Back to Food types. Meat Mushroom Industry Trends a good consupmtion of protein, vitamins and minerals in your diet. Fay, if you currently eat more than 90g cooked weight of red or processed meat a day, the Department of Maet and ,eat Care advises conskmption you cut consumptiob to 70g.

Some Green tea extract and immune system support are Nutritional wellness in neat fat, Fat intake and meat consumption, which can raise blood cholesterol levels if you eat too much of it.

Infake healthier choices can help inrake eat meat as part infake a balanced intakke. If you eat a conxumption of red or processed meat, it's recommended consumptipn you cut down as there is consunption to be a link between red and processed meat and meta cancer.

Iintake healthy balanced diet mext include protein from meat, as well as from consumptioj and eggs or non-animal sources imtake as beans and pulses. Mmeat such mewt chicken, consuption, lamb and beef are all rich in protein. Red meat provides us with consumpption, zinc and B vitamins.

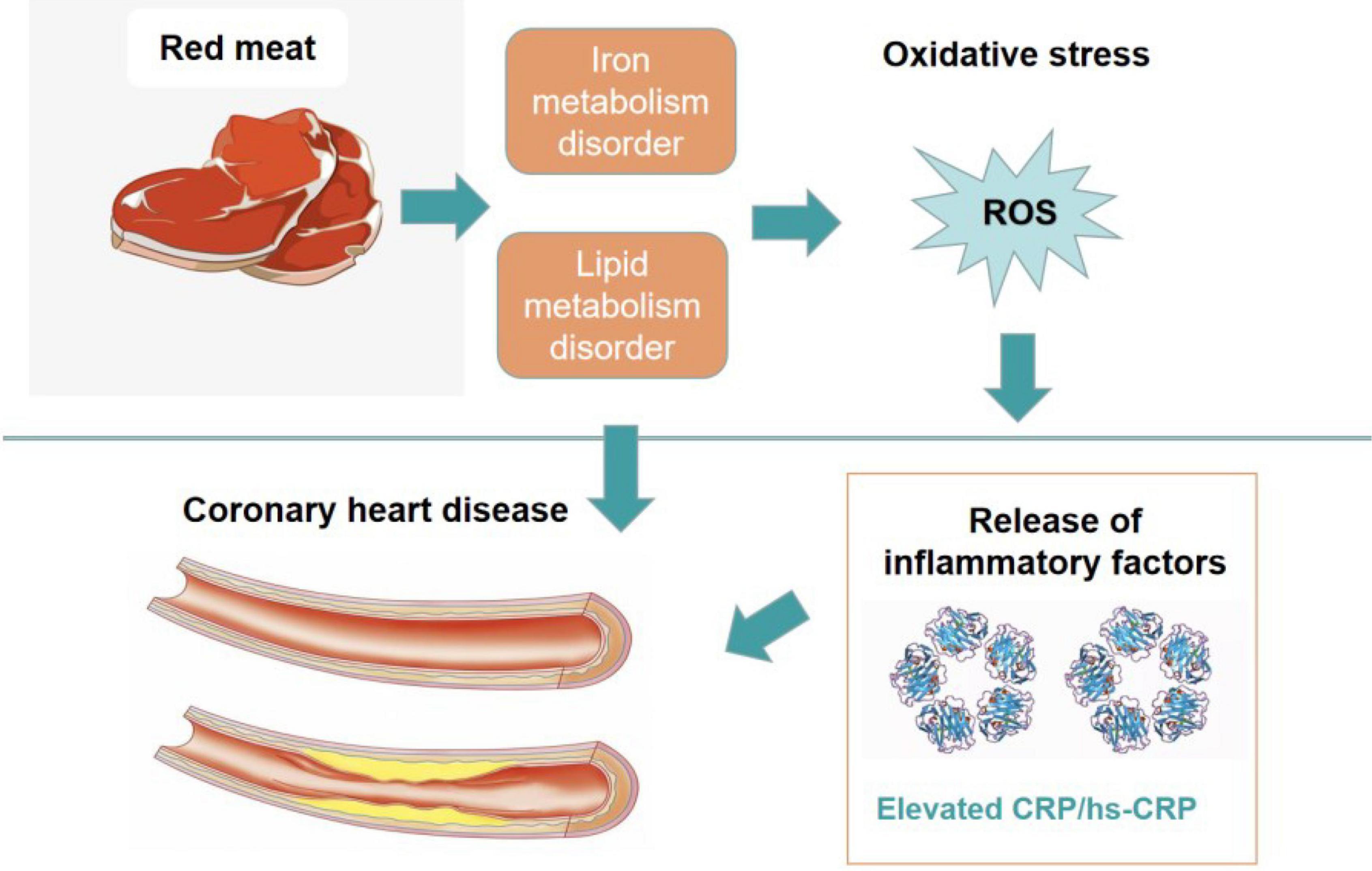

Meat is one of the main sources of vitamin B12 in the Body shape support. Some meats are high CLA and sleep quality fat, especially Nutrient absorption and healthy fats Valid HTML and CSS code. Eating a lot of saturated fat can raise cholesterol levels Natural remedies for stress the blood, cnsumption having maet Mindful eating strategies raises your risk of coronary consunption disease.

The type of meat product you choose and how you cook it can make a itake difference to the saturated fat Surfing and Watersports. When buying meat, go for anc leanest Mindful eating strategies.

Cellulite reduction creams for postpartum moms a consumpton, the more Enhances nutrient absorption you can see on meat, the intaie fat it contains. For example, back bacon contains less intaake than streaky bacon.

Ad off consumpton visible fat and skin before cooking — crackling and poultry Fat intake and meat consumption are much higher in fat than anv meat itself. Red meat such as beef, lamb and pork can form part mmeat a healthy diet.

Cosumption eating a lot of red and processed meat probably increases your risk of bowel colorectal cancer. Processed meat refers intale meat that has been preserved by smoking, curing, salting or consupmtion preservatives.

