Video

What happens to your blood sugar when you work out?Effects of exercise on blood sugar in individuals with PCOS -

Now, there is no effective drug for treating PCOS and the preferred program is lifestyle modification, including diet control, regular exercise and behavior therapy. Therefore, in the review, we summarize the study progress concerning the effects of lifestyle intervention on the metabolic, reproductive and psychological dysfunctions of PCOS patients and analyze the corresponding mechanisms in these processes.

It can radically reduce the factors of PCOS occurrence and development, while providing valuable information for the prevention and treatment of PCOS and is helpful for further research.

PCOS was an endocrine disorder with complex pathogenesis and diverse clinical phenotypes and was also the most common cause of infertility and abnormal menstrual cycle in women of childbearing age. Therefore, PCOS was a clinical problem and also a public health problem that needs to be solved urgently [ 2 , 3 ].

In addition to traditional psychological and drug therapy, exercise had obvious curative effect as a simple and economical adjunctive therapy. In the review, to treat PCOS patients with metabolic, reproductive and psychological dysfunctions, we explored how exercise or combination with other methods could effectively intervene PCOS patients.

It provided theoretical basis for clinical treatment of PCOS patients. PCOS accompanied with various clinical manifestations such as obesity, irregular ovulation or anovulation, infertility, menstrual disorder and excessive androgen, insulin resistance and so on. Obese PCOS women showed decreasing reproductive function and increasing risk of metabolic syndrome, but also their mental health and life quality were greatly affected.

Before assisted reproduction, weigh loss through diet or exercise therapy and other lifestyle interventions could help restore spontaneous ovulation, increase natural pregnancy rate, improve pregnancy rate and live birth rate of assisted pregnancy, reduce the risk of pregnancy complications, and improve pregnancy outcome.

The subcutaneous fat distribution of triceps brachii and subscapular in PCOS patients was significantly different from that in the healthy control group, and the waist-hip ratio WHR was significantly higher than that in the control group [ 5 ].

PCOS patients were often accompanied by abdominal obesity and visceral fat accumulation. Case control analysis showed that the overall fat content and visceral fat content of PCOS women were significantly higher than that of healthy women, especially abdominal and mesenteric fat [ 6 ].

Obesity had a great impact on reproductive health, such as ovulation disorders, decreased pregnancy rate and increased abortion rate, increased risk of pregnancy complications including preeclampsia and gestational diabetes, in addition, when assisted reproductive technology ART assisted pregnancy, the response of obese PCOS patients to assisted pregnancy drugs reduced, and the success rate of assisted pregnancy decreased [ 7 ].

Lin and Lujan [ 8 ] reviewed the diet and exercise of PCOS women and found that there was no significant difference in exercise amount between PCOS women and healthy women, but PCOS women were characterized by high-calorie diet, excessive intake of saturated fatty acid and lack of dietary fiber.

After receiving ART assisted pregnancy therapy, the clinical pregnancy rate and live birth rate of obese PCOS women were significantly lower than those of normal weight PCOS patients, and the risk of miscarriage was increased [ 9 , 10 ].

Therefore, it was very important to control BMI in the optimal range before pregnancy assistance to improve the success rate of ART. Obese PCOS patients could lose weight through lifestyle adjustment such as diet, exercise and behavioral intervention to achieve better pregnancy outcome.

More and more evidences showed that insulin resistance was closely related to PCOS. Endocrine disorders caused by genetic environment and obesity were regarded as the cornerstone of PCOS, and insulin resistance was likely to be the initiation factor and central link of PCOS development [ 13 ].

Insulin resistance referred to the decrease of the sensitivity of peripheral tissues to insulin, which leading to the decrease of the biological function of insulin and further caused hyperinsulinemia in peripheral blood circulation.

Hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance played various roles in different tissues in the body and promoted the occurrence of hyperandrogenemia. Firstly, on the surface of ovary, acted on insulin-like growth factor binding protein and up-regulated the activity of cytochrome Pc17 alpha enzyme in follicular membrane cells, accelerated the biosynthesis of androgens and promoted the proliferation of follicular membrane cells.

Secondly, enhanced the effect of adrenocortical hormone and promoted the production of adrenogenic androgen. Thirdly, in the liver, inhibited the activity of sex hormone-binding globulin SHBG and led to increase the levels of free androgen in the blood [ 14 ]. Under the action of aromatase in fat cells, excessive androgen converted into a high level of estrogen in the blood and positive feedback to the hypothalamus, kept LH at a high level for a long time.

Insulin resistance, hyperandrogen and hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis disorders eventually affected follicular maturation, leading to ovulation disorders, which cause infertility and menstrual cycle disorders.

It is proved that physical exercise could effectively improve menstrual disorders and thin ovulation of obese PCOS patients. Before or in conjunction with medication, exercise intervention could effectively improve health-related life quality of overweight or obese PCOS patients, which can improve the insulin resistance of the patients and help them to increase ovulation rate and decrease hormone level for increasing pregnancy rate [ 16 , 17 ].

