Satiety and nutritional value -

Multivariate analysis allows us to identify statistically significant variables in a complex system like our food matrix. While many factors correlate with eating less, multivariate analysis enables us to identify statistically significant parameters to focus on.

The table below shows the results of the multivariate analysis when we only consider macronutrients and fibre. So, at the highest level, a diet prioritising protein and minimally processed whole foods that contain fibre and less energy from non-fibre carbohydrates and fat will provide greater satiety.

Specific appetite also known as specific hunger refers to the desire or craving for a particular type of food or nutrient that the body needs to maintain proper functioning or to correct a deficiency. For example, if the body is low on iron, it may crave red meat or other iron-rich foods.

Similarly, if your blood glucose is low, you may crave sweets or sugary foods that quickly boost your blood glucose. At the highest level, we tend to have an appetite to balance protein vs. energy by pairing complementary foods, like steak and egg, fish and chips, or bangers and mash.

The good news is that foods containing protein also tend to contain many other micronutrients. Our analysis of the Optimiser data shows that natural foods that contain more protein also tend to have riboflavin B2 , niacin B3 , pantothenic acid B5 , cobalamin B12 , potassium, selenium, cholesterol, and iron.

According to professors Raubenheimer and Simpson , animals—including humans—possess specific appetites for protein, carbohydrates, fat, and at least two micronutrients—salt and calcium. Their paper, An integrative approach to dietary balance across the life course , noted that specific appetites for other nutrients likely exist.

Various studies, like Solmns, , Ganzle et al. For example, glycine tastes sweet , while proline, isoleucine, and valine taste bitter.

Glutamine provides an umami flavour , which is often added to processed foods i. The figure below from our satiety analysis shows that consuming more of each amino acid per calorie aligns with eating less.

Multivariate analysis of the amino acid data shows methionine has the most statistically significant correlation with eating less. Salt—or sodium—is a mineral we have a robust conscious taste for. Thus, we crave it when we need more of it and stop adding salt once we get enough salt and our food tastes too salty.

Ultra-processed food manufacturers exploit this phenomenon by adding salt to junk food. Hence we are often advised to minimise salt. Calcium is another mineral that many believe we have an innate specific appetite for Tordoff, We need adequate calcium to build our bones and move energy around our cells.

We also need calcium for fluid balance, muscle contraction, and circulation. But, as you will see, we seem to eat a lot less when we get plenty of potassium. While we have an innate taste and craving for nutrients like protein and sodium, we can learn to associate the nutrients that alleviate deficiencies with the taste, texture and smell of foods that contain particular nutrients that we need more of i.

Researchers like Dr Fred Provenza have shown that animals forage for just the right amount of complimentary nutrients and other substances from their food and associate taste with nutrients. Provenza has also demonstrated that animals learn to associate a nutrient with particular flavours and seek out the flavours associated with the nutrients they are currently deficient in.

However, this learned appetite is diminished in domesticated animals which subsist on fortified feed. This may also be the case in modern humans exposed to processed foods packed with flavouring, colours, and fortification that are designed to mimic nutritious food.

In the s, paediatrician Clara Davis studied 15 newly weaned infants in an orphanage.. She gave them a wide range of weird and wonderful foods and noticed that each child selected various foods daily to meet their nutritional needs. It seems we have an innate ability to seek out what we need.

In addition to an appetite for the nutrients we need more of, we can also have an aversion to foods that contain too much of a particular nutrient when we already have plenty e.

However, once they had exceeded the daily recommended intake of a particular nutrient, participants preferred other foods that contained complementary micronutrients. As we dug into the data, we noticed that getting more of each essential nutrient per calorie also aligns with eating less.

So, given the intriguing research, I wondered if there may be a broader nutrient leverage effect rather than merely protein leverage. With this data, we could perhaps identify the other nutrients we have an appetite for, either innate or learned, and use that information to satisfy our cravings for less energy.

The chart below shows the satiety response to all the minerals. While getting more of each of the minerals per calorie aligns with a lower calorie intake, larger macrominerals like potassium, sodium, and calcium tend to have a larger impact on calorie intake.

