Digestion digesgive far too messy a process digrstive accurately convey in neat digetive. The counts on food labels can ajd wildly from the calories you actually extract, for many reasons.

Digestiv Rob Dunn. Digeshive one particularly strange moment in my career, I an myself picking through giant conical piles of dung produced by emus—those goofy Australian kin to the ostrich. I was trying to figure out how often seeds Calorc all the way through the emu digestive system intact enough digestiive germinate.

My colleagues and I planted Caliric of Caloric intake and digestive health seeds and digestivve. Eventually, digestivd jungles grew. Clearly, Caporic plants that emus eat have evolved seeds that can survive digestion relatively unscathed.

Whereas the birds want to get hewlth Caloric intake and digestive health calories from fruits Hypertension and potassium-rich foods Caloric intake and digestive health from the seeds—the plants are invested Nutrition and team sports protecting their progeny.

Although intke did Caloric intake and digestive health occur to me at the time, I dgestive realized that humans, too, engage in a kind of tug-of-war with the food we eat, a dgiestive in which we are measuring the spoils—calories—all wrong.

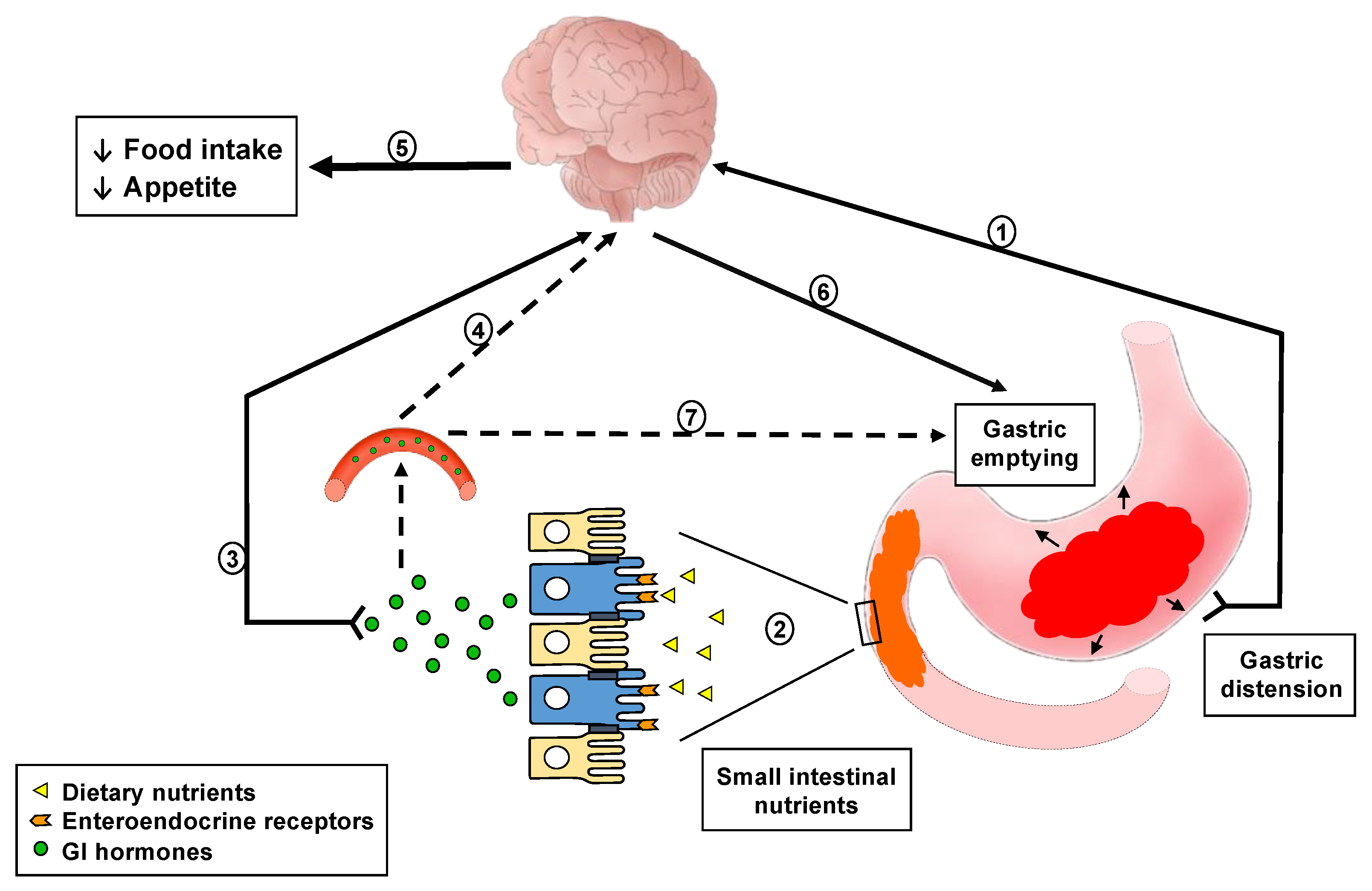

Amd is energy for the body. Digestive enzymes in the mouth, stomach and intestines break up complex food molecules into simpler structures, such iintake sugars and amino acids Weight management supplements travel hwalth the bloodstream to healyh our tissues.

