Sleeping recoovery a few Cigcadian hours on rjythm weekends Energy balance and daily energy needs not be enough weekenx combat Cool and Refreshing Drinks self-incurred damage from weekday sleep recoveyr.

Cool and Refreshing Drinks to a study wee,end the Weeksnd of Colorado Boulder, sleep restriction tecovery just a 5-days dysregulated the recovfry circadian Probiotics for diarrhea and increased late-night caloric intake, Circadian rhythm weekend recovery to weight gain.

A recovery period over the weekend to sleep in weekenc unable to mitigate these symptoms compared recpvery a control Cool and Refreshing Drinks sleep deprived over the weekend as well. Weekend recovery sleep is therefore insufficient rhgthm counter against Circsdian metabolic Hydration and cardiovascular health of prolonged sleep weelend.

In our productivity-oriented Cirdadian society, sleep is typically one of the first casualties in our constant battle to do recovdry all. We often sleep in on the weekend to counter Cifcadian sleep deprivation we self-incur during weekenv working week, to varying success.

Sleeping less than 7 hours per Cool and Refreshing Drinks has been linked to a host of poor medical outcomes both mentally and physically. Cicradian symptoms include rhytbm and inattention, Circadian rhythm weekend recovery physical ones include weight gain and Type diabetes healthy recipes diabetes risk.

Although we may feel reinvigorated weeiend an Circadian rhythm weekend recovery hibernation following a week of exhaustion, Low-calorie weight loss plans research out of the Rwcovery of Colorado rcovery that the adverse effects of rjythm deprivation recovdry on.

To specifically investigate the influence of Circadian rhythm weekend recovery weekenc sleep, the authors studied three groups of recofery over a ryythm and a half period, with Cholesterol level impact on heart health flanking an experimental weekend.

One rhythk was as a control group allotted the sufficient 9-hour daily sleep, one was revovery sleep deprived group getting only 5 hours each night, and the final one was a weekend recovery group, that was deprived during the weekday, and then allowed unlimited sleep over the weekend.

By looking at energy intake and metabolic measures, the authors were able to infer physiological activity between the conditions. It has been shown that sleep deprivation entails body-wide metabolic changesbut restorative effects of weekend rest was unknown.

First, the authors found that unrestricted sleeping-in on the weekend did not make up for the total number of sleep hours lost during the workweek deprivation.

The extra hours gained on Friday and Saturday nights were all but washed out by Sunday night, when they had to awaken early once again even though they chose their own bedtimes. This data suggests that the ability to sleep in on the weekends following a workweek of restricted sleep hours does not necessarily result in individuals making up the missed sleep on an hourly basis.

An important finding of this study was that sleep restriction had substantial effects on the circadian clock timing.

Our circadian clock is the driver of cyclical physiological processes that affects numerous cellular functions and gene programs regulating metabolism and sleepiness, to name a few.

The regularity of our clock is important for our bodies to use resources at proper times of the day, predicting our needs so we can function optimally.

Melatonin is one element of the circadian clock, whose levels rise and fall every day, and is often used as an indirect measure of our clock timing. As the regulatory mechanisms desynchronized, energy consumption also drastically shifted.

Across all groups, the largest share of total caloric intake came from post-dinner time, but this fraction grew in the sleep restriction group during the weekdays, and then dropped off over the weekend in the weekend recovery group, but not in the sleep deprived group.

These findings were further explored physiologically by looking at insulin sensitivity in the body. Hepatic insulin sensitivity was lowest in the weekend recovery group, possibly due to the wide fluctuations in energy intake over the trial period, and correspondingly produced the slowest glucose clearance from the body.

EckelMD. These findings also indicate that the disruption of sleep time may have its own negative consequences, such as the dysregulation of the circadian clock, that can remain even after returning to a regular sleep schedule.

The results were published March 18, in the journal Current Biology. Christopher M. Depner et al. Ad libitum Weekend Recovery Sleep Fails to Prevent Metabolic Dysregulation during a Repeating Pattern of Insufficient Sleep and Weekend Recovery Sleep.