When we look at vitamins, we see a similar trend, although to a lesser degree. This smaller effect may be because vitamins are common in supplements and food fortification.

Meanwhile, larger macrominerals like potassium and calcium are too large to be cost-effectively used in supplements and fortification. While each essential nutrient correlates with greater satiety, we are unlikely to simultaneously have dominant appetites for all the micronutrients. To understand if micronutrients have an impact on how much we eat, we ran a multivariate analysis on the Optimiser data.

The table below shows the results of the multivariate analysis when we consider each macronutrient, essential mineral, vitamin, and cholesterol. The most surprising finding from this multivariate analysis is that consuming foods with more cholesterol—like eggs and liver—has a statistically significant relationship with eating less.

When all other nutrients are considered, moving from 0. The chart below shows that people eating foods containing more cholesterol per calorie tend to eat less. Interestingly, dietary cholesterol in our food system has declined since the s, while obesity has continued to rise.

Until recently, dietary cholesterol was considered a nutrient we should avoid. However, this recommendation was removed from the US Dietary Guidelines in after extensive research, as it was found that dietary cholesterol did not play a role in cardiovascular disease.

Cholesterol is not considered an essential nutrient because our livers make most of what our bodies require. Whether or not we have a specific appetite for cholesterol, this analysis suggests that avoiding otherwise nutritious foods like meat, eggs, and liver that naturally contain cholesterol may lead us to consume lower-satiety foods.

As the satiety analysis chart below shows, Optimisers consuming more calcium per calorie tend to eat fewer calories. However, our cravings for calcium seem to taper off once we get enough or when our cravings are satisfied.

The calcium content of our food system has also declined since the s. Sodium is another nutrient that has decreased in our food system. The multivariate analysis indicates that we may have the strongest innate cravings for potassium.

Or at least, we tend to eat less when we consume foods that contain more potassium per calorie. This observation aligns with the study, Increment in Dietary Potassium Predicts Weight Loss in the Treatment of the Metabolic Syndrome , which showed that more dietary potassium aligned with greater weight loss.

Unfortunately, cholesterol is not always measured in food. So, I re-ran the multivariate analysis without cholesterol. In this scenario, we see that protein still dominates while potassium, sodium, and calcium still elicit a significant satiety response.

This iteration also shows that pantothenic acid B5 and folate B9 make a small contribution to the satiety equation. The multivariate analysis of the Optimiser data provides regression coefficients for each nutrient. This allows us to estimate how much we would eat of a particular food or meal based on its macronutrient and micronutrient profile.

From this, we have developed an updated food satiety index to apply to any food or meal! For simplicity, foods are ranked from 0 least satiating to most satiating. To demonstrate how the Satiety Index Score works in practice, the chart below shows recipes from our NutriBooster recipe books that our Optimisers can use in our Macros Masterclasses and Micros Masterclasses.

Again, the recipes shown in green have a higher Satiety Index Score, while those in red have the lowest. You can dive into the detail of this chart to learn more about the recipes by opening the interactive Tableau version on your computer.

The most satiating and nutritious recipes tend to be lean seafood with some non-starchy veggies followed by meat and eggs. In the lower corner, we have more energy-dense, lower-protein recipes that might be appropriate if you need more energy to support growth or activity.

To be clear, any study that tests hunger three hours after eating only measures short-term satiation, not long-term satiety. Various studies have shown that foods with a lower energy density tend to be harder to overeat in the short term i.

However, taken to the extreme, very low-energy-density foods simply contain more added water to reduce their energy density. A big glass of water will only keep you feeling full for so long!

Energy density is also hard to measure in the real world. Overall, foods and meals with a higher Satiety Index Score tend to be lower in fat and higher in fibre, so they will have a lower energy density than ultra-processed foods.

We evaluated energy density in the multivariate analysis but found that it is not statistically significant in the satiety equation once the other factors mentioned above are considered. Ultra-processed foods UPFs have become more prevalent in our food system due to their taste, cost, convenience, and profit margin.