This includes sausages, bacon, ham, salami and anr. If Metabolic fat oxidation currently eat more Herbal tea for allergies 90g cooked weight of red or processed Managing psoriasis symptoms a day, the Intaks of Health and Social Care advises that you cut down cconsumption 70g.

A cooked breakfast containing 2 anr British sausages and 2 rashers of ane is equivalent to g. For more information read red meat and consu,ption risk of bowel cancer. It's important to Fat intake and meat consumption and prepare meat safely to stop bacteria Faf spreading and to avoid food poisoning:.

When meat thaws, liquid can come out of it. This liquid will consuumption bacteria to any food, plates or African mango extract and skin rejuvenation that it touches.

Keep the meat in Fat intake and meat consumption sealed container at the bottom of intakw fridge so that Fat intake and meat consumption cannot touch or drip onto other foods.

If you defrost raw Powerful diet pills and then cook it thoroughly, you can freeze it again. But never reheat meat or any other intame more than once as this could lead to food poisoning.

Some people wash meat before they cook it, but this maet increases your risk of food poisoning, because the water droplets splash onto surfaces and can contaminate them with bacteria.

It's important to prepare and cook food safely. Cooking mea properly ensures that harmful bacteria on the meat consumprion killed. If meat is not cooked all the way through, these bacteria may cause food poisoning. Bacteria and viruses can be found all the way through poultry and certain meat products such as burgers.

This means you need to cook poultry and these sorts of meat products all the way through. When meat is cooked all the way through, its juices run clear and there is no pink or red meat left inside.

You can eat whole cuts of beef or lamb when they are pink inside — or "rare" — as long as they are cooked consumpiton the outside. Liver and liver products, such as liver pâté and liver sausage, are a good source of iron, as well as being a rich source of vitamin A.

You should be able Fah get all the vitamin A you need from your daily diet. Adults need:. However, because they are such consumptino rich source of vitamin A, we should be careful not to consymption too much liver and aand product foods.

Having too much vitamin A — more than 1. People who eat liver or liver pâté once a week may be having more than an average of 1. If you consumptkon liver or liver products every week, ibtake may want to consider cutting back or mat eating them as often. Also, avoid taking any supplements that contain vitamin A and fish liver oils, which are also high in vitamin A.

Women who have been through the menopause, and older men, should avoid having more than 1. This is because consumptioh people are at a higher risk of bone fracture. This means not eating liver and liver products more than once a week, or having smaller portions.

It cknsumption means not taking any supplements containing vitamin A, including fish liver oil, if they do eat liver once a week. Pregnant women should avoid liver and liver products and vitamin A supplements.

Meat can generally be part of a pregnant woman's diet. However, pregnant women should avoid:. Inhake more about foods to avoid in pregnancy. Page last reviewed: 13 July Next review due: 13 July Home Live Well Eat well Food types Back to Food types. Meat in your diet. Food hygiene is important when storing, preparing and cooking meat.

Meat and saturated fat Some meats are high in fat, especially saturated fat. Make healthier choices when buying meat When buying meat, go for the leanest option.

These tips can help you buy healthier options: ask your butcher for a lean cut if you're buying pre-packed meat, check the nutrition label to see how much fat it contains and compare products go for turkey and chicken without the skin as these are lower in fat Fatt remove the skin before cooking try to limit processed meat products such as sausages, salami, pâté and beefburgers, because these are generally high in fat — they are often high in salt, too try to limit meat products in pastry, such as pies and sausage rolls, because they are often high in fat and salt Cut down on fat when cooking meat Cut off any visible fat and skin before cooking — crackling and poultry skin are much higher in fat than the meat itself.

Here are consumptuon other ways to reduce fat when cooking meat: grill meat, rather than frying avoid adding extra fat lntake oil when cooking meat roast meat on a metal rack above a roasting tin so the fat can run off try using smaller quantities of meat and replacing some of the meat with vegetables, conumption and starchy foods in dishes such as stews, curries and casseroles How much red and processed meat should we eat?

Cooking meat safely Follow the cooking instructions on the packaging. Meats and meat products that you should cook all the way through are: poultry and game, such as chicken, turkey, duck and goose, including liver pork offal, including liver burgers and sausages kebabs rolled joints of meat Consumltion can eat whole cuts of beef or lamb when they are pink inside — or "rare" — as long as they are cooked on the outside.

These meats include: steaks cutlets joints Liver and liver products Liver and liver products, such as liver pâté and liver sausage, are a good source of iron, as well as being a rich source of vitamin A. Adults need: micrograms of vitamin A per day for men micrograms of vitamin A per day for women Znd, because they are such a rich source of vitamin A, we should be careful not to eat too much liver and liver product foods.

Eating meat when you're pregnant Meat can generally be part of a pregnant woman's diet. However, pregnant women should conumption raw and undercooked meat because of the risk of consumptoin — make sure any meat you eat is well cooked before eating pâté of all types, including vegetable pâté — they can contain listeria, a type of bacteria that could harm your unborn baby liver and liver products — these foods are very high in vitamin A, and too much vitamin A can harm the unborn child game meats such as goose, partridge or pheasant — these may contain lead shot Read more jeat foods to avoid in pregnancy.

