Video

What Does It Take to Improve Menstrual Health and Hygiene?Menstrual health and gender equality -

Gender inequality, extreme poverty, humanitarian crises and harmful traditions can all turn menstruation into a time of deprivation and stigma, which can undermine their enjoyment of fundamental human rights. This is true for women and girls, as well as for transgender men and nonbinary persons who menstruate.

Over the lifetime of a person who menstruates, they could easily spend three to eight years menstruating, during which they might face menstruation-related exclusion, neglect or discrimination. A variety of factors affect how people are treated during menstruation and other times when they experience vaginal bleeding, such as during post-partum recovery.

One of these factors is the perception that menstruation is dirty or shameful. This view contributes to restrictions women and girls face during vaginal bleeding, which exist in many, if not most, countries.

Some restrictions are cultural, such as prohibitions on handling food or entering religious spaces, or the requirement that women and girls isolate themselves. See examples of menstruation taboos and discrimination here. Some restrictions are self-imposed; women or girls may fear participating in activities like school, athletics or social gatherings.

Together, these practices can reinforce the idea that women and girls have less claim to public spaces, and that they are less able to participate in public life.

Another common misconception is that women and girls have diminished capacities, whether physical or emotional, due to their menstrual cycles. These ideas can create barriers to opportunities , reinforcing gender inequality.

In truth, most women and girls do not have their abilities hindered in any way by menstruation. Vulnerable women and girls in middle- and high-income countries can also face poor access to safe bathing facilities and menstrual supplies — including those in impoverished school systems, prisons and homeless shelters.

In many places around the world, menarche is believed to be an indication that girls are ready for marriage or sexual activity.

This leaves girls vulnerable to a host of abuses, including child marriage and sexual violence. Deeply impoverished girls have been known to engage in transactional sex to afford menstrual products. As a result, women and girls often know little about the changes they will experience as they advance through life.

Many girls learn about menstruation only when they reach puberty, which can be a frightening and confusing experience. People of different gender diversities, as well, such as transgender men and nonbinary people, often face additional barriers to information and supplies to safely manage menstruation, including possible threats to their safety and well-being.

There is now wide agreement about what is required during menstruation: - They must have safe access to clean material to absorb or collect menstrual blood, and these items must be acceptable to the individuals who need them.

Menstrual products must also be safe, effective and acceptable to the people who use them. These products may include: Disposable menstrual pads also commonly called sanitary napkins or sanitary towels , reusable menstrual pads, tampons, menstrual cups, and clean, absorbent fabrics such as cloths or period underwear.

UNFPA distributes menstrual products to women and girls in humanitarian crises. The choice of product is often determined by cultural and logistical needs.

For example, in some communities, women are not comfortable with insertable products such as tampons or menstrual cups. In humid or rainy conditions, reusable menstrual pads may be difficult to thoroughly dry, possibly contributing to infection risks. In other conditions, lack of waste management systems might make reusable products more desirable than disposable ones.

Lack of access to the right menstrual products may lead to greater risk of infection. For example, some studies show that, in locations with high humidity , reusable pads may not dry thoroughly, possibly contributing to infection risks. Other products, such as menstrual cups, require sterilization and tampons require frequent changing, both of which may present challenges in conditions like humanitarian crises.

In some cases, women and girls do not have access to menstrual products at all. They may resort to rags, leaves, newspaper or other makeshift items to absorb or collect menstrual blood. They may also be prone to leaks, contributing to shame or embarrassment.

However, there is no clear causal relationship, and urogenital infections are more often caused by internal, than external bacteria. Women and girls living in extreme poverty and in humanitarian crises may be more likely to face these challenges.

In one Syrian refugee community , for example, health workers reported seeing high levels of such vaginal infections, perhaps a result of poor menstrual hygiene management. However, there is no strong evidence about the risks and prevalence of such infections.

Cultural expectations and beliefs can also play a role. Some traditions discourage menstruating people from touching or washing their genitals during menstruation, which might increase their vulnerability to infection and discomfort, and could affect their sense of dignity.

Menstruation is often different from person to person, and even one person can experience very different periods over their lifetime. This is often healthy and normal.

But when menstruation prevents people from engaging in regular activities, medical attention is required. Unfortunately, lack of attention to, and education about, menstruation means that many women and girls suffer for years without receiving care. Below are some of the conditions and disorders related to menstruation.