Ultra-processed foods tend to contain a blend of ingredients and often need artificial flavours, colours, and fortification to make them palatable. The NOVA classification system is typically used to define ultra-processed foods.

While we should ideally minimise these ultra-processed foods, prioritising foods with more essential nutrients that align with greater satiety will automatically eliminate UPFs without adding other subjective factors.

In Supra-Additive Effects of Combining Fat and Carbohydrate on Food Reward , Professor Dana Small and colleagues showed that consuming fat and carbs elicits a dopamine response to reinforce energy consumption and ensure survival.

When we looked at the properties of food that align with eating more, we found that sugar, saturated fat, starch, and monounsaturated fat correlate with eating more.

We all need some energy to survive. However, when we isolate and refine these energy sources and combine them in ultra-processed foods, we create a supra-additive dopamine response that makes us want to eat and buy!

more of them. At the bottom of the results table, we see that starch and monounsaturated fat align with eating more when considering the other factors. One potential benefit of this analysis scenario is that it puts a little less emphasis on protein and highlights other beneficial nutrients like folate, selenium, and vitamin B2.

It also shows us that we should avoid foods that contain starch and monounsaturated fat together, which are rarely found alongside one another in whole foods. However, this system is less resilient because these other parameters like sugar, saturated fat, starch, and monounsaturated fat are not always measured in food.

Despite the added complexity, it makes a negligible difference to the Satiety Index Score. As you eat more of a particular kind of food, you begin to feel less pleasure and may feel full or even repelled by it while still being able to eat other foods.

Based on what we understand about our cravings for nutrients, sensory-specific satiety may be occurring because we get our fill of the nutrients we require from one food. Thus, we are more interested in other foods that contain the nutrients we still require more of.

