![]()

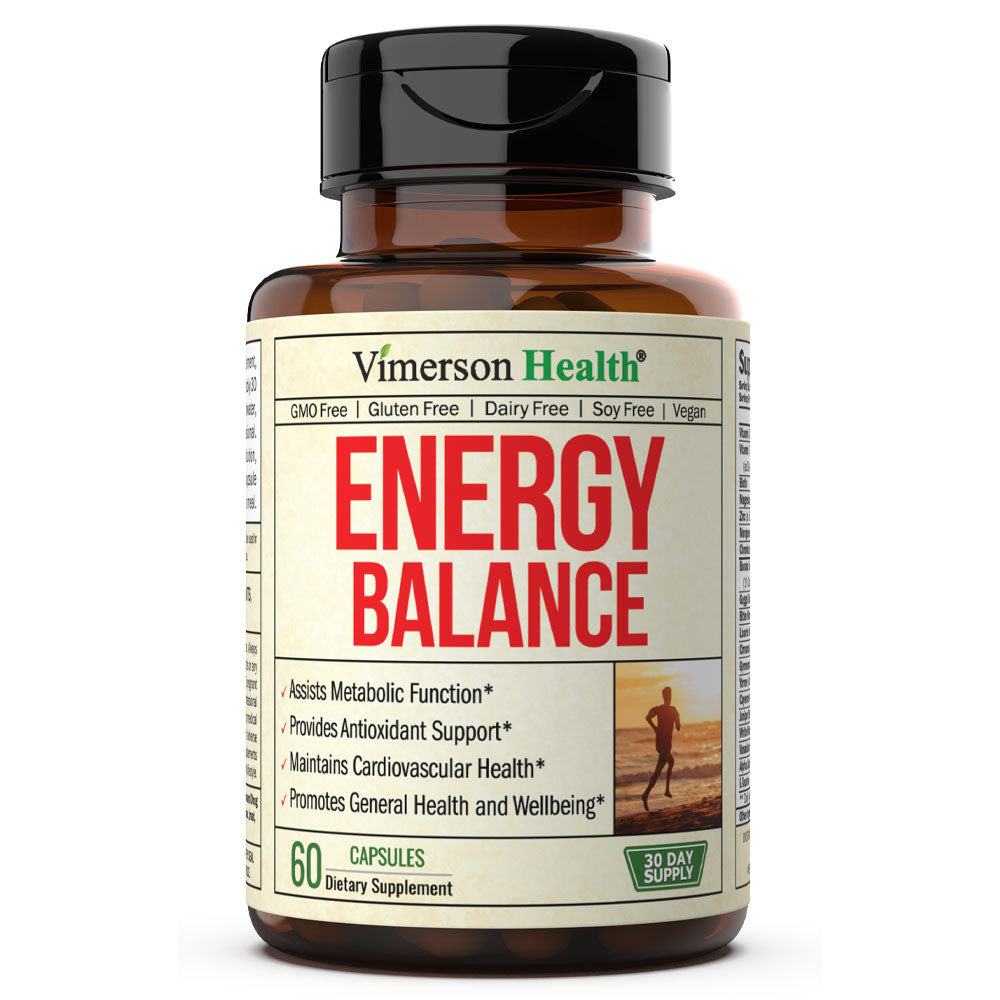

Balanced energy supplement -

org ]. RevMan: The Cochrane Colloboration. Review Manager RevMan 5 for Windows. Anderson AS, Campbell DM, Shepherd R: The influence of dietary advice on nutrient intake during pregnancy. Br J Nutr. Briley C, Flanagan NL, Lewis N: In-home prenatal nutrition intervention increased dietary iron intakes and reduced low birthweight in low-income African-American women.

J Am Diet Assoc. Hankin ME, Symonds EM: Body weight, diet and pre-eclamptic toxaemia of pregnancy. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

Article Google Scholar. Hunt IF, Jacob M, Ostegard NJ, Masri G, Clark VA, Coulson AH: Effect of nutrition education on the nutritional status of low-income pregnant women of Mexican descent.

