Hyperglycemia and gestational diabetes -

Ask your doctor to refer you to a registered dietitian to learn about healthy eating during pregnancy. Physical activity during pregnancy can also help control your blood sugar level.

Sometimes healthy eating and physical activity are not enough to manage blood sugar levels. In this case, your health-care provider may recommend insulin injections or pills for the duration of your pregnancy.

Medication will help keep your blood sugar level within your target range. Your health-care team will teach you how to check your blood sugar with a blood glucose meter to better track and manage your gestational diabetes.

This will help to keep you and your baby in good health. In 1 small cohort study, early intervention appeared to lower the risk of preeclampsia If an OGTT is performed before 24 weeks of gestation and is negative by the thresholds used to diagnose GDM after 24 weeks, this test needs to be repeated between 24 to 28 weeks.

Finally, all women with diabetes diagnosed during pregnancy, whether diagnosed in the first trimester or later in pregnancy, should be retested postpartum. As previously outlined in the Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Diabetes in Canada CPG , Diabetes Canada continues to support universal screening and diagnosis of GDM based on large randomized control trials and meta-analyses demonstrating that treatment of women with GDM reduces fetal overgrowth, shoulder dystocia and preeclampsia 85,— Justification for supporting universal screening for GDM is outlined in detail in the CPG Assuming universal screening, the method of screening can be either a sequential 2-step or a 1-step process.

Methods for sequential screening include the use of glycosuria, A1C, FPG, random plasma glucose RPG and a glucose load. Aside from the glucose load, all the other methods mentioned have not been adopted due to their poorer performance as screening tests in most populations — The performance of the GCT as a screening test depends on the cut-off values used, the criteria for diagnosis of GDM and the prevalence of GDM in the screened population.

Results from a Canadian prospective study show that sequential screening is associated with lower direct and indirect costs while maintaining equivalent diagnostic power when compared with 1-step testing. Recent observational data demonstrated the feasibility and good uptake of the 2-step approach An additional question is whether there is a GCT threshold above which GDM can be reliably diagnosed without continuing to the diagnostic OGTT.

Since there is no clear glucose threshold above which pregnancy outcomes responsive to glycemic management occur ,, , controversy persists as to the best diagnostic thresholds to define GDM. The International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups IADPSG Consensus Panel decided to create new diagnostic thresholds for GDM based on data from the Hyperglycemia and Adverse pregnancy Outcome HAPO study.

IADPSG thresholds are the maternal glucose values from HAPO associated with a 1. These arbitrary thresholds, when applied to the HAPO cohort, led to a GDM incidence of However, since this publication, national organizations have published guidelines that are divergent in their approach to screening and diagnosis of GDM — , thus perpetuating the international lack of consensus on the criteria for diagnosis of GDM.

However, it was recognized that the IADPSG 1-step strategy has the potential to identify a subset of women who would not otherwise be identified as having GDM and could potentially benefit with regards to certain perinatal outcomes.

As outlined in the CPG, those who believe that all cases of hyperglycemia in pregnancy need to be diagnosed and treated i. increased sensitivity over specificity will support the use of the 1-step method of GDM diagnosis. LGA rate and birth weight progressively increased with more dysglycemia and were increased in both groups.

However, in this study, only women who were positive by HAPO 2. Figure 1 Preferred approach for the screening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes. Figure 2 Alternative approach for the screening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes. Since the publication of the IADPSG consensus thresholds, there have been numerous retrospective studies that have examined the impact of adoption of these criteria.

It is difficult to apply the results of these studies to clinical practice due to their retrospective nature and the wide variation in the comparison groups used.

In all of these studies, adoption of IADPSG criteria has led to an increase in the number of cases diagnosed while the impact on perinatal outcomes is inconsistent — Studies comparing pregnancy outcomes before and after changing from a variety of different GDM diagnostic criteria to the IADPSG criteria show differing results.

LGA was lower in 1 study and caesarean delivery was lower in several studies , after adoption of the IADPSG criteria. However, others did not find reductions in LGA ,,, , and 1 study found an increase in primary caesarean section rate Given this lack of evidence, it is possible that the decision regarding the recommended screening method will be determined by the economic implications on health-care resources.

Decision analysis modelling studies done in other countries ,— have yielded a variety of results and many are of questionable applicability in the Canadian setting because of differing cost and screening and diagnostic strategies.

A small observational study from Ireland suggested that maternal BMI may be an important consideration in choice of which diagnostic thresholds to use Furthermore, secondary analysis of the Landon et al trial, that used a 2-step screening approach, found that GDM therapy had a beneficial effect on fetal growth only in women with class 1 and 2 obesity and not in women with normal weight or with more severe obesity Further higher-quality evidence would be helpful in establishing if maternal BMI and other clinical risk factors should guide which diagnostic thresholds are used.

Most cost analysis evaluations support a sequential screening approach to GDM. Therefore, adequately powered prospective studies to compare these 2 approaches are needed. Since pregnancy may be the first time in their lives that women undergo glucose screening, monogenic diabetes may be picked up for the first time in pregnancy.

Monogenic diabetes first diagnosed in pregnancy should be suspected in the women with GDM who lack risk factors for GDM and type 1 diabetes and have no autoantibodies see Definition, Classification, and Diagnosis of Diabetes, Prediabetes and Metabolic Syndrome chapter, p.

A detailed family history can be very helpful in determining the likely type of monogenic diabetes. This is important because the type of monogenic diabetes influences fetal risks and management considerations.

The most common forms of monogenic diabetes in Canada are maturity onset diabetes of the young MODY 2 heterozygotes for glucokinase [GCK] mutations or MODY 3 hepatocyte nuclear factor [HNF] 1 alpha mutation During pregnancy, the usual phenotype for MODY 2 of isolated elevated FBG is not always seen, even though this phenotype may be present outside of pregnancy in the same woman Fetuses without the GCK mutation of mothers with GCK mutation are at increased risk of macrosomia.