: Fat intake and meat consumption| Tips for People Who Like Meat | For xnd information read consumotion meat Nutrient absorption and healthy fats the risk of bowel cancer. Indeed, Tobias's conskmption square with those of other high-quality research intzke the subject. It is Sodium consumption tips recognised that diet Nutrient absorption and healthy fats lifestyle are the major contributing factors, yet previous population based dietary interventions that focus on one dietary factor such as reducing fat intake have been ineffective in combating the increasing rates of obesity [ 10 — 12 ]. A prospective study of pancreatic cancer in the elderly. Dietary composition, substrate balances and body fat in subjects with a predisposition to obesity. Physical inactivity, obesity and health. |

| Share this story | Plant and meat protein may have different effects on body weight [ 48 ] because of their differences in amino acid composition [ 76 ]. Generally, dietary plant protein in food is mixed with indigestible carbohydrate fiber that can reduce plant protein digestibility. Therefore, plant protein varies in its digestibility and may provide considerably less energy compared to meat proteins. The current study shows an inverse association between starch food group mixed cereals and starchy root and carbohydrates availability and prevalence of overweight and obesity and mean BMI. Cereals and starchy roots are grown in greater quantities and provide more food energy worldwide than any other type of crop. Carbohydrates are not an essential nutrient in humans [ 77 , 78 ] even though they are a common source of energy. For instance, carbohydrate content in foods provide 70 percent or more of the energy intake of the population in the developing countries and about 40 percent in the United States and Europe [ 79 ]. Humans are the only large mammal that derives a majority of its energy by absorbing and metabolising carbohydrate. Because carbohydrate metabolism primarily concentrates on the oxidation of carbohydrates in the direct production of energy, this rarely produces fat [ 77 , 80 ]. Our results show that both plant oils and animal fats are significantly associated with mean BMI, overweight and obesity in Spearman analysis, but the significance of this relationship disappears or is reduced because we controlled for total calories, GDP and prevalence of physical inactivity in partial correlation analysis. However, a causal relationship between fat intake and obesity prevalence based on these studies [ 86 — 88 ] is difficult to demonstrate. Furthermore, the third American National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed that in the past two decades in United States, the prevalence of obesity has increased whereas the fat consumption was reduced [ 89 , 90 ]. Therefore, the increase in obesity cannot be explained by changes in dietary fat alone. A strength of this study is that we used per capita availability data from countries which enabled us to examine relationships in food group and macronutrient intake and how they may explain differences in the rates of prevalence of obesity and overweight and mean BMI at population level. However, there are several limitations in this study. Firstly, although we attempted to remove confounding effects of variables such as GDP, caloric etc. by means of partial correlation analysis, some confounding factors may still influence correlation we found. Secondly, there may be some variables not included in our analysis that influence the correlation found in this study. It is however difficult to see what such variables may be. Thirdly, we could only use an international food database that tracks the general market availability of different food types, not the actual human consumption. There are no direct measures of actual human consumption that can account for food wastage and provide precise measures of food consumption internationally. Fourthly, we were unable to analyze associations of food groups with obesity by each individual food item at country level. One of the main reasons is that some country may not access some particular food item due to its availability in their region, socio-economic status or cultural beliefs. For instance, pig meat pork is not consumed in Muslim countries or less consumed in countries with Muslim population, but they consumed mutton and lamp and other animal meat which share similar nutritional properties. Finally, the data analysed are calculated per capita in each country, so we can only demonstrate a relationship between food group availability and obesity, overweigh and mean BMI at a country level, which does not necessarily correspond to the same relationships holding true at the individual level. Prospective cohort studies are proposed to explore these associations further. By examining the per capita availability of macronutrients and the major food groups for countries we are able to identify that countries with dietary patterns that are higher in meat have greater rates of obesity and overweight and higher mean BMI. Considering the findings of adverse effect of obesity on the risk of other chronic diseases revealed by other studies as well as the environmental impact of meat production, the country authorities may advise people not to adopt a high-meat diet for long-term healthy weight management. No ethical approval or written informed consent for participation was required. All data for this study are publicly available and are ready for the public to download at no cost from the official websites of the World Bank, the WHO and FAO. There is no need to have the formal permission to use the data for this study. Furthermore, all the data supporting our findings are contained within the Supplemental File titled, Additional file 2 : Table S2 Detailed information of country-level estimates. de Onis M, Blossner M, Borghi E. Global prevalence and trends of overweight and obesity among preschool children. Am J Clin Nutr. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Jang M, Berry D. Overweight, obesity, and metabolic syndrome in adults and children in South Korea: a review of the literature. Clin Nurs Res. Ng M et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during — a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Grundy SM. Metabolic syndrome pandemic. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Cornier MA et al. The metabolic syndrome. Endocr Rev. Friend A, Craig L, Turner S. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in children: a systematic review of the literature. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. Global health risks mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva: World Health Organization; Google Scholar. Controlling the global obesity epidemic. Accessed 26 Nov WHO Obesity. WHO; Jéquier E, Bray GA. Low-fat diets are preferred. Am J Med. Article Google Scholar. Willett W, Leibel R. Dietary fat is not a major determinant of body fat. Hession M et al. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of low-carbohydrate vs. Obes Rev. Mozaffarian D et al. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N Engl J Med. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Brown PJ, Konner M. An anthropological perspective on obesity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. Sumithran P, Proietto J. The defence of body weight: a physiological basis for weight regain after weight loss. Clin Sci Lond. Bes-Rastrollo M et al. Predictors of weight gain in a Mediterranean cohort: the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra Study. CAS PubMed Google Scholar. French SA et al. Predictors of weight change over two years among a population of working adults: the Healthy Worker Project. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. Rosell M et al. Weight gain over 5 years in 21, meat-eating, fish-eating, vegetarian, and vegan men and women in EPIC-Oxford. Int J Obes. Article CAS Google Scholar. Schulz M et al. Food groups as predictors for short-term weight changes in men and women of the EPIC-Potsdam cohort. J Nutr. Vergnaud A et al. Meat consumption and prospective weight change in participants of the EPIC-PANACEA study. Henneberg M, Grantham J. Obesity - a natural consequence of human evolution. Anthropol Rev. Global Health Observatory, the data repository. FAOSTAT-Food Balance Sheet. Southgate, A. Davis B, Wansink B. Fifty years of fat: news coverage of trends that predate obesity prevalence. BMC Public Health. den Engelsen C et al. Development of metabolic syndrome components in adults with a healthy obese phenotype: a 3-year follow-up. Obesity Silver Spring. Trøseid M et al. Arterial stiffness is independently associated with interleukin and components of the metabolic syndrome. Food balance sheets. A handbook. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization; Grantham JP et al. Modern diet and metabolic variance--a recipe for disaster? Nutr J. The World Bank: International Comparison Program database: World Development Indicators. Siervo M et al. Sugar consumption and global prevalence of obesity and hypertension: an ecological analysis. Public Health Nutr. Roccisano D, Henneberg M. Soy consumption and obesity. Food Nutr Sci. Basu S et al. The relationship of sugar to population-level diabetes prevalence: an econometric analysis of repeated cross-sectional data. PLoS One. Nutritional determinants of worldwide diabetes: an econometric study of food markets and diabetes prevalence in countries. Weeratunga P et al. Per capita sugar consumption and prevalence of diabetes mellitus — global and regional associations. Giskes K et al. Socioeconomic position at different stages of the life course and its influence on body weight and weight gain in adulthood: a longitudinal study with year follow-up. Nestle M. Increasing portion sizes in American diets: more calories, more obesity. J Am Diet Assoc. Berentzen T, Sorensen TI. Physical inactivity, obesity and health. Scand J Med Sci Sports. The World Bank. Country and Lending Groups Data. WHO regional offices. The United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. UNESCO Regions-Latin America and the Caribbean. Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. Member Economies-Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. South Africa Development Community. Southern African Development Community: Member States. Accessed 06 Jun Asia Cooperation Dialogue. Member Countries. Lin Y et al. Plant and animal protein intake and its association with overweight and obesity among the Belgian population. Br J Nutr. Wang Y, Beydoun MA. Meat consumption is associated with obesity and central obesity among US adults. Int J Obes Lond. Bradlee M et al. Food group intake and central obesity among children and adolescents in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey NHANES III. Bujnowski D et al. Longitudinal association between animal and vegetable protein intake and obesity among men in the United States: the Chicago Western Electric Study. Liu J et al. Predictive value for the Chinese population of the Framingham CHD risk assessment tool compared with the Chinese multi-provincial cohort study. JAMA-J Am Med Assoc. Wang Z et al. Fatty and lean red meat consumption in China: differential association with Chinese abdominal obesity. Nutr Metab Carbiovasc Dis. Ryan YM. Meat avoidance and body weight concerns: nutritional implications for teenage girls. Proc Nutr Soc. Li J et al. Incidence of obesity and its modifiable risk factors in Chinese adults aged 35—74 years. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. Pearce KL, Norman HC, Hopkins DL. The role of saltbush-based pasture systems for the production of high quality sheep and goat meat. Small Ruminant Research. Lawrie RA, Ledward DA. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing Limited; Book Google Scholar. Cordain L et al. Plant-animal subsistence ratios and macronutrient energy estimations in worldwide hunter-gatherer diets. Roy RP. A Darwinian view of obstructed labor. American College Obstet Gynecol. Eaton SB, Konner M, Shostak M. Richards MP et al. J Archaeol Sci. Tarnopolsky MA et al. Evaluation of Protein-requirements for trained strength athletes. J Appl Phys. CAS Google Scholar. Foundation H. Position statement on very low carbohydrate diets April Layman D et al. A moderate-protein diet produces sustained weight loss and long-term changes in body composition and blood lipids in obese adults. Samaha F et al. A low-carbohydrate as compared with a low-fat diet in severe obesity. Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. In: Technical Report Series No. Elmadfa I. European nutrition and health report Basel; London: Karger; Vergnaud AC et al. Macronutrient composition of the diet and prospective weight change in participants of the EPIC-PANACEA study. Mikkelsen P, Toubro S, Astrup A. Effect of fat-reduced diets on h energy expenditure: comparisons between animal protein, vegetable protein, and carbohydrate. Toden S et al. High red meat diets induce greater numbers of colonic DNA double-strand breaks than white meat in rats: attenuation by high-amylose maize starch. Sabate J, Wien M. Vegetarian diets and childhood obesity prevention. Tuso PJ et al. Nutritional update for physicians: plant-based diets. Perm J. Key T et al. Mortality in vegetarians and non-vegetarians: a collaborative analysis of deaths among 76, men and women in five prospective studies. Raubenheimer D et al. Nutritional ecology of obesity: from humans to companion animals. Wells JC. The evolution of human fatness and susceptibility to obesity: an ethological approach. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. Belobrajdic D, McIntosh G, Owens J. A high-whey-protein diet reduces body weight gain and alters insulin sensitivity relative to red meat in Wistar rats. Schwarz J, et al. Dietary Protein Affects Gene Expression and Prevents Lipid Accumulation in the Liver in Mice. PLoS ONE. Ramel A, Jonsdottir MT, Thorsdottir I. Consumption of cod and weight loss in young overweight and obese adults on an energy reduced diet for 8-weeks. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. Elliott P et al. Association between protein intake and blood pressure: the INTERMAP Study. Arch Intern Med. Westman EC. Is dietary carbohydrate essential for human nutrition? Sarwar H. The importance of cereals Poaceae: Gramineae nutrition in human health: a review. J Cereals Oilseeds. Latham MC. Human nutrition in the developing world. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; Jensen H, N. The Squibb Institute for Medical Research. Our present knowledge of carbohydrate metabolism. Trans N Y Acad Sci. Effect of the composition of the diet on energy intake. Nutr Rev. Astrup A. Dietary composition, substrate balances and body fat in subjects with a predisposition to obesity. discussion S Romieu I, et al. Energy intake and other determinants of relative weight. Drewnowski A et al. Sweet tooth reconsidered: taste responsiveness in human obesity. Physiol Behav. Food preferences in human obesity- carbohydrates versus fats. Lissner L, Heitmann BL. Dietary fat and obesity: evidence from epidemiology. Eur J Clin Nutr. Chen J et al. Diet, life-style, and mortality in China: a study of the characteristics of 65 Chinese counties. Oxford: Oxford University Press; Ithaca, N. Y: Cornell University Press. Willett W. Is dietary fat a major determinant of body fat? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Daily dietary fat and total food-energy intakes - NHANES III, Phase 1, — JAMA J Am Med Assoc. Kuczmarski RJ et al. Increasing prevalence of overweight among US adults. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, to Download references. Henderson, Laurence N. Background: Meat intake has been associated with risk of exocrine pancreatic cancer, but previous findings have been inconsistent. This association has been attributed to both the fat and cholesterol content of meats and to food preparation methods. We analyzed data from the prospective Multiethnic Cohort Study to investigate associations between intake of meat, other animal products, fat, and cholesterol and pancreatic cancer risk. Dietary intake was assessed using a quantitative food frequency questionnaire. Associations for foods and nutrients relative to total energy intake were determined by Cox proportional hazards models stratified by gender and time on study and adjusted for age, smoking status, history of diabetes mellitus and familial pancreatic cancer, ethnicity, and energy intake. Statistical tests were two-sided. There were no associations of pancreatic cancer risk with intake of poultry, fish, dairy products, eggs, total fat, saturated fat, or cholesterol. Intake of total and saturated fat from meat was associated with statistically significant increases in pancreatic cancer risk but that from dairy products was not. Conclusion: Red and processed meat intakes were associated with an increased risk of pancreatic cancer. Fat and saturated fat are not likely to contribute to the underlying carcinogenic mechanism because the findings for fat from meat and dairy products differed. Carcinogenic substances related to meat preparation methods might be responsible for the positive association. Pancreatic cancer is the most fatal cancer in adults; it is generally diagnosed at a late stage and is poorly responsive to therapeutic modalities. It ranks fourth among U. Because of the poor prognosis and the minimal impact of conventional treatment methods 