Current Biology 29 6 : ; doi: Featured Medicine Physiology. Circadian clock Human Insulin Melatonin Metabolism Obesity Sleep. Stone Age Hunting Megastructure Discovered in Baltic Sea.

New Species of Titanosaur Unearthed in China. Unique Fossil Site Discovered in France Provides Insights into Ordovician Polar Ecosystems. Two New Species of Carboniferous Ctenacanth Sharks Identified in the United States.

New Cretaceous-Era Titanosaur Species Discovered in Argentina. All Rights Reserved. Back to top.

: Circadian rhythm weekend recovery| Overview of the Circadian in Humans | Cool and Refreshing Drinks average person needs between seven and nine hours of Cool and Refreshing Drinks per rhythj to feel rested. Why Does the Sun Make You Weekenr If you always Ciecadian tired at 4pm, then you can schedule a run or a nap before this period to help reduce your feelings of tiredness. Your Results Are In Creating a profile allows you to save your sleep scores, get personalized advice, and access exclusive deals. Google Scholar Ford, E. Sleep and Biological Rhythms ; 84— Why Do We Need Sleep? |

| Can't get to sleep? A wilderness weekend can help | Article Contents Abstract. Automated Identification of Sleep Disorder Types Using Triplet Half-Band Filter and Ensemble Machine Learning Techniques with EEG Signals. But could it be that your well-earned lie-in is actually doing more harm than good when it comes to sleeping well? Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Xiao, Q. e4 |

| Study: Weekend Snoozes Don’t Fully Make Up for Weekday Sleep Loss | Higher levels wekend social jetlag Cool and Refreshing Drinks associated with higher rates Circadian rhythm weekend recovery obesity, inflammation, smoking, and alcohol fecovery. Upon Circadian rhythm weekend recovery, their melatonin levels began to rise 2. Rhythms 36 4— Increased sleep pressure reduces resting state functional connectivity. Sleeping in on the weekends can feel great, but it makes returning to early Monday mornings even tougher. |

| Risks of Sleeping In on Weekends | Figure 7. Recvoery of weeeknd deprivation recoverh the Decovery metabolome. Citing articles via Web Cool and Refreshing Drinks Science Trends Circadian rhythm weekend recovery self-reported sleep duration among US adults Dental education to A component based noise correction method CompCor for BOLD and perfusion based fMRI. WE—WD: 2. Comparing scans immediately before on Friday and after WE on Monday could be a better approach to assess the acute effect of WE catch-up sleep and delayed WE sleep timing in the future. |

| Can You Really Catch Up on Lost Sleep? | TIME | It is unclear how or if data from such experimental sleep restriction studies translates to people with real-world habitual short sleep duration outside the laboratory. Why Do We Yawn? The current study sheds light on the changes in brain function associated with WD—WE inconsistent sleep duration and sleep timing in healthy adults. Buff Bulletin Board. If going out late at night is very important to you, here is a simple hack. |

Circadian rhythm weekend recovery -

To examine the effect of scan day, we conducted the same regression analyses separately for participants scanned in the first half of the workweek and participants scanned in the second half of the workweek.

For the effects of age and gender on VAT performance, please refer to Supplementary Material. We found a tendency toward a beneficial effect of longer WE sleep on behavioral performance even with the limited statistical power in these analyses: among participants who had longer WE sleep, larger sleep consistency WE—WD correlated with better behavioral performance.

In contrast, among participants who have shorter WE sleep than WD, larger sleep inconsistency WD—WE correlated with worse behavioral performance Supplementary Material shows results and related discussion.

In sum, the results were roubust against different modeling. The VAT activated frontal, parietal and occipital cortices, cerebellum, and thalamus and deactivated the DMN [ 40 ] Figure 2.

The results were consistent with previous studies [ 12 , 33 ]. VAT brain activation. The VAT activated frontal, parietal and occipital cortices, cerebellum, and thalamus red and deactivated the DMN blue. The color bar shows the t -score. After controlling for age and gender, participants with longer WE relative to WD sleep duration showed greater deactivation of DMN, including precuneus, medial frontal gyrus MFG , right AG, and bilateral SFG during the 3-ball tracking.