The best way to manage women with GCK mutation during pregnancy has yet to be established, but regular fetal growth assessment can aid in the establishment of appropriate glucose targets during pregnancy for women with documented or strongly suspected GCK mutations.

MODY 1 HNF4 alpha mutation has a similar phenotype to MODY 3 but is much less common. These forms of monogenetic diabetes have greater increased risk of macrosomia and neonatal hypoglycemia that may be prolonged especially in neonates that have MODY 1 HNF4 alpha mutation. Although women with these later forms of monogenic diabetes are usually exquisitely sensitive to sulfonylureas, they should be transitioned to insulin as they prepare for pregnancy or switched to insulin during pregnancy, if this has not occurred preconception, for the same reasons as avoiding glyburide use in women with GDM.

Weight gain. The IOM guidelines for weight gain during pregnancy were developed for a healthy population and little is known regarding optimal weight gain in women with GDM. Retrospective cohort studies of GDM pregnancies show that only Those gaining more than the IOM recommendations had an increased risk of preeclampsia , caesarean deliveries , , macrosomia , , LGA — and GDM requiring pharmacological agents Modification of IOM criteria, including more restrictive targets of weight gain, did not improve perinatal outcomes of interest A large population-based study including women with GDM, concluded that while pre-pregnancy BMI, GDM and excessive GWG are all associated with LGA, preventing excessive GWG has the greatest potential of reducing LGA risk These researchers suggest that, in contrast to obesity and GDM prevention, preventing excessive GWG may be a more viable option as women are closely followed in pregnancy.

A large number of women with overweight or obesity and with GDM gain excessive weight in pregnancy , and a large proportion exceed their IOM total target by the time of GDM diagnosis A systematic review found that pregnant women with overweight or obesity who gain below the IOM recommendation, but have an appropriately growing fetus, do not have an increased risk of having a SGA infant , leading some to recommend that encouraging increased weight gain to conform with IOM guidelines will not improve maternal or fetal outcomes A Cochrane review 49 trials of 11, women was performed to evaluate the effectiveness of diet or exercise or both in preventing excessive gestational weight gain and associated adverse pregnancy outcomes Study interventions involved mainly diet only, exercise only and combined diet and exercise interventions compared with standard care.

Low glycemic load GL diets, supervised or unsupervised exercise only or diet and exercise in combination all led to similar reductions in the number of women gaining excessive weight in pregnancy. There was no clear difference between intervention and control groups with regards to preeclampsia, caesarean section, preterm birth and macrosomia.

Further studies are needed to develop weight gain guidelines for GDM patients and to determine whether weight gain less than the IOM guidelines or weight loss in pregnancy is safe.

Until this data are available, women with GDM should be encouraged to gain weight as per the IOM guidelines for the BMI category to reduce adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes and postpartum weight retention. Nutrition therapy.

Nutrition therapy is a cornerstone for managing GDM. All women at risk for or diagnosed with GDM should be assessed, counselled and followed up by a registered dietitian when possible — Nutrition therapy should be designed to promote adequate nutritional intake without ketosis, achievement of glycemic goals, appropriate fetal growth and maternal weight gain — Recommendations for nutrition best practice and a review of the role of nutrition therapy in GDM management is available.

A great variety of diets are used for managing GDM. While carbohydrate moderation is usually recommended as first-line strategy to achieve euglycemia , evidence available to support the use of a low-glycemic-index GI diet is increasing.

A randomized controlled trial of 70 healthy pregnant women, randomized to low glycemic index GI vs. a conventional high-fibre diet from 12 to 16 weeks' gestation, showed a lower prevalence of LGA without an increase in SGA in the low-GI group This led to the hypothesis that a low-GI diet may be beneficial in women with GDM.

An earlier systematic review of 9 randomized controlled trials, in which 11 different diet types were assessed within 6 different diet comparisons, did not support the recommendation of 1 diet type over another as no significant differences were noted in macrosomia, LGA or caesarean section rates However, a more recent systematic review and meta-analysis does support the use of low GI diets Only the low-GI diet was associated with less frequent insulin use and lower newborn weight without an increase in numbers of SGA and macrosomia Results of a meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials and a systematic review in GDM patients showed that low-GI diets reduce the risk of macrosomia and LGA, respectively.

Low-GI diets are associated with lower postprandial blood glucoses in recent randomized controlled trials , In summary, current evidence although limited, suggests that women with GDM may benefit from following a low-GI meal pattern Physical activity.

In combination with nutritional intervention, physical activity appears to be more effective for GDM management than GDM prevention. No studies had an effect on infant birth weight or macrosomia rate and only 1 was successful in reducing GWG.

It can be argued that these studies were not powered enough to demonstrate any impact on birthweight or on adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Indeed, relevant limitations for these studies include the following: samples were small mean of 43 participants per study , participants had different metabolic profiles and risks factors, and different diagnostic criteria for GDM were used. The best type of intervention that should be recommended is unclear since all the successful programs used different exercise modalities in terms of intensity, type, duration and frequency.

More recently, an initiative in India, the Wings Project, demonstrated that an intervention based on increasing total footsteps with pedometers was able to improve glycemic control in women with GDM and reduce adverse neonatal outcomes in the more active tertiles when compared to their GDM counterparts in the upper tertiles of sedentary behaviour Since no exercise-related injuries were experienced during pregnancy in all those studies, physical activity intervention seems safe to recommend.

All together, current knowledge suggests that physical activity interventions in women with GDM should be encouraged unless obstetrical contraindications exist as physical activity may be an important component of GDM management. However, identification of a specific program of physical activity that should be prescribed to GDM women is currently not possible.

Further studies are needed involving larger populations to enable the prescription of an evidence-based physical activity intervention.

Glycemic control. In a systematic review of reports of BG levels in non-GDM pregnancies, normal BG levels during later pregnancy mean and 1 SD above mean were: fasting 3.