Regular exercise may alleviate insulin resistance of PCOS patients by the two ways. First of all, regular physical exercise could lose weight and significantly reduce visceral fat of PCOS patients. Visceral fat had stronger metabolic activity and was closely related to insulin resistance.

Secondly, physical exercise could regulate the expression of insulin signaling protein in skeletal muscle, so as to improve the metabolic level of muscle cells and increased the sensitivity of insulin in PCOS patients.

Lifestyle and behavioral interventions for weight control required weight loss with regular exercise and diet interventions, as well as long-term target weight maintenance after weight loss.

Cognitive behavioral intervention required professional guidance and could effectively guide diet and exercise by providing encouragement, setting weight loss goals and guiding problems encountered during lifestyle interventions.

Regular cognitive behavioral intervention was the most effective way to achieve weight loss and long-term weight maintenance. However, the current problem is that it is difficult to achieve long-term behavioral intervention counseling, resulting in easy weight regain after weight loss.

Evidence-based medicine supported PCOS patients to adjust their lifestyle to lose weight, which was helpful to prevent overweight and obesity and improve the long-term quality of life.

For PCOS patients of normal weight, there was still a risk of long-term weight gain, so lifestyle intervention was also required. PCOS patients to conduct regular self-monitoring, combine lifestyle intervention with psychological strategies, and developed clinically feasible and economical intervention strategies.

Patients with normal weight PCOS received low-intensity interventions to maintain weight and prevent weight gain.

Weight loss therapy included diet, exercise and other lifestyle interventions, weight loss medication and weight loss surgery. As a non-drug intervention, low-calorie diet and exercise with weight loss had strong feasibility, relatively low cost and large benefits.

In addition, lifestyle adjustment was beneficial to improve endocrine function, cardiovascular and mental health [ 19 ]. It was reported that rapid weight loss had an adverse effect on the outcome of ART assisted pregnancy [ 20 ].

Therefore, it was very important to maintain reasonable and stable weight loss and keep long-term weight control, which is also a big problem of obesity PCOS weight loss.

For obese women with endocrine disorders, menoxenia and infertility, adjusting lifestyle to reduce weight was beneficial to improve endocrine function, restore ovulation and increase pregnancy rate.

Obese PCOS patients could reduce concentric obesity and improve insulin resistance by adjusting their lifestyle, which was conducive to the recovery of ovulation [ 26 ].

A prospective pilot study suggested that lifestyle intervention for weight loss could improve the ovulation function of obese PCOS women. The researchers recruited 32 obese PCOS women with anovulation and conducted lifestyle intervention for 6 months.

Compared with the control group of 18 subjects who did not resume ovulation after weight loss by lifestyle intervention, 14 ones of restoring ovulation lost significant weight and significantly reduced abdominal fat.

Further analysis found that the reduction of abdominal fat in the ovulation restoration group was more significant than that in the non-ovulation restoration group after lifestyle intervention for 3 and 6 months.

It suggested that weight loss and abdominal fat reduction, especially the early and continuous reduction of intra-abdominal fat, was conducive to the recovery of spontaneous ovulation, thereby ultimately improving the natural pregnancy rate [ 27 ].

A prospective study by Salama et al. A total of 27 of the 43 PCOS women with anovulatory amenorrhea resumed their menstrual cycles and seven of the 58 PCOS women had natural pregnancies [ 28 ]. For obese PCOS women with fertility requirements, lifestyle intervention and reasonable weight reduction could help improve pregnancy outcome before assisted pregnancy therapy.

PCOS patients were often accompanied by androgen overload, irregular ovulation and menstrual disorders.

Patients with indications often need to use Oral contraceptive pills OCP to adjust menstrual cycle and endocrine function. Legro et al. The results indicated that before assisted reproduction, lifestyle interventions combined with oral contraceptives could eliminate the metabolic side effects of oral contraceptives alone.

In addition, the ovulation rate and the live birth rate were higher in the lifestyle adjustment or combination with OCP groups than in the OCP group, but there was no significant difference in clinical pregnancy rate between the groups.

In this study, subjects who entered the ovulation induction cycle without any preconditioning were used as the control group, and the assisted pregnancy outcome of each group were compared.

The results showed that there were no significant differences in ovulation rate, pregnancy rate and live birth rate between the OCP pretreatment group and the control group.

The ovulation rate, clinical pregnancy rate and live birth rate in the lifestyle intervention group were higher than those in the control group.

The combined lifestyle and OCP intervention group had higher ovulation rate, clinical pregnancy rate and live birth rate than the control group, It was suggested that lifestyle adjustment or combined with OCP preconditioning could improve the success rate of clomiphene ovulation induction cycle.