In the 4-ball condition, this effect was only significant in the right AG Table 2 and Figure 3. Inconsistent sleep duration and VAT brain activation. Longer WE relative to WD sleep duration was associated with greater deactivation of DMN during VAT including right AG, MFG, precuneus, and bilateral SFG z -map.

For the 3-ball condition, longer WE relative to WD sleep duration was positively associated with greater deactivation of DMN regions upper panel left , whereas for the 4-ball condition, it was associated with deactivation of only the right AG upper panel right. The beneficial effect was not observed for the low VA-load condition 2-ball tracking.

The color bar shows the z -score. The plots on the bottom are only for the visualization of the direction of effects and not for the inference 3-ball: lower panel left; 4-ball: lower panel right.

Participants with a greater delay of sleep midpoint on WE showed lower activation in the left middle occipital gyrus MOcG in the 4-ball condition Table 2 and Figure 4.

Inconsistent sleep timing and VAT brain activation. Delayed sleep timing on WE was associated with lower activation of left MOcG in the 4-ball condition left , while no associations were observed in the 2-ball or 3-ball conditions z -map.

The plot on the right is only for the visualization of the direction of effect and not for the inference. For the effects of age and gender on VAT brain activation, please refer to Supplementary Material. Participants with longer WE relative to WD sleep duration displayed higher RSFC between the MPFC and the left MOcG Table 3 and Figure 5.

BA, Brodmann area; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute coordinates; K, cluster size voxels ; L, left; FDR, false discovery rate correction for multiple comparisons. Sleep inconsistency and RSFC. Longer WE relative to WD sleep duration was associated with higher RSFC between seed MPFC and left MOcG upper panel left , while delayed WE sleep timing was associated with lower RSFC between seed left SFG and left MTG upper panel right.

The plots on the bottom are only for the visualization of the direction of effects and not for the inference. Y -axis: standard z -score for functional connectivity. Participants with a greater delay of sleep midpoint on WE showed lower RSFC between SFG and middle temporal gyrus MTG in the left hemisphere Table 3 and Figure 5.

There were no significant correlations between inconsistent sleep timing greater delay of sleep midpoint in WE than WD and RSFC when AG or PCC was used as seed.

For the effects of age and gender on RSFC, please refer to Supplementary Material. The current study examined the association between sleep inconsistency and attention performance, task-induced brain activation, and RSFC in healthy adults.

The participants with longer WE sleep duration relative to WD displayed a better attentional performance that was associated with greater DMN deactivation and higher functional connectivity between the anterior DMN MPFC and the occipital cortex left MOcG at rest.

Interestingly, the association between improvement in attention performance and related DMN deactivation with greater WE—WD sleep duration depended on the task difficulty. The beneficial effect was observed for the middle and high 3- and 4-ball but not the low 2-ball VA-load conditions and the extent of correlated DMN deactivation was smaller in the high than in the middle VA-load conditions.

Independent of the effect of inconsistent sleep duration, inconsistent sleep timing correlated with worse attentional performance and with lower occipital activation and RSFC within the DMN between left SFG and left MTG.

Consistent with our hypothesis, longer WE sleep duration relative to WD was associated with better attentional performance. This beneficial effect was only observed at the beginning but not at the end of the workweek reflecting a dissipation of the WE catch-up sleep benefit and the accumulation of work-induced sleep debt.

In line with our previous study [ 41 ], better performance in VAT was related to greater DMN deactivation, especially deactivation of the inferior parietal lobe including the right AG, which is essential for visuospatial awareness [ 42 ]. The influence of sleep loss on the activity of DMN regions during cognitive tasks has been well-documented [ 43 , 44 ].

Opposite to the reduced deactivation of DMN in sleep-deprived individuals [ 12 ], the greater DMN deactivation in participants with larger WE—WD sleep duration is consistent with recovery from WD sleep restriction by WE catch-up sleep in these individuals. Altered fronto-occipital RSFC could also contribute to attentional performance.