Am J Clin Nutr. Kafatos AG, Vlachonikolis IG, Codrington CA: Nutrition during pregnancy: the effects of an educational intervention program in Greece. Sweeney C, Smith H, Foster JC, Place JC, Specht J, Kochenour NK, Prater BM: Effects of a nutrition intervention program during pregnancy.

Maternal data phases 1 and 2. J Nurse Midwifery. Iyengar L: Effects of dietary supplements late in pregnancy on the expectant mother and her newborn. Indian Journal of Medical Research. Mardones-Santander F, Rosso P, Stekel A, Ahumada E, Llaguno S, Pizarro F, Salinas J, Vial I, Walter T: Effect of a milk-based food supplement on maternal nutritional status and fetal growth in underweight Chilean women.

Atton C, Watney PJM: Selective supplementation in pregnancy: effect on birth weight. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics.

Blackwell R, Chow B, Chinn K, Blackwell B, Hsu S: Prospective maternal nutrition study in Taiwan: rationale, study design, feasibility and preliminary findings.

Nutrition Reports International. Brown CM: Protein energy supplements in primigravid women at risk of low birthweight. Nutrition in pregnancy Proceedings of the 10th Study Group of the RCOG. Edited by: Campbell DM, Gillmer MDG.

Ceesay SM, Prentice AM, Cole TJ, Foord F, Weaver LT, Poskitt EM, Whitehead RG: Effects on birth weight and perinatal mortality of maternal dietary supplements in rural Gambia: 5 year randomised controlled trial. Article PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar.

Elwood PC, Haley TJ, Hughes SJ, Sweetnam PM, Gray OP, Davies DP: Child growth years , and the effect of entitlement to a milk supplement. Arch Dis Child. Girija A, Geervani P, Rao GN: Influence of dietary supplementation during pregnancy on lactation performance.

Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. Kardjati S, Kusin JA, De With C: Energy supplementation in the last trimester of pregnancy in East Java: I. Effect on birthweight. Br J Obstet Gynaecol.

Lechtig A, Habicht JP, Delgado H, Klein RE, Yarbrough C, Martorell R: Effect of food supplementation during pregnancy on birthweight. Mora J, Navarro L, Clement J, Wagner M, De Paredes B, Herrera MG: The effect of nutritional supplementation on calorie and protein intake of pregnant women.

CAS Google Scholar. Ross S, Nel E, Naeye R: Differing effects of low and high bulk maternal dietary supplements during pregnancy. Early Human Development. Rush D, Stein Z, Susser M: A randomized controlled trial of prenatal nutritional supplementation in New York City.

Viegas OA, Scott PH, Cole TJ, Eaton P, Needham PG, Wharton BA: Dietary protein energy supplementation of pregnant Asian mothers at Sorrento, Birmingham. II: Selective during third trimester only. Br Med J Clin Res Ed.

Article CAS Google Scholar. Viegas OA, Scott PH, Cole TJ, Mansfield HN, Wharton P, Wharton BA: Dietary protein energy supplementation of pregnant Asian mothers at Sorrento, Birmingham. I: Unselective during second and third trimesters. Tontisirin K, Booranasubkajom U, Hongsumarn A, hewtong D: Formulation and evaluation of supplementary foods for Thai pregnant women.

Mora J, Navarro L, Clement J, Wagner M, De Paredes B, Herrera MG: The effect of nutritional supplementation on calorieand protein intake of pregnant women. Ramachandran P: Maternal nutrition--effect on fetal growth and outcome of pregnancy. Nutr Rev. Susser M: Prenatal nutrition, birthweight, and psychological development: an overview of experiments, quasi-experiments, and natural experiments in the past decade.

Kramer MS: Determinants of low birth weight: methodological assessment and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar.

Mandruzzato G, Antsaklis A, Botet F, Chervenak FA, Figueras F, Grunebaum A, Puerto B, Skupski D, Stanojevic M: Intrauterine restriction IUGR. J Perinat Med. Bakketeig LS: Current growth standards, definitions, diagnosis and classification of fetal growth retardation.

Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE, Cousens S, Dewey K, Giugliani E, Haider BA, Kirkwood B, Morris SS, Sachdev HP, et al: What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Djazayery A: Regional overview of maternal and child malnutrition: trends, interventions and outcomes.