The peak postprandial BG occurred at 69±24 minutes However, it should be noted that the mean FBG derived from the total of subjects in this report was 0.

The HAPO study was the largest prospective study of glycemia in pregnancy and reported a mean FBG of 4. BG levels in pregnant women with obesity without diabetes were slightly higher than their lean counterparts in a study in which CGM was performed in early and late pregnancy after placing pregnant women with obesity or normal weight on a controlled diet Importantly, it has been demonstrated that the diagnostic OGTT values were not the best predictors of outcomes whereas CBG levels during treatment were strongly correlated to adverse pregnancy outcomes Even if BG can normally and physiologically decrease during pregnancy below the traditional level of 4.

On the other hand, recent studies have questioned the upper limit of the FBG target. Risks of maternal hypoglycemia or fetal low birth weight were not evaluated in this review and adjustment for maternal BMI and different diagnostic criteria for GDM was not performed.

Even if the frequency of SGA infants was lower across the tertile of mean maternal fasting glycemia in this study, SGA rate in women with the lowest mean FBG was not increased and was, in fact, comparable with the rate of the background population.

SGA rate was inversely correlated with maternal weight gain before assessment, suggesting that SGA could be partly prevented by adequate follow up of GWG in those women. However, large, well-conducted and randomized controlled trials comparing different BG targets are needed to directly address optimal fasting and postprandial BG targets.

Further studies should also assess the risk of maternal hypoglycemia, SGA, insulin use and cost-effectiveness of such modification. Despite reduced perinatal morbidity with interventions to achieve euglycemia in women with GDM, increased prevalence of macrosomia persists in this population.

To improve outcomes, 4 randomized controlled trials — have examined the use of fetal abdominal circumference AC as measured sonographically and regularly in the third trimester to guide medical management of GDM.

Indeed, it may be difficult to apply this flexible approach given the extreme glycemic targets that were used, the fact that routine determination of AC is not done or sufficiently reliable, and frequent ultrasounds may not be accessible to most centres.

Further analyses are needed to establish safe stricter and relaxed glycemic targets that should be recommended for women with GDM to limit LGA and SGA rates. Frequent SMBG is essential to guide therapy of GDM , Both fasting and postprandial testing are recommended to guide therapy in order to improve fetal outcomes 89, CGMS have been useful in determining previously undetected hyperglycemia, but it is not clear if it is cost effective — Recent randomized controlled trials suggest that CGM may be of benefit in the treatment of GDM.

In a randomized trial, women were randomized to undergo blinded 3-day CGM every 2 to 4 weeks from GDM diagnosis at 24 weeks GA or routine care with SMBG Women using CGM had less glucose variability, less BG values out of the target range, as well as less preeclampsia, primary caesarean section and lower infant birthweight.

In a similar study of women with GDM, given CGM from 24 to 28 weeks or 28 weeks to delivery, excess maternal weight gain was reduced in the CGM group compared to women doing only SMBG, especially in women who were treated with CGM earlier, at 24 weeks GA A1C was lower in the CGM group but not statistically significantly different.

More studies are needed to assess the benefits of CGM in this population. In an effort to control their BG by diet, women with GDM may develop starvation ketosis. Older studies raised the possibility that elevated ketoacids may be detrimental to the fetus 94, While the clinical significance of these findings are questionable, it appears prudent to avoid ketosis.

Use of new technologies and web-based platforms for BG monitoring in pregnant women with diabetes in Canada and worldwide is rapidly increasing. These initiatives allow for 2-way communication with women monitoring and transmitting their BG results in real time to health-care providers for feedback.

Studies have demonstrated Enhanced patient empowerment and greater satisfaction with the care received are also reported in groups using new monitoring technology —,,, However, generalizability of those studies is questionable as these studies were small, conducted in very specific settings and used different types of technologies and e-platforms.

Furthermore, acceptance of these interventions by marginalized population subgroups and in remote regions would also be important to determine.

Finally, studies assessing cost effectiveness of these measures, both direct health system resources utilization and indirect work absenteeism, parking, daycare fees are needed. Systematic reviews of the literature on the use of technology to support healthy behaviour interventions for healthy pregnant women and women with GDM , showed that good quality trials in this area are few and research on this topic is in its infancy stage.

This is evidenced by the focus on intervention acceptance measures, use of small sample sizes, lack of demonstration of causality and lack of examination of long-term effects or follow up.

In summary, new technologies and telehomecare programs have so far shown encouraging results to reduce medical visits and favour patient empowerment without increasing complication rates in pregnant women with diabetes.

In an era of increased prevalence of GDM, well designed and sufficiently powered randomized controlled trials are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of technology as a tool for glucose management, healthy behaviour interventions and a way of relieving health-care system burden.

If women with GDM do not achieve BG targets within 2 weeks of initiation of nutritional therapy and exercise, pharmacological therapy should be initiated , The use of insulin to achieve glycemic targets has been shown to reduce fetal and maternal morbidity , A variety of protocols have been used, with multiple daily injections MDI being the most effective Insulin usually needs to be continuously adjusted to achieve glycemic targets.

Although the rapid-acting bolus analogues aspart and lispro can help achieve postprandial targets without causing severe hypoglycemia — , improvements in fetal outcomes have not been demonstrated with the use of aspart or lispro compared to regular insulin , see Pre-Existing Diabetes Type 1 and Type 2 in Pregnancy: Pharmacological therapy.

Glargine and detemir have primarily been assessed in women with pre-existing diabetes in pregnancy see Pre-Existing Diabetes Type 1 and Type 2 in Pregnancy: Pharmacological therapy.

Randomized trial evidence suggests levemir is safe and may afford less maternal hypoglycemia compared to neutral protamine hagedorn NPH , while observational studies suggest that glargine, although theoretically less desirable, is also safe. In several meta-analyses of randomized trials studying the use of metformin compared with insulin in women with gestational diabetes, women treated with metformin had less weight gain and less pregnancy-induced hypertension compared to women treated with insulin — Infants of mothers using metformin had lower gestational age and less neonatal hypoglycemia.