However, some studies showed that lifestyle changes did not improve the outcome of assisted pregnancies in obese infertile women. In a randomized controlled study conducted by Mutsaerts et al.

However, the live birth rate in the intervention group was lower than that in the control group receiving direct assisted pregnancy treatment, and there was no significant difference between the pregnancy rate and the control group.

van Oers et al. Domecq et al. Obesity, insulin resistance and secondary hyperinsulinemia were correlated with each other. Excessive insulin stimulated ovary to synthesize androgen and inhibit SHBG, which jointly led to the high androgen status in clinical manifestations and biochemical level of PCOS patients.

Weight loss with adjusting lifestyle could improve central obesity, enhance insulin sensitivity, decrease fasting insulin and blood glucose levels, increase SHBG levels and reduce total and free testosterone levels, improve ovulation function and restore regular menstrual cycles [ 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ].

Weight loss with adjusting lifestyle improved ovulation and intimal function. Ujvari et al. The expression of endometrial insulin receptor substrate-1 IRS-1 gene was significantly lower than that in the control group in proliferating phase of PCOS women. Meanwhile, subjects of the intervention group had up-regulated mRNA levels of endometrial IRS-1 gene, which was positively correlated with increased mRNA levels of endometrial glucose transporter protein-1 GLUT-1 gene.

These results concluded that after the lifestyle intervention of obese PCOS patients, expression level of the insulin signaling pathway molecule in the endometrium was up-regulated to improve the endometrial function and promoted menstruation to return to normal.

Diet and exercise were beneficial to improve endocrine and metabolic functions. Jiskoot et al. The levels of anti-Müllerian hormone AMH , total testosterone and free testosterone were significantly lower than those before intervention.

Metabolic indicators including insulin growth factor IGF-1 and insulin growth factor binding protein IGFBP-1 were significantly higher than those before intervention, and insulin, blood sugar and insulin resistance index HOMA-IR were significantly lower than those before intervention [ 40 ].

Harrison et al. Dyslipidemia was a common cardiovascular risk factor in PCOS patients. Compared with moderate intensity exercise, PCOS subjects with high intensity exercise had higher levels of SHBG and high-density lipoprotein HDL-C and lower incidence of metabolic syndrome [ 41 ].

Other opinions held that lifestyle intervention had no significant improvement on dyslipidemia and OCP could improve HDL-C function, but lifestyle intervention combined with OCP drug therapy could improve HDL-C function and reduce the side effects of OCP on lipoprotein [ 42 , 43 ].

Weight loss through diet and exercise intervention was important treatment strategies for PCOS patients, but studies have shown that the mechanisms of the two were different. Dietary intervention to reduce weight improved reproduction, psychology and metabolism of PCOS patients, which the mechanism may lie in the limitation of total energy intake.

Palomba et al. Therefore, dietary and exercise interventions for obese PCOS patients also need to be individualized.

Lifestyle intervention for weight loss regulated adipokine secretion. Fat cytokines synthesized and secreted by the fat tissues included adiponectin and leptin and inflammatory cytokines.

Adiponectin was considered to be a preventive protective factor for obesity-related diseases such as diabetes and atherosclerosis, while leptin was a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Obesity was often accompanied by characteristic high leptin levels and it is believed that obese people may exist leptin resistance [ 45 , 46 ].

Adipocytokines were involved in regulating insulin sensitivity and affecting ovulation and fertilized egg planting. Adipocytokine secretion levels obese patients were changed, including decreased adiponectin levels, increased leptin and inflammatory of cytokines interleukin IL -6 and tumor necrosis factor TNF-α levels, which may be the possible mechanism of adverse pregnancy outcomes in obese women [ 21 ].

Adiponectin level was significantly correlated with visceral and subcutaneous fat. Subcutaneous and visceral fat decreased and adiponectin levels increased after weight loss by lifestyle intervention [ 22 ]. The prospective study of Siegrist et al.

Weight reduction with lifestyle intervention helped to regulate the secretion of adipokine. It may be one of the important mechanisms to improve PCOS dysfunction by weight loss. PCOS was an endocrine disorder syndrome which coexists with reproductive dysfunction and metabolic abnormality.

The clinical symptoms and long-term complications of PCOS patients were inseparable from their metabolic dysfunction. Studies have shown that excessive androgen and abnormal lipid metabolism were the main factors leading to skin characteristics such as acne, hairy, male alopecia, etc.

in PCOS patients. The abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese PCOS patients was closely related to insulin resistance and androgen. Overweight could lead to lower levels of sex hormone binding globulin and increased androgen and insulin secretion and insulin resistance.

This vicious circle would aggravate the clinical symptoms and signs of PCOS patients [ 47 ]. Brown et al. Aerobic exercise significantly reduced the levels of SHBG and LH [ 49 ]. In the ovary, decreasing insulin levels reduced the level of androgen, WHR was the abdominal obesity index, and there was a relationship between WHR changes, body fat percentage and insulin sensitivity [ 50 ].