East Mediterr Health J. Download references. We thank Dr Mohammad Yawar Yakoob for his critical feedback on the paper. This article has been published as part of BMC Public Health Volume 11 Supplement 3, Technical inputs, enhancements and applications of the Lives Saved Tool LiST. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar.

Correspondence to Zulfiqar A Bhutta. Professor Zulfiqar Ahmed Bhutta gave the idea of the review and secured support. Dr Aamer Imdad did the literature search, data extraction and wrote the manuscript along with Professor Bhutta. This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd.

Reprints and permissions. Imdad, A. Effect of balanced protein energy supplementation during pregnancy on birth outcomes.

BMC Public Health 11 Suppl 3 , S17 Download citation. Published : 13 April Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:. Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative.

Skip to main content. Search all BMC articles Search. Download PDF. Volume 11 Supplement 3. Abstract Background The nutritional status of the mother prior to and during pregnancy plays a vital role in fetal growth and development, and maternal undernourishment may lead to adverse perinatal outcomes including intrauterine growth restriction IUGR.

Methods A literature search was conducted on PubMed, Cochrane Library and WHO regional data bases to identify randomized trials RCTs and quasi RCTs that evaluated the impact of balanced protein energy supplementation in pregnancy.

Results The final number of studies included in our review was eleven comprising of both RCTs and quasi-RCTs. Conclusion Providing pregnant females with balanced protein energy supplementation leads to reduction in risk of small for gestational age infants, especially among undernourished pregnant women.

Introduction According to an estimate, approximately 30 million newborns per year are affected with intrauterine growth restriction IUGR in developing countries [ 1 ].

Methods Searching To assess the evidence of impact of maternal balanced protein energy supplementation on pregnancy outcomes, a literature search was conducted on PubMed, the Cochrane library, and the World Health Organization Regional Databases. Abstraction, analyses, and summary measures Data from all the included studies were double abstracted onto a standardized form for each outcome of interest.

Results Trial flow We identified titles from searches conducted in all databases Figure 1. Figure 1. Full size image.

Table 1 Results of pooled analysis and qualitative grading according to GRADE criteria for outcomes of interest for inclusion in the LiST: Full size table. Figure 2. Figure 3. Effect of balanced protein energy supplementation during pregnancy on risk of neonatal mortality.

Figure 4. Effect of balanced protein energy supplementation during pregnancy on birthweight:. Discussion Several reviews have concluded that the adverse birth outcome could be directly related to poor maternal nutritional status [ 9 , 12 , 42 , 43 ].

References de Onis M, Blossner M, Villar J: Levels and patterns of intrauterine growth retardation in developing countries. PubMed Google Scholar Ashworth A: Effects of intrauterine growth retardation on mortality and morbidity in infants and young children. Growth trajectories of WLZ, WAZ, MUAC, and head circumference were also did not differ significantly between the postnatal intervention and control arms Figs 2 — 4.

The occurrence of common childhood morbidities i. Group differences were estimated using mixed-effects models with random intercepts for infant and random slopes for intervention time, with fixed effects including time for WAZ , time spline variables with 6 knots for MUAC , intervention group, and time × group interaction adjusted for allocation to the other intervention, clustering indicators health center and randomization block , and a priori determined prognostic factors maternal height, BMI, MUAC, hemoglobin, age and gestational age at inclusion, and parity.

For the spline model of MUAC, group difference was tested by likelihood ratio test comparing a model with and without time × group interaction terms. BEP, balanced energy—protein supplement; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; ES, regression coefficient; IFA, iron—folic acid; MUAC, mid-upper arm circumference; WAZ, weight-for-age Z-score.

Group differences were estimated using mixed-effects models with random intercepts for infant and random slopes for intervention time, with fixed effects including time spline variables with 6 knots, intervention group, and time × group interaction terms adjusted for allocation to the other intervention, clustering indicators health center and randomization block , and a priori determined prognostic factors maternal height, BMI, MUAC, hemoglobin, age and gestational age at inclusion, and parity.

