterns and trends by age group and sociodemographic characteristics, — Am J Clin Nutr.

Duffey KJ, Popkin BM: Energy density, portion size, and eating occasions: contributions to increased energy intake in the United States, — PLoS Med. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Rolls BJ: The relationship between dietary energy density and energy intake.

Physiol Behav. Mo Med. PubMed Google Scholar. Douglas SM, Ortinau LC, Hoertel HA, Leidy HJ: Low, moderate, or high protein yogurt snacks on appetite control and subsequent eating in healthy women.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Flint A, Raben A, Blundell JE, Astrup A: Reproducibility, power and validity of visual analogue scales in assessment of appetite sensations in single test meal studies.

Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. Ortinau LC, Culp JM, Hoertel HA, Douglas SM, Leidy HJ: The effects of increased dietary protein yogurt snack in the afternoon on appetite control and eating initiation in healthy women. Nutr J. Holt SH, Miller JC, Petocz P, Farmakalidis E: A satiety index of common foods.

Eur J Clin Nutr. CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Stubbs RJ, van Wyk MC, Johnstone AM, Harbron CG: Breakfasts high in protein, fat or carbohydrate: effect on within-day appetite and energy balance. Blatt AD, Williams RA, Roe LS, Rolls BJ: Effects of energy content and energy density of pre-portioned entrees on energy intake.

Obesity Silver Spring. Article CAS Google Scholar. Williams RA, Roe LS, Rolls BJ: Assessment of satiety depends on the energy density and portion size of the test meal.

Article Google Scholar. Marmonier C, Chapelot D, Louis-Sylvestre J: Effects of macronutrient content and energy density of snacks consumed in a satiety state on the onset of the next meal.

Chapelot D, Payen F: Comparison of the effects of a liquid yogurt and chocolate bars on satiety: a multidimensional approach. Br J Nutr. Aller EE, Abete I, Astrup A, Martinez JA, van Baak MA: Starches, sugars and obesity.

Kozimor A, Chang H, Cooper JA: Effects of dietary fatty acid composition from a high fat meal on satiety. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Download references. General Mills Bell Institute of Health and Nutrition supplied the funds to complete the study but was not involved in the design, implementation, analysis, or interpretation of data.

In general, dietary protein increases energy expenditure because it has a markedly higher DIT than fat and carbohydrates, and it preserves REE by preventing lean mass loss.

Furthermore, increased DIT increases satiety, which also contributes to weight loss. To the best of our knowledge, Holt et al. In their study, they rated satiety for 38 foods, and protein-rich food received the highest ratings, followed by carbohydrate-rich and fat-rich foods. One of the important mechanisms of HPD-induced satiety involves elevation of the anorexigenic hormones glucagon-like peptide- 1 GLP-1 , cholecystokinin CCK , and peptide tyrosine-tyrosine PYY.

These cells detect nutrients in the gastrointestinal tract and release GLP-1, PYY, and CCK, which increase satiety and decrease food intake.

Ghrelin is an orexigenic hormone that induces food intake by increasing hunger, and its plasma concentration is decreased by protein intake. In conclusion, dietary protein elevates GLP-1, CCK, and PYY levels, which are secreted in the gut and diminish appetite while also decreasing ghrelin levels, which increases appetite.

Such changes in the release of satiety hormones constitute an important mechanism of HPD-induced weight loss. The aminostatic hypothesis, which proposes that elevated levels of plasma AAs increase satiety and, conversely, decrease the plasma AA that induces hunger, was first introduced in Multiple studies reported that HPDs significantly increased plasma AA concentration 38 and satiety 24 , 39 compared with high-fat or high-carbohydrate diets.

However, the aminostatic theory has recently lost support because fasting plasma AA levels are not associated with appetite, and increased plasma AA concentration following protein intake is not consistently associated with appetite. Increased gluconeogenesis due to dietary protein is another mechanism of HPD-induced weight loss.

With HPD, AAs remaining after protein synthesis are involved in an alternative pathway known as gluconeogenesis.