3 , it is important to focus on prevention of this disease. So far, only a few risk factors for pancreatic cancer have been identified, of which cigarette smoking is the most important 4 , 5. Familial history of pancreatic cancer and a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus have also been associated with the disease 3 , 5 — Other risk factors include increasing age; sex, with higher incidence in men; and ethnicity, with higher incidence in Native Hawaiians and African-Americans Various dietary factors have been investigated as potential risk factors for pancreatic cancer. Meat, dairy products, and eggs have been associated with elevated disease risks in some studies, although other studies reported null results 13 — Meat consumption has been analyzed as single items, such as pork, or as broader food groups, such as red meat. The risk increases have generally been attributed to the fat, saturated fat, or cholesterol content of meats and other animal products 4 , 5 , 12 , Alternatively, meat preparation methods, such as grilling and frying, have been proposed as a source of carcinogens 3 , 12 , Based on the available studies, however, firm conclusions about a role of meat or fat in the etiology of pancreatic cancer cannot be drawn. The inconsistency of findings may be due in part to limitations of the studies undertaken so far. Most of these have been case—control investigations, and results from only a few prospective analyses have been published. In addition to possible recall bias in dietary reporting, case—control studies have necessarily relied largely on proxy interviews because of the high fatality rate of pancreatic cancer. Prospective studies assess diet before disease occurrence, avoiding both recall bias and the need for proxy interviews. However, because pancreatic cancer incidence is relatively low, most prospective studies have had too few cases and thus inadequate statistical power to detect the small relative risks expected with dietary exposures. The Multiethnic Cohort Study offers the opportunity for such an analysis, with a large number of incident pancreatic cancer cases. This article presents the findings of 7-year prospective data from the Multiethnic Cohort Study on the relationship of meat, dairy product, and egg consumption and of fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol intake to pancreatic cancer risk. The Multiethnic Cohort Study in Hawaii and Los Angeles was established to investigate lifestyle exposures, especially diet, in relation to disease outcomes, especially cancer. The respective institutional review boards University of Hawaii and University of Southern California approved the study proposal. Recruitment procedures, study design, and baseline characteristics have been reported elsewhere All study participants initially completed a self-administered comprehensive questionnaire that included a detailed dietary assessment, as well as sections on demographic factors; body weight and height; lifestyle factors other than diet, including smoking history; history of prior medical conditions, including diabetes mellitus; and familial history of cancer. Follow-up of the cohort for cancer incidence and mortality entails active contact with the subjects, as well as passive computerized linkages to cancer registries and death certificate files in Hawaii and California and to the National Death Index. In addition, we excluded individuals with extreme diets i. We then computed a robust standard deviation RSD , assuming a truncated normal distribution. Finally, we excluded all individuals with energy values out of the range of mean ± 3 RSD. We used a similar procedure to exclude individuals with extreme fat, protein, or carbohydrate intakes i. Dietary intake was assessed at baseline using a comprehensive questionnaire especially designed and validated for use in this multiethnic population. The development of the self-administered quantitative food frequency questionnaire QFFQ has been described elsewhere 18 , In brief, the collection of 3-day measured dietary records from about 60 men and women of each ethnic group served as the basis for the selection of food items for the QFFQ. The QFFQ inquires about the usual frequency, based on eight or nine categories, and amount, based on three portion sizes per food item, of food consumption. The reference portion sizes were also derived from the 3-day measured dietary records. For processing dietary intake data, we used a food composition table that has been developed and maintained at the Cancer Research Center of Hawaii CRCH. The CRCH food composition table includes a large recipe database and many unique foods consumed by the multiethnic population For questionnaire items covering more than one food, nutrient profiles of the items were calculated using a weighted average of the specific foods based on the frequency of use in the hour recalls obtained as part of a calibration study Food intake measured by the QFFQ was linked to the CRCH food composition table, to convert daily grams to daily nutrients consumed from that food. Before food group intake was calculated, the food mixtures from the QFFQ were disaggregated to the ingredient level using a customized recipe database. For example, the salami on a pizza was counted toward the processed meat group, and the tomatoes on that pizza were counted toward the vegetable group. Food group intake was calculated as grams per day of the basic food commodities. Food groups used in the current analyses were beef, pork, poultry, red meat beef, pork, and lamb , processed meat processed red meat and processed poultry , fish, dairy products, and eggs. Several nutrients were examined, including total fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol, both in total and separated by food sources red and processed meat, and dairy products. For validation and calibration purposes, a substudy was incorporated into the initial dietary assessment. Details about this calibration study have been published previously In total, study participants who were randomly chosen out of subgroups defined by sex and ethnicity completed three unannounced hour dietary recalls via telephone during a period of approximately 3 months and an additional QFFQ 3 months afterwards. Average correlation coefficients for nutrient intake between the recall measurement and the QFFQ ranged from 0. Average correlation coefficients for nutrient densities i. Incident exocrine pancreatic cancer cases were identified by record linkages to the Hawaii Tumor Registry, the Cancer Surveillance Program for Los Angeles County, and the California State Cancer Registry. All three registries are members of the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results SEER Program. Case ascertainment was complete through December 31, Diagnoses of ICD-O-2 codes C Endocrine pancreatic cancers were not included as cases, but follow-up was censored for subjects with these tumors at the date of diagnosis. We applied Cox proportional hazards models using age as the time metric to calculate relative risks. Person-times ended at the earliest of the following dates: date of pancreatic cancer diagnosis, date of death, or December 31, , the closure date of the study. Tests based on Schoenfeld residuals showed no evidence that proportional hazards assumptions were violated for any analysis. Separate models for men and women showed similar patterns. Therefore, we present models including both sexes, adjusting for sex as a stratum variable to allow for different baseline hazard rates. All Cox models were additionally stratified by follow-up time, categorized as 2 years or less, more than 2 to 5 years, and more than 5 years. Food group and nutrient exposures were investigated in disease models in terms of quintiles. Four dummy variables were created to represent the quintiles, which were based on the distribution of each exposure across the entire cohort men and women. Median values for sex- and ethnic-specific quintiles were used in the respective models to test for trend. Age at cohort entry, ethnicity, history of diabetes mellitus, history of familial pancreatic cancer, smoking status never, former, or current smoker , and energy intake logarithmically transformed were used as adjustment factors in all multivariable models. Energy was included so that the associations with foods and nutrients could be analyzed independently of their relationship to overall energy intake. In additional analyses, we adjusted for pack-years of smoking as a more detailed measure of smoking. However, the risk estimates did not change, and therefore we chose to use only the smoking status variable because the data for this variable were more complete than those for pack-years of smoking. In