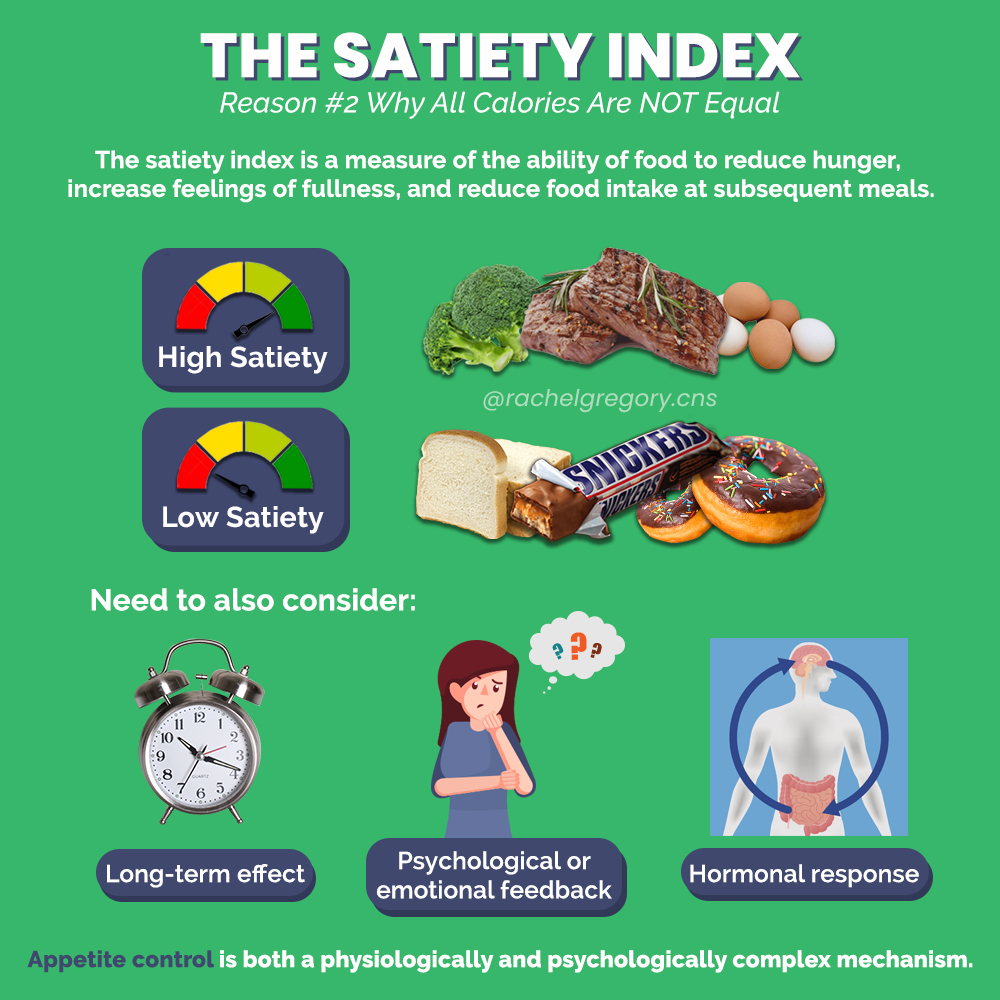

High-satiety meals tend to be lower in energy from both carbs and fat. This helps to stabilise blood glucose levels and draw down excess glycogen from your liver while also allowing your body to use your stored body fat. A range of hormones like GLP-1, CCK, PYY, ghrelin, insulin and leptin play a fascinating and complex role in signalling hunger and satiety.

Recently, there has been a lot of interest in expensive drugs that artificially mimic GLP-1 in our bodies to manipulate satiety without the nutrients that naturally stimulate it. But we can make plenty of GLP-1 in our body for free! if we prioritise the nutrients we require in the food we eat.

For more, see Weight Loss Drugs: Does Satiety Now Come in a Needle? Due to the decline of nutrients like protein, potassium, and calcium in our food system thanks to the advent of industrial agriculture fuelled by synthetic fertilisers, the priority nutrients are likely similar for most people i.

We anticipate that the precise satiety equation would be unique for each individual based on their current diet. For example, someone following a strict vegan diet would have different priority nutrients that could increase their satiety compared to someone following a carnivorous diet.

In our Micros Masterclass , we guide Optimisers to track their diet and use it to identify their unique micronutrient fingerprint. The example shows that nutrients towards the top of the chart, like calcium, vitamin E, thiamine, iron, and vitamin D, need to be prioritised.

The vertical black line represents the Optimal Nutrient Intake , a stretch target for each nutrient. In our Micros Masterclass , Optimisers use Nutrient Optimiser to identify foods and meals that provide more of their priority nutrients to balance their diet at the micronutrient level.

To identify your priority nutrients and the foods and meals that will fill the gaps, you can take our Free 7-Day Nutrient Clarity Challenge. While optimising your diet at the micronutrient level is the pinnacle of Nutritional Optimisation , tracking and fine-tuning your diet takes a little work.

Most people find it easier to start their journey of Nutritional Optimisation by using our optimised food lists and NutriBooster recipe books tailored to their preferences and goals.

This is anecdotal but a large, calorie bowl of oatmeal leaves me feeling stuffed for hours. So does a healthy serving of microwaved potatoes with some butter or sour cream. Supported by research.

Anecdotally, I enjoy legumes greatly, and feel much, much better after eating legumes as opposed to any grain, even the most fibre-rich, whole grain products. And, cooking, with a pressure cooker, most phytic acid is removed, digestive issues reduced, cooking time reduced.

In my analysis legumes make the shortlist if you want to eliminate animal based foods. However animal based foods tend to be more nutrient dense not to mention bioavailable.

My worry would be the effect of animal protein-centered diet of long term health and mortality. Centenarian populations have low levels of animal protein in their diet.

If I swap most of the legumes and grains for more animal protein I wory I will die earlier. In contrast, where the preload was high in protein 57 , a significant suppression of appetite ratings was observed. Moreover, it is important to highlight that a recent development in the food science community is the ability to create products such as hydrogel-based that do not contain any calories.