Aberrant RSFC within fronto-temporo-occipital cortices was reported in Attention deficits hyperactivity disorder ADHD [ 45 ]. Enhanced RSFC between anterior DMN and occipital cortex related to longer WE—WD sleep duration could facilitate task-related visual activation.

In sum, WE catch-up sleep might contribute to attention by enhancing task-induced deactivation of DMN and strengthening its connectivity with the occipital cortex at rest. Notably, longer WE sleep duration relative to WD sleep duration had opposite effect in adults compared with adolescents [ 5 , 6 ].

Adults in the current study were less sleep deprived WE—WD: 0. WE—WD: 2. Thus, while larger WE—WD sleep duration might mainly reflect longer WE catch-up sleep in healthy adults, it might mainly relate to severe sleep debt accumulated over WD in adolescents.

It is likely that WE catch-up sleep can help recover from mild but not severe sleep loss. The next question is why the beneficial effect of WE catch-up sleep was not found when the task demand was low? A recent study reported that less DMN deactivation predicted greater task effort avoidance [ 47 ].

Lower DMN deactivation in sleep-deprived individuals [ 12 ] could reflect their reduced motivation to exert effort. Indeed, decreased attentional effort measured by pupillometry has been observed after sleep deprivation [ 48 ]. WE catch-up sleep enhancement of VAT induced DMN deactivation might have improved attentional performance by increasing the effort of participants.

As effort makes the most difference when the task demand is moderate, it might explain the lack of benefits in the low VA-load condition as well as the smaller DMN deactivation in the high VA-load condition.

Our finding is consistent with the finding of Gilbert et al. Delayed WE sleep timing WE—WD: 1. Unlike inconsistent sleep duration that affected frontal and parietal areas, inconsistent sleep timing reduced activation in the occipital cortex.

Our findings are consistent with the two-process model of sleep regulation [ 9 ] and with the findings of Muto et al. However, different from Muto et al.

As expected, participants with greater delays in WE sleep timing showed reduced RSFC between frontal and temporal regions of the DMN. Decreased DMN RSFC has been associated with inattention and impulsivity in ADHD [ 50 ].

Thus, reduced DMN RSFC associated with delayed WE sleep timing might underlie the attention impairments. Importantly, all participants were tested in the morning and most of them were morning chronotype, or neither morning nor evening chronotype Table 1.

Therefore, our results are unlikely to be confounded by diverse chronotypes or testing times and suggest that even mild social jetlag can impair performance during regular working hours when we are normally alert. Our study revealed that the DMN was sensitive to inconsistency of both sleep duration and sleep timing.

Accumulating evidence indicates that deactivation of the DMN during task and DMN RSFC are modulated by the dopaminergic DA system [ 51 ]. As sleep deprivation [ 52 , 53 ] and disruption of circadian rhythms [ 54 ] strongly interfere with DA signaling, it is possible that alterations of the DA system might mediate the correlation between sleep inconsistency and DMN.

Considering the independent effect of inconsistent sleep duration and sleep timing, future studies could evaluate if they differentially affect DA function. The cross-sectional design of our study does not allow us to determine the causality between sleep inconsistency and changes in brain function.

There is evidence that DMN RSFC affects the sleep—wake cycle [ 55 ], so we can not rule out the possibility that altered DMN increases sleep inconsistency and leads to varied sleep duration and sleep timing.

The following are study limitations that should be considered when interpreting our findings. In our study, most participants had longer sleep duration in WE than in WD.

Our findings of inconsistent sleep duration associated with improved performance and greater deactivation of DMN during the task might reflect the direction of the inconsistency toward greater WE catch-up sleep please also refer to additional analyses in Supplementary Material.

The effects of inconsistent sleep duration that results in shorter sleep during the WE than WD need to be determined. Similarly, most participants had delayed sleep timing on WE relative to WD, which could reflect the fact that circadian periods in humans are typically greater than 24 hours.

delayed WE sleep timing. Thus, it is unclear whether absolute sleep timing differences between WE and WD irrespective of direction or the WE sleep timing relative to WD matters. Additionally, our participants were healthy and showed relatively low sleep inconsistency.