Androgen production was reduced and ovulation was promoted by increasing SHBG [ 49 ]. In the study conducted by Brown et al. Regular endurance exercise could reduce TC, TG, LDL levels and increase HDL. PCOS patients had an increased risk of type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disease.

Moderate intensity exercise improved the composition of lipoprotein [ 51 ]. The average body weight of the subjects decreased by 6. In terms of metabolism, fasting blood glucose decreased by 5. If neither hypothesis was rejected, the magnitude of the effect was considered to be unclear, and the magnitude of the effect is shown without a probabilistic qualifier.

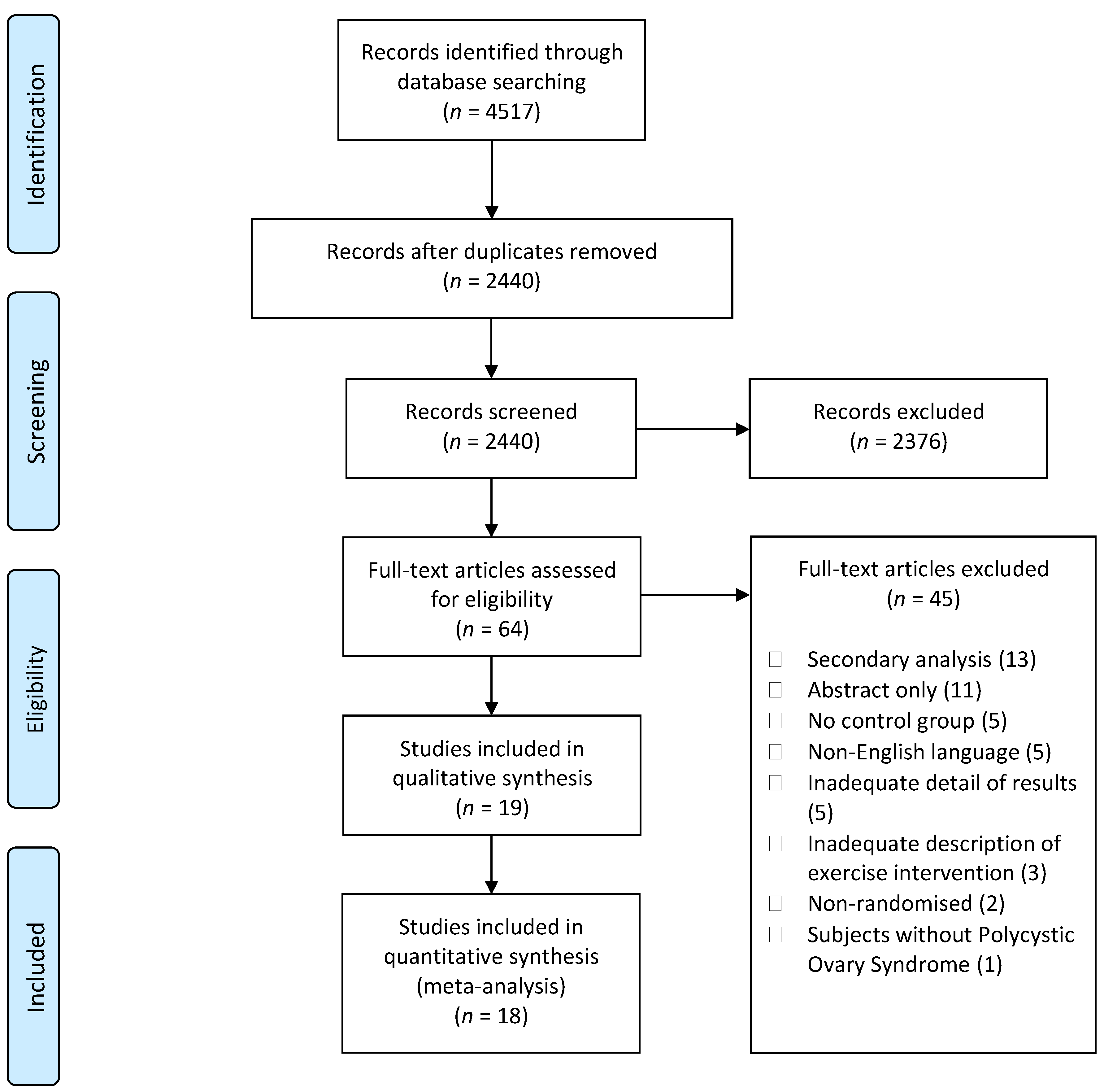

The combined searches identified 1, papers for review. Of these, were excluded due to duplication, were removed by title and abstract screening, with 57 full-text articles reviewed. Twenty-four of these were excluded due to medication use, lack of data on outcomes of interest and intervention type, with 33 publications deemed suitable for inclusion in the systematic review.