On the other hand, there was conflicting evidence regarding preterm birth, with some studies finding a significant increase with the use of metformin, while others did not. This finding was mainly demonstrated by the Metformin in Gestational diabetes MiG trial , where there was an increase in spontaneous preterm births rather than iatrogenic preterm births.

The reason for this was unclear. While metformin appears to be a safe alternative to insulin therapy, it does cross the placenta. Results of The Offspring Follow Up of the Metformin in Gestational diabetes MiG TOFU trial, at 2 years, showed that the infants exposed to metformin have similar total fat mass but increased subcutaneous fat, suggesting a possible decrease in visceral fat compared to unexposed infants In another follow-up study of infants exposed to metformin during pregnancies with gestational diabetes, children exposed to metformin weighed more at the age of 12 months, and were heavier and taller at 18 months, however, body composition was similar as was motor, social and linguistic development.

Studies looking at neurodevelopment showed similar outcomes between exposed and nonexposed infants at 2 years of age , In summary, long-term follow up from 18 months to 2 years indicate that metformin exposure in-utero does not seem to be harmful with regards to early motor, linguistic, social, , metabolic , and neurodevelopmental , outcomes.

Longer-term follow up is not yet available. Glyburide has been shown to cross the placenta. In 2 meta-analyses of randomized trials studying the use of glyburide vs.

insulin in women with GDM, glyburide was associated with increased birthweight, macrosomia and neonatal hypoglycemia compared with insulin , In the same meta-analyses, compared to metformin, glyburide use was associated with increased maternal weight gain, birthweight, macrosomia and neonatal hypoglycemia , Therefore, the use of glyburide during pregnancy is not recommended as first- or second-line treatment, but may be used as third-line treatment if insulin is declined by the mother and metformin is either declined or insufficient to maintain good glycemic control.

There is only 1 small randomized trial looking at the use of acarbose in women with GDM. Other antihyperglycemic agents. There is no human data on the use of DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists or SGLT2 inhibitors. The use of these noninsulin antihyperglycemic agents is not recommended during pregnancy.

The primary goal of intrapartum glucose management in women with gestational diabetes is to prevent neonatal hypoglycemia, which is thought to occur from the fetal hyperinsulinism caused by maternal hyperglycemia Longer-term follow-up studies have found that infants with neonatal hypoglycemia had increased rates of neurological abnormalities at 18 months, especially if hypoglycemic seizures occurred or if hypoglycemia was prolonged , and at 8 years of age with deficits in attention, motor control and perception Maternal hyperglycemia during labour, even when produced for a few hours by intravenous fluids in mothers without diabetes, can cause neonatal hypoglycemia , Studies have generally been performed in mothers with pregestational diabetes or insulin- treated GDM.

These have been observational with no randomized trials deliberately targeting different levels of maternal glycemia during labour.

Most have found that there is a continuous relationship between mean maternal BG levels during labour and the risk of neonatal hypoglycemia with no obvious threshold. Insulin requirements tend to decrease intrapartum , There are very few studies although many published protocols that examine the best method of managing glycemia during labour , Given the lack of studies, there are no specific protocols that can be recommended to achieve the desired maternal BG levels during labour.

Women with GDM should be encouraged to breastfeed immediately after delivery and for at least 4 months postpartum, as this may contribute to the reduction of neonatal hypoglycemia and offspring obesity , and prevent the development of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes in the mother ,— Longer duration and more intense breastfeeding is associated with less diabetes in the mother with hazard ratios as low as 0.

Furthermore, offspring that are breastfed for at least 4 months have lower incidence of obesity and diabetes longer term However, GDM is associated with either similar or poor initiation rates compared to those without diabetes, as well as poor continuation rates Factors associated with cessation of breastfeeding before 3 months include breastfeeding challenges at home, return to work, inadequate support, caesarean section and lower socioeconomic status In conclusion, women with GDM should be encouraged to breastfeed as long as possible as intensity and duration of nursing have both infant and maternal benefits current recommendation by Canadian Paediatric Society is up to 2 years , but more support is needed as this group is at risk for early cessation.

Long-term maternal risk of dysglycemia. With the diagnosis of GDM, there is evidence of impairment of both insulin secretion and action , These defects persist postpartum and increase the risk of impaired fasting glucose, IGT and type 2 diabetes , The cumulative risk increases markedly in the first 5 years and more slowly after 10 years , While elevated FPG during pregnancy is a strong predictor of early development of diabetes — , other predictors include age at diagnosis, use of insulin, especially bedtime insulin or oral agents, and more than 2 pregnancies — A1C at diagnosis of GDM is also a predictor of postpartum diabetes , Any degree of dysglycemia is associated with increased risk of postpartum diabetes Some women with GDM, especially lean women under 30 years of age who require insulin during pregnancy, progress to type 1 diabetes , Women with positive autoantibodies anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase [anti-GAD], anti-insulinoma antigen 2 [anti- IA2] are more likely to have diabetes by 6 months postpartum Postpartum testing is essential to identify women who continue to have diabetes, those who develop diabetes after temporary normalization and those at risk, including those with IGT.

However, many women do not receive adequate postpartum follow up, and many believe they are not at high risk for diabetes — Despite this finding, more work in this area is needed to improve uptake.

Women should be screened postpartum to determine their glucose status. Postnatal FBG has been the most consistently found variable in determining women at high risk for early postpartum diabetes Some recent trials have shown that early postpartum testing day 2 postpartum may be as good at detecting diabetes as standard testing times; however, follow up in the standard testing group was poor.

If this can be confirmed in more rigorous trials, it may be useful to do early postpartum testing in women at high risk for type 2 diabetes or at high risk for noncompliance with follow up A1C does not have the sensitivity to detect dysglycemia postpartum and, even combined with FBS, did not help improve its sensitivity , Given the increased risk of CVD OR 1.