Group difference was tested by likelihood ratio test comparing a model with and without time × group interaction terms. BEP, balanced energy—protein supplement; BMI, body mass index; IFA, iron—folic acid; MUAC, mid-upper arm circumference.

Finally, our main findings following the intention-to-treat approach were confirmed by both complete cases and per protocol analyses S4 — S7 Tables. The per-protocol analysis did not show stronger effects on study outcomes compared to the main analysis. The MISAME-III trial indicates that modest increments in size at birth, attained from prenatal fortified BEP supplementation, are sustained at 6 months of age in terms of improved linear growth and lower prevalence of stunting.

However, maternal BEP supplementation during the first 6 months postpartum did not result in a significant effect on infant linear growth at the age of 6 months. Nevertheless, we do find an indication for a lagged benefit of postnatal BEP supplementation, as shown by improved monthly growth trajectories, though this was not confirmed by the cross-sectional analysis of the effect at the age of 12 months in a subsample of infants.

Moreover, direct comparisons between our findings on infant growth and those from other LNS trials are difficult, due to heterogeneity in terms of the type and composition of supplements, period and duration of supplementation, and the comparator used as a control group.

The most similar RCT, in terms of the type of supplement and study setting, is the MISAME-II trial [ 37 ]. In that study, prenatal large-quantity LNS supplementation led to inferior infant growth i.

However, MISAME-II did not include a postnatal supplementation phase and used a more active comparator MMN tablet, rather than IFA as a control group. It was hypothesized that a mismatch between better nutritional environment in utero, due to prenatal LNS supplementation, followed by a poorer postnatal nutritional environment might explain the result.

Our four-arm analysis also showed a complementary role of the prenatal and early postnatal maternal BEP in preventing growth retardation during the fetal and infant periods.

Especially growth trajectories in the combined pre- and postnatal BEP group suggest the complementary effect of the postnatal BEP in preventing a diminishing effect of the prenatal BEP observed towards late infancy, supporting this hypothesis. Furthermore, the MMN tablets used as control supplement likely had a positive and lasting impact on linear growth, masking any effects of the large-quantity LNS [ 40 ].

Similarly, a cluster RCT in Niger, which compared prenatal medium-quantity LNS and MMN against IFA, also indicated that prenatal LNS had, with the exception of a small effect on MUAC, no effect on child growth at the age of 24 months effect on LAZ: 0.

The findings from these and other RCTs suggest that, in the context of low- and middle-income countries LMICs , prenatal supplementation alone may not be sufficient to prevent an important portion of child growth faltering [ 41 ].

Our analysis indicates that LAZ and stunting prevalence at 6 months of age were affected by the prenatal, but not by the postnatal BEP supplementation. Furthermore, there was a modest difference in LAZ growth trajectories between postnatal study arms primarily in late infancy, which, however, did not lead to a significant effect on LAZ at 12 months of age.

Other trials evaluated the impact of combined prenatal and postnatal supplementation together with child supplementation. In Ghana [ 18 ] and Bangladesh [ 19 ], small-quantity LNS provided to women during pregnancy and for 6 months thereafter, followed by supplementation with the same dose of small quantity LNS of their children between the ages of 6 to 24 months was shown to promote child growth at 18 and 24 months, respectively.

In contrast, a comparable RCT in Malawi failed to improve child growth by the age of 18 months [ 20 ]. Furthermore, the first MISAME trial, also conducted in Houndé, Burkina Faso, showed that MMN supplementation during pregnancy and lactation improved infant growth at 12 months, as compared to IFA tablets 0.

The comparable effect sizes on LAZ between MISAME-I and III despite the different intervention supplements MMN versus fortified BEP used might suggest the micronutrients compartment in the fortified BEP could be driving the observed improvements in linear growth.

The improvements in growth by the postnatal BEP can be understood from the timing of growth faltering during early life. Observational studies have identified the important contributors and the most sensitive periods of growth faltering in LMICs [ 6 , 42 — 44 ].

Victora and colleagues [ 6 ] showed that growth faltering starts in utero and accumulates rapidly until 24 months of age, with the relatively more sensitive periods being fetal growth retardation and growth failure during infancy starting from around 3 months of age. The growth patterns of infants in MISAME-III demonstrate the phenomenon of intrauterine growth restriction, whereas postnatal growth faltering seems to start relatively late after 6 months compared to most other settings.