As such, the increased energy usage in gluconeogenesis increases energy expenditure, contributing to weight loss. Compared to a standard diet, high-protein and low-carbohydrate diets increase fasting blood β-hydroxybutyrate concentration.

Elevated β-hydroxybutyrate concentration is known to directly increase satiety. On the other hand, some argue that HPD does not suppress appetite, but only prevents an appetite increase.

Clinical trials with various designs have found that HPD induces weight loss and lowers cardiovascular disease risk factors such as blood triglycerides and blood pressure while preserving FFM. Such weight-loss effects of protein were observed in both energyrestricted and standard-energy diets and in long-term clinical trials with follow-up durations of 6—12 months.

Contrary to some concerns, there is no evidence that HPD is harmful to the bones or kidneys. However, longer clinical trials that span more than one year are required to examine the effects and safety of HPD in more depth. The mechanism underlying HPD-induced weight loss involves an increase in satiety and energy expenditure.

Increased satiety is believed to be a result of elevated levels of anorexigenic hormones, decreased levels of orexigenic hormones, increased DIT, elevated plasma AA levels, increased hepatic gluconeogenesis, and increased ketogenesis from the higher protein intake.

Protein is known to increase energy expenditure by having a markedly higher DIT than carbohydrates and fat, and increasing protein intake preserves REE by preventing FFM decrease Fig. In conclusion, HPD is a safe method for losing weight while preserving FFM; it is thought to also prevent obesity and obesity-related diseases, such as metabolic syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases.

This work was supported by the education, research, and student guidance grant, funded by Jeju National University. Study concept and design: GK; acquisition of data: all authors; analysis and interpretation of data: all authors; drafting of the manuscript: JM; critical revision of the manuscript: GK; obtained funding: GK; administrative, technical, or material support: GK; and study supervision: GK.

HPD, high-protein diet; NS, not significant; BMI, body mass index; FFM, fat-free mass; REE, resting energy expenditure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; FFA, free fatty acids.

Room , Renaissance Tower Bldg. org Powered by INFOrang Co. eISSN pISSN Search All Subject Title Author Keyword Abstract. Previous Article LIST Next Article. kr Received : April 1, ; Reviewed : April 25, ; Accepted : May 19, Keywords : High protein diet, Weight loss, Obesity, Satiation.

Satiety hormones To the best of our knowledge, Holt et al. Aminostatic hypothesis The aminostatic hypothesis, which proposes that elevated levels of plasma AAs increase satiety and, conversely, decrease the plasma AA that induces hunger, was first introduced in Gluconeogensis Increased gluconeogenesis due to dietary protein is another mechanism of HPD-induced weight loss.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Schematic of the proposed high-protein diet-induced weight loss mechanism. Table 1 Summary of studies on HPD Variable Wycherley et al. Lipids, glucose, insulin, and C-reactive protein all improved with weight loss.

HPD group showed sustained favorable effects on serum triglycerides and HDL-C. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight [Internet].

Geneva: World Health Organization; [cited Jul 5]. Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Nieuwenhuizen A, Tomé D, Soenen S, Westerterp KR. Dietary protein, weight loss, and weight maintenance.

Annu Rev Nutr ; Acheson KJ. Diets for body weight control and health: the potential of changing the macronutrient composition. Eur J Clin Nutr ; Wycherley TP, Moran LJ, Clifton PM, Noakes M, Brinkworth GD. Effects of energy-restricted high-protein, low-fat compared with standard-protein, low-fat diets: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Am J Clin Nutr ; Fulgoni VL 3rd. Current protein intake in America: analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Am J Clin Nutr ;SS. Santesso N, Akl EA, Bianchi M, Mente A, Mustafa R, HeelsAnsdell D, et al. Effects of higher- versus lower-protein diets on health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Skov AR, Toubro S, Rønn B, Holm L, Astrup A. Randomized trial on protein vs carbohydrate in ad libitum fat reduced diet for the treatment of obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord ; Weigle DS, Breen PA, Matthys CC, Callahan HS, Meeuws KE, Burden VR, et al. A high-protein diet induces sustained reductions in appetite, ad libitum caloric intake, and body weight despite compensatory changes in diurnal plasma leptin and ghrelin concentrations.

Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Lejeune MP, Nijs I, van Ooijen M, Kovacs EM. High protein intake sustains weight maintenance after body weight loss in humans. Lejeune MP, Kovacs EM, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Additional protein intake limits weight regain after weight loss in humans.

Br J Nutr ; Clifton PM, Keogh JB, Noakes M. Long-term effects of a highprotein weight-loss diet. Layman DK, Evans EM, Erickson D, Seyler J, Weber J, Bagshaw D, et al.

A moderate-protein diet produces sustained weight loss and long-term changes in body composition and blood lipids in obese adults. J Nutr ; Calvez J, Poupin N, Chesneau C, Lassale C, Tomé D.

Protein intake, calcium balance and health consequences. Heaney RP, Layman DK. Amount and type of protein influences bone health. Bonjour JP, Schurch MA, Rizzoli R. Nutritional aspects of hip fractures. Bone ;18 3 Suppl SS. Hannan MT, Tucker KL, Dawson-Hughes B, Cupples LA, Felson DT, Kiel DP.

Effect of dietary protein on bone loss in elderly men and women: the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res ; Friedman AN, Ogden LG, Foster GD, Klein S, Stein R, Miller B, et al. Comparative effects of low-carbohydrate high-protein versus low-fat diets on the kidney.

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol ; Knight EL, Stampfer MJ, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, Curhan GC. The impact of protein intake on renal function decline in women with normal renal function or mild renal insufficiency.

Ann Intern Med ; Millward DJ. Br J Nutr ; Suppl 2:S Martens EA, Tan SY, Dunlop MV, Mattes RD, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Protein leverage effects of beef protein on energy intake in humans. Bray GA, Smith SR, de Jonge L, Xie H, Rood J, Martin CK, et al. Effect of dietary protein content on weight gain, energy expenditure, and body composition during overeating: a randomized controlled trial.

JAMA ; Drummen M, Tischmann L, Gatta-Cherifi B, Adam T, WesterterpPlantenga M. Dietary protein and energy balance in relation to obesity and co-morbidities. Front Endocrinol Lausanne ; Tappy L. Thermic effect of food and sympathetic nervous system activity in humans.

Reprod Nutr Dev ; Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Rolland V, Wilson SA, Westerterp KR. Lippl FJ, Neubauer S, Schipfer S, Lichter N, Tufman A, Otto B, et al. Hypobaric hypoxia causes body weight reduction in obese subjects.

Obesity Silver Spring ; Holt SH, Miller JC, Petocz P, Farmakalidis E. A satiety index of common foods.

Several clinical trials have found ;rotein consuming ans Lean protein and satiety than Sstiety recommended dietary potein not satieth reduces body weight BWsatieyt also enhances body composition by decreasing fat mass while preserving fat-free mass FFM in both low-calorie BMI for Seniors standard-calorie diets. Fairly long-term clinical trials of Herbal antifungal creams months reported Lean protein and satiety a high-protein diet HPD provides weight-loss effects and can prevent weight regain after weight loss. HPD has not been reported to have adverse effects on health in terms of bone density or renal function in healthy adults. Among gut-derived hormones, glucagon-like peptide-1, cholecystokinin, and peptide tyrosine-tyrosine reduce appetite, while ghrelin enhances appetite. HPD increases these anorexigenic hormone levels while decreasing orexigenic hormone levels, resulting in increased satiety signaling and, eventually, reduced food intake. Additionally, elevated diet-induced thermogenesis DITincreased blood amino acid concentration, increased hepatic gluconeogenesis, and increased ketogenesis caused by higher dietary protein contribute to increased satiety.

0 thoughts on “Lean protein and satiety”