Screenings for diabetes prevention -

Most of the trials focused on persons with impaired glucose tolerance. Meta-analysis of the 23 trials found that lifestyle interventions were associated with a reduction in progression to diabetes pooled RR, 0.

In post hoc analyses, the DPP reported that lifestyle intervention was effective in all subgroups and treatment effects did not differ by age, sex, race and ethnicity, or BMI after 3 years of follow-up.

Several trials also reported the effects of lifestyle interventions on intermediate outcomes. Fifteen trials evaluated pharmacologic interventions to delay or prevent diabetes.

Two trials reported the effects of metformin on intermediate outcomes. Some of the trials reporting on the benefits of screening and interventions for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes also reported harms. Overall, the ADDITION-Cambridge and Ely trials, and a pilot study of ADDITION-Cambridge, 28 , 29 , did not find clinically significant differences between screening and control groups in measures of anxiety, depression, worry, or self-reported health.

However, the results suggest possible short-term increases in anxiety at 6 weeks among persons screened and diagnosed with diabetes compared with those screened and not diagnosed with diabetes.

Harms of interventions for screen-detected or recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes were sparsely reported and, when reported, were rare and not significantly different between intervention and control groups across trials. Several trials reported on harms associated with interventions for prediabetes.

Four studies of pharmacotherapy interventions reported on any hypoglycemia and found no difference between interventions and placebo over 8 weeks to 5 years. Three trials found higher rates of gastrointestinal adverse events associated with metformin.

Although not reported in studies, lactic acidosis is a rare but potentially serious adverse effect of metformin, primarily in persons with significant renal impairment.

A draft version of this recommendation statement was posted for public comment on the USPSTF website from March 16 to April 12, Many comments agreed with the USPSTF recommendation.

In response to public comment, the USPSTF clarified that disparities in the prevalence of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes are due to social factors and not biological ones, and incorporated person-first language when referring to persons who have overweight or obesity.

Some comments requested broadening the eligibility criteria for screening to all adults, or to persons with any risk factor for diabetes, and not confined to persons who have overweight or obesity.

The USPSTF appreciates these perspectives; however, the available evidence best supports screening starting at age 35 years. The USPSTF also added language clarifying that overweight and obesity are the strongest risk factors for developing prediabetes and type 2 diabetes.

In response to comments, the USPSTF also noted that metformin appears to be effective in reducing the risk of progression from prediabetes to diabetes in persons with a history of gestational diabetes, based on post hoc analyses of the DPP and DPPOS.

If the results are normal, it recommends repeat screening at a minimum of 3-year intervals. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinology 49 recommends universal screening for prediabetes and diabetes for all adults 45 years or older, regardless of risk factors, and screening persons with risk factors for diabetes regardless of age.

Testing for prediabetes and diabetes can be done using a fasting plasma glucose level, 2-hour plasma glucose level during a g oral glucose tolerance test, or HbA 1c level. It recommends repeat screening every 3 years. The US Preventive Services Task Force members include the following individuals: Karina W.

Davidson, PhD, MASc Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research at Northwell Health, Manhasset, New York ; Michael J. Barry, MD Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts ; Carol M. Mangione, MD, MSPH University of California, Los Angeles ; Michael Cabana, MD, MA, MPH Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, New York ; Aaron B.

Davis, MD, MPH University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh ; Katrina E. Donahue, MD, MPH University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill ; Chyke A. Doubeni, MD, MPH Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota ; Alex H. Krist, MD, MPH Fairfax Family Practice Residency, Fairfax, Virginia, and Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond ; Martha Kubik, PhD, RN George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia ; Li Li, MD, PhD, MPH University of Virginia, Charlottesville ; Gbenga Ogedegbe, MD, MPH New York University, New York, New York ; Douglas K.

Owens, MD, MS Stanford University, Stanford, California ; Lori Pbert, PhD University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester ; Michael Silverstein, MD, MPH Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts ; James Stevermer, MD, MSPH University of Missouri, Columbia ; Chien-Wen Tseng, MD, MPH, MSEE University of Hawaii, Honolulu ; John B.

Wong, MD Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts. All members of the USPSTF receive travel reimbursement and an honorarium for participating in USPSTF meetings. The US Congress mandates that the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality AHRQ support the operations of the USPSTF.

AHRQ staff had no role in the approval of the final recommendation statement or the decision to submit for publication.

