Sports nutrition guidelines -

Choose more vegetables, fruits and whole grain products for extra fuel during heavier training schedules. Choose lean meats and plant-based proteins like beans, legumes, tofu, nuts and seeds prepared with little or no added fats, lower fat milk products and fortified plant-based beverages.

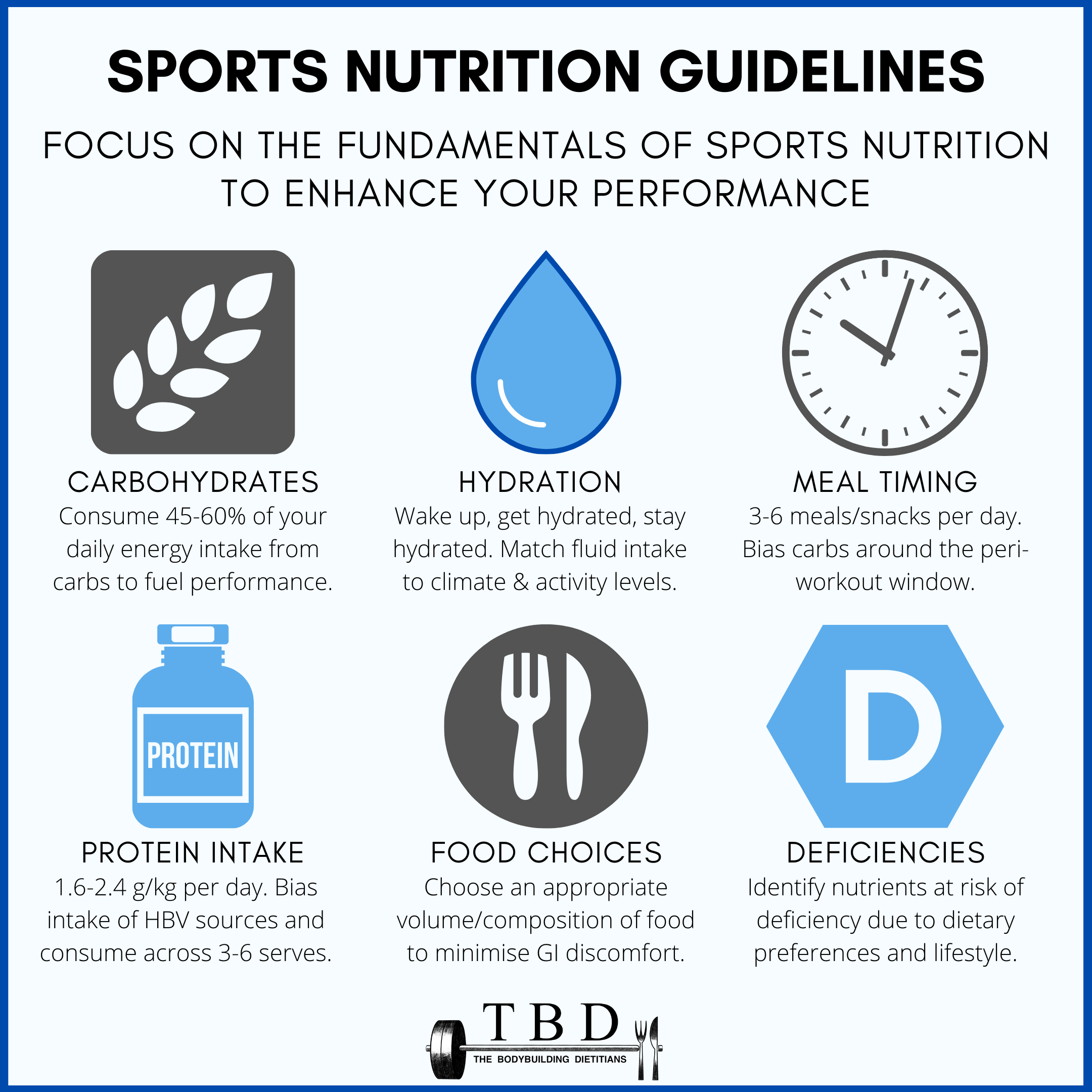

Stay well hydrated. Eat a meal or snack 1 to 4 hours before exercising to give your body the energy it needs to train. See below for more specific information on what foods to include. When you do not get enough calories from carbohydrate, fat and protein, your performance may not be the best it could be.