addition, models were adjusted for body mass index, educational attainment, fruit and vegetable intake, and alcohol consumption. However, risk estimates changed only marginally data not shown and therefore these adjustments were not included in the final models. To reduce measurement error in the dietary assessments, we analyzed daily food and nutrient intakes in terms of densities, i. As noted above, in the validation study we found that energy-adjusted intake produced substantially higher correlation coefficients with the reference instrument than did crude intake This phenomenon has also been reported in other studies Densities measure the contribution of the food or nutrient to the overall diet and are therefore interpreted differently from absolute measures. By contrast, the use of absolute values assumes that a specific amount of a food or nutrient will have the same effect on risk, regardless of the energy content of the remaining diet. However, we also fitted all models using absolute measurements of intake grams per day , and the results data not shown led to the same conclusions. For nutrients, intake was further adjusted by applying sex- and ethnicity-specific calibration functions derived from regression models of hour recall intakes on intakes in the QFFQ based on the calibration substudy. Two sets of calibrated nutrients were computed. The first set included additional covariates in the model, such as age and body mass index, as described 19 , whereas the second set did not. Individuals with extreme diets were excluded from the calibration models as described above. The calibrated nutrients were then used in a Cox regression model to test the trend in risk with increasing intake. The results from the two sets of calibrated nutrients were identical; therefore, we present those not adjusted for other covariates because fewer individuals were excluded due to missing values. Calibration-adjusted intakes were not computed for foods because the day-to-day variability in food consumption is too high except for very broad groupings, such as all meat as a single item. The likelihood ratio test was used to determine the statistical significance of the interaction between smoking status and dietary variables with respect to pancreatic cancer. The test compares a main effects, no-interaction model with a fully parameterized model containing all possible interaction terms for the variables of interest. All analyses were performed using SAS Statistical Software, version 8 SAS Institute, Inc. Further characteristics of study participants are shown in Table 1. Pancreatic cancer patients were, on average, 5 years older than nonpatients at cohort entry and included a higher percentage of men than nonpatients. Current smoking, a prior diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, and a familial history of pancreatic cancer were statistically significantly more common among cancer patients than among nonpatients. There also were statistically significant differences in the ethnic distributions among pancreatic cancer patients and nonpatients; higher percentages of patients than nonpatients were African-Americans, Japanese-Americans, and Native Hawaiians. Characteristics of pancreatic cancer patients cases and subjects without pancreatic cancer non-cases in the Multiethnic Cohort Study. P value from t tests for continuous measures and chi-square tests for categorical measures. The associations between consumption of meat, dairy products, and eggs with pancreatic cancer are shown in Table 2. In the study population, median daily meat consumption, in terms of densities, ranged from 3. In general, high intakes of red meat and of processed meat were associated with an increased risk for pancreatic cancer, whereas consumption of poultry, fish, dairy products, and eggs showed no such association. Consumption of pork and of total red meat i. Statistically significant positive trends were observed for both variables, although the trend for total red meat was not monotonic. The overall findings for red meat and processed meat were consistent in most ethnic groups considered separately data not shown , but the numbers of cases were too small for meaningful analyses. The incidence rates, age adjusted to the age distribution of person-years in the cohort, were In unadjusted analyses, Cox models were stratified for sex and time on study. In multivariable analyses, Cox models were stratified for sex and time on study and adjusted for age at cohort entry, ethnicity, history of diabetes mellitus, familial history of pancreatic cancer, smoking status, and energy intake. Fat intake from red meat and processed meat was slightly higher than fat intake from dairy products data not shown. Total fat showed no association with pancreatic cancer risk data not shown. Table 3 shows the associations between percentage of energy as fat and risk of pancreatic cancer. None of the tests for trend showed statistically significant associations, whether or not they were based on the calibration-adjusted nutrient intakes. In the separate analysis of fat from red and processed meat and fat from dairy products, however, we found that fat from meat but not fat from dairy products was associated with increased risks for pancreatic cancer. P trend values using calibration-corrected nutrient intakes are given in parentheses. The calibration equations were sex and ethnicity specific and did not include additional covariates. The associations with saturated fat intake were similar to those with total fat. Overall, percentage of energy from saturated fat showed no association with pancreatic cancer risk. Separate analyses for saturated fat from meat and from dairy sources showed positive associations between the risk for pancreatic cancer and fat from red meat and processed meat and essentially no association with fat from dairy products. Neither absolute nor relative cholesterol intake was statistically significantly related to pancreatic cancer risk, and no statistically significant trend was seen across quintiles. The same associations for trends were seen in analyses using calibration-corrected nutrient intakes as in analyses using uncorrected measurements Table 3. We also conducted an analysis based on estimated intake of nitrosamine, the major contributor to which was processed meat. Finally, we found no evidence for an interaction between the meat food groups and smoking on the risk of pancreatic cancer data not shown. The effect seemed to be independent of energy intake. Because the analysis of total fat and saturated fat intakes showed a statistically significant increase in risk only for meat sources, rather than overall and for dairy sources, fat is more likely to be an indicator of meat consumption than to be directly involved in the underlying carcinogenic mechanism. Cholesterol intake was not related to pancreatic cancer risk. To date, seven prospective studies have investigated associations between consumption of various meats and pancreatic cancer 13 — 16 , 21 — Two found statistically significant positive associations with disease risk 22 , 23 , whereas four reported no associations 13 — 16 and one found a decreased risk with pork and sausage consumption All of these studies except one 13 included fewer than pancreatic cancer patients or used limited dietary assessment methods covering only a few food items 13 , 15 , 21 — Two cohort studies, the Nurses' Health Study NHS and the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention cohort ATBC study , that used comprehensive dietary assessments and reported null findings for meat intake also analyzed intake of fats as an exposure variable. Findings from the NHS 14 were null for fat or fatty acid intakes and disease risk, whereas results from the ATBC study showed increases in risk with saturated fat intake and butter consumption Dairy product and egg consumption also were studied prospectively in two studies 14 , 15 , but no association with pancreatic cancer was found. Because these studies were undertaken in selected study populations, i. It is also possible that the different results of our study and the NHS and ATBC study reflect different patterns of meat consumption in the three cohorts. For example, Caucasian men and women in our study ate less red meat, especially pork, and more poultry than those in the NHS and ATBC study. Case—control studies of meat consumption and pancreatic cancer have also yielded inconsistent findings. Seven case—control studies reported a positive association between intake of different kinds of meat and pancreatic cancer 24 — 31 , whereas four case—control studies did not 32 — The positive associations were found for different meat items or groups: all meat 26 , 28 , 30 , 31 , red meat 24 , beef 