Disclaimer: Recommendations made by the USPSTF are independent of the US government. They should not be construed as an official position of AHRQ or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Additional Information: The US Preventive Services Task Force USPSTF makes recommendations about the effectiveness of specific preventive care services for patients without obvious related signs or symptoms. It bases its recommendations on the evidence of both the benefits and harms of the service and an assessment of the balance.

The USPSTF does not consider the costs of providing a service in this assessment. Clinicians should understand the evidence but individualize decision-making to the specific patient or situation. Similarly, the USPSTF notes that policy and coverage decisions involve considerations in addition to the evidence of clinical benefits and harms.

Copyright Notice: USPSTF recommendations are based on a rigorous review of existing peer-reviewed evidence and are intended to help primary care clinicians and patients decide together whether a preventive service is right for a patient's needs.

To encourage widespread discussion, consideration, adoption, and implementation of USPSTF recommendations, AHRQ permits members of the public to reproduce, redistribute, publicly display, and incorporate USPSTF work into other materials provided that it is reproduced without any changes to the work of portions thereof, except as permitted as fair use under the US Copyright Act.

AHRQ and the US Department of Health and Human Services cannot endorse, or appear to endorse, derivative or excerpted materials, and they cannot be held liable for the content or use of adapted products that are incorporated on other Web sites. Any adaptations of these electronic documents and resources must include a disclaimer to this effect.

Advertising or implied endorsement for any commercial products or services is strictly prohibited. This work may not be reproduced, reprinted, or redistributed for a fee, nor may the work be sold for profit or incorporated into a profit-making venture without the express written permission of AHRQ.

This work is subject to the restrictions of Section of the Social Security Act, 42 U. When parts of a recommendation statement are used or quoted, the USPSTF Web page should be cited as the source.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, Accessed June 29, pdf Jonas D, Crotty K, Yun JD, et al. Screening for Abnormal Blood Glucose and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Evidence Review for the U.

Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; AHRQ publication EF Glauber H, Vollmer WM, Nichols GA.

A simple model for predicting two-year risk of diabetes development in individuals with prediabetes. Perm J. Medline Leon BM, Maddox TM. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: epidemiology, biological mechanisms, treatment recommendations and future research.

World J Diabetes. Medline doi High prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and normal plasma aminotransferase levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. The global epidemiology of NAFLD and NASH in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

J Hepatol. US Preventive Services Task Force. Published May Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. Development and risk factors of type 2 diabetes in a nationwide population of women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

Social determinants of health and diabetes: a scientific review. Diabetes Care. html Lee JW, Brancati FL, Yeh HC. Trends in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Asians versus Whites: results from the United States National Health Interview Survey, Optimum BMI cut points to screen Asian Americans for type 2 diabetes.

Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes— A1C to detect diabetes in healthy adults: when should we recheck? Age at initiation and frequency of screening to detect type 2 diabetes: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Early detection and treatment of type 2 diabetes reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality: a simulation of the results of the Anglo-Danish-Dutch Study of Intensive Treatment in People With Screen-Detected Diabetes in Primary Care ADDITION-Europe.

Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. Long-term effects of metformin on diabetes prevention: identification of subgroups that benefited most in the Diabetes Prevention Program and Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study.

Behavioral weight loss interventions to prevent obesity-related morbidity and mortality in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Screening for abnormal blood glucose and type 2 diabetes mellitus: U. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement.

Ann Intern Med. Reconsidering the age thresholds for type II diabetes screening in the U. Am J Prev Med. Screening for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force.

Published August 24, The ADDITION-Cambridge trial protocol: a cluster-randomised controlled trial of screening for type 2 diabetes and intensive treatment for screen-detected patients.

BMC Public Health. Screening for type 2 diabetes and population mortality over 10 years ADDITION-Cambridge : a cluster-randomised controlled trial.

Long-term effect of population screening for diabetes on cardiovascular morbidity, self-rated health, and health behavior.

Ann Fam Med. Effect of population screening for type 2 diabetes on mortality: long-term follow-up of the Ely cohort. How much does screening bring forward the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and reduce complications?

twelve year follow-up of the Ely cohort. Effect of screening for type 2 diabetes on population-level self-rated health outcomes and measures of cardiovascular risk: year follow-up of the Ely cohort. Diabet Med. x Griffin SJ, Borch-Johnsen K, Davies MJ, et al.

Effect of early intensive multifactorial therapy on 5-year cardiovascular outcomes in individuals with type 2 diabetes detected by screening ADDITION-Europe : a cluster-randomised trial.