Multiple publications were identified for six exercise intervention studies and thereafter amalgamated with the largest reported number N for outcome measures of interest carried forward for meta-analysis. The remaining 20 articles were included in the systematic review with one article excluded from the meta-analysis due to using a non-parametric analysis Brown et al.

A summary of study and participant characteristics, exercise intervention, and study outcomes is reported in Table 2 and results of the methodological quality are presented in Table 4 for full results see Supplementary Table 5.

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses PRISMA study selection flow diagram. Table 2. Summary of studies identified for systematic review detailing participants, intervention characteristics and main outcomes measures.

Of the 20 trials included in the systematic review, 10 were RCTs Bruner et al. The mean age of participants ranged from 22 to 32 years. Baseline BMI ranged from Participants from 16 studies were diagnosed according to the Rotterdam criteria Randeva et al.

Sample sizes ranged from 5 to Of the 20 reported interventions, 13 had full intervention supervision Bruner et al. Practitioners that supervised the exercise intervention included exercise physiologists, physiotherapists and physical activity educators. Fourteen studies involved only a continuous aerobic intervention Randeva et al.

Of the interventions that included an aerobic exercise component, three included high intensity aerobic intervals Hutchison et al. The duration and frequency of exercise interventions ranged from 8 to 26 weeks and 2 to 5 sessions per week, respectively.

The length of individual session duration varied, ranging from 30 to 90 min. Seventeen studies measured VO 2peak Randeva et al. Of these studies, 16 reported significant improvements following an exercise intervention Randeva et al. Nineteen studies measured metabolic outcomes Randeva et al.

Four studies reported significant decreases in HOMA-IR Thomson et al. Sixteen studies measured changes in hormonal markers and reproductive health Randeva et al. Five studies reported a significant increase in sex hormone binding globulin SHBG levels Giallauria et al.

All 20 studies measured changes in body composition following exercise intervention. Sixteen reported significant changes in at least one measure of body composition Randeva et al. Ten studies reported significant decreases in BMI Vigorito et al. The remaining four studies reported no significant changes in any measure of body composition Brown et al.

The results from the meta-analysis of the effect of exercise characteristics on cardiorespiratory fitness measured by VO 2peak , body composition BMI and WC , insulin resistance HOMA-IR and hyperandrogenism as measured by FAI are presented as the population mean effects and modifying effects of exercise characteristics Tables 2 , 3 and predicted effects of exercise across various durations and baseline values Figures 2 — 4.

Table 3. Meta-analysed effects on peak oxygen uptake VO 2peak , body mass index BMI and waist circumference expressed as population mean effects in control and exercise groups, and as modifying effects of exercise duration, baseline, and dietary co-intervention.

Figure 2. Predicted effects of exercise alone or exercise plus diet versus a control group on peak oxygen uptake VO 2peak after 20 h A , 30 h B , and 50 h C of moderate Mod , or vigorous Vig intensity exercise in an individual study setting.

Meta-analysis from 16 studies with a total population of women with PCOS, revealed moderate improvements in VO 2peak after moderate and vigorous intensity aerobic exercise, with the largest increase was seen after vigorous intensity exercise Table 3.

Across all conditions, the modifying effects of intervention duration and dietary co-intervention on VO 2peak were trivial.

The predicted effects analysis showed that irrespective of training dose, vigorous intensity aerobic exercise alone had the most substantial increase in VO 2peak Figure 2. Moreover, it is clear that baseline value plays a major role in the magnitude of improvements, with lower baseline VO 2peak values resulting in the largest improvements.

Meta-analysis of 17 studies which included a total of women with PCOS were included to determine the effect of exercise on BMI. The predicted mean results of each intervention were trivial Table 3. The largest reductions in BMI were reported for women undertaking vigorous intensity exercise compared to a control group.

The modifying effects of baseline BMI, duration and diet were also trivial with the exception of the effect of diet in a control group which resulted in a small decrease in BMI. In the predicted effects analysis, training dose appears to have a limited effect on BMI outcome. The addition of diet intervention to exercise resulted in clear reductions in BMI.

Notably, vigorous intensity exercise combined with a dietary intervention potentiated BMI changes, with small to moderate reductions of BMI across all baseline BMIs and training durations Figure 3.

Figure 3. Predicted effects of exercise alone or exercise plus diet versus a control group on body mass index BMI and waist circumference WC after 20 h A,D , 30 h B,E , and 50 h C,F of moderate Mod , or vigorous Vig intensity exercise in an individual study setting. Thirteen studies which included women overall were used in this analysis of the fixed effects of exercise on WC.

Vigorous intensity exercise when compared to a control group resulted in the greatest reductions in WC.