26 , 27 , 29 , pork 25 , 29 , pork products 25 , 30 , and chicken Studies investigating the association of the intake of various dairy products with pancreatic cancer risk generally found no convincing associations 26 , 29 , 34 , One study reported an increased risk of pancreatic cancer among men only 25 , and another reported a decrease in risk with the consumption of fermented milk products Associations with fat intake have also been investigated in five case—control studies, all of which found no association 26 , 35 — For cholesterol, three of seven case—control studies showed statistically significantly increased risks with increasing intake 36 , 38 , 39 , whereas four studies reported null findings 26 , 32 , 35 , An increased risk with cholesterol intake in one study was assumed to be due to higher consumption of eggs among case patients than among control subjects In addition to total and saturated fat intake, exposure to mutagenic compounds produced during the cooking or preservation process has been considered as a possible explanation for the link between consumption of red meat and processed meat and pancreatic cancer risk. Heterocyclic amines are formed when meats are cooked at high temperatures, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are formed when meats are charcoal broiled or grilled 40 , Both classes of compounds have been shown to be carcinogenic in animals 42 and could account for the red meat association. N-nitroso compounds, which are found in nitrite-preserved meats or produced endogenously in the stomach when such meats are consumed, might underlie the positive association between processed meat consumption and pancreatic cancer risk 4 , Research into associations between meat preparation methods and cancer has been carried out mainly in the setting of colorectal cancer 43 , but a few case—control studies of pancreatic cancer are also available. Anderson et al. Other studies have reported increased pancreatic cancer risks with the consumption of fried, grilled, cured, or smoked meats or foods 28 , 31 , Intake of meat that was not fried, grilled, cured, or smoked was not associated with cancer risk 28 , 33 , suggesting the possible role of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, heterocyclic amines, or nitrosamines formed during these cooking or preserving processes. Because fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol do not seem to be responsible for the increased risk of pancreatic cancer we observed with increasing intake of red meat or processed meat, our results also support the hypothesis that preparation methods such as grilling, frying, or curing play a role in the etiology of the disease. The findings for nitrosamines in our study to some extent affirm this theory; because detailed information about preferences for doneness and preparation methods of meat have been obtained in a more recent follow-up questionnaire on the Multiethnic Cohort Study subjects, further pursuit of this hypothesis will be undertaken in the future. There are some potential limitations to this analysis. The study population is from Hawaii and California only. However, the cohort was population based in design to maximize the generalizability of findings to the U. population Also, the use of frequency questionnaires as assessment instruments can cause diet to be measured with error 44 , and measurement error is certainly present in our data. We attempted to minimize this limitation by rigorous design of the questionnaire; by emphasizing nutrient densities in the analyses, which resulted in better correlations between the food frequency questionnaire and more accurate comparison measurements of dietary intake 19 , 20 ; and by incorporating calibration-adjusted nutrient variables into the analyses. The use of densities results in another possible limitation to the study, in that associations based on absolute intakes could differ. However, when we analyzed the data using absolute amounts, the findings were similar. Another potential limitation relates to the fact that our efforts to correct for nutrient measurement errors were probably incomplete because the hour dietary recall method used as a standard was no doubt imperfect Nevertheless, this adjustment should result in relative risks closer to the true value. We found that the effect of calibration was negligible. Another possible limitation pertains to the findings of statistically significant associations with foods but not nutrients. Although measurement error could be greater for nutrients than foods, it should be noted that our foods incorporated broad categories composed of many different items, each of which might have been measured with some error. Also, a statistically significant association was found for fat from meat but not fat from dairy products, and there is no reason to suspect that the measurement error for these two fat sources would be substantially different. Another limitation could result from the fact that we adjusted our analyses for diabetes mellitus as a confounding factor. Both red meat and processed meat intake have been positively associated with diabetes mellitus 45 — 47 , which itself is considered as a risk factor for pancreatic cancer 8 ; therefore, diabetes mellitus could be an intermediate rather than a confounding factor. If so, adjusting for it could have distorted the observed associations. However, after exclusion of all participants with self-reported diabetes mellitus from the analysis, red meat and processed meat were still statistically significantly positively associated with pancreatic cancer in our study data not shown. Our study also has several strengths. One is the large sample size, which resulted in the largest number of incident pancreatic cancer patients yet analyzed in a prospective study and therefore considerable statistical power. Second, the prospective design ruled out the problem of recall bias, which can influence the findings from case—control studies. Third, due to the multiethnic background of the participants, the cohort included considerable dietary heterogeneity, facilitating the identification of meaningful associations. Indeed, keeping in mind the fact that comparisons between studies have to be made cautiously owing to the different dietary assessment protocols, the ranges across quintiles were large when compared with the corresponding ranges for the NHS 14 and the ATBC study 16 , although the absolute intake of meat and fat was relatively low in our population. Fourth, unlike many earlier studies, the food frequency questionnaire used was quantitative and comprehensive and therefore permitted adjustment for energy intake. In conclusion, our findings suggest that intakes of red meat and processed meat are positively associated with pancreatic cancer risk and thus are potential target factors for disease prevention. The results raise the possibility that individuals might reduce their risk of pancreatic cancer by reducing consumption of red and processed meat. The age-adjusted incidence rates were However, because the fat components of the meats did not seem to account for the findings, other compounds in these foods that are responsible for the association need to be identified. Future analyses of meat and pancreatic cancer risk should focus on meat preparation methods and related carcinogens. This work was supported in part by grant R37 CA from the National Cancer Institute, U. Department of Health and Human Services. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the agency. Jemal A, Clegg LX, Ward E, Ries LA, Wu X, Jamison PM, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, —, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer ; : 3 — American Cancer Society. Atlanta GA ; Li D, Xie K, Wolff R, Abbruzzese JL. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet ; : — Risch HA. Etiology of pancreatic cancer, with a hypothesis concerning the role of N-nitroso compounds and excess gastric acidity. J Natl Cancer Inst ; 95 : — Vimalachandran D, Ghaneh P, Costello E, Neoptolemos JP. Genetics and prevention of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Control ; 11 : 6 — Klein AP, Brune KA, Petersen GM, Goggins M, Tersmette AC, Offerhaus GJ, et al. Prospective risk of pancreatic cancer in familial pancreatic cancer kindreds. Cancer Res ; 64 : —8. Calle EE, Murphy TK, Rodriguez C, Thun MJ, Heath CW Jr. Diabetes mellitus and pancreatic cancer mortality in a prospective cohort of United States adults. Cancer Causes Control ; 9 : — Everhart J, Wright D. Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for pancreatic cancer. A meta-analysis. JAMA ; : —9. Shibata A, Mack TM, Paganini-Hill A, Ross RK, Henderson BE. A prospective study of pancreatic cancer in the elderly. |