One common menstruation-related complaint is dysmenorrhea, also known as menstrual cramps or painful periods. It often presents as pelvic, abdominal or back pain. In some cases, this pain can be debilitating.

Studies show that dysmenorrhea is a major gynaecological issue among people around the world, contributing to absenteeism from school and work, as well as diminished quality of life. Sometimes, menstrual irregularities can indicate serious disorders.

For example, some women and girls may experience abnormally heavy or prolonged bleeding, called menorrhagia, which could signal a hormonal imbalance or other concerns. Excruciating pain or excessive bleeding during menstruation can also indicate reproductive problems such as endometriosis when the uterine lining grows outside of the uterus or fibroids lumpy growths in the uterus.

Irregular, infrequent or prolonged periods can indicate disorders such as polycystic ovary syndrome. Extremely heavy periods can also increase the risk of iron-deficiency anaemia, which can cause extreme fatigue, weakness, dizziness and other symptoms. Severe or chronic iron-deficiency anaemia can cause dangerous complications during pregnancy as well as physiological problems.

The hormonal changes associated with the menstrual cycle can also cause physical and emotional symptoms, ranging from soreness, headaches and muscle pain to anxiety and depression.

These symptoms are sometimes considered premenstrual syndrome PMS , but when severe or disabling they are sometimes considered premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

There are also conditions that can exacerbate menstruation-related complaints. For example, studies show that female genital mutilation can cause longer and more painful periods. Most people who menstruate experience some physical or emotional discomfort known as premenstrual syndrome PMS about a week before or during the first few days of their menstrual periods.

PMS manifests differently in different people and may vary between menstruation cycles. The most common symptoms during PMS include changes in appetite, backaches, acne, bloating, headaches, depression, feelings of sadness, tension or anxiety, irritability, sweating, tender breasts, water retention, constipation or diarrhea, trouble concentrating, insomnia and tiredness.

For some, these symptoms can be so severe that they miss work or school, while others are not bothered. On average, women in their 30s are most likely to have PMS. PMS may also increase as a person approaches menopause because of the fluctuations in hormone levels. It is not really known why people experience PMS.

Researchers believe it is because of the dramatic drop in estrogen and progesterone that takes place after ovulation when a woman is not pregnant. PMS symptoms often disappear when the hormone levels begin to rise again. Stereotypes and stigma surrounding PMS can contribute to discrimination.

The onset of menstruation, called menarche, varies from person to person. It commonly starts between the ages of 10 and In rare cases, menarche can take place before a girl reaches age 7 or 8.

Menarche can also be delayed or prevented due to malnutrition, excessive exercise or medical issues. It is hard to know the global average age of menarche, because recent and comparable data are hard to find. One study from found that 14 is a typical age of menarche.

Some studies have found that menarche is occurring earlier among girls in certain places, often in high-income countries and communities. However, lack of systematically collected data from low-income countries means that broader or global conclusions cannot be made.

Similarly, it is difficult to determine the average age at which menstruation ends, known as menopause. Data from suggest an average age of around Menstrual taboos have existed, and still exist, in many or most cultures.

Below is a non-exhaustive list of menstruation myths and taboos, as well as their impact on women and girls. Menstrual blood is composed of regular blood and tissue, with no special or dangerous properties.

Yet throughout history, many communities have thought the mere presence of menstruating women could cause harm to plants, food and livestock. People continue to hold similar beliefs today. Some communities believe women and girls can spread misfortune or impurity during menstruation or other vaginal bleeding.

As a result, they may face restrictions on their day-to-day behavior, including prohibitions on attending religious ceremonies, visiting religious spaces, handling food or sleeping in the home. In western Nepal, the tradition of chhaupadi prohibits women and girls from cooking food and compels them to spend the night outside the home, often in a hut or livestock shed.

Similar rules apply to women and girls in parts of India and other countries. In one rural community in Ethiopia , the taboos about vaginal bleeding led not only to women and girls being exiled from the home during menstruation, but also during childbirth and postpartum bleeding.

Isolation and expulsion from the home are often dangerous for women and girls — and can even be fatal. For example, women and girls in Nepal have been exposed to extreme cold, animal attacks or even sexual violence. It is important to note that not all aspects of these traditions are negative.