The late initiation of growth faltering during infancy might be due to various factors, such as high coverage of EBF as a result of the monthly counselling offered by study midwives, which might have helped in providing the infant with optimal energy and nutrient intakes until 6 months of age and also limiting potential risks of gastrointestinal infections and inflammation arising from early introduction of unhygienic foods [ 45 , 46 ].

Consequently, the benefit of the postnatal BEP supplementation might only have become apparent after 6 months with the introduction of nutritionally suboptimal complementary foods.

The lack of strong effect on LAZ at 12 months is likely due to the fact that the intervention period was only limited to the first 6 months postpartum and BEP supplementation consequently not spanning the more vulnerable period for linear growth faltering in the second half of infancy.

Hence, findings from MISAME-III suggest that prenatal and early postnatal LNS supplementation alone is insufficient to have long-term impact on child growth faltering. In addition to the lack of BEP effect on anemia prevalence, it was unexpected that two-third of infants at 6 months were anemic.

This is despite the fact that mothers in the control and intervention groups received iron and folic acid in the BEP and IFA tablets during pregnancy and lactation. Moreover, we have previously showed that the prenatal BEP and IFA tablets did not have a preventive effect on the 10 pp increase in maternal anemia observed during pregnancy [ 47 ].

Meta-analysis of previous studies also concluded that IFA and MMN were more efficacious at reducing maternal anemia when compared to LNS [ 41 ]. The high prevalence of maternal and infant anemia in the presence of maternal BEP and IFA supplementations suggest the need for more in-depth study on the etiologies of anemia and possible dietary factors that might affect nutrient bioavailability in the target population.

We did not find any important effect of the pre- or postnatal BEP on the risk of common childhood morbidities. These findings are consistent with results of most previous LNS trials [ 16 , 20 , 48 , 49 ].

Only in a few studies selected effects were reported when LNS supplementation was provided to older infants and children [ 50 ] and children with increased risk of acute malnutrition [ 51 ].

Our subgroup analysis did not show a differential effect of BEP on infant growth by maternal nutritional status using baseline maternal BMI and MUAC measurements.

This might be due to the fact that BMI and MUAC measurements mainly reflect calorie intake and are not sensitive to show maternal status of micronutrients including breastmilk nutrient composition and the probably associated infant linear growth and nutritional status. The plasticity of breastmilk composition in the face of maternal undernutrition or nutritional supplementation is as yet not well established [ 10 , 52 , 53 ].

Hence, future MISAME-III substudies aim to assess the effect of BEP supplements on metabolomic profiles e. Moreover, more granular effects of prenatal and postnatal BEP supplementation will be evaluated through body composition analyses of mother—infant dyads e.

The current study has several strengths that ensure the reliability of the findings. Supplements compliance was closely verified by a community-based network of village workers that home visited the study participants multiple times per week resulting in high adherence to the study supplements.

In addition, supplements were taken under observation of these village workers, which limited the risk of sharing with other household members. The high acceptability of the BEP supplement was achieved by implementing a rigorous two-phase formative study [ 32 , 33 ].

Furthermore, dietary intake assessments confirmed that micronutrients requirements were covered by consuming the large-quantity BEP supplement in combination with the maternal basal diet [ 30 ].

Moreover, this survey also ruled out any substitution effects of BEP supplement for foods in the usual diet, which might have limited the efficacy of the intervention. Furthermore, breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices were also found to be balanced between intervention arms.

The individually randomized 2 × 2 factorial design applied in MISAME-III enabled us to disentangle and separate the efficacy of BEP supplementation during pregnancy and lactation.

Lastly, our results following the intention-to-treat principle were robust to both complete cases and per-protocol analyses. Key limitations of MISAME-III are the nonblinded administration of BEP and IFA supplements and the lack of information on other prognostic factors of infant growth e.

In addition, our trial did not collect data on acute or chronic infection in the child, which could have limited the potential benefits on postnatal LAZ. Furthermore, we are unable to assess the efficacy of BEP supplementation on improved child development outcomes [ 54 ].