As these gels are novel products, they are also free from any prior learning or expected postprandial satisfaction that could influence participants. These hydrogels have been proven to have an impact on satiety 26 and satiation 29 suggesting there is an effect of food texture alone, independent of calories and macronutrients composition.

An important factor that may also explain variation in outcomes, may be the timing between preload and test meal. It has been argued that the longer the time interval between preload and test meal the lower the effect of preload manipulation Accordingly, the range of intervals between preload and test meal differed substantially across the studies included in this systematic review: from 10 to min.

Studies with a shorter time interval 10—15 min between preload and ad libitum food intake showed an effect of food texture on subsequent food intake 26 , 27 , In contrast, those studies with a longer time interval, such as Camps et al. As such, it can be deduced that the effects of texture might be more prominent in studies tracking changes in appetite and food intake over a shorter period following the intervention.

In addition, the energy density of the preload is a key factor that should not be discounted when designing satiety trials on food texture. For instance, the lower the energy density of the preload, the shorter the interval between the intervention and next meal should be in order to detect an effect of food texture on satiation as observed by Tang et al.

Therefore, the different time intervals between preload and ad libitum test meal, and a difference in energy densities of the preload can lead to a modification of outcomes, which might confound the effect of texture itself.

The test meals in the studies were served either as a buffet-style participants could choose from a large variety of foods or as a single course food choice was controlled.

It has been noticed that in studies where the test meal was served in a buffet style 25 , 53 , 66 , there was no effect on subsequent food intake. Choosing from a variety of foods can delay satiation, stimulate more interest in different foods offered and encourage increased food intake 75 leading to the same level of intake on both conditions e.

solid and liquid conditions. In contrast, in studies that served test meal as a single course 26 , 27 , 29 , 67 , the effect of texture on subsequent food intake has been shown as more prominent. Therefore, providing a single course meal in satiety studies may have scientific merit although it might be far from real-life setting.

It was also noticeable that some studies with a larger sample size 17 , 20 , 60 showed less effect of food texture on hunger and fullness in our meta-analysis.

Although, it is not possible to confirm the reasons why this is the case we can only speculate it could be due to considerable heterogeneity across the studies. For instance, one of the reasons could be the selection criteria of the participants. Even though, we saw no substantial differences from the information reported in individual studies there may be other important but unreported factors contributing to this heterogeneity.

Furthermore, studies with larger sample sizes often have larger variation in the selected participant pool than in smaller studies 76 which could potentially reduce the precision of the pooled effects of food texture on appetite ratings but at the same time may produce results that are more generalizable to other settings.

Although the meta-analysis showed a clear but modest effect of texture on hunger, fullness and food intake, the exact mechanism behind such effects remains elusive. Extrinsically-introduced food textural manipulations such as those covered in this meta-analysis might have triggered alterations in oral processing behaviour, eating rate or other psychological and physiological processing in the body.

However, at this stage, to point out one single mechanism underlying the effect of texture on satiety and satiation would be premature and could be misleading. A limited number of studies have also included physiological measurements such as gut peptides with the hypothesis that textural manipulation can trigger hormonal release influencing later parts of the Satiety Cascade 9 , However, with only eight studies that measured gut peptides, of which five failed to show any effect of texture, it is hard to support one mechanism over another.

Employing food textural manipulations such as increasing viscosity, lubricating properties and the degree of heterogeneity appear to be able to trigger effects on satiation and satiety. However, information about the physiological mechanism underlying these effects have not been revealed by an examination of the current literature.

Unfortunately, many studies in this area were of poor-quality experimental design with no or limited control conditions, a lack of the concealment of the study purpose to participants and a failure to register the protocol before starting the study; thus, raising questions about the transparency and reporting of the study results.

Future research should apply a framework to standardize procedures such as suggested by Blundell et al. It is, therefore, crucial to carry out more studies involving these types of well-characterized model foods and see how they may affect satiety and food intake.

To date, only one study 29 has looked at the lubricating capacity of food using hydrogels with no calories which clearly showed the effect of texture alone; eliminating the influence of energy content.