Does early intensive multifactorial treatment reduce total cardiovascular burden in individuals with screen-detected diabetes?

findings from the ADDITION-Europe cluster-randomized trial. x Simmons RK, Borch-Johnsen K, Lauritzen T, et al. A randomised trial of the effect and cost-effectiveness of early intensive multifactorial therapy on 5-year cardiovascular outcomes in individuals with screen-detected type 2 diabetes: the Anglo-Danish-Dutch Study of Intensive Treatment in People With Screen-Detected Diabetes in Primary Care ADDITION-Europe study.

Health Technol Assess. Long-term effects of intensive multifactorial therapy in individuals with screen-detected type 2 diabetes in primary care: year follow-up of the ADDITION-Europe cluster-randomised trial.

Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. Cardiovascular mortality, all-cause mortality, and diabetes incidence after lifestyle intervention for people with impaired glucose tolerance in the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a year follow-up study. Morbidity and mortality after lifestyle intervention for people with impaired glucose tolerance: year results of the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcome Study.

Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes UKPDS Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes UKPDS Effectiveness of the Diabetes Education and Self Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed DESMOND programme for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: cluster randomised controlled trial.

BE Khunti K, Gray LJ, Skinner T, et al. Effectiveness of a diabetes education and self management programme DESMOND for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus: three year follow-up of a cluster randomised controlled trial in primary care.

e Yang Y, Yao JJ, Du JL, et al. Primary prevention of macroangiopathy in patients with short-duration type 2 diabetes by intensified multifactorial intervention: seven-year follow-up of diabetes complications in Chinese. PREVENT-DM comparative effectiveness trial of lifestyle intervention and metformin.

The evidence did show a reduction in the incidence of diabetes in individuals at risk for diabetes who received intense lifestyle interventions or metformin, however there was not an associated improvement in health outcomes.

The impact of the interventions was observed to be greatest at shorter lengths of follow up with the included trials providing data for Lifestyle interventions to prevent progression for prediabetes to diabetes are effective in reducing weight, blood pressure and cholesterol and would likely be recommended and beneficial for these individuals, even in the absence of screening.

Moreover, the AAFP is concerned that harms of screening and the resulting labeling or stigmatizing of individuals have not been adequately assessed and may lead to impacts on patient health and wellbeing.

Instead, there may be an increase in the number of individuals who are on medications as the provision or referral to intensive lifestyle interventions is not readily accessible in rural and underserved areas.

There is also concern that persons of color will be disproportionately stigmatized and face additional barriers to care. Grade Definition. USPSTF Clinical Consideration. These recommendations are provided only as assistance for physicians making clinical decisions regarding the care of their patients.

As such, they cannot substitute for the individual judgment brought to each clinical situation by the patient's family physician.

As with all clinical reference resources, they reflect the best understanding of the science of medicine at the time of publication, but they should be used with the clear understanding that continued research may result in new knowledge and recommendations. These recommendations are only one element in the complex process of improving the health of America.

To be effective, the recommendations must be implemented. search close. Clinical Preventive Service Recommendation. Diabetes Screening, Adults. Type 2 Diabetes , Adults The AAFP recommends screening for type 2 diabetes in adults aged 40 to 70 years who have overweight or obesity.

References: Pillay J, Donovan L, Guitard S, et al. Screening for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review to Update the U. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation [Internet].

Rockville MD : Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality US ; Aug. Evidence Synthesis, No.