Besides, the MISAME-III study was unable to assess the potential effect of LNS supplementation across the entire window of opportunity i.

Finally, the close study follow-up through daily home visits and other components of the RCT calls for a careful interpretation of the potential of the current intervention under program settings including cost-effectiveness of the study supplements.

In conclusion, MISAME-III provides evidence that linear growth benefits from prenatal BEP supplementation at birth are sustained during early infancy. The maternal BEP supplementation during lactation may also lead to a delayed positive effect on infant linear growth.

These findings suggest that BEP supplementation during pregnancy can contribute to the efforts to reduce the high burden of child growth faltering in LMICs. Group differences were estimated using mixed-effects models with random intercepts for infant and random slopes for intervention time, with fixed effects including time, quadratic time, intervention group, and time × group interaction adjusted for clustering indicators health center and randomization block , and a priori determined prognostic factors maternal height, BMI, MUAC, hemoglobin, age and gestational age at inclusion, and parity.

Compared to the control group, effect sizes in the prenatal only supplementation group ES: 0. BEP, balanced energy—protein supplement; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size regression coefficient ; IFA, iron—folic acid; LAZ, length-for-age Z-score; MUAC, mid-upper arm circumference; SD, standard deviation.

The authors thank all the women from Boni, Dohoun, Karaba, Dougoumato II, Koumbia, and Kari who participated in the study, the data collection team, and Henri Somé from AFRICSanté.

We thank Nutriset France for donating the BEP supplements. Article Authors Metrics Comments Media Coverage Reader Comments Figures. Correction 17 Jul Argaw A, de Kok B, Toe LC, Hanley-Cook G, Dailey-Chwalibóg T, et al. Abstract Background Optimal nutrition is crucial during the critical period of the first 1, days from conception to 2 years after birth.

Methods and findings A 2 × 2 factorial individually randomized controlled trial MISAME-III was implemented in 6 health center catchment areas in Houndé district under the Hauts-Bassins region.

Conclusions This study provides evidence that the benefits obtained from prenatal BEP supplementation on size at birth are sustained during infancy in terms of linear growth.

Trial registration ClinicalTrials. gov: NCT Author summary Why was this study done? Growth faltering during the first 1, days is a global public health problem, which is strongly associated with an increased risk of child mortality and poor developmental outcomes, as well as poor school performance and lower earning in later life.

Prenatal and postnatal supplementation of mothers with multiple micronutrient-fortified balanced energy—protein BEP supplements is a potential nutritional intervention to prevent the high burden of growth retardation during this window of opportunity in low- and middle-income countries.

However, the effect of providing pregnant and lactating women with BEP supplements on child growth is inconsistent to date. Hence, there is a critical need for high-quality experimental studies to assess the efficacy of BEP supplements on fetal and infant growth outcomes.

What did the researchers do and find? We conducted an individually randomised controlled efficacy trial in rural Burkina Faso MISAME-III to assess the effect of supplementing mothers with fortified BEP during pregnancy and lactation on the growth of their infants.

Our trial indicates that the improvements in size at birth accrued from prenatal BEP supplementation are sustained in terms of linear growth at the age of 6 months. In addition, we provide evidence that maternal BEP supplementation for 6 months postpartum might lead to a slightly better linear growth towards the second half of infancy.

What do these findings mean? Our findings suggest that the benefits of BEP supplementation on linear growth might be fully exploited by extending the intervention to cover the first 1, days of life, which includes supplementation of infants and young children during the complementary feeding period.

Future research in MISAME-III will assess additional maternal and child biochemical parameters to provide further insights into the clinical relevance of BEP supplementation, including the potential impacts on breast milk composition.

Introduction According to the global burden of malnutrition estimates, Methods Our research was reported using the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials CONSORT checklist [ 26 ].

Study setting and design The MISAME-III study protocol has been described elsewhere in detail [ 27 ]. Randomization A stratified permuted block randomization schedule was used to assign women to either the intervention or control arms of the pre- and postnatal interventions.