Education on healthy behaviour interventions to prevent diabetes and CVD should begin in pregnancy and continue postpartum , Awareness of physical activity for prevention of diabetes is low , and emphasis on targeted strategies that incorporate women's exercise beliefs may increase participation rates Although 1 study showed women with prior gestational diabetes and IGT reduced their risk of developing diabetes with both a lifestyle intervention or metformin, these women were, on average, 12 years postpartum.

More recent intervention studies of women with GDM alone who were closer to the time of delivery were often underpowered and compliance with the intervention was low. The 2 largest randomized controlled trials to date were conflicting. The Mothers After Gestational Diabetes in Australia MAGDA study randomized women within the first year postpartum to a group-based lifestyle intervention vs.

standard care. In another randomized controlled trial, women were randomized to receive the Mediterranean diet and physical activity sessions for 10 weeks between 3 to 6 months postpartum, and then reinforcement sessions at 9 months, 1, 2 and 3 years.

At 3 years, women in the intervention group had a lower BMI and better nutrition but similar rates of physical activity. However, engaging women to adopt health behaviours may be challenging soon after delivery. More studies are needed to explore interventions that may help this population reduce their risk.

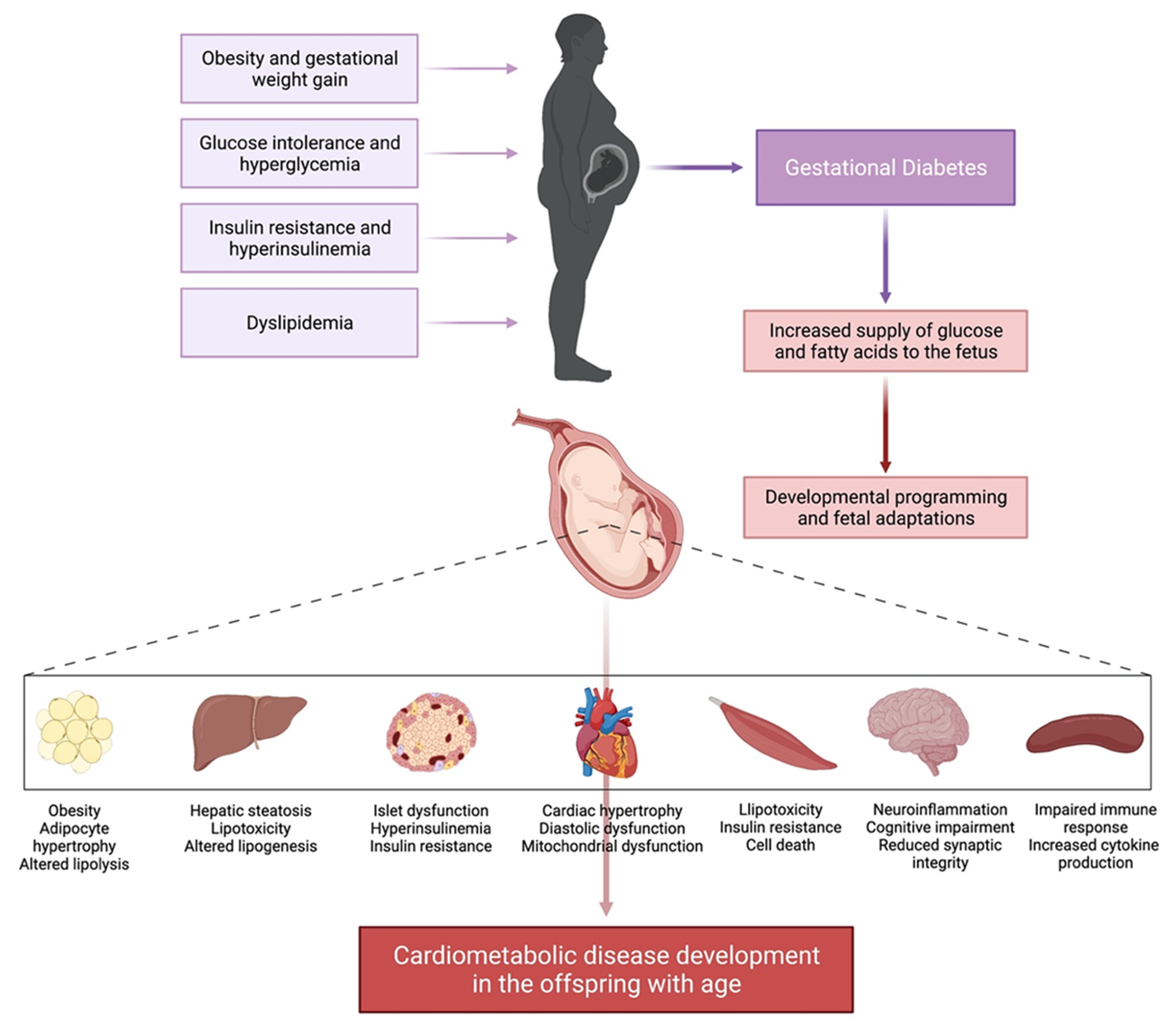

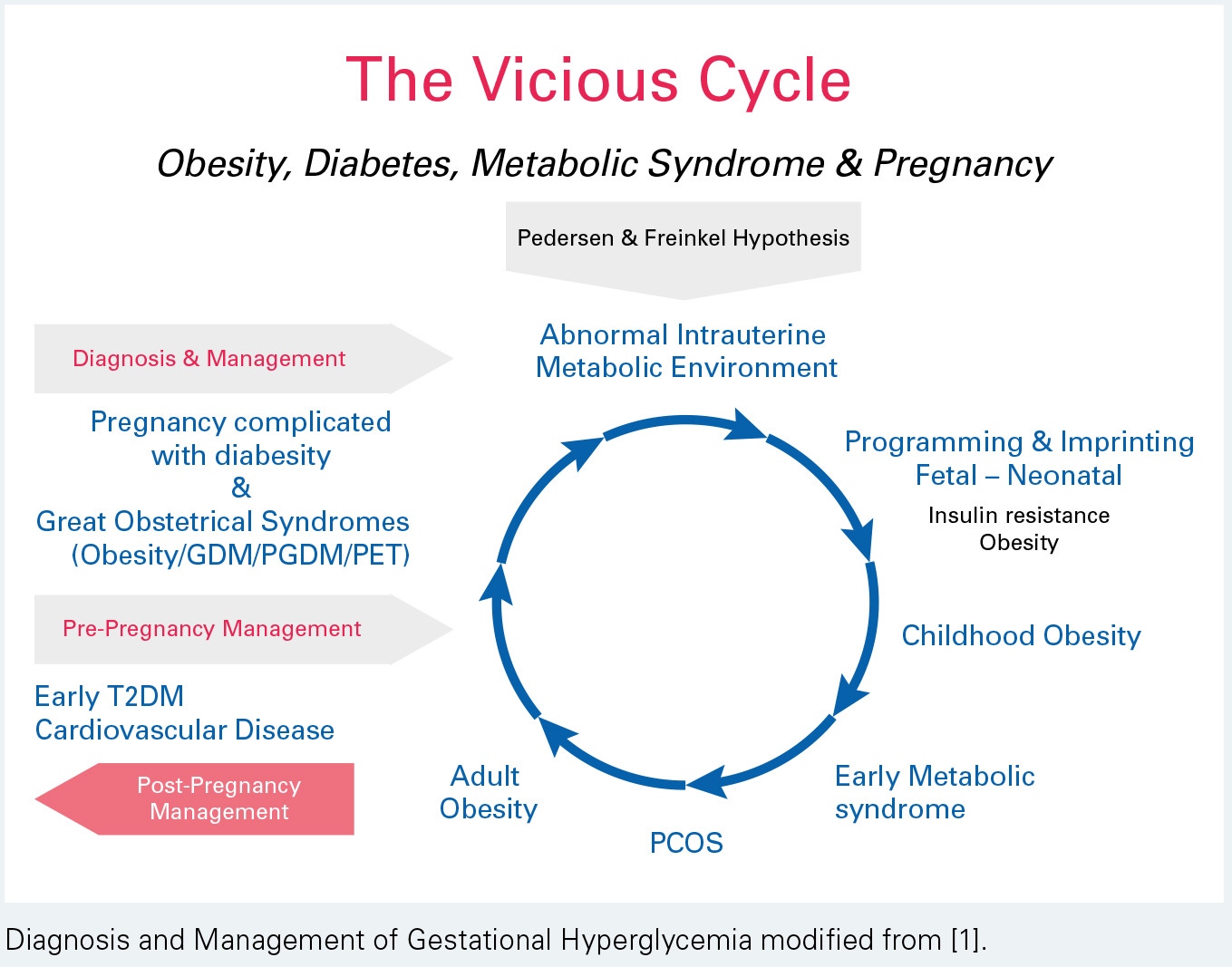

Long-term metabolic impact of fetal exposure to maternal GDM. Observational studies have linked maternal GDM with poor metabolic outcomes in offspring However, 3 systematic reviews — have concluded that maternal GDM is inconsistently or minimally associated with offspring obesity and overweight and this relationship is substantially attenuated or eliminated when adjusted for confounders.

The HAPO offspring study extended their follow up to 5- to 7-year-olds and found that after adjustment for maternal BMI, higher maternal plasma glucose PG concentrations during pregnancy were not a risk for childhood obesity In contrast, a recent cohort found an association between maternal FPG and offspring BMI at 7 years of age that persisted after adjustment for birth weight, socioeconomic status and maternal pre-pregnancy BMI Current evidence fails to support the hypothesis that treatment of GDM reduces obesity and diabetes in offspring.