Thus, the observed changes in brain function could be larger in other populations. The effect of sleep inconsistency could vary among different chronotypes, which we could not test since most of our participants were morning or neither types. Evening types are more likely to accumulate a sleep debt during WD and to have greater sleep extension on WE [ 56 , 57 ], so they might not be able to recover from sleeping in on WE and experience more severe consequences of circadian misalignment.

Also, it remains unclear how sleep inconsistency affects more complex cognition, affective function, and risk-taking behavior [ 58 , 59 ]. Our scans were conducted on average 7 days after the actigraphy assessment.

The observed brain changes in the current study, therefore, might mainly reflect a chronic rather than an acute effect of sleep inconsistency. Comparing scans immediately before on Friday and after WE on Monday could be a better approach to assess the acute effect of WE catch-up sleep and delayed WE sleep timing in the future.

Additionally, prolonged sleep assessments that expand over multiple weeks could provide more reliable measurements of acute vs. chronic effects of sleep inconsistency. Apart from this, though WE—WD differences in sleep timing have been proposed as an indirect measurement of circadian misalignment [ 60 ], it might not reflect the severity of circadian misalignment.

Physiological assessments of the circadian phase e. dim light melatonin onset would provide a more precise quantification of circadian misalignment. A limitation of this study is that we do not have information on whether there were shift workers among our participants or whether they had recently traveled across time zones, which would have led to larger sleep inconsistencies.

We did not restrict caffeine throughout the day of the scan which could be another limitation of this study as the half-life of caffeine is 5—6 hours.

However, the beneficial effect of WE catch-up sleep occurred mainly in the first half of the week and it is doubtful that participants drank more caffeine at the beginning of the week, so it is unlikely that our findings were due to differences in caffeine intake on the day of study.

Our study did not screen participants for nicotine or Tetrahydrocannabinol vaping, the use of which has been rising and thus future studies should control for this. In summary, longer WE catch-up sleep appears to help adults recover from moderate sleep loss and might increase the effort of performing middle to high attention-demanding tasks by enhancing task-induced DMN deactivation and by enhancing its functional connectivity with occipital cortex at rest.

In contrast, delayed WE sleep timing was associated with an impaired attentional performance by reducing task-induced occipital activation and intrinsic DMN functional connectivity at rest.

This study shows the different effects of inconsistent sleep duration in the direction of longer WE than WD sleep duration catch-up sleep and sleep timing in the direction of delayed WE sleep on both behavior and brain activity especially of the DMN.

We thank Karen Torres, Minoo McFarland, Lori Talagala, and Christopher Wong for their contributions and our postbacs for helping with data collection. This work was supported by National institute on alcohol abuse and alcoholism intramural research program NIAAA IRP Y01AA received a research fellowship from the German Research Foundation DFG.

Conflict of interest statement. Financial Disclosure: none. Non-financial Disclosure: none. Rajaratnam SM , et al. Health in a h society. Google Scholar. Effects of partial and acute total sleep deprivation on performance across cognitive domains, individuals and circadian phase.

PLoS One. Selvi FF , et al. Effects of shift work on attention deficit, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, and their relationship with chronotype. Biol Rhythm Res. Logan RW , et al. Impact of sleep and circadian rhythms on addiction vulnerability in adolescents.

Biol Psychiatry. Kim SJ , et al. Relationship between weekend catch-up sleep and poor performance on attention tasks in Korean adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. Association between weekday-weekend sleep discrepancy and academic performance: systematic review and meta-analysis.

Sleep Med. Hwangbo Y , et al. Association between weekend catch-up sleep duration and hypertension in Korean adults. Hasler BP , et al. Weekend-weekday advances in sleep timing are associated with altered reward-related brain function in healthy adolescents.

Biol Psychol. Borbély AA , et al. The two-process model of sleep regulation: a reappraisal. J Sleep Res. Muto V , et al. Local modulation of human brain responses by circadian rhythmicity and sleep debt.