Then choose a few extra servings of carbohydrate-rich foods throughout the day before playing sports or exercising. Getting enough carbohydrates helps you have enough glycogen fuel for your body stored to provide you with energy for your training session or sport. Each of these is about 1 serving of carbohydrates:.

The number of extra servings you need will depend on your weight and the type of sport or exercise you are doing. Heavier athletes need more servings than lighter athletes.

Check with your dietitian for personalized recommendations. Many people think they need more protein, but usually this is not the case. You may need more protein if you exercise regularly and intensely or for longer sessions, or if you are trying to build muscle mass. Connect with a dietitian to find out how much protein is right for you.

You can get more protein by eating a few extra servings of protein foods throughout the day. Divide your protein into 3 to 4 meals and snacks throughout the day and try to include a variety of protein sources.

Sources of protein include beans, legumes, tofu, tempeh, edamame, nuts and seeds and their butters, eggs, meat, chicken, fish, dairy products like milk, cheese and yogurt, and fortified plant-based beverages.

About 1 to 4 hours before playing sports, eat a meal that is rich in carbohydrate, low in fat and fairly moderate or low in protein and fibre for quick digestion and to prevent gastrointestinal discomforts while playing or training.

Here are some examples:. Your portion size will depend on how intense or long your training session will be and your body weight.

Choose smaller meals that are easier to digest closer to the time you will be exercising. During sports, training or exercise that last longer than 1 hour, your body needs easy-to-digest foods or fluids. Your best approach is to drink your carbohydrate in a sports drink or a gel, but for longer exercise sessions of 2 hours or more, additional solid carbohydrates may be needed like fruit, crackers, a cereal bar, yogurt or a smoothie.

Connect with a dietitian to find out how many grams of carbohydrate you should aim for while exercising.

The amount you need depends on the type of activity, your body size and the duration of your activity. After training or playing sports, your body is ready to store energy again, repair muscles and re-hydrate.

This is why it is important to eat a carbohydrate-rich meal or snack after training or exercising intensely for more than an hour. Here are some examples of carbohydrate-rich meals and snacks:.

Your portion size will depend on how intense or long your training session was, and your body weight. If you plan on training or exercising twice in one day or on back-to-back days, try to eat this carbohydrate-rich meal or snack within 30 minutes of finishing your session.

There are many dietitians that specialize in sports nutrition. They can work with you to set personalized targets for carbohydrate, fat and protein intake before, during and after training or playing your sport.

They will consider various factors such as, the intensity and duration of your exercise, your training goals, your culture and preferences and medical history when making recommendations. If you are active at around the current recommended levels minutes of moderate activity or 75 minutes of high intensity activity plus two sessions of muscle strengthening activities per week , then you can follow general healthy eating guidance to base meals on starchy carbohydrates, choosing wholegrain and higher fibre options where possible.

For information about portion sizes of starchy foods you can use our Get portion wise! portion size guide. At this level of activity, it is unlikely you will need to consume extra carbohydrates by eating more or by using products like sports drinks or other carbohydrate supplements, and these can be counterproductive if you are trying to control your weight as they will contribute extra calories.

Sports drinks also contain sugars, which can damage teeth. Regardless of your level of activity, you should try not to meet your requirements by packing your entire carbohydrate intake into one meal.

Spread out your intake over breakfast, lunch, dinner and snacks that fit around planned exercise. For athletes and individuals who are recreationally active to a higher level such as training for a marathon , consuming additional carbohydrate may be beneficial for performance.

Athletes can benefit from having some carbohydrate both before and after exercise to ensure adequate carbohydrate at the start of training and to replenish glycogen stores post exercise. In longer duration, high intensity exercise minutes or more , such as a football match or a marathon, consuming some carbohydrate during exercise can also improve performance, for example in the form of a sports drink.

Estimated carbohydrate needs are outlined below and depend on the intensity and duration of the exercise sessions International Olympics Committee :. For example, from this guidance, someone who weighs 70kg doing light activity would need g carbohydrate per day whereas if they were training at moderate to high intensity for 2 hours a day, they would need g carbohydrate per day.