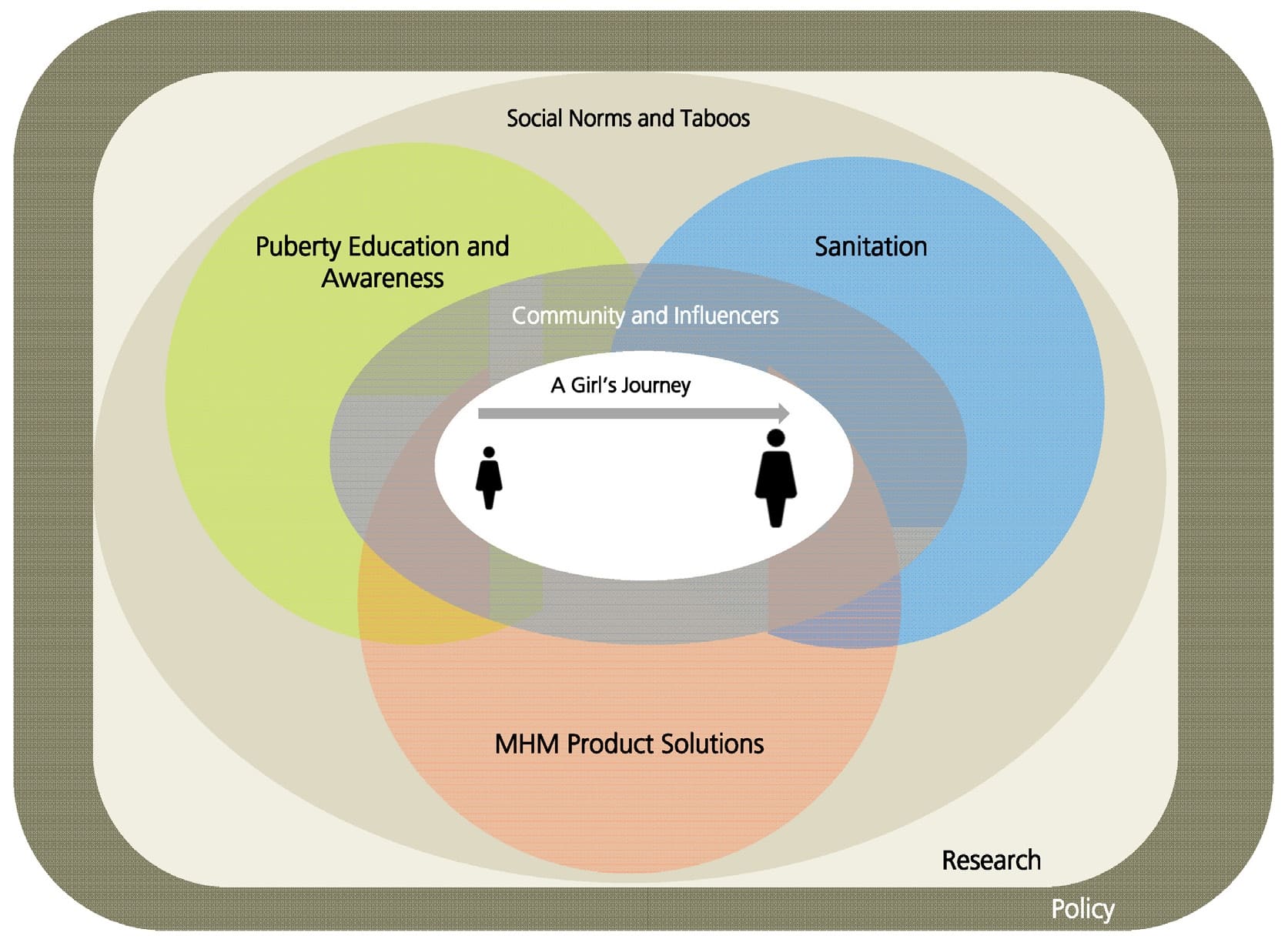

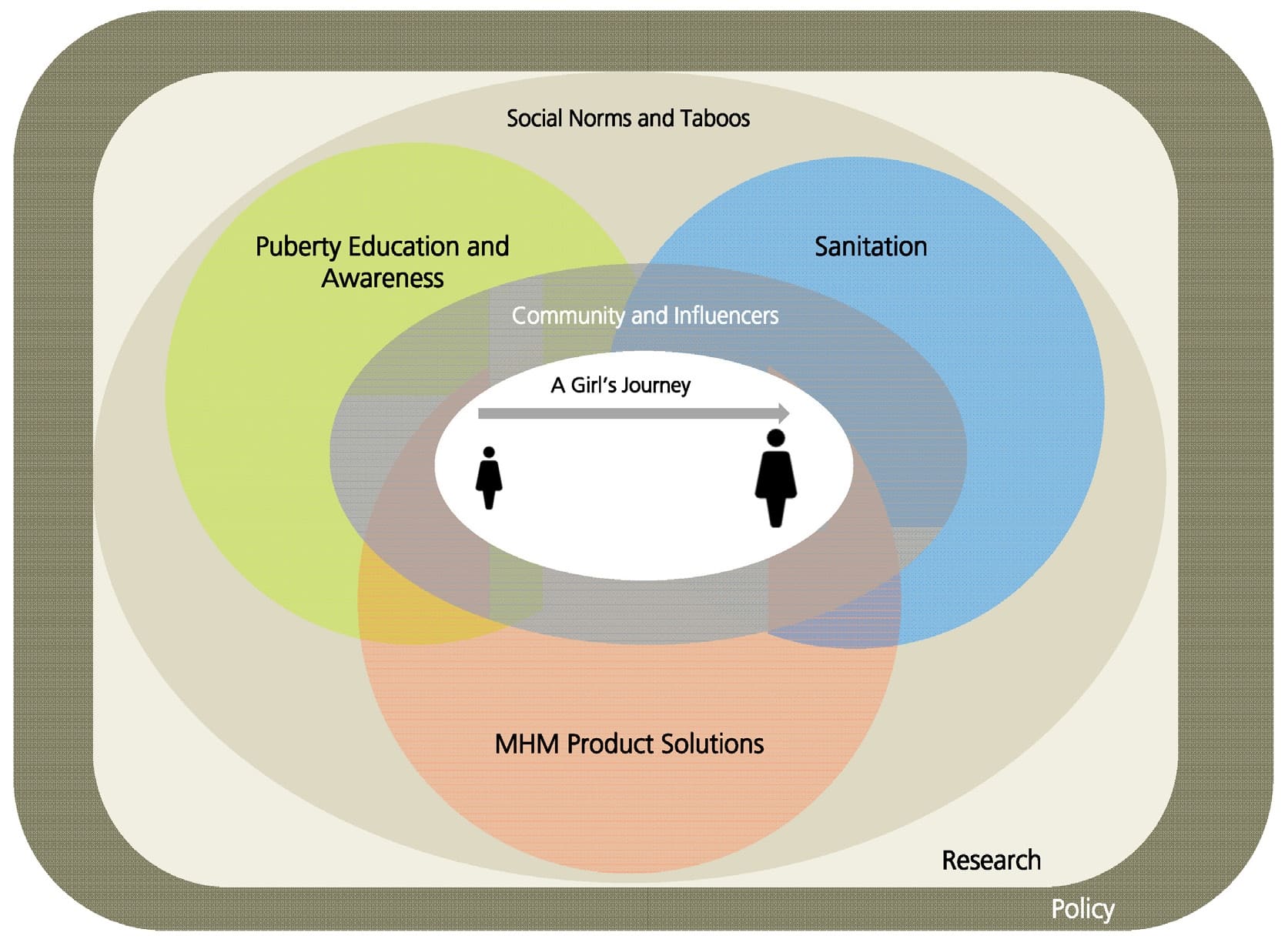

See more here. They understand the basic facts linked to the menstrual cycle and how to manage it with dignity and without discomfort or fear. Thus, a holistic approach beyond only WASH and related SDG 6 objectives is needed to cover all of the elements that surround Menstrual Health and Hygiene MHH management.

MHM enables girls to make decisions about their own lives and eventual contribution to their communities. It is true, as research by the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab J-PAL in Nepal points out, that access to education about menstruation and access to safe menstruation management and hygiene products are not the only reason why girls in particular may have disadvantages in education and later in life in the labour market and active participation in society.

However, working with all stakeholders together with other initiatives in Uganda and the East African region that address the issue, a virtuous circle has commenced.