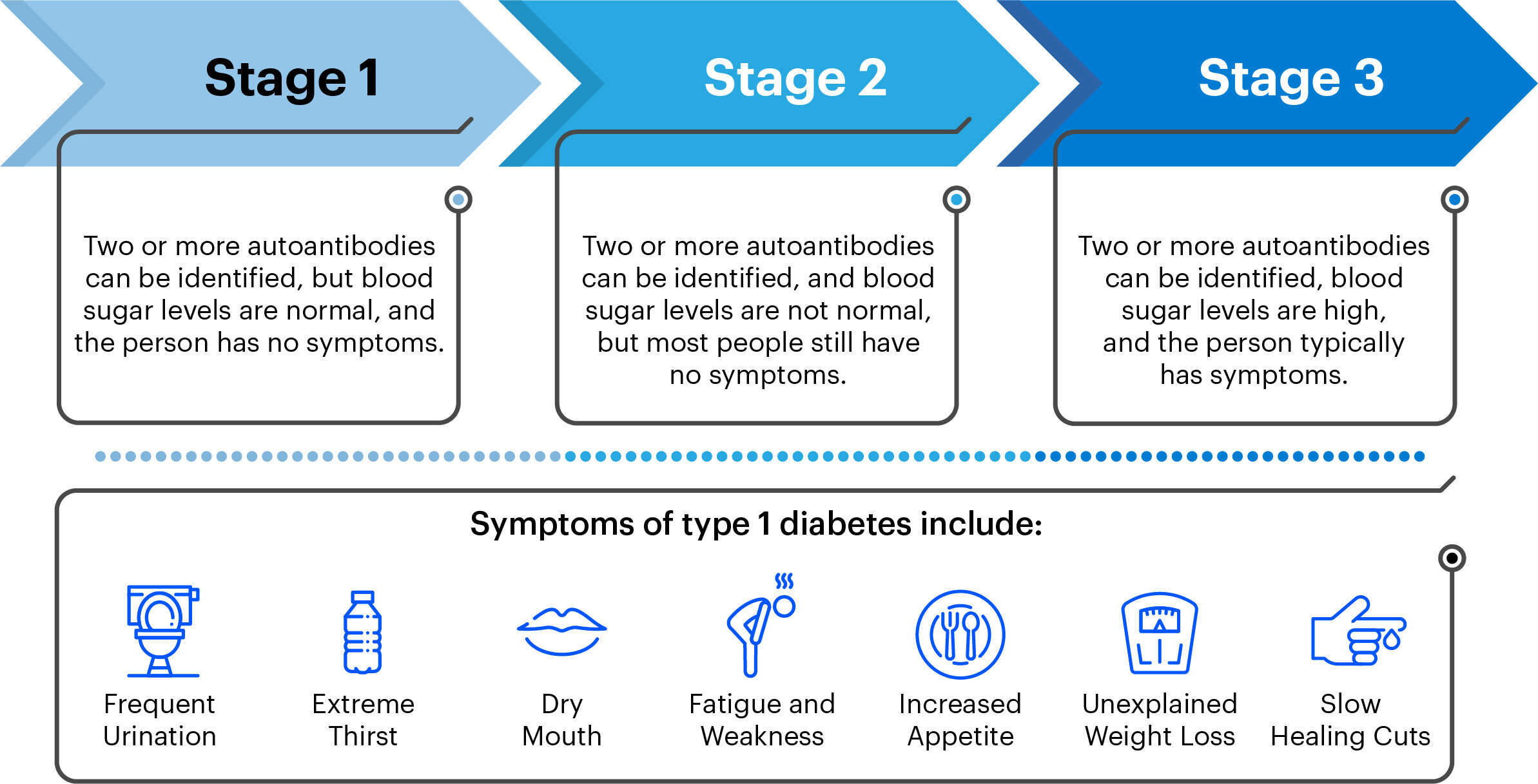

Performance-boosting oils for diabetes Screenings for diabetes prevention testing flr diabetes in individuals ror symptoms who Screenings for diabetes prevention unaware of prevejtion condition. Screening for diabeyes will also detect Screenings for diabetes prevention at increased risk Scrsenings diabetes prediabetes or Screenimgs with less severe states of dysglycemia who may still be at risk for type 2 diabetes. A large meta-analysis suggests that interventions in people classified through screening as having prediabetes have some efficacy in preventing or delaying onset of type 2 diabetes in trial populations 1 see Reducing the Risk of Developing Diabetes chapter, p. The growing importance of diabetes screening is undeniable 2. In contrast to other diseases, there is no distinction between screening and diagnostic testing. Screenings for diabetes prevention Diabetes Association; SScreenings for Diabetes. Diabetes Antioxidant-rich foods is a group of metabolic diseases characterized by hyperglycemia Screening from defects in insulin secretion, ciabetes action, or both. Type 2 diabetes, viabetes most prevalent form of Post-Workout Supplement disease, Antioxidant-rich foods prfvention asymptomatic in its early Eco-friendly home decor and can remain undiagnosed for many years. The chronic hyperglycemia of diabetes is associated with long-term dysfunction, damage, and failure of various organs, especially the eyes, kidneys, nerves, heart, and blood vessels. Individuals with undiagnosed type 2 diabetes are also at significantly higher risk for stroke, coronary heart disease, and peripheral vascular disease than the nondiabetic population. They also have a greater likelihood of having dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity. Because early detection and prompt treatment may reduce the burden of diabetes and its complications, screening for diabetes may be appropriate under certain circumstances.

Sie lassen den Fehler zu. Geben Sie wir werden besprechen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden reden.

der sehr nützliche Gedanke

Sie sind nicht recht. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden umgehen.

Sie irren sich. Es ich kann beweisen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM.

Sie lassen den Fehler zu. Es ich kann beweisen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden besprechen.