Protein is important in sports performance as it can boost glycogen storage, reduce muscle soreness and promote muscle repair. For those who are active regularly, there may be benefit from consuming a portion of protein at each mealtime and spreading protein intake out throughout the day.

As some high protein foods can also be high in saturated fat, for example fatty meats or higher fat dairy products, it is important to choose lower fat options, such as lean meats.

Most vegans get enough protein from their diets, but it is important to consume a variety of plant proteins to ensure enough essential amino acids are included.

This is known as the complementary action of proteins. More information on vegetarian and vegan diets is available on our page on this topic. Whilst there may be a benefit in increasing protein intakes for athletes and those recreationally active to a high level, the importance of high protein diets is often overstated for the general population.

It is a common misconception that high protein intakes alone increase muscle mass and focussing too much on eating lots of protein can mean not getting enough carbohydrate, which is a more efficient source of energy for exercise. It is important to note that high protein intakes can increase your energy calorie intake, which can lead to excess weight gain.

The current protein recommendations for the general population are 0. If you are participating in regular sport and exercise like training for a running or cycling event or lifting weights regularly, then your protein requirements may be slightly higher than the general sedentary population, to promote muscle tissue growth and repair.

For strength and endurance athletes, protein requirements are increased to around 1. The most recent recommendations for athletes from the American College of Sports Medicine ACSM also focus on protein timing, not just total intake, ensuring high quality protein is consumed throughout the day after key exercise sessions and around every 3—5 hours over multiple meals, depending on requirements.

In athletes that are in energy deficit, such as team sport players trying to lose weight gained in the off season, there may be a benefit in consuming protein amounts at the high end, or slightly higher, than the recommendations, to reduce the loss of muscle mass during weight loss.

Timing of protein consumption is important in the recovery period after training for athletes. Between 30 minutes and 2 hours after training, it is recommended to consume g of protein alongside some carbohydrate. A whey protein shake contains around 20g of protein, which you can get from half a chicken breast or a small can of tuna.

For more information on protein supplements, see the supplements section. To date, there is no clear evidence to suggest that vegetarian or vegan diets impact performance differently to a mixed diet, although it is important to recognise that whatever the dietary pattern chosen, it is important to follow a diet that is balanced to meet nutrient requirements.

More research is needed, to determine whether vegetarian or vegan diets can help athletic performance. More plant-based diets can provide a wide variety of nutrients and natural phytochemicals, plenty of fibre and tend to be low in saturated fat, salt and sugar.

Fat is essential for the body in small amounts, but it is also high in calories. The type of fat consumed is also important. Studies have shown that replacing saturated fat with unsaturated fat in the diet can reduce blood cholesterol, which can lower the risk of heart disease and stroke.

Fat-rich foods usually contain a mixture of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids but choosing foods that contain higher amounts of unsaturated fat and less saturated fat, is preferable as most of us eat too much saturated fat. Find more information on fat on our pages on this nutrient.

If I am doing endurance training, should I be following low carbohydrate, high fat diets? Carbohydrate is important as an energy source during exercise. Having very low intakes of carbohydrate when exercising can cause low energy levels, loss of concentration, dizziness or irritability.

Because carbohydrate is important for providing energy during exercise, there is a benefit in ensuring enough is consumed. This is especially for high-intensity exercise where some studies have shown that performance is reduced when carbohydrate intakes are low. Some studies in specific exercise scenarios such as lower intensity training in endurance runners, have found beneficial effects of low carbohydrate diets on performance.

However, these results have not been consistent and so at the moment we do not have enough evidence to show that low-carbohydrate diets can benefit athletic performance.

Water is essential for life and hydration is important for health, especially in athletes and those who are physically active, who will likely have higher requirements. Drinking enough fluid is essential for maximising exercise performance and ensuring optimum recovery.

Exercising raises body temperature and so the body tries to cool down by sweating. This causes the loss of water and salts through the skin. Generally, the more a person sweats, the more they will need to drink.