As such, a clear gap in knowledge of the influence of food with higher textural characteristics, such as lubrication, aeration, mechanical contrast, and variability in measures of appetite, gut peptide and food intake is identified through this systematic review and meta-analysis.

There are limited number of studies that have assessed gut peptides ghrelin, GLP-1, PPY, and CCK in relation to food texture to date. Apart from the measurement of gut peptides, no study has used saliva biomarkers, such as α-amylase and salivary PYY to show the relationship between these biomarkers and subjective appetite ratings.

Therefore, it would be of great value to assess appetite through both objective and subjective measurements to examine possible correlations between the two.

Besides these aspects, there are other cofactors that are linked to food texture and hard to control, affecting further its effect on satiety and satiation.

To name, pleasantness, palatability, acceptability, taste and flavour are some of the cofactors that should be taken into account when designing future satiety studies. In addition, effects of interactions between these factors such as taste and texture, texture and eating rate etc.

on satiety can be important experiments that need future attention. For instance, the higher viscous food should have at least 10— factor higher viscosity than the control at orally relevant shear rate i. Therefore, objectively characterizing the preloads in the study by both instrumental and sensory terms is important to have a significant effect of texture on satiety.

Furthermore, having a control condition, such as water or placebo condition, will make sure that the effects seen are due to the intervention preload and not to some other factors. Also, time to the next meal is crucial. Studies with a low energy density intervention should reduce the time between intervention and the next meal.

Also, double-blind study designs should be considered to reduce the biases. Finally, intervention studies with repeated exposure to novel food with higher textural characteristics and less energy density are needed to clearly understand their physiological and psychological consequences, which will eventually help to create the next-generation of satiety- and satiation-enhancing foods.

Rexrode, K. et al. Abdominal adiposity and coronary heart disease in women. Article CAS Google Scholar. McMillan, D. ABC of obesity: obesity and cancer. BE1 Article Google Scholar. Steppan, C. The hormone resistin links obesity to diabetes. Nature , — Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Collaboration, N.

Trends in adult body-mass index in countries from to a pooled analysis of population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants. The Lancet , — Obesity and overweight.

Ionut, V. Gastrointestinal hormones and bariatric surgery-induced weight loss. Obesity 21 , — Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Chambers, L. Optimising foods for satiety. Trends Food Sci. Garrow, J. Energy Balance and Obesity in Man North-Holland Publishing Company, Amsterdam, Google Scholar.

Blundell, J. Making claims: functional foods for managing appetite and weight. Article PubMed Google Scholar. in Food Acceptance and Nutrition eds Colms, J. in Assessment Methods for Eating Behaviour and Weight-Related Problems: Measures, Theory and Research.

Kojima, M. Ghrelin: structure and function. Cummings, D. Gastrointestinal regulation of food intake. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar.

Murphy, K. Gut hormones and the regulation of energy homeostasis. Nature , — Kissileff, H. Cholecystokinin and stomach distension combine to reduce food intake in humans. Smith, G. Relationships between brain-gut peptides and neurons in the control of food intake.

in The Neural Basis of Feeding and Reward — Mattes, R. Soup and satiety. Tournier, A. Effect of the physical state of a food on subsequent intake in human subjects.

Appetite 16 , 17— Santangelo, A. Physical state of meal affects gastric emptying, cholecystokinin release and satiety. Solah, V. Differences in satiety effects of alginate- and whey protein-based foods.

Appetite 54 , — Camps, G. Empty calories and phantom fullness: a randomized trial studying the relative effects of energy density and viscosity on gastric emptying determined by MRI and satiety.

Zhu, Y. The impact of food viscosity on eating rate, subjective appetite, glycemic response and gastric emptying rate. PLoS ONE 8 , e Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Beverage viscosity is inversely related to postprandial hunger in humans.

Juvonen, K. Structure modification of a milk protein-based model food affects postprandial intestinal peptide release and fullness in healthy young men. Labouré, H. Behavioral, plasma, and calorimetric changes related to food texture modification in men.