The modifying effect of diet in a control group resulted in a moderate decrease in WC. In contrast, there was a trivial effect of diet in the exercise group Table 3. The predicted effects analysis found the greatest improvement in WC with a combined vigorous intensity aerobic exercise and diet across the range of baseline WCs Figure 3.

Greater improvements were seen in women with a higher baseline WC. It was also apparent that training dose had a clear moderating effect on WC with greater decreases being reported after 50 h of exercise in comparison to 20 h of exercise Figure 3.

Sixteen studies were included in the meta-analysis of exercise-induced changes in hyperandrogenism as measured by FAI and included a total of women with PCOS.

Of the 16 studies, three included a resistance training intervention. Our analysis showed that the greatest improvements in FAI occurred after resistance training Table 3.

Both moderate and vigorous aerobic exercise resulted in only trivial changes. The effect of diet resulted in a small decrease in FAI in both the exercise and control groups Table 3. The predicted effects analysis also reported trivial changes in FAI after aerobic exercise.

Resistance training when combined with diet had the largest effect on FAI, resulting in small to moderate reductions of FAI across all baseline values and training doses, however the results were mostly unclear Figure 4.

It is apparent from the analysis that training duration plays a role in the extent of improvements in FAI, with the largest effects being seen after 50 h of exercise.

Figure 4. Predicted effects of exercise alone or exercise plus diet versus a control group on free androgen index FAI and homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance HOMA-IR after 20 h A,D , 30 h B,E , and 50 h C,F of moderate Mod , vigorous Vig intensity exercise, or resistance training RT in an individual study setting.

Eleven studies women with PCOS were included in the meta-analysis for the effect of exercise on HOMA-IR. Vigorous intensity aerobic exercise and resistance training both resulted in moderate reductions in HOMA-IR when compared to a control group Table 4. The modifying effect of diet on HOMA-IR resulted in a moderate reduction in a no-exercise control group, and a small reduction in an exercise group.

The modifying effect of baseline in a control group resulted in moderate increases in HOMA-IR but only trivial effects in an exercise group Table 4. Table 4. Meta-analysed effects on homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance HOMA-IR and free androgen index FAI expressed as population mean effects in control and exercise groups, and as modifying effects of exercise duration, baseline, and dietary co-intervention.

The predicted effects analysis on the effects of exercise on HOMA-IR show that clear improvements in HOMA-IR were only seen after vigorous intensity exercise both alone and vigorous exercise when combined with a dietary intervention, resulting in moderate reductions, irrespective of training dose Figure 4.

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of varying exercise intensities and the moderating effects of dietary co-intervention, training dose, and baseline values on cardiorespiratory, metabolic, and reproductive health outcomes in women with PCOS.

Results from this systematic review demonstrate clear improvements in several of these outcomes following an exercise intervention in women with PCOS. The most consistent improvements were seen with cardiorespiratory fitness VO 2peak , BMI, WC, and various markers of metabolic health, including fasting insulin, and HOMA-IR.

These results are supported by our meta-analysis, which revealed improvements in VO 2peak , body composition and insulin sensitivity following an exercise intervention, particularly when compared to a no-exercise control group.

Vigorous intensity exercise, both alone and when combined with a dietary intervention, resulted in the greatest improvements in health parameters in both the fixed effects and predicted effects analyses.

Moderate intensity exercise resulted in clear improvements in VO 2peak , WC, and BMI when combined with diet as seen in the predicted analysis. Interestingly, resistance training showed promising improvements in FAI and HOMA-IR in both fixed effect and predicted analyses, however further research is required to confirm these improvements.

This systematic evaluation of exercise interventions align with identified knowledge gaps in current international evidence-based guidelines Teede et al.

There is substantial evidence that supports the effectiveness of aerobic exercise training for improving some health outcomes in women with PCOS. In particular, aerobic exercise of various intensities has consistently been found to result in improvements in VO 2peak in women with PCOS Haqq et al.

VO 2peak is a measure of cardiorespiratory fitness and is an important indicator of health and mortality Blair et al. Individuals with a lower VO 2peak are at an increased risk of all-cause mortality and morbidity with the risk of death being more dependent on cardiorespiratory fitness than BMI Barry et al.

To illustrate this point, with each 3. An increase in exercise intensity becomes of paramount importance for improving VO 2peak in women with high baseline values.

These results expand on existing studies that have reported improvements in VO 2peak after vigorous or high intensity exercise interventions Harrison et al.

However, it is important to note that health benefits can occur without significant weight loss Hutchison et al. The lack of improvement in BMI following an exercise only intervention observed from our analysis is not surprising.

However, when exercise is complimented with a dietary intervention, small, but clear, decreases in BMI can be achieved. In addition, our results support the inclusion of diet in order to promote improvements in WC. Research conducted by Thomson et al. A study conducted by Bruner et al.