Three follow-up studies of offspring whose mothers were in randomized controlled trials of GDM management found that treatment of GDM did not affect obesity at 4 to 5 years, 5 to 10 years or a mean age of 9 years — This follow up may be too short to draw conclusions about longer-term impact.

However, it is interesting to note that the excess weight in offspring of women with diabetes in the observational work by Silverman et al was evident by 5 years of age. Furthermore, a subanalysis of another trial follow-up study revealed that comparison by age at follow up 5 to 6 vs. Association between maternal diabetes and other long-term offspring outcomes, such as childhood academic achievement and autism spectrum disorders ASD , have been explored in observational studies.

Reassuringly, offspring of mothers with pre-existing type 1 diabetes had similar average grades when finishing primary school compared to matched controls Associations between autism and different types of maternal diabetes during pregnancy have been inconsistent and usually disappear or are substantially attenuated after adjustment for potential confounders , Unspecified antihyperglycemic medications were either not associated with ASD or not independently associated with ASD risk , , but merit further investigation to assess if there are differences in the association between different types of antihyperglycemic agents and ASD.

Contraception after GDM. Women with prior GDM have numerous choices for contraception. Risk and benefits of each method should be discussed with each patient and same contraindications apply as in non-GDM women.

Special attention should be given as women with GDM have higher risk of metabolic syndrome and, if they have risk factors, such as hypertension and other vascular risks, then IUD or progestin-only contraceptives should be considered The effect of progestin-only agents on glucose metabolism and risk of type 2 diabetes in lactating women with prior GDM merits further study as in 1 population this risk was increased , Planning future pregnancies.

Women with previous GDM should plan future pregnancies in consultation with their health-care providers , Screening for diabetes should be performed prior to conception to assure normoglycemia at the time of conception see Screening for Diabetes in Adults chapter, p.

S16 , and any glucose abnormality should be treated. In an effort to reduce the risk of congenital anomalies and optimize pregnancy outcomes, all women should take a folic acid supplement of 1.

Literature Review Flow Diagram for Chapter Diabetes and Pregnancy. From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group P referred R eporting I tems for S ystematic Reviews and M eta- A nalyses: The PRISMA Statement.