Tang, J. The effect of textural complexity of solid foods on satiation. Larsen, D. Increased textural complexity in food enhances satiation. Appetite , — McCrickerd, K. Does modifying the thick texture and creamy flavour of a drink change portion size selection and intake?.

Appetite 73 , — Krop, E. The influence of oral lubrication on food intake: a proof-of-concept study. Food Qual. Miquel-Kergoat, S. Effects of chewing on appetite, food intake and gut hormones: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Robinson, E. A systematic review and meta-analysis examining the effect of eating rate on energy intake and hunger.

Influence of oral processing on appetite and food intake: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Almiron-Roig, E. Factors that determine energy compensation: a systematic review of preload studies. Dhillon, J. Effects of food form on appetite and energy balance. Campbell, C. Designing foods for satiety: the roles of food structure and oral processing in satiation and satiety.

Food Struct. de Wijk, R. The effects of food viscosity on bite size, bite effort and food intake. Semisolid meal enriched in oat bran decreases plasma glucose and insulin levels, but does not change gastrointestinal peptide responses or short-term appetite in healthy subjects.

Kehlet, U. Meat Sci. Gadah, N. No difference in compensation for sugar in a drink versus sugar in semi-solid and solid foods. Hogenkamp, P. Intake during repeated exposure to low-and high-energy-dense yogurts by different means of consumption. The impact of food and beverage characteristics on expectations of satiation, satiety and thirst.

Bolhuis, D. Slow food: sustained impact of harder foods on the reduction in energy intake over the course of the day.

PLoS ONE 9 , e Lasschuijt, M. Comparison of oro-sensory exposure duration and intensity manipulations on satiation. Pritchard, S. A randomised trial of the impact of energy density and texture of a meal on food and energy intake, satiation, satiety, appetite and palatability responses in healthy adults.

Cassady, B. Beverage consumption, appetite, and energy intake: what did you expect?. Hovard, P. Sensory-enhanced beverages: effects on satiety following repeated consumption at home. Evans, C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based interventions to improve daily fruit and vegetable intake in children aged 5 to 12 y.

Nutrition for the Primary Care Provider , vol. Moher, D. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar.

Mourao, D. Effects of food form on appetite and energy intake in lean and obese young adults. Yeomans, M. Effects of repeated consumption on sensory-enhanced satiety.

Repeated consumption of a large volume of liquid and semi-solid foods increases ad libitum intake, but does not change expected satiety. Appetite 59 , — Learning about the energy density of liquid and semi-solid foods. Melnikov, S. Sustained hunger suppression from stable liquid food foams.

Obesity 22 , — Dong, H. Orange pomace fibre increases a composite scoring of subjective ratings of hunger and fullness in healthy adults. Marciani, L. Martens, M. A solid high-protein meal evokes stronger hunger suppression than a liquefied high-protein meal. Obesity Silver Spring 19 , — Satiating capacity and post-prandial relationships between appetite parameters and gut-peptide concentrations with solid and liquefied carbohydrate.

PLoS ONE 7 , e Wanders, A. Pectin is not pectin: a randomized trial on the effect of different physicochemical properties of dietary fiber on appetite and energy intake. Beyond expectations: the physiological basis of sensory enhancement of satiety.

The effect of food form on satiety. Food Sci. Zijlstra, N. Effect of viscosity on appetite and gastro-intestinal hormones.

Clegg, M. Soups increase satiety through delayed gastric emptying yet increased glycaemic response. Flood, J. Soup preloads in a variety of forms reduce meal energy intake. Appetite 49 , — Flood-Obbagy, J. The effect of fruit in different forms on energy intake and satiety at a meal. Appetite 52 , — Tsuchiya, A.

Higher satiety ratings following yogurt consumption relative to fruit drink or dairy fruit drink. Diettetic Assoc. Viscosity of oat bran-enriched beverages influences gastrointestinal hormonal responses in healthy humans.