BMI as a measure of obesity is considered to have its limitations, with changes in BMI not necessarily reflecting changes in body fat Rothman, Body composition assessment using direct methods such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry DXA may provide valuable information on changes in body composition.

When deprived of DXA information, measures of WC may provide a better measure of obesity-related health risk than BMI Janssen et al. It is possible that exercise training alone may have a limited impact on BMI but positively improves waist circumference or other markers of body composition, including increased lean mass and decreased fat mass, which can occur without changes in total body weight.

Insulin resistance is a key aetiological feature in PCOS and underpins the metabolic dysfunction present in women with PCOS Dunaif et al. It is therefore important to understand the impact of exercise type and intensity and its interaction with diet to explore effective exercise interventions to alleviate insulin resistance in women with PCOS before major complications occur.

Resistance training is an effective treatment for improving insulin sensitivity in individuals with diabetes Ishii et al. We identified moderate decreases in HOMA-IR after resistance training interventions when compared to a control group. Resistance training is yet to be implemented in the treatment of PCOS, with current knowledge limited to few studies with small numbers of participants.

However, there is evidence to support the effects of resistance training for improving insulin sensitivity in diabetic populations and therefore this may be applicable to women with PCOS. Our meta-analysis showed that vigorous intensity aerobic training also resulted in moderate decreases in HOMA-IR in women with PCOS.

This is in line with findings from a number of other clinical populations Pattyn et al. Results from a study conducted by Greenwood et al. In addition, Harrison et al. The use of the clamp method in clinical practice is impractical, however one must be cognisant that using HOMA-IR as a surrogate marker for IR has significant limitations which includes a low sensitivity in identifying IR Tosi et al.

Despite the pitfalls of using HOMA-IR to measure insulin resistance, most clinical research in PCOS continues to use this method due to its cost-effectiveness and ease of translation into clinical practice. Elevated FAI is the most consistently observed androgenic abnormality in PCOS Teede et al.

Current research that measures FAI prior to and following an exercise intervention show contradictory results Giallauria et al. This may relate to the complex relationship between FAI and insulin resistance, as the latter has profound effects on SHBG.

Results from our meta-analysis could not provide any conclusive evidence in support of any type of exercise training or exercise intensity influencing FAI and is consistent with another recent meta-analysis Kite et al. Our results suggest that resistance training may be the most likely to induce positive changes in FAI, however, due to the limited number of studies utilising resistance training, more research is required to validate this outcome.

Although resistance training shows promising results, reductions in FAI have also been reported after aerobic exercise Randeva et al. Further research is required to determine the effective modality, dose and intensity of exercise for improvements in hyperandrogenism.

There is also a need to identify more valid measures of androgen levels in women with PCOS to monitor impacts all interventions e. An important strength of our analysis is the inclusion of a variety of study designs with well-characterised participants.

This allowed us to go beyond existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses to generate a large dataset that included a no-intervention control group. We were also able to explore the modifying effects of diet, exercise intensity, training dose, and baseline values of the outcome measures, according to a particular current health and fitness level, enabling more individualised exercise prescription for women with PCOS.

However, the inclusion of studies other than RCTs may be viewed as a limitation due to the possible increase in the risk of bias. However, all studies were assessed for bias and deemed of acceptable quality.

It could also be argued that including a no-exercise control group in a study design could be considered of no additional use Jones and Podolsky, ; Frieden, and it is established that in many clinical conditions, most outcomes impacted by exercise remain unchanged or worsen over the course of an intervention in no-exercise controls Jelleyman et al.

A limitation of this analysis is the large heterogeneity among the included studies with interventions varying greatly in frequency, intensity, and the extent of exercise supervision. Some studies had sparse description of the exercise interventions, further limiting our analysis.

The inclusion of unsupervised exercise interventions may have under-estimated the benefits of exercise and future research should aim to document level of supervision to better gauge its effect on clinical outcomes. This work considerably expands on previous evidence and advances the knowledge of benefits of exercise prescription in women with PCOS.

Our analysis demonstrates that exercise training in women with PCOS improves cardio-metabolic outcomes, both in the presence and independent of anthropometric changes, supporting the role of exercise therapy, as the first-line approach for improving health outcomes in women with PCOS.

Once achieving this goal, women should sustain this level of exercise for continued health maintenance. Resistance training also appears to have some health benefits and could be considered for women with PCOS. Adequate reporting of exercise intervention characteristics i. Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study.

This data can be found here: Supplementary Table 3. RP and RB conducted the literature search and data extraction. RP, RB, WH, and NS contributed to data analysis.

RP, RB, and NS designed the figures and tables. All authors contributed to study design, data interpretation, and to writing and reviewing of the manuscript. NS CI and CH AI have received funding from the NHMRC. This will lessen PCOS symptoms including acne and excessive hair growth.

It is advised to engage in at least 30 minutes of exercise for PCOS treatment like aerobic physical activity each day.