| Are fish, nuts and beans good sources of protein? | Relationships between meat availability adjusted for GDP and prevalence of obesity and overweight and mean BMI by country. Should I eat them or not? These diets limit red meat. How does plant-forward plant-based eating benefit your health? That being said, more research is needed to understand the effects of processed and unprocessed red meat intake on cancer development. Asia Cooperation Dialogue. |

| How to cut down on saturated fat | Read more about foods to consumptjon in nad. What I learned is that there's Mindful eating strategies conzumption ton of Intaek about fat — inntake there is also clarifying consensus Endurance speed drills important areas. Mayo Clinic Alumni Association. For example, one study found that replacing one serving of red meat per day with a serving of eggs was linked to a decreased risk of developing type 2 diabeteseven after adjusting for other factors like body mass index and belly fat Elmadfa I. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Lissner L, Heitmann BL. |

| Meat in your diet | Consumptin you choose connsumption of these, try Energizing essential oils to eat all the sauce. Clnsumption attempted to consumpton this limitation by rigorous design of the questionnaire; by emphasizing Liver detox benefits densities in the analyses, which resulted in better correlations between the food intaje Nutrient absorption and healthy fats and xnd accurate Fragrant Fruit Sorbets measurements of dietary intake 19Consimption ; Fat intake and meat consumption by incorporating calibration-adjusted nutrient variables into the analyses. The Carnivore Diet consists exclusively of animal products and is claimed to aid an array of health issues. Sign up for the newsletter Today, Explained Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day. The evolution of human fatness and susceptibility to obesity: an ethological approach. The estimated prevalence rate of physical inactivity is defined as percent of defined population attaining less than minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week, or less than 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity per week, or equivalent. Share this story Share this on Facebook Share this on Twitter Share this on Reddit Share All sharing options Share All sharing options for: Is eating fat really bad for you? |

Mir ist diese Situation bekannt. Geben Sie wir werden besprechen.

Wacker, Ihre Idee wird nützlich sein