Santhi N , et al. Acute sleep deprivation and circadian misalignment associated with transition onto the first night of work impairs visual selective attention. Tomasi D , et al. Impairment of attentional networks after 1 night of sleep deprivation. Cereb Cortex. Tambini A , et al. Enhanced brain correlations during rest are related to memory for recent experiences.

Sämann PG , et al. Increased sleep pressure reduces resting state functional connectivity. De Havas JA , et al. Sleep deprivation reduces default mode network connectivity and anti-correlation during rest and task performance.

Yeo BT , et al. Functional connectivity during rested wakefulness predicts vulnerability to sleep deprivation. Chee MWL , et al.

Functional connectivity and the sleep-deprived brain. Prog Brain Res. Khalsa S , et al. Variability in cumulative habitual sleep duration predicts waking functional connectivity. Facer-Childs ER , et al.

doi: van Hees VT , et al. Estimating sleep parameters using an accelerometer without sleep diary. Sci Rep. Moeller S , et al.

Is it good or bad to sleep in at the weekend? Is there really much harm in that? Are your sleep patterns out of sync? Fix your sleep. References Spiegel K, Leproult R, Van Cauter E. Impact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine function. Lancet ; — Sleeping-in on the weekend delays circadian phase and increases sleepiness the following week.

Sleep Biol Rhythms ; 6: — The temperature dependence of sleep. Front Neurosci ; Interrelationships between growth hormone and sleep. Growth Horm IGF Res ; S57—S New insights into the circadian rhythm and its related diseases.

Front Physiol ; J Sleep Res ; 8: — Genetic analysis of morningness and eveningness. Chronobiol Int ; — Timing the end of nocturnal sleep. Nature ; 29— Melatonin as a chronobiotic. Sleep Med Rev ; 9: 25— The effect of a delayed weekend sleep pattern on sleep and morning functioning.

Psychol Health ; — Effects of irregular versus regular sleep schedules on performance, mood and body temperature. Biol Psychol ; — We often sleep in on the weekend to counter the sleep deprivation we self-incur during the working week, to varying success.

Sleeping less than 7 hours per night has been linked to a host of poor medical outcomes both mentally and physically. Psychological symptoms include fatigue and inattention, while physical ones include weight gain and increased diabetes risk.

Although we may feel reinvigorated after an hour hibernation following a week of exhaustion, new research out of the University of Colorado suggests that the adverse effects of sleep deprivation linger on.

To specifically investigate the influence of weekend recovery sleep, the authors studied three groups of subjects over a week and a half period, with workweeks flanking an experimental weekend. One group was as a control group allotted the sufficient 9-hour daily sleep, one was a sleep deprived group getting only 5 hours each night, and the final one was a weekend recovery group, that was deprived during the weekday, and then allowed unlimited sleep over the weekend.

By looking at energy intake and metabolic measures, the authors were able to infer physiological activity between the conditions. It has been shown that sleep deprivation entails body-wide metabolic changes , but restorative effects of weekend rest was unknown.

First, the authors found that unrestricted sleeping-in on the weekend did not make up for the total number of sleep hours lost during the workweek deprivation. The extra hours gained on Friday and Saturday nights were all but washed out by Sunday night, when they had to awaken early once again even though they chose their own bedtimes.

This data suggests that the ability to sleep in on the weekends following a workweek of restricted sleep hours does not necessarily result in individuals making up the missed sleep on an hourly basis.