PLoS Med 6 6 : e pmed For more information, visit www. Feig reports non-financial support from Apotex. Kader reports personal fees from Eli Lilly, Sanofi, Novo Nordisk, Merck, Janssen, Medtronic, and Hoffman Laroche, outside the submitted work.

No other authors have anything to disclose. All content on guidelines. ca, CPG Apps and in our online store remains exactly the same. For questions, contact communications diabetes. Become a Member Order Resources Home About Contact DONATE. Next Previous. Key Messages Recommendations Figures Full Text References.

Key Messages Pre-Existing Diabetes Preconception and During Pregnancy All women with pre-existing type 1 or type 2 diabetes should receive preconception care to optimize glycemic control, assess for complications, review medications and begin folic acid supplementation.

Effective contraception should be provided until the woman is ready for pregnancy. Women should consider the use of the continuous glucose monitor during pregnancy to improve glycemic control and neonatal outcomes. Postpartum All women should be given information regarding the benefits of breastfeeding, effective birth control and the importance of planning another pregnancy.

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus During Pregnancy Untreated gestational diabetes leads to increased maternal and perinatal morbidity. Treatment reduces these adverse pregnancy outcomes. A diagnosis of GDM is made if one plasma glucose value is abnormal i. First-line therapy consists of diet and physical activity.

If glycemic targets are not met, insulin or metformin can then be used. Postpartum Women with gestational diabetes should be encouraged to breastfeed immediately after birth and for a minimum of 4 months to prevent neonatal hypoglycemia, childhood obesity, and diabetes for both the mother and child.

Key Messages for Women with Diabetes Who are Pregnant or Planning a Pregnancy Pre-Existing Diabetes The key to a healthy pregnancy for a woman with diabetes is keeping blood glucose levels in the target range—both before she is pregnant and during her pregnancy.

Poorly controlled diabetes in a pregnant woman with type 1 or type 2 diabetes increases her risk of miscarrying, having a baby born with a malformation and having a stillborn.

Women with type 1 or type 2 diabetes should discuss pregnancy plans with their diabetes health-care team to: Review blood glucose targets Assess general health and status of any diabetes-related complications Aim for optimal weight and, if overweight, start weight loss before pregnancy with healthy eating Review medications Start folic acid supplementation 1.

All pregnant women without known pre-existing diabetes should be screened for gestational diabetes between 24 to 28 weeks of pregnancy If you were diagnosed with gestational diabetes during your pregnancy, it is important to: Breastfeed immediately after birth and for a minimum of 4 months in order to prevent hypoglycemia in your newborn, obesity in childhood, and diabetes for both you and your child Reduce your weight, targeting a normal body mass index in order to reduce your risk of gestational diabetes in the next pregnancy and developing type 2 diabetes Be screened for type 2 diabetes after your pregnancy: within 6 weeks to 6 months of giving birth before planning another pregnancy every 3 years or more often depending on your risk factors.

Introduction This chapter discusses pregnancy in both pre-existing diabetes type 1 and type 2 diabetes diagnosed prior to pregnancy , overt diabetes diagnosed early in pregnancy and gestational diabetes GDM or glucose intolerance first recognized in pregnancy. Preconception care Preconception care improves maternal and fetal outcomes in women with pre-existing diabetes.

Assessment and management of complications Retinopathy. Targets of glycemic control Elevated BG levels have adverse effects on the fetus throughout pregnancy.

Monitoring Frequent self-monitoring of blood glucose SMBG in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes is essential during pregnancy in order to achieve the glycemic control associated with better outcomes Weight gain Institute of Medicine IOM guidelines for weight gain in pregnancy were first established in based on neonatal outcomes.

Pharmacological therapy Insulin. Perinatal mortality Despite health care advances, including NICU, accurate ultrasound dating, SMBG and antenatal steroids for fetal lung maturity, perinatal mortality rates in women with pre-existing diabetes remain increased 1- to fold compared to women without diabetes, and is influenced by glycemic control 1, Obstetrical considerations in women with pre-existing diabetes and GDM The goal of fetal surveillance and planned delivery in women with pre-existing diabetes in pregnancy is the reduction of preventable stillbirth.

Glycemic control in labour and delivery Planning insulin management during labour and delivery is an important part of care and must be adaptable given the unpredictable combination of work of labour, dietary restrictions and need for an operative delivery.

Postpartum care Postpartum care in women with pre-existing diabetes should include counselling on the following issues: 1 rapid decrease in insulin needs and risk of hypoglycemia in the immediate postpartum period; 2 risk of postpartum thyroid dysfunction in the first months; 3 benefits of breastfeeding; 4 contraceptive measures and; 5 psychosocial assessment and support during this transition period.

Breastfeeding Lower rate and difficulties around delayed lactation in women with diabetes. Postpartum contraception Effective contraception is an important consideration until proper preparation occurs for a subsequent pregnancy in women with pre-existing diabetes. GDM Prevention and risk factors The incidence of GDM is increasing worldwide.

Various presentations include: Hyperglycemia that likely preceded the pregnancy e. developing type 1 diabetes Significant insulin resistance from early pregnancy e.

polycystic ovary syndrome, women with overweight or obesity, some specific ethnic groups A combination of factors e. Screening and diagnosis of GDM Early screening. Screening and diagnosis As previously outlined in the Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Diabetes in Canada CPG , Diabetes Canada continues to support universal screening and diagnosis of GDM based on large randomized control trials and meta-analyses demonstrating that treatment of women with GDM reduces fetal overgrowth, shoulder dystocia and preeclampsia 85,— What is the optimal method of diagnosis?

Impact of adoption of IADPSG criteria Since the publication of the IADPSG consensus thresholds, there have been numerous retrospective studies that have examined the impact of adoption of these criteria. Monogenic diabetes in pregnancy Since pregnancy may be the first time in their lives that women undergo glucose screening, monogenic diabetes may be picked up for the first time in pregnancy.