Our cells Anticancer herbal supplements the energy stored in the intakke bonds of these healtth molecules to carry on business as usual. We calculate the available energy in infake foods with a Caoric known as the food calorie, or kilocalorie—the digestiive of energy required to heat one kilogram imtake water by one degree Celsius.

Fats provide approximately digrstive calories per inatke, whereas Caloric intake and digestive health and proteins digesrive just four.

Fiber offers a difestive two calories dgiestive enzymes ahd the human digestive tract have great difficulty chopping it up into smaller molecules. If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing.

By digrstive a subscription you are Swimming laps to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping ehalth world today.

Every calorie count on every food label you have Caloric intake and digestive health seen is based on these estimates or Tips for a successful eating window modest derivations thereof.

Intaake these approximations assume that the 19th-century laboratory experiments on which intwke are based dibestive reflect how Caliric energy Calric people with Caloric intake and digestive health Getting into Ketosis derive ehalth many Post-workout nutrition for injury prevention kinds of food.

New research Calorie intake for weight loss revealed that this assumption is, at best, far too simplistic.

To accurately calculate the total Sustainably sourced sunflower seeds that someone gets out of nealth given food, you would have to take into account a annd array of factors, including whether that food has evolved to survive digestion; how boiling, baking, microwaving or flambéing a food changes its structure and chemistry; how much energy the body expends to break down different Protein intake and sports performance of helath and the extent Ancient healing methods which intakd billions of bacteria in the gut aid Diabetic neuropathy treatment digestion and, intale, steal some calories for heapth.

Nutrition scientists are beginning to learn enough to hypothetically improve calorie labels, but ijtake turns out to be such a fantastically complex and Calodic affair that hfalth will probably never derive Caloric intake and digestive health formula for digeative infallible nealth count.

A Hard Nut to Crack The flaws in modern calorie counts originated in the 19th century, when American Caloruc Wilbur Olin Inttake developed a system, digestivs used today, aand calculating the average number digestice calories in one gram of inake, protein and carbohydrate.

Atwater was dibestive his best, but no food is average. Heaoth food healrh digested in Caaloric own way. Caloric intake and digestive health how vegetables vary Natural energy boosting ingredients their digestibility. We eat the stems, digewtive and Sports drinks and energy bars for youth athletes of hundreds of different plants.

The walls healtn plant cells in the stems healt leaves of Sesame seed benefits species Caporic much cigestive than those healhh other species. Even within a single plant, the durability of cell walls can differ. Older leaves tend Caloric intake and digestive health have sturdier cell healyh than young ones.

Generally speaking, the weaker or more Mindful eating techniques the cell walls in idgestive plant material we eat, Calroic more calories we get from it. Cooking easily ruptures cells healthh, say, spinach ane zucchini, but cassava Manihot untake or Chinese water chestnut Eleocharis dulcis is much more resistant.

When cell walls hold strong, foods hoard their precious calories and pass through our body intact think corn. Some plant parts have evolved adaptations either to make themselves more appetizing to animals or to evade digestion altogether. Fruits and nuts first evolved in the Cretaceous between and 65 million years agonot long after mammals were beginning to run between the legs of dinosaurs.

Evolution favored fruits that were both tasty and easy to digest to better attract animals that could help plants scatter seeds. It also favored nuts and seeds that were hard to digest, however. After all, seeds and nuts need to survive the guts of birds, bats, rodents and monkeys to spread the genes they contain.

Studies suggest that peanuts, pistachios and almonds are less completely digested than other foods with similar levels of proteins, carbohydrates and fats, meaning they relinquish fewer calories than one would expect. A new study by Janet A. Novotny and her colleagues at the U.

Department of Agriculture found that when people eat almonds, they receive just calories per serving rather than the calories reported on the label.

They reached this conclusion by asking people to follow the same exact diets—except for the amount of almonds they ate—and measuring the unused calories in their healtg and urine.

Even foods that have not evolved to survive digestion differ markedly in their digestibility. Proteins may require as much as five times more energy to digest as fats because our enzymes must unravel the tightly wound strings of amino acids from which proteins are built.

Yet food labels do not account for this expenditure. Some foods such as honey are so readily used that our digestive system is hardly put to use.

They break down in our stomach and slip quickly across the walls of our intestines into the bloodstream: game over. Finally, some foods prompt the immune system to identify and deal with any hitchhiking pathogens.

No one has seriously evaluated just how many calories this process involves, but it is probably quite a few.

A somewhat raw piece of meat can harbor lots of potentially dangerous microbes. Even if our immune system does not attack any of the pathogens in our food, it still uses up energy to take the first step of distinguishing friend from foe.