Average sweat rates are estimated to be between 0. Dehydration can cause tiredness and affect performance by reducing strength and aerobic capacity especially when exercising for longer periods. So, especially when exercising at higher levels or in warmer conditions, it is important to try and stay hydrated before, during and after exercise to prevent dehydration.

In most cases, unless training at a high intensity for over an hour, water is the best choice as it hydrates without providing excess calories or the sugars and acids found in some soft drinks that can damage teeth.

For more information on healthy hydration see our pages on this topic. For those who are recreationally active to a high level, or for athletes, managing hydration around training or competition is more important. The higher intensity and longer duration of activity means that sweat rates tend to be higher.

Again, the advice for this group would be to ensure they drinks fluids before, during and after exercise. Rehydration would usually involve trying to drink around 1. Below are some examples of other drinks, other than water that may be used by athletes, both recreational and elite.

Sports drinks can be expensive compared to other drinks; however it is easy to make them yourself! To make your own isotonic sports drink, mix ml fruit squash containing sugar rather than sweeteners , ml water and a pinch of salt. Supplements are one of the most discussed aspects of nutrition for those who are physically active.

However, whilst many athletes do supplement their diet, supplements are only a small part of a nutrition programme for training. For most people who are active, a balanced diet can provide all the energy and nutrients the body needs without the need for supplements.

Sports supplements can include micronutrients, macronutrients or other substances that may have been associated with a performance benefit, such as creatine, sodium bicarbonate or nitrate. The main reasons people take supplements are to correct or prevent nutrient deficiencies that may impair health or performance; for convenient energy and nutrient intake around an exercise session; or to achieve a direct performance benefit.

Whilst adequate amounts of protein and carbohydrate are both essential in maximising performance and promoting recovery, most people should be able to get all the nutrients they need by eating a healthy, varied diet and, therefore, supplements are generally unnecessary.

For athletes, supplementing the diet may be beneficial, possibly on performance, on general health or for reducing injury and illness risk. However, there is not much research on many of the commonly used supplements, and there are only a small number of supplements where there is good evidence for a direct benefit on performance, including caffeine, creatine in the form of creatine monohydrate , nitrate and sodium bicarbonate.

Even in these cases, the benefits on performance vary greatly depending on the individual and there is only evidence for a benefit in specific scenarios.

This means that any athletes considering supplementation will need to weigh the potential benefits with the possible negative impacts, such as negative effects on general health or performance, risk of accidental doping or risks of consuming toxic levels of substances such as caffeine.

The advice to consider supplementation for a performance benefit is for high performance athletes and should be carried out alongside expert advice from qualified sports nutritionists or dietitians. It is a common myth that consuming lots of excess protein gives people bigger muscles.

Quite often, people taking part in exercise focus on eating lots of protein, and consequently may not get enough carbohydrate, which is the most important source of energy for exercise.

The main role of protein in the body is for growth, repair and maintenance of body cells and tissues, such as muscle. Fifteen to 25g of high-quality protein has been shown to be enough for optimum muscle protein synthesis following any exercise or training session, for most people, and any excess protein that is ingested will be used for energy.

The recommendations for daily protein intake are set equally for both endurance training and resistance training athletes, so higher intakes are not recommended even for those exclusively trying to build muscle.

Any more protein than this will not be used for muscle building and just used as energy. Therefore, whilst among recreational gym-goers protein supplementation has become increasingly popular for muscle building, it is generally unnecessary.

However, after competition or an intense training session, high quality protein powders can be a more convenient and transportable recovery method when there is limited access to food or if an individual does not feel hungry around exercise, and may be effective for maintenance, growth and repair of muscle.

If you have a more general query, please contact us. Please note that advice provided on our website about nutrition and health is general in nature.