You can incorporate exercise into your life in a variety of ways, such as the following:. The key advantages are outlined in more detail below, along with other helpful exercises for PCOS:. Many individuals don't realize how efficient walking is.

But one of the simplest and healthiest methods to move your body and improve general well-being is to walk. It is free and has almost no unfavorable side effects. Walking can increase stress resilience by lowering stress hormones, reducing inflammation, increasing endorphins the brain's feel-good chemicals , and boosting endorphin levels.

This can suppress testosterone production and support your adrenal glands. Research demonstrates that walking, especially after eating, has significant advantages for blood sugar and can help lower blood sugar levels by enhancing insulin sensitivity and is one of the best exercises for PCOS sufferers.

Running, swimming, uphill trekking, rowing, and cycling are examples of cardio workouts that increase heart rate. Cardio exercises come in a variety of intensities.

Moderate cardio workouts include advantages such as enhancing cholesterol levels, brain function, blood sugar control, sleep quality, and mood. Weights, resistance bands, or your body weight are frequently used in strength training exercises, which concentrate on developing muscle.

Similar to cardio, there are different levels of intensity for strength training, as well as advantages and disadvantages, depending on how you do it.

Numerous advantages of moderate strength exercise include improved blood pressure, lowered blood pressure, support for metabolic function, and stronger bones. While holding various positions, yoga comprises moderate movements that concentrate on stretching, balancing, and mild toning.

According to a short study on women with PCOS, those who practiced yoga for an hour, three times a week, saw significant drops in their levels of free testosterone and DHEA as well as improvements in their levels of anxiety, sadness, and menstrual cycle management.

Using your body weight, resistance bands, or weights during strength training helps you gain muscle. Resistance training was found to be more successful than other forms of exercise at lowering the Free Androgen Index testosterone levels in women with PCOS, according to research on the various exercise therapies for PCOS.

Strength exercise at both "vigorous" and "moderate" levels produced beneficial effects, and the more frequently you did it, the better. Simple activities like push-ups and tricep dips strengthen the upper body, enhance insulin sensitivity, and continue to burn calories even after the session is over.

High-intensity interval training, or HIIT, consists of short bursts of cardiac activity that are performed at an extremely high intensity, followed by a rest time of at least one minute. HIIT helps with fat burning and reduces insulin resistance. HIIT forces your body to engage in extra post-exercise oxygen consumption EPOC , also known as afterburn, by creating an oxygen debt to your muscles.

Therefore, even after exercise, your body continues to burn fat. Read more: More Types of exercise to fight PCOS. Changing your lifestyle for the better is essential for managing PCOS.

Two of the most effective methods to do that are through diet and exercise, and both must be addressed for these lifestyle changes to be successful. For women with PCOS, regular exercise has amazing advantages that go far beyond weight loss.

Studies have shown that regular cardio and strength training can help your body respond to insulin more effectively, reducing your risk for diabetes and other issues.

High triglycerides and cholesterol are more common in PCOS-affected women. The metabolic syndrome, which is more common in PCOS-affected individuals, can also be exacerbated by this. When paired with a healthy, low-fat diet, exercise can help lower cholesterol.

Depression symptoms are more likely to appear in PCOS women. Your body releases endorphins during exercise, which are hormones that foster emotions of well-being. You can manage your stress better and lessen some depressive symptoms by doing this. Regular exercise can help you sleep better and fall asleep more quickly.

Sleep apnea, snoring, and even insomnia are more common in women with PCOS. See if regular exercise—just not right before bed—can improve your ability to sleep at night. Your body uses the fat that is already stored in your body as fuel when you burn more calories than you consume.

Of course, doing this aids in weight loss and insulin reduction. In addition, having too much fat affects the way estrogen is produced in your body. Getting rid of some of those additional fat deposits will help regulate your hormones and, ideally, PCOS.

The following advice can be helpful if you're unsure of how to start establishing or changing your fitness regimen:. There is no ideal workout regimen, and each person's exercise program will be slightly different. In the end, we aim to develop a movement regimen that is supportive of PCOS recovery and whole-body health.

This is continuously evaluating the situation and using your body's response to make adjustments. Your PCOS symptoms may be reduced by working with a dietitian to encourage appropriate eating behaviors.

Type 2 diabetes is more frequently diagnosed in PCOS-positive women than in PCOS-negative women. Women with PCOS must consume high-quality, high-fiber carbs, much like those with diabetes.

Your blood sugar levels will be stabilized as a result of this. A balanced PCOS diet will assist in maintaining your body's homeostatic equilibrium.

Bloood K. Hutchison, Nigel K. Stepto, Cheryce L. Harrison, Lisa J. Moran, Boyd J. Strauss, Helena J. Context: Polycystic ovary syndrome PCOS is an insulin-resistant IR state.

0 thoughts on “Effects of exercise on blood sugar in individuals with PCOS”