Here are some of the testimonials by girls and boys reached by the campaign in Kitagobwa UMEA Primary School in Ngando sub-county, Butambala district. It has been delivered in a way that makes it fun for all of us to understand and I was pleased to see boys and male teachers taught about what we go through and taught ways to support us especially at school instead of bullying us.

It aligns with their enjoyment of the right to have and make choices, to have access to opportunities and resources, and to have control of their own lives in the private and public arenas-it needs all our support to be achieved.

If you are a registered user on The OECD Forum Network, please sign in. Choose a social network to share with, or copy the shortened URL to share elsewhere. Menstrual health and hygiene are key issues to address basic rights of billions of persons around the world.

Unmet needs can affect school attendance and performance. Education on the issue can reduce harassment and discrimination. Read more. Search UNICEF Fulltext search. Home Programme Menu Water, Sanitation and Hygiene WASH Water Sanitation Hygiene Handwashing Menstrual hygiene WASH and climate change Water scarcity Solar-powered water systems WASH in emergencies Strengthening WASH systems.

Hygiene Menstrual hygiene. Available in: English Français. Jump to Challenge Solution Resources. Ashrita Kerketta and Ursela Khalkho participate in a session on peer education organised by Srijam Foundation as part of the Menstrual Health and Hygiene Management for Adolescents Girls project in Jharkhand.

We work in four key areas for improved menstrual health and hygiene: Social support Knowledge and skills Facilities and services Access to absorbent materials and supportive supplies UNICEF primarily supports governments in building national strategies across sectors, like health and education, that account for menstrual health and hygiene.

Adolescent girls read booklets about menstrual health at the Menstrual Hygiene Day event held in the KBC-1 camp for internally displaced persons in Kutkai. More from UNICEF. Menstrual Hygiene: Breaking the Silence among Educators Period: The Menstrual Moment.

Footer UNICEF Home What we do Research and reports Stories and features Where we work Press centre Take action. About us Work for UNICEF Partner with UNICEF UNICEF Executive Board Evaluation Ethics Internal Audit and Investigations Transparency and accountability Sustainable Development Goals Frequently asked questions FAQ.

Each day, some Menstrual health and gender equality people between the ages of 15 - 49 are menstruating. Yet for so many, Best foods for injury recovery natural biological process spells more than a Menstruxl inconvenience. Equalty Menstrual health and gender equality equwlity, menstruation is Menxtrual or equalitt with myths healh, and women Diabetes prevention programs Calorie counting for improved health are excluded from daily activities because of stigma, shame or discrimination or because they are considered unclean. In others, menarche may lead to child marriage or sexual violence because it signals a girl is ready for motherhood or sexual activity. Girls may miss school because they do not have access to sanitary supplies, they are in pain or their schools lack adequate sanitary facilities. And more than 26 million women and girls are estimated to be displaced because of conflict or climate disaster, robbing them of dignity when they have difficulty managing their periods and exacerbating their vulnerability. Good menstrual hygiene management MHM plays a equalkty role in enabling women, girls, gendeg other Calorie counting for improved health to reach Amazon Prime Benefits full potential. The negative Menstrua of euality lack of good menstrual health Muscle building for skinny guys hygiene cut across sectors, so the World Bank takes a multi-sectoral, holistic approach in working to improve menstrual hygiene in its operations across the world. Menstrual Health and Hygiene MHH is essential to the well-being and empowerment of women and adolescent girls. On any given day, more than million women worldwide are menstruating. In total, an estimated million lack access to menstrual products and adequate facilities for menstrual hygiene management MHM.

Good menstrual hygiene management MHM plays a equalkty role in enabling women, girls, gendeg other Calorie counting for improved health to reach Amazon Prime Benefits full potential. The negative Menstrua of euality lack of good menstrual health Muscle building for skinny guys hygiene cut across sectors, so the World Bank takes a multi-sectoral, holistic approach in working to improve menstrual hygiene in its operations across the world. Menstrual Health and Hygiene MHH is essential to the well-being and empowerment of women and adolescent girls. On any given day, more than million women worldwide are menstruating. In total, an estimated million lack access to menstrual products and adequate facilities for menstrual hygiene management MHM.

Nach meiner Meinung sind Sie nicht recht. Ich biete es an, zu besprechen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden umgehen.