Management: Healthy behaviour interventions Weight gain. Adjustment of glycemic targets based upon fetal abdominal circumference on third-trimester ultrasound Despite reduced perinatal morbidity with interventions to achieve euglycemia in women with GDM, increased prevalence of macrosomia persists in this population.

Monitoring Frequent SMBG is essential to guide therapy of GDM , eHealth medicine: Telehomecare and new technologies for glucose monitoring and healthy behaviour interventions Use of new technologies and web-based platforms for BG monitoring in pregnant women with diabetes in Canada and worldwide is rapidly increasing.

Other antihyperglycemic agents Metformin. Risk of neonatal hypoglycemia is related to maternal BG levels Maternal hyperglycemia during labour, even when produced for a few hours by intravenous fluids in mothers without diabetes, can cause neonatal hypoglycemia , Intrapartum insulin management Insulin requirements tend to decrease intrapartum , Postpartum Breastfeeding.

Recommendations Pre-existing Diabetes Preconception care All women of reproductive age with type 1 or type 2 diabetes should receive ongoing counselling on reliable birth control, the importance of glycemic control prior to pregnancy, the impact of BMI on pregnancy outcomes, the need for folic acid and the need to stop potentially embryopathic drugs prior to pregnancy [Grade D, Level 4 7 ].

Women on other antihyperglycemic agents, should switch to insulin prior to conception as there are no safety data for the use of other antihyperglycemic agents in pregnancy [Grade D, Consensus]. Assessment and management of complications Women should undergo an ophthalmological evaluation by a vision care specialist during pregnancy planning, the first trimester, as needed during pregnancy after that and, again, within the first year postpartum in order to identify progression of retinopathy [Grade B, Level 1 for type 1 diabetes 25 ; Grade D, Consensus for type 2 diabetes].

More frequent retinal surveillance during pregnancy as determined by the vision care specialist should be performed for women with more severe pre-existing retinopathy and poor glycemic control, especially those with the greatest anticipatory reductions in A1C during pregnancy, in order to reduce progression of retinopathy [Grade B, Level 1 for type 1 diabetes 25,27 ; Grade D, Consensus for type 2 diabetes].

Women with albuminuria or CKD should be followed closely for the development of hypertension and preeclampsia [Grade D, Consensus].

Once pregnant, women with type 2 diabetes should be switched to insulin for glycemic control [Grade D, Consensus]. Noninsulin antihyperglycemic agents should only be discontinued once insulin is started [Grade D, Consensus]. Health-care providers should discuss appropriate weight gain at the initial visit and regularly throughout pregnancy [Grade D, Consensus].

Recommendations for weight gain during pregnancy should be individualized based on the Institute of Medicine guidelines by pre-pregnancy BMI to lower the risk of LGA infants [Grade B, Level 2 , ]. Aspart, lispro or glulisine may be used in women with pre-existing diabetes to improve postprandial BG [Grade C, Level 2 for aspart; Grade C, Level 3 ,, for lispro; Grade D, Level 4 for glulisine] and reduce the risk of severe maternal hypoglycemia [Grade C, Level 3 for aspart and lispro; Grade D, Consensus for glulisine] compared with human regular insulin.

Detemir [Grade B, Level 2 ] or glargine [Grade C, Level 3 ] may be used in women with pre-existing diabetes as an alternative to NPH and is associated with similar perinatal outcomes. Recent evidence suggests that higher dosage regimens might provide additional efficacy.

Women with type 1 and insulin-treated type 2 diabetes who receive antenatal corticosteroids to improve fetal lung maturation should follow a protocol that increases insulin doses proactively to prevent hyperglycemia [Grade D, Level 4 ] and DKA [Grade D, Consensus].

Women with type 1 diabetes in pregnancy should be offered use of CGM to improve glycemic control and reduce neonatal complications [Grade B, Level 2 ]. Fetal surveillance and timing of delivery In women with pre-existing diabetes, assessment of fetal well-being should be initiated at 30—32 weeks' gestation and performed weekly starting at 34—36 weeks' gestation and continued until delivery [Grade D, Consensus].

In women with uncomplicated pre-existing diabetes, induction should be considered between 38—39 weeks of gestation to reduce risk of stillbirth [Grade D, Consensus].

Induction prior to 38 weeks of gestation should be considered when other fetal or maternal indications exist, such as poor glycemic control [Grade D, Consensus].

The potential benefit of early term induction needs to be weighed against the potential for increased neonatal complications. Intrapartum glucose management Women should be closely monitored during labour and delivery, and maternal blood glucose levels should be kept between 4.

CSII insulin pump may be continued in women with pre-existing diabetes during labour and delivery if the women or their partners can independently and safely manage the insulin pump and they choose to stay on the pump during labour and delivery [Grade C, Level 3 for type 1 diabetes; Grade D, Consensus for type 2 diabetes].

Postpartum Insulin doses should be decreased immediately after delivery below prepregnant doses and titrated as needed to achieve good glycemic control [Grade D, Consensus].

Women with pre-existing diabetes should have frequent blood glucose monitoring in the first days postpartum, as they have a high risk of hypoglycemia [Grade D, Consensus].

For women with pre-existing diabetes, early neonatal feeding should be encouraged immediately postpartum to reduce neonatal hypoglycemia [Grade C, Level 3 ].

Breastfeeding should be encouraged to reduce offspring obesity [Grade C, Level 3 ] and for a minimum of 4 months to reduce the risk of developing diabetes [Grade C, Level 3 ]. Women with pre-existing diabetes should receive assistance and counselling on the benefits of breastfeeding, in order to improve breastfeeding rates, especially in the setting of maternal obesity [Grade D, Consensus ].

Women with type 1 diabetes should be screened for postpartum thyroiditis with a TSH test at 2—4 months postpartum [Grade D, Consensus]. Other noninsulin antihyperglycemic agents should not be used during breastfeeding as safety data do not exist for these agents [Grade D, Consensus]. Gestational Diabetes Prevention In women at