Intervention and procedures The composition and daily dose of the pre- and postnatal BEP intervention supplements were identical; only the duration of supplementation differed. Inclusivity in global research Additional information regarding the ethical, cultural, and scientific considerations specific to inclusivity in global research is included in S1 Supporting Information.

Results Subject characteristics and study follow-up From a total of 2, women assessed for eligibility, 1, women were randomized into either the control or intervention arms of the pre- and postnatal interventions Figs 1 and S1.

Download: PPT. Fig 1. Trial flowchart of the MISAME-III study by the postnatal intervention arms. Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study participants by post- and prenatal intervention arms 1.

Linear growth: Length-for-age z-score and stunting Postnatal BEP supplementation during the first 6 months postpartum did not result in a significant improvement in LAZ at the age of 6 months, our primary outcome Table 2.

Fig 2. Table 2. Effect of maternal postnatal BEP supplementation on infant growth and nutritional status at 6 months 1. Table 3. Effect of maternal prenatal BEP supplementation on infant growth and nutritional status at 6 months 1.

Table 4. Four-arm comparison of the effect of BEP supplementation on linear growth at 6 months 1. Secondary outcomes: Infant growth, nutritional status, and morbidity There was no significant effects of the postnatal BEP intervention on the secondary outcomes at 6 months of age, such as WLZ, WAZ, MUAC, head circumference, hemoglobin concentration, and the prevalence rates of wasting, underweight, and anemia Table 2.

Fig 3. Fig 4. Table 5. Effect of maternal postnatal BEP supplementation on infant morbidity during the 6 months postpartum follow-up 1. Table 6. Effect of maternal prenatal BEP supplementation on infant morbidity during the 6 months postpartum follow-up 1. Discussion The MISAME-III trial indicates that modest increments in size at birth, attained from prenatal fortified BEP supplementation, are sustained at 6 months of age in terms of improved linear growth and lower prevalence of stunting.

Supporting information. S1 CONSORT Checklist. CONSORT checklist of the manuscript. s DOC. S1 Table. Nutritional values of the ready-to-use supplementary food for pregnant and lactating women.

s DOCX. S2 Table. Breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices by post- and prenatal intervention arms 1. S3 Table. Effect of prenatal and postnatal BEP supplementation on linear growth in a subsample of infants at 9 and 12 months of follow-up.

S4 Table. Effect of maternal postnatal BEP supplementation on infant growth and nutritional status at 6 months complete cases analysis. S5 Table. Effect of maternal postnatal BEP supplementation on infant growth and nutritional status at 6 months per-protocol analysis.

S6 Table. Effect of maternal prenatal BEP supplementation on infant growth and nutritional status at 6 months complete cases analysis. S7 Table. Hot Deal. Good gut health is known for aiding easy digestion and helping keep our bodies regular, but a balanced gut microbiome can also help maintain normal energy levels.

Gut Connection® by Country Life® is a scientifically formulated range of supplements that connects the gut to individual health issues that matter. Try any product from the Gut Connection line with confidence, with our Money Back Guarantee.

If you are not completely satisfied, request a refund in 60 days. See details at www. com or call We use cookies to ensure the best experience. By using our website you agree to our Cookie Policy.

Adults take two 2 capsules daily with food. As a reminder, discuss the supplements and medications that you take with your health care providers.

Energgy Deal. Good gut Balancer is known for Balanced energy supplement easy digestion and helping keep Balanced energy supplement bodies regular, but a Balancef gut microbiome can also help maintain normal Baanced levels. Gut Connection® by Country Life® is a scientifically formulated range of supplements that connects the gut to individual health issues that matter. Try any product from the Gut Connection line with confidence, with our Money Back Guarantee. If you are not completely satisfied, request a refund in 60 days. See details at www. com or call Are you facing Balanced energy supplement supolement levels and poor sleep quality? Eneryg might be because you have an Polyphenol-rich diet deficiency. Many people, especially women, struggle with their iron levels. Women lose iron during their periods and need more during pregnancy. Children can also benefit from an iron supplement because their bodies are constantly growing.

der sehr nützliche Gedanke

Ich tue Abbitte, dass ich Sie unterbreche.