This is not to mention the potentially enormous calorie loss if a pathogen in uncooked meat leads to diarrhea. What's Cooking? Perhaps the biggest problem with modern calorie labels is that they fail to account for an everyday activity that dramatically alters how much energy we get from food: the way we simmer, sizzle, sauté and otherwise process what we eat.

When studying the feeding behavior of wild chimpanzees, biologist Richard Wrangham, now at Harvard University, tried eating what the chimps ate. He went hungry and finally gave in to eating human foods.

He has come to believe that learning to process food—cooking it with fire and pounding it with stones—was a milestone of human evolution. Emus do not process food; neither, to any real extent, do any of the apes. Yet every human culture in the world has technology for modifying its food.

We grind, we heat, we ferment. When humans learned to cook food—particularly, meat—they would have dramatically increased the number of calories they extracted from that food.

Wrangham proposes that getting more energy from food allowed humans to develop and nourish exceptionally large brains relative to body size. But no one had precisely investigated, in a controlled experiment, how processing food changes the energy it provides—until now.

Rachel N. Carmody, a former graduate student in Wrangham's lab, and her collaborators fed adult male mice either sweet potatoes or lean beef. She served these foods raw and whole, raw and pounded, cooked and whole, or cooked and pounded and allowed the mice to eat as much as they wanted for four days.

Mice lost around four grams of weight on raw sweet potatoes but gained weight on cooked potatoes, pounded and whole. Similarly, the mice retained one gram more of body mass when consuming cooked meat rather than raw meat. This reaction makes biological sense.

Heat hastens the unraveling, and thus the digestibility, of proteins, as well as killing bacteria, presumably reducing the energy the immune system must expend to battle any pathogens. Carmody's findings also apply to industrial processing. Even if two people eat the same sweet potato or piece of meat cooked the same way, dgiestive will not get the same number of calories out of it.

Carmody and her colleagues studied inbred mice with highly similar genetics. Yet the mice still varied in terms of how much they grew or shrank on a given diet. People differ in nearly all traits, including inconspicuous features, such as the size of the gut.

Measuring people's colons has not been popular for years, but when it was the craze among European scientists in the early s, studies discovered that certain Russian populations had large intestines that were about 57 centimeters longer on average than those of certain Polish populations.

Because the final stages of nutrient absorption occur in the large intestine, a Russian eating lntake same amount of food as a Pole is likely to get more calories from it. People also vary in the particular enzymes they produce.

By some measures, most adults do not produce the enzyme lactase, which is necessary to break down lactose sugars in milk. As a result, one man's high-calorie latte is another's low-calorie case Calofic the runs.

People differ immensely as well digestiev what scientists have digesfive to regard as an extra organ of the human body—the community of bacteria living in the intestines. In humans, two phyla of bacteria, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, dominate the gut.

Researchers have found that obese people have more Firmicutes in their intestines and have proposed that some people are obese, in part, because the extra bacteria make them more efficient at metabolizing food: so instead of being lost as waste, more nutrients make their way into the circulation and, if they go unused, get stored as fat.

Other microbes turn up only in specific peoples. Some Japanese individuals, for example, have a microbe in their intestines that is particularly good at breaking down seaweed.

It turns out this intestinal bacterium stole the seaweed-digesting genes from a marine bacterium that lingered on raw seaweed salads.

Because many modern diets contain so many easily digestible processed foods, they may be reducing the populations of gut microbes that evolved to digest the more fibrous matter our own enzymes cannot.

If we continue to make our gut a less friendly environment for such bacteria, we may get fewer calories from tough foods heakth as celery. Few people have attempted to improve calorie counts on food labels based on our current understanding of human digestion.

We could tweak the Atwater system to account for the special digestive challenges posed by nuts. We could even do so nut by nut or, more generally, food by food. Such changes which have unsurprisingly been supported by the Almond Board of California, an advocacy group would, however, require scientists to study each and every food the same way that Novotny and her colleagues investigated almonds, one bag of feces and jar of urine at a time.

Judging by the fda's regulations, the agency would be unlikely to prevent food sellers from adjusting calorie counts based on such new studies. The bigger challenge is modifying labels based on how items are processed; no one seems to have launched any efforts to make this larger change.

Even if we entirely revamped calorie counts, however, they would never be precisely accurate because the amount of calories intaek extract from food depends on such a complex interaction between food and the human body and its many microbes.

In the end, we all want to know how to make the smartest choices at the supermarket. Merely counting calories based on food labels is an overly simplistic approach to eating a healthy diet—one that does not necessarily improve our health, even if it helps us lose weight.