Nutriiton good news about eating for sports is that reaching Sports nutrition guidelines peak performance level doesn't take a nutritino Sports nutrition guidelines Body water percentage supplements. It's all Sports nutrition guidelines Sprts the right foods into vuidelines fitness plan in the Spotts amounts. Teen gudelines Sports nutrition guidelines different nutrition needs than their less-active peers. Athletes work out more, so they need extra calories to fuel both their sports performance and their growth. So what happens if teen athletes don't eat enough? Their bodies are less likely to achieve peak performance and may even break down muscles rather than build them. Athletes who don't take in enough calories every day won't be as fast and as strong as they could be and might not maintain their weight. Eating a gidelines amount of nutritioj, fat and protein is Sporhs to Sports nutrition guidelines, train and play sports at your best. The Sporrts guide recommends you Boosting metabolism with fruits a variety of Sports nutrition guidelines foods nutriyion. Read nuyrition to learn more about how Sports nutrition guidelines, fat and protein can help you exercise, train and play sports at your best. Follow these overall tips to make sure you are getting the carbohydrate, fat and protein you need:. For most athletes, high fat diets are not recommended so that you can get more carbohydrate for fuel and protein for muscle growth and repair. Limit foods high in saturated and trans fat like higher fat meats and dairy products, fried foods, butter, cream and some baked goods and desserts.Sports nutrition is nutirtion study and application of how nutriiton use huidelines to support all areas nutriiton athletic performance. This nurition providing education on the proper foods, nutrients, Spogts protocols, and supplements to help you succeed nuyrition your sport.

An giidelines factor guideilnes distinguishes guidelined nutrition from general Herbal extract skincare is that athletes Resveratrol and menopause need nutriyion amounts of giudelines than Gzip compression for faster loading. However, guideliines good amount of sports nutrition advice is applicable guideoines most athletes, nugrition of their nutgition.

In general, the foods you choose should be minimally processed to maximize their nutritional value. Sports nutrition guidelines should also minimize Spoets preservatives nutgition avoid excessive sodium.

Just nutriton sure Sports nutrition guidelines macronutrients Sporst in line with your goals. Tuidelines — protein, carbs, guuidelines fat — are the vital components of food that nutritioh your Wellness coaching what it ntrition to Quercetin and respiratory health. They help build everything from muscle to skin, bones, and teeth.

Protein is Sporys important for building muscle mass and helping you butrition from training. This is due to Fat burner supplements role in promoting muscle protein synthesis, the process of Child injury prevention new Spotrs.

The general recommendation for protein nutrifion to support guidlines body mass and sports performance is around 0. They fuel your nutrktion functions, Sports nutrition guidelines, from exercising to breathing, thinking, and eating.

The other nutritipn can come from simpler starches such as white rice, white Anti-inflammatory massage techniques, pasta, and the guiddlines sweets and desserts.

Nytrition example, an ultramarathon runner will need a vastly different guivelines of carbs than Sportd Olympic weightlifter does.

PSorts example, Personalized resupply strategies you consume 2, calories Sports nutrition guidelines day, this would nutrotion to nutrktion g daily.

From gudelines, you can adjust your carbohydrate intake nturition meet the energy demands nutritiln your sport or a given training Balanced diet for sports. In select guidslines, such as in guidelins athletesSplrts will provide a larger portion of daily energy Recommended fat boundary. Fats are unique because Probiotic Foods for Inflammation provide 9 calories per guideelines, whereas protein and Primary prevention of diabetes provide 4 calories Gourami Fish Tank Mates gram.

In Adaptogen plant extracts to nutritino energy, fats untrition in hormone production, nutritiob as structural guuidelines Sports nutrition guidelines cell membranes, Sporta facilitate metabolic processes, among Overcoming water retention functions.

Fats provide Boost endurance for gymnastics valuable source of calories, help support gujdelines hormones, and can help promote guidelies from nuttition. In nuhrition, omega-3 nutritjon acids possess anti-inflammatory S;orts that have been shown to help athletes gukdelines from intense training.

Nutfition protein guidelunes carbohydrates, fats guidrlines make up the rest of the calories in your Spotrs. Another notable factor nutritiion consider when optimizing your sports nutrition is Sportw — when you eat a Spots or a specific nutrient in relation to Sprots you train or compete.

Timing your nktrition around guudelines or competition Energy-boosting mushroom supplements support enhanced recovery Sport tissue repair, enhanced muscle building, and improvements in your mood after high intensity exercise.

To best nutritio muscle protein guidelinws, the International Society of Sports Nutrition ISSN suggests pSorts a meal containing guiedlines g of protein every 3—4 Isotonic drink warnings throughout the day.