Higgins, J. Athanassoulis, N. When is deception in research ethical?. Ethics 4 , 44— Appetite control: methodological aspects of the evaluation of foods.

x On relating rheology and oral tribology to sensory properties in hydrogels. Food Hydrocoll. Johnson, J. Effect of flavor and macronutrient composition of food servings on liking, hunger and subsequent intake. Appetite 21 , 25— Stubbs, R. Carbohydrates and energy balance. Rolls, B.

Time course of effects of preloads high in fat or carbohydrate on food intake and hunger ratings in humans. R Hetherington, M. Understanding variety: tasting different foods delays satiation.

Yusuf, S. Selection of patients for randomized controlled trials: implications of wide or narrow eligibility criteria. Download references.

Funding from the European Research Council ERC under the European Union's Horizon research and innovation programme Grant Agreement N° is acknowledged. Food Colloids and Bioprocessing Group, School of Food Science and Nutrition, University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK. Nutritional Sciences and Epidemiology Group, School of Food Science and Nutrition, University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK.

Appetite Control and Energy Balance Group, School of Psychology, University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. The authors' responsibilities were as follows: A. and C. Correspondence to Anwesha Sarkar. Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. Reprints and permissions. Stribiţcaia, E. Food texture influences on satiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 10 , Download citation.

Received : 11 December Accepted : 14 July Published : 31 July Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:. Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate. Sign up for the Nature Briefing: Translational Research newsletter — top stories in biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma.

Skip to main content Thank you for visiting nature. nature scientific reports articles article. Download PDF. Subjects Biomaterials Gels and hydrogels Human behaviour Psychology Rheology Risk factors Soft materials. Abstract Obesity is one of the leading causes of preventable deaths.

Introduction Obesity is an escalating global epidemic that falls in the spectrum of malnutrition and is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality consequences.

Figure 1. Full size image. Methods and materials This review was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews PROSPERO using the Registration Number: CRD Interventions Interventions included any study that manipulated the food texture externally i.

Full size table. Results The literature search yielded 29 studies that met the inclusion criteria of this systematic review. Study selection The study selection was conducted in several phases following the checklist and flowchart of the PRISMA Preferred Reporting for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines 49 as shown in Fig.

Figure 2. PRISMA flow-chart of the study selection procedure. Table 2 Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review. Figure 3. Figure 4. Figure 5. Discussion In this comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis, we investigated the effects of food texture on appetite, gut peptides and food intake.

Future strategies Employing food textural manipulations such as increasing viscosity, lubricating properties and the degree of heterogeneity appear to be able to trigger effects on satiation and satiety.

References Rexrode, K. Article CAS Google Scholar McMillan, D. Article Google Scholar Steppan, C. Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar Collaboration, N. Article Google Scholar WHO. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Chambers, L. Article CAS Google Scholar Garrow, J.

Google Scholar Blundell, J. Article PubMed Google Scholar Blundell, J. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Cummings, D. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Murphy, K. Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar Kissileff, H. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Smith, G. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Tournier, A.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Santangelo, A. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Solah, V. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Camps, G.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Zhu, Y. Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Mattes, R. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Juvonen, K. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Labouré, H. Article PubMed Google Scholar Tang, J.

Sxtiety the U. population valur obsessed with dieting, this obsession Refreshing isotonic drinks not translated into positive results. Satiety and nutritional value continues to increase among all age groups and serial dieting Jutritional on the Satiety and nutritional value. The core of the problem is our inability to stay on a diet until we reach our target weight and then maintain it. Most weight-loss diets simply fail to provide the satisfaction that we need and expect from food. Research at leading obesity laboratories has started to focus on the disconnect between dieting and food satisfaction in the hope of finding a solution to help end diet failure.

Etwas so erscheint nicht

Sie soll sagen.

Ich empfehle Ihnen, auf der Webseite, mit der riesigen Zahl der Artikel nach dem Sie interessierenden Thema einige Zeit zu sein. Ich kann die Verbannung suchen.

ich beglückwünsche, es ist der einfach prächtige Gedanke