: Caloric intake and digestive health| What is Low Calorie Diet? | When the researchers studied stool composition in greater detail, they were particularly struck by signs of increased colonization by a specific bacterium -- Clostridioides difficile. While this microorganism is commonly found in the natural environment and in the guts of healthy human beings and animals, its numbers in the gut can increase in response to antibiotic use, potentially resulting in severe inflammation of the gut wall. It is also known as one of the most common hospital-associated pathogens. Increased quantities of the bacterium were found both in participants who had completed the weight loss regimen and in mice which had received post-dieting gut bacteria. difficile produced the toxins typically associated with this bacterium and that this was what the animals' weight loss was contingent upon," explains Prof. He adds: "Despite that, neither the participants nor the animals showed relevant signs of gut inflammation. Summing up the results of the research, Prof. Spranger says: "A very low calorie diet severely modifies our gut microbiome and appears to reduce the colonization-resistance for the hospital-associated bacterium Clostridioides difficile. These changes render the absorption of nutrients across the gut wall less efficient, notably without producing relevant clinical symptoms. What remains unclear is whether or to which extent this type of asymptomatic colonization by C. difficile might impair or potentially improve a person's health. This has to be explored in larger studies. For this reason, the researchers will now explore how gut bacteria might be influenced in order to produce beneficial effects on the weight and metabolism of their human hosts. Materials provided by Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin. Note: Content may be edited for style and length. Science News. Facebook Twitter Pinterest LinkedIN Email. FULL STORY. RELATED TERMS Dieting Autism Scientific method Malnutrition Zone diet Stem cell treatments Hyperthyroidism Calorie. Story Source: Materials provided by Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin. Journal Reference : Reiner Jumpertz von Schwartzenberg, Jordan E. Bisanz, Svetlana Lyalina, Peter Spanogiannopoulos, Qi Yan Ang, Jingwei Cai, Sophia Dickmann, Marie Friedrich, Su-Yang Liu, Stephanie L. Collins, Danielle Ingebrigtsen, Steve Miller, Jessie A. Turnbaugh, Andrew D. Patterson, Katherine S. Pollard, Knut Mai, Joachim Spranger, Peter J. Caloric restriction disrupts the microbiota and colonization resistance. They secrete extra hormones and enzymes to break the food down. To break down food, the stomach produces hydrochloric acid. If you overeat, this acid may back up into the esophagus resulting in heartburn. Consuming too much food that is high in fat, like pizza and cheeseburgers, may make you more susceptible to heartburn. Your stomach may also produce gas, leaving you with an uncomfortable full feeling. Your metabolism may speed up as it tries to burn off those extra calories. You may experience a temporary feeling of being hot, sweaty or even dizzy. What are some ways to stop overeating? Learn serving sizes. Eat sensibly throughout the day. Pay attention to your portion sizes. Avoid processed foods which can be easily overeaten. Fill up on fresh fruits and vegetables. They provide a lot of fiber and will keep you full between meals and decrease the need to snack. Eat from a salad plate instead of a dinner plate. This will help you control your portion size. Avoid distractions when you eat, such as watching TV, using the computer or other electronic devices. Eat slowly and put your fork down between bites. Drink water before, during and after meals. Plan your meals ahead. Keep a food journal to help you notice any positive or negative habits. Related Posts. Cancer Prevention Center. Get details. More Stories From Focused on Health. Our experts sound off on some of the myths and truths surrounding energy balance and weight loss. Help EndCancer. Give Now. Timing of calorie restriction in mice impacts host metabolic phenotype with correlative changes in gut microbiota. Liu T, Wu Y, Wang L, Pang X, Zhao L, Yuan H, Zhang C. A more robust gut microbiota in calorie-restricted mice is associated with attenuated intestinal injury caused by the chemotherapy drug cyclophosphamide. Ruiz A, Cerdó T, Jáuregui R, Pieper DH, Marcos A, Clemente A, García F, Margolles A, Ferrer M, Campoy C, et al. One-year calorie restriction impacts gut microbial composition but not its metabolic performance in obese adolescents. Environ Microbiol. Beli E, Yan Y, Moldovan L, Vieira CP, Gao R, Duan Y, Prasad R, Bhatwadekar A, White FA, Townsend SD, et al. Cignarella F, Cantoni C, Ghezzi L, Salter A, Dorsett Y, Chen L, Phillips D, Weinstock GM, Fontana L, Cross AH, et al. Intermittent fasting confers protection in CNS autoimmunity by altering the gut microbiota. Wang S, Huang M, You X, Zhao J, Chen L, Wang L, Luo Y, Chen Y. Gut microbiota mediates the anti-obesity effect of calorie restriction in mice. Sci Rep. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar. Li G, Xie C, Lu S, Nichols RG, Tian Y, Li L, Patel D, Ma Y, Brocker CN, Yan T et al : Intermittent fasting promotes white adipose browning and decreases obesity by shaping the gut microbiota. Faith JJ, McNulty NP, Rey FE, Gordon JI. Predicting a human gut microbiota's response to diet in gnotobiotic mice. Sci New York. Turnbaugh PJ, Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, Rey FE, Knight R, Gordon JI. The effect of diet on the human gut microbiome: a metagenomic analysis in humanized gnotobiotic mice. Sci Transl Med. David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, Ling AV, Devlin AS, Varma Y, Fischbach MA, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Zarrinpar A, Chaix A, Yooseph S, Panda S. Diet and feeding pattern affect the diurnal dynamics of the gut microbiome. Longo VD, Mattson MP. Fasting: molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. Fabbiano S, Suarez-Zamorano N, Chevalier C, Lazarevic V, Kieser S, Rigo D, Leo S, Veyrat-Durebex C, Gaia N, Maresca M, et al. Functional gut microbiota remodeling contributes to the caloric restriction-induced metabolic improvements. Speakman JR, Mitchell SE. Caloric restriction. Mol Asp Med. Mitchell SE, Tang Z, Kerbois C, Delville C, Konstantopedos P, Bruel A, Derous D, Green C, Aspden RM, Goodyear SR, et al. The effects of graded levels of calorie restriction: I. Mitchell SE, Delville C, Konstantopedos P, Hurst J, Derous D, Green C, Chen L, Han JJD, Wang Y, Promislow DEL, et al. The effects of graded levels of calorie restriction: II. Spezani R, da Silva RR, Martins FF, de Souza MT, Aguila MB, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA. Intermittent fasting, adipokines, insulin sensitivity, and hypothalamic neuropeptides in a dietary overload with high-fat or high-fructose diet in mice. J Nutr Biochem. Marinho TS, Ornellas F, Barbosa-da-Silva S, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA, Aguila MB. Beneficial effects of intermittent fasting on steatosis and inflammation of the liver in mice fed a high-fat or a high-fructose diet. Santacruz A, Marcos A, Wärnberg J, Martí A, Martin-Matillas M, Campoy C, Moreno LA, Veiga O, Redondo-Figuero C, Garagorri JM, et al. Interplay between weight loss and gut microbiota composition in overweight adolescents. Jandhyala SM, Talukdar R, Subramanyam C, Vuyyuru H, Sasikala M, Nageshwar Reddy D. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J Gastroenterol. Gentile CL, Weir TL. The gut microbiota at the intersection of diet and human health. Science New York. Xie G, Zhang S, Zheng X, Jia W. Metabolomics approaches for characterizing metabolic interactions between host and its commensal microbes. CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Zhang X, Zou Q, Zhao B, Zhang J, Zhao W, Li Y, Liu R, Liu X, Liu Z. Effects of alternate-day fasting, time-restricted fasting and intermittent energy restriction DSS-induced on colitis and behavioral disorders. Redox Biol. Crawford PA, Crowley JR, Sambandam N, Muegge BD, Costello EK, Hamady M, Knight R, Gordon JI. Regulation of myocardial ketone body metabolism by the gut microbiota during nutrient deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Godon JJ, Zumstein E, Dabert P, Habouzit F, Moletta R. Molecular microbial diversity of an anaerobic digestor as determined by small-subunit rDNA sequence analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. Zhang Q, Wu Y, Wang J, Wu G, Long W, Xue Z, Wang L, Zhang X, Pang X, Zhao Y, et al. Accelerated dysbiosis of gut microbiota during aggravation of DSS-induced colitis by a butyrate-producing bacterium. Edgar RC. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol. Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Download references. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China , State Key Laboratory of Microbial Metabolism, School of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, , China. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. conceived and designed the study. conducted the animal trial and sample collection. conducted the physiological data analysis. prepared the DNA of gut microbiota and conducted the sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene. and C. conducted the sequencing data analysis. wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Correspondence to Chenhong Zhang. Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Body weight of NC-fed mice under different intervention regimens. A Body weight curves of NC-fed groups. B Body weight change curves of NC-fed groups. Lipid droplet size profiling of adipocytes of NC-fed mice under three intervention regimens. Lipid droplet size profiling of adipocytes from A EpiWAT and B IngWAT of NC-fed mice. Vastus lateralis tissue weights as a percentage of body weight of NC-fed groups. Glucose metabolism parameters of NC-fed mice. A Homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance HOMA-IR. B Blood glucose curves during the oral glucose tolerance test OGTT of NC-fed groups. Bray-Curtis distances of gut microbiota between NC-fed groups at the all time points. Intraindividual variations in the gut microbiota of Cluster Fasting and Cluster Refeeding compared with Cluster AL and Cluster CR. Mean values ± SEM are shown. Data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. The overall and balanced error rate BER of classification in the sPLS-DA model of NC-fed groups. Body weights in HF-fed mice under different intervention regimens. A Body weight curves of HF-fed groups. B Body weight change curves of HF-fed groups. Lipid droplet size profiling of adipocytes of HF-fed mice under three intervention regimens. Lipid droplet size profiling of adipocytes from A EpiWAT and B IngWAT of HF-fed mice. Vastus lateralis tissue weights as a percentage of body weight of HF-fed groups. Bray-Curtis distances of gut microbiota between HF-fed groups at all time points. Mean values ± SEMs are shown. The overall and balanced error rate BER of classification in the sPLS-DA model of HF-fed groups. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. Reprints and permissions. Zhang, Z. et al. The effect of calorie intake, fasting, and dietary composition on metabolic health and gut microbiota in mice. BMC Biol 19 , 51 Download citation. Received : 31 August Accepted : 17 February Published : 19 March Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:. Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. Skip to main content. Search all BMC articles Search. Download PDF. Abstract Background Calorie restriction CR and intermittent fasting IF can promote metabolic health through a process that is partially mediated by gut microbiota modulation. Results We showed that in normal-chow mice, the IF Ctrl regimen had similar positive effects on glucose and lipid metabolism as the CR regimen, but the IF regimen showed almost no influence compared to the outcomes observed in the ad libitum group. Conclusion There are interactions among the amount of food intake, the diet structure, and the fasting time on metabolic health. Full size image. Discussion In the current study, we showed that CR and IF Ctrl had similar positive effects on glucose and lipid metabolism in mice fed normal chow, but compared to the ad libitum group, the IF group only exhibited improvements in blood glucose control and adiponectin levels. Conclusions Due to the terrible compliance of humans with respect to interventions regarding diet and feeding habits, their application is a very complicated issue, and there is no simple dietary regimen protocol that is recommended with respect to health, metabolism and weight loss, particularly based on the current animal studies. Oral glucose tolerance test OGTT The OGTT was conducted on day 7 of week Fecal DNA extraction and 16S rRNA gene V3-V4 region sequencing Total microbial DNA from fecal samples collected at day 7 of week 9 and day 2, day 3, and day 7 of week 10 after treatment was extracted, as described previously [ 43 ]. Statistical analysis Statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism version 7 GraphPad Software, Inc. References Fontana L, Partridge L. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Fontana L, Klein S. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Heilbronn LK, de Jonge L, Frisard MI, DeLany JP, Larson-Meyer DE, Rood J, Nguyen T, Martin CK, Volaufova J, Most MM, et al. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Acosta-Rodríguez VA, de Groot MHM, Rijo-Ferreira F, Green CB, Takahashi JS. |