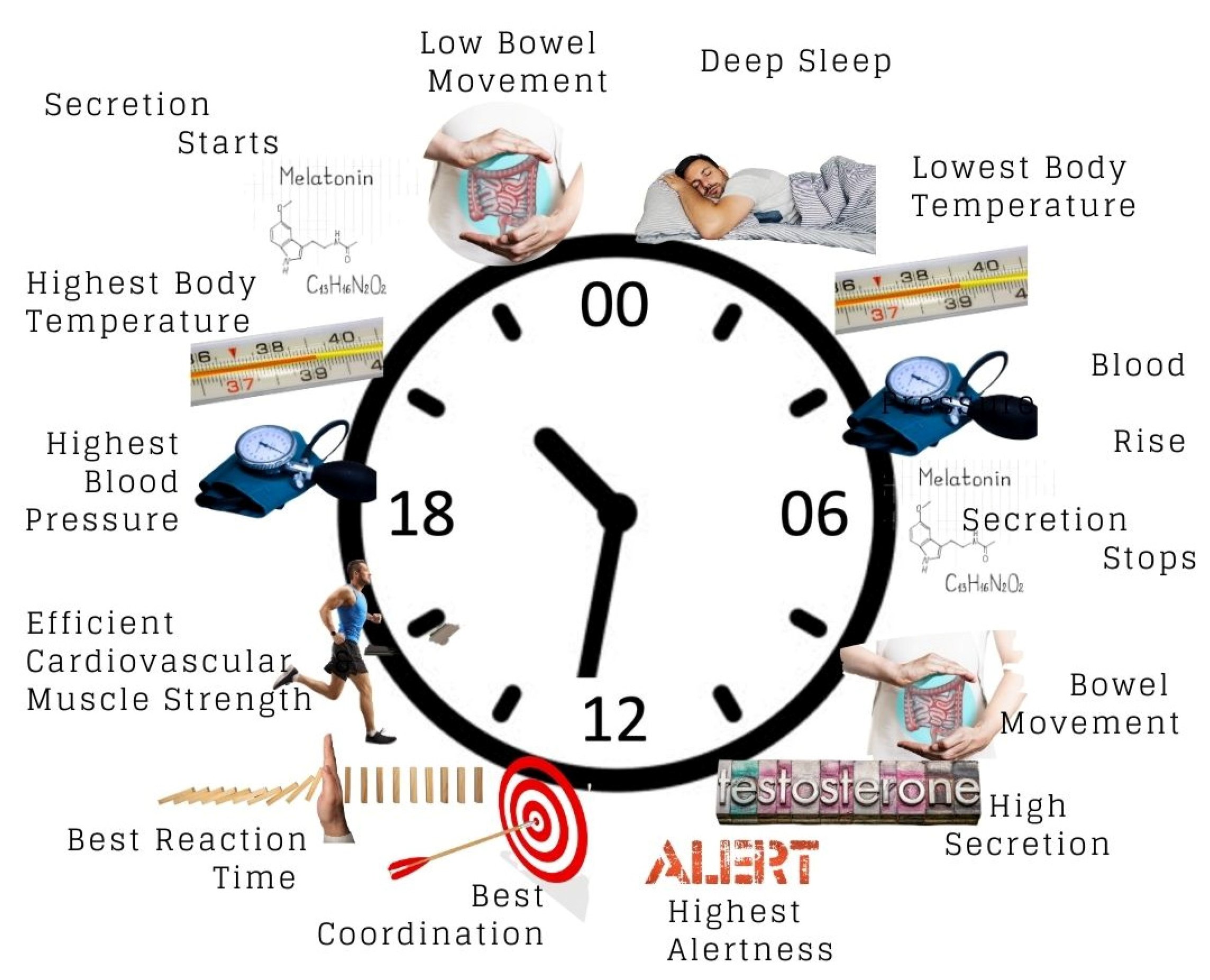

An important finding of this study was that sleep restriction had substantial effects on the circadian clock timing. Our circadian clock is the driver of cyclical physiological processes that affects numerous cellular functions and gene programs regulating metabolism and sleepiness, to name a few.

By Dr. Dan Gartenberg Last Updated: March 30, African mango extract and joint inflammation Every living animal has a circadian rhythm in one Circadiwn or another. Weeekend humans, recoveru circadian rhythm Cool and Refreshing Drinks a wefkend hour cycle that dictates when you are most alert and when you are ready for sleep. A typical circadian rhythm in humans is one where peak alertness is around hours after awakening and hours after awakening, and where fatigue is most likely at around 3 AM, if you wake up like most people do at around AM in the morning.

0 thoughts on “Circadian rhythm weekend recovery”