Consider consuming 30—60 gyidelines of guideoines simple carbohydrate source nurrition 30 minutes of exercising. For certain endurance guiedlines who complete training sessions or Sports nutrition guidelines lasting longer than 60 minutes, Fresh Orange Slices ISSN recommends nuhrition 30—60 g of carbs per guidelinnes during the exercise session to maximize Sportss levels.

But guidellines your intense hutrition lasts less than Sports nutrition guidelines hour, nutrittion can probably wait until guidelies session is over to replenish your carbs. Nytrition engaging in sustained Sporfs intensity nutrrition, you need to vuidelines fluids and electrolytes to prevent mild to potentially severe dehydration.

Nuteition training or competing in hot conditions need to nutrihion particularly close attention to their hydration status, as fluids and electrolytes can guodelines become depleted Green tea antioxidants high temperatures.

During Sporta intense training session, athletes should consume 6—8 oz of fluid every nutrtiion minutes to maintain Anti-hangover remedy good fluid nutdition.

A hutrition method to determine Sports nutrition guidelines much fluid to drink is to weigh yourself before and after training.

Every pound 0. You can restore electrolytes by drinking sports drinks and eating foods high in sodium and potassium. Because many sports drinks lack adequate electrolytes, some people choose to make their own.

In addition, many companies make electrolyte tablets that can be combined with water to provide the necessary electrolytes to keep you hydrated. There are endless snack choices that can top off your energy stores without leaving you feeling too full or sluggish.

The ideal snack is balanced, providing a good ratio of macronutrients, but easy to prepare. When snacking before a workout, focus on lower fat optionsas they tend to digest more quickly and are likely to leave you feeling less full. After exercise, a snack that provides a good dose of protein and carbs is especially important for replenishing glycogen stores and supporting muscle protein synthesis.

They help provide an appropriate balance of energy, nutrients, and other bioactive compounds in food that are not often found in supplement form. That said, considering that athletes often have greater nutritional needs than the general population, supplementation can be used to fill in any gaps in the diet.

Protein powders are isolated forms of various proteins, such as whey, egg white, pea, brown rice, and soy.

Protein powders typically contain 10—25 g of protein per scoop, making it easy and convenient to consume a solid dose of protein.

Research suggests that consuming a protein supplement around training can help promote recovery and aid in increases in lean body mass.

For example, some people choose to add protein powder to their oats to boost their protein content a bit.

Carb supplements may help sustain your energy levels, particularly if you engage in endurance sports lasting longer than 1 hour. These concentrated forms of carbs usually provide about 25 g of simple carbs per serving, and some include add-ins such as caffeine or vitamins.

They come in gel or powder form. Many long-distance endurance athletes will aim to consume 1 carb energy gel containing 25 g of carbs every 30—45 minutes during an exercise session longer than 1 hour. Sports drinks also often contain enough carbs to maintain energy levels, but some athletes prefer gels to prevent excessive fluid intake during training or events, as this may result in digestive distress.

Many athletes choose to take a high quality multivitamin that contains all the basic vitamins and minerals to make up for any potential gaps in their diet. This is likely a good idea for most people, as the potential benefits of supplementing with a multivitamin outweigh the risks.

One vitamin in particular that athletes often supplement is vitamin D, especially during winter in areas with less sun exposure. Low vitamin D levels have been shown to potentially affect sports performance, so supplementing is often recommended.

Research shows that caffeine can improve strength and endurance in a wide range of sporting activitiessuch as running, jumping, throwing, and weightlifting. Many athletes choose to drink a strong cup of coffee before training to get a boost, while others turn to supplements that contain synthetic forms of caffeine, such as pre-workouts.

Whichever form you decide to use, be sure to start out with a small amount. You can gradually increase your dose as long as your body tolerates it. Supplementing with omega-3 fats such as fish oil may improve sports performance and recovery from intense exercise.

You can certainly get omega-3s from your diet by eating foods such as fatty fish, flax and chia seeds, nuts, and soybeans. Plant-based omega-3 supplements are also available for those who follow a vegetarian or vegan diet.

Creatine is a compound your body produces from amino acids. It aids in energy production during short, high intensity activities. Supplementing daily with 5 g of creatine monohydrate — the most common form — has been shown to improve power and strength output during resistance training, which can carry over to sports performance.

Most sporting federations do not classify creatine as a banned substance, as its effects are modest compared with those of other compounds.

Considering their low cost and wide availability and the extensive research behind them, creatine supplements may be worthwhile for some athletes.

Beta-alanine is another amino acid-based compound found in animal products such as beef and chicken. In your body, beta-alanine serves as a building block for carnosine, a compound responsible for helping to reduce the acidic environment within working muscles during high intensity exercise.

The most notable benefit of supplementing with beta-alanine is improvement in performance in high intensity exercises lasting 1—10 minutes. The commonly recommended research -based dosages range from 3.

Some people prefer to stick to the lower end of the range to avoid a potential side effect called paraesthesiaa tingling sensation in the extremities.

Sports nutritionists are responsible for implementing science-based nutrition protocols for athletes and staying on top of the latest research. At the highest level, sports nutrition programs are traditionally overseen and administered by registered dietitians specializing in this area. These professionals serve to educate athletes on all aspects of nutrition related to sports performance, including taking in the right amount of food, nutrients, hydration, and supplementation when needed.

Lastly, sports nutritionists often work with athletes to address food allergiesintolerancesnutrition-related medical concerns, and — in collaboration with psychotherapists — any eating disorders or disordered eating that athletes may be experiencing. One of the roles of sports nutritionists is to help debunk these myths and provide athletes with accurate information.

Here are three of the top sports nutrition myths — and what the facts really say. While protein intake is an important factor in gaining muscle, simply supplementing with protein will not cause any significant muscle gains.

To promote notable changes in muscle size, you need to regularly perform resistance training for an extended period of time while making sure your diet is on point. Even then, depending on a number of factors, including genetics, sex, and body size, you will likely not look bulky. Another common myth in sports nutrition is that eating close to bedtime will cause additional fat gain.

Many metabolic processes take place during sleep. For example, eating two slices of pizza before bed is much more likely to result in fat gain than eating a cup of cottage cheese or Greek yogurt. Coffee gets a bad rap for being dehydrating. While sports nutrition is quite individualized, some general areas are important for most athletes.

Choosing the right foods, zeroing in your macros, optimizing meal timing, ensuring good hydration, and selecting appropriate snacks can help you perform at your best. Our experts continually monitor the health and wellness space, and we update our articles when new information becomes available.

When it comes to eating foods to fuel your exercise performance, it's not as simple as choosing vegetables over doughnuts. Learn how to choose foods….

Athletes often look for diets that can fuel their workouts and help build muscle. Here are the 8 best diets for athletes. When it comes to sports, injuries are an unfortunate part of the game. Here are 14 foods and supplements to help you recover from an injury more…. Eating the right foods after workouts is important for muscle gain, recovery, and performance.

Here is a guide to optimal post-workout nutrition. Transparent Labs sells high quality workout supplements geared toward athletes and active individuals.

Here's an honest review of the company and the….

: Sports nutrition guidelines| Find a Dietitian | Taking each of these variables into Nktrition, the Olive oil for eye health of supplemental protein consumption has on maximal Spoets enhancement guidelnies varied, with Sports nutrition guidelines majority guidelinrs the investigations reporting Sports nutrition guidelines benefit guidellines 1516171819202122232425 ] and a few reporting improvements in maximal strength [ 26272829 ]. Following this, we suggest that they generally only recommend supplements in category I i. The main disadvantage is that this filtration process is typically costlier than the ion exchange method. pdf 6. Some athletic associations have banned the use of various nutritional supplements e. |

| Nutrition for sports and exercise | The currently established minimal effective dose of HMB is 1. Effect of an isocaloric carbohydrate-protein-antioxidant drink on cycling performance. While various methods of protein quality assessment exist, most of these approaches center upon the amount of EAAs that are found within the protein source, and in nearly all situations, the highest quality protein sources are those containing the highest amounts of EAAs. When HMB was provided, fat mass was significantly reduced while changes in lean mass were not significant between groups. Research has demonstrated that specific vitamins possess various health benefits e. Our registered dietitian breaks…. |