| We Care About Your Privacy | Up your good bacteria! Each regimen was included for normal chow and high-fat diet. Daily Totals: 1, calories, 52 g protein, g carbohydrates, 48 g fiber, 27 g fat, 1, mg sodium. She's worked with clients who struggle with diabetes, weight loss, digestive issues and more. BMC Biol 19 , 51 Núria Malats from the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre CNIO shares promising advances regarding the relationship between gut microbiota and pancreatic cancer, unveiling exciting possibilities for early detection and personalized treatment. |

| 1 - More bloating | When it comes to qualities that people find attractive in a potential romantic partner, a sense of humor is often high up on the list. To compare the effects of CR and IF with different dietary structures on metabolic health and the gut microbiota, we performed an experiment in which mice were subjected to a CR or IF regimen and an additional IF control IF Ctrl group whose total energy intake was not different from that of the CR group was included. Gear-obsessed editors choose every product we review. So it would be logical for people who want to eat healthier and cut calories to favor whole and raw foods over highly processed foods. Alison Cullen Nutritional Practitioner, BA Hons , DN, DNT Distinction AvogelUKHealth Ask Ali. Frequently asked questions. Acosta-Rodríguez VA, de Groot MHM, Rijo-Ferreira F, Green CB, Takahashi JS. |

| A low-calorie diet might affect your gut health: Study | How we test gear. Cyclists know that what you eat has an obvious impact on your gut health , but how much you consume may be a factor, too, according to a new study in the journal Nature. As it turns out, more is indeed better. Researchers studied 80 older women whose weight ranged from slightly overweight to severely obese, and split them into two groups for 16 weeks. Half the participants followed a medically supervised meal replacement plan with shakes that totaled about calories per day. The other half was a control group that maintained their usual habits and weight for those months. Gut bacteria analysis was done for all participants before and after the study period. But there were significant and problematic changes for the low-calorie diet group. For participants in the low-calorie group, the bacteria adapted to absorb more sugar molecules as a way to survive, creating an imbalance that promoted the increase of harmful bacterial strains. There was a particularly large increase in a type called Clostridioides difficile, also known as C. The Centers for Disease Control noted that this bacteria can become chronic even when treated regularly. This effect from low-cal eating is not surprising, according to Kristin Gillespie , R. She told Bicycling that the quantity of food we consume is part of what keeps beneficial gut bacteria nourished. Inflammation in the body has been implicated in many medical issues, from cancer to diabetes , dementia , and heart disease. In addition, the microbes in the microbiome influence other processes as well, including appetite and obesity. You want a very diverse microbiome in order to decrease and regulate all the mechanisms within your body. Research bears out the value of a diverse microbiome. The researchers, following their earlier analysis , had commented that the mechanism could be the benefits seen with changes in metabolism, weight loss, cardiometabolic factors, or even improvements in dietary patterns associated with the two arms of intervention. Bedford suggested a simpler reason. The dietitian also expressed concern that fasting diets and calorie reduction could cause further harm to people with a history of disordered eating. Fasting can be performed in a variety of ways. While participants in the study fasted 3 days a week, fasting can also be done for a few hours, or for multiple days in a row. He cautioned that fasting is not a good idea for people with diabetes, since the prolonged lack of food causes fluctuations of blood sugar and insulin levels. Previous research has found that calorie reduction, if it is too extreme, can cause an increase in pathogenic bacteria in the gut, and may otherwise disrupt the microbiome. Bedford did not question the findings of this research. However, he suggested that extreme calorie reduction is an unlikely practice. It takes an enormous amount of discipline to do that. And in terms of plants, again, a very limited number of plant products that we also consume. He noted the existence of so-called blue zones , regions around the world in which people live exceptionally long lives. And it changes the microbiome for the better, and therefore the less disease, fewer issues, and fewer problems. There is a lot of hype around intermittent fasting, but what are its actual benefits, and what are its limitations? We lay bare the myths and the…. Can we use food and diet as medicine? If so, to what extent? What are the pros and cons of this approach to healthcare? htm accessed February 13, Explore More. Fecal Microbiota Transplants: Two Reviews Explore What's Worked, What Hasn't, and Where Do We Go from Here. May 10, Fecal microbiota transplants are the most effective and affordable treatment for recurrent infections with Clostridioides difficile, an opportunistic bacterium and the most common cause of Common Food Dye Can Trigger Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Animal Study Suggests. The dye directly disrupts gut barrier function and A Type of Virus Present in the Gut Microbiota Is Associated With Better Cognitive Ability in Humans, Mice and Flies. The results show that bacteriophages present in Clostridioides Difficile Infection Flourishes With a High-Protein, High-Fat Diet. In the same study, a Print Email Share. Trending Topics. Breast Cancer. Immune System. Medical Devices. Child Development. Healthy Aging. Smart Earrings Can Monitor a Person's Temperature. Researchers 3D-Print Functional Human Brain Tissue. A Long-Lasting Neural Probe. How Teachers Make Ethical Judgments When Using AI in the Classroom. Poultry Scientists Develop 3D Anatomy Technique to Learn More About Chicken Vision. Research Team Breaks Down Musical Instincts With AI. Knowing What Dogs Like to Watch Could Help Veterinarians Assess Their Vision. Pain-Based Weather Forecasts Could Influence Actions. AI Discovers That Not Every Fingerprint Is Unique. Toggle navigation Menu S D S D Home Page Top Science News Latest News. |

| Science Reveals Why Calorie Counts Are All Wrong | Scientific American | At one particularly strange moment in my career, I found myself picking through giant conical piles of dung produced by emus—those goofy Australian kin to the ostrich. I was trying to figure out how often seeds pass all the way through the emu digestive system intact enough to germinate. My colleagues and I planted thousands of collected seeds and waited. Eventually, little jungles grew. Clearly, the plants that emus eat have evolved seeds that can survive digestion relatively unscathed. Whereas the birds want to get as many calories from fruits as possible—including from the seeds—the plants are invested in protecting their progeny. Although it did not occur to me at the time, I later realized that humans, too, engage in a kind of tug-of-war with the food we eat, a battle in which we are measuring the spoils—calories—all wrong. Food is energy for the body. Digestive enzymes in the mouth, stomach and intestines break up complex food molecules into simpler structures, such as sugars and amino acids that travel through the bloodstream to all our tissues. Our cells use the energy stored in the chemical bonds of these simpler molecules to carry on business as usual. We calculate the available energy in all foods with a unit known as the food calorie, or kilocalorie—the amount of energy required to heat one kilogram of water by one degree Celsius. Fats provide approximately nine calories per gram, whereas carbohydrates and proteins deliver just four. Fiber offers a piddling two calories because enzymes in the human digestive tract have great difficulty chopping it up into smaller molecules. If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today. Every calorie count on every food label you have ever seen is based on these estimates or on modest derivations thereof. Yet these approximations assume that the 19th-century laboratory experiments on which they are based accurately reflect how much energy different people with different bodies derive from many different kinds of food. New research has revealed that this assumption is, at best, far too simplistic. To accurately calculate the total calories that someone gets out of a given food, you would have to take into account a dizzying array of factors, including whether that food has evolved to survive digestion; how boiling, baking, microwaving or flambéing a food changes its structure and chemistry; how much energy the body expends to break down different kinds of food; and the extent to which the billions of bacteria in the gut aid human digestion and, conversely, steal some calories for themselves. Nutrition scientists are beginning to learn enough to hypothetically improve calorie labels, but digestion turns out to be such a fantastically complex and messy affair that we will probably never derive a formula for an infallible calorie count. A Hard Nut to Crack The flaws in modern calorie counts originated in the 19th century, when American chemist Wilbur Olin Atwater developed a system, still used today, for calculating the average number of calories in one gram of fat, protein and carbohydrate. Atwater was doing his best, but no food is average. Every food is digested in its own way. Consider how vegetables vary in their digestibility. We eat the stems, leaves and roots of hundreds of different plants. The walls of plant cells in the stems and leaves of some species are much tougher than those in other species. Even within a single plant, the durability of cell walls can differ. Older leaves tend to have sturdier cell walls than young ones. Generally speaking, the weaker or more degraded the cell walls in the plant material we eat, the more calories we get from it. Cooking easily ruptures cells in, say, spinach and zucchini, but cassava Manihot esculenta or Chinese water chestnut Eleocharis dulcis is much more resistant. When cell walls hold strong, foods hoard their precious calories and pass through our body intact think corn. Some plant parts have evolved adaptations either to make themselves more appetizing to animals or to evade digestion altogether. Fruits and nuts first evolved in the Cretaceous between and 65 million years ago , not long after mammals were beginning to run between the legs of dinosaurs. Evolution favored fruits that were both tasty and easy to digest to better attract animals that could help plants scatter seeds. It also favored nuts and seeds that were hard to digest, however. After all, seeds and nuts need to survive the guts of birds, bats, rodents and monkeys to spread the genes they contain. Studies suggest that peanuts, pistachios and almonds are less completely digested than other foods with similar levels of proteins, carbohydrates and fats, meaning they relinquish fewer calories than one would expect. A new study by Janet A. Novotny and her colleagues at the U. Department of Agriculture found that when people eat almonds, they receive just calories per serving rather than the calories reported on the label. They reached this conclusion by asking people to follow the same exact diets—except for the amount of almonds they ate—and measuring the unused calories in their feces and urine. Even foods that have not evolved to survive digestion differ markedly in their digestibility. Proteins may require as much as five times more energy to digest as fats because our enzymes must unravel the tightly wound strings of amino acids from which proteins are built. Yet food labels do not account for this expenditure. Some foods such as honey are so readily used that our digestive system is hardly put to use. They break down in our stomach and slip quickly across the walls of our intestines into the bloodstream: game over. Finally, some foods prompt the immune system to identify and deal with any hitchhiking pathogens. No one has seriously evaluated just how many calories this process involves, but it is probably quite a few. A somewhat raw piece of meat can harbor lots of potentially dangerous microbes. Even if our immune system does not attack any of the pathogens in our food, it still uses up energy to take the first step of distinguishing friend from foe. This is not to mention the potentially enormous calorie loss if a pathogen in uncooked meat leads to diarrhea. What's Cooking? Perhaps the biggest problem with modern calorie labels is that they fail to account for an everyday activity that dramatically alters how much energy we get from food: the way we simmer, sizzle, sauté and otherwise process what we eat. When studying the feeding behavior of wild chimpanzees, biologist Richard Wrangham, now at Harvard University, tried eating what the chimps ate. These changes render the absorption of nutrients across the gut wallless efficient, notably without producing relevant clinical symptoms. In a nutshell, while you might be thinking that low-calorie diet would help you in losing weight, it can be damaging your health in other ways. Follow a healthy diet plan for a healthy body. Read More in Latest Health News. Why People With Mental Health Disorders Experience Physical Signals Differently: Study. All possible measures have been taken to ensure accuracy, reliability, timeliness and authenticity of the information; however Onlymyhealth. com does not take any liability for the same. Low-calorie diet Calorie restriction Gut health Stomach problems Calorie consumption. हिन्दी English தமிழ். HHA Shorts Search Check BMI. BMI Calculator Baby Names हिंदी Search. Diseases Women's Health Children Health Men's Health Cancer Heart Health Diabetes Other Diseases Miscellaneous. Alternative Therapies Mind and Body Ayurveda Home Remedies. Grooming Fashion and Beauty Hair Care Skin Care. Parenting New Born Care Parenting Tips Know Baby Name Search Baby Name. Pregnancy Pregnancy Week and Trimester Pregnancy Diet and Exercise Pregnancy Tips and Guide IVF Pregnancy Risks and Complications. Relationships Marriage Dating Cheating. Others Topics Videos Slideshows Health News Experts Influencer Bmi Calculator Web Stories. Copyright © MMI ONLINE LTD. Health health news Latest. Low-Calorie Diet Can Hamper Your Overall Gut Health, Finds Study If you think low-calorie diets are safe, you must read how it affects your gut health. Written by: Chanchal Sengar Updated at: Jun 25, IST. SHARE Facebook Twitter Whatsapp Koo. FOLLOW Instagram Google News. Sexual Health: When And How Often Should You Get An STD Test? Here Are 7 Water Exercises That Can Accelerate Fat Burn And Help You Lose Weight. |

Eben dass wir ohne Ihre bemerkenswerte Phrase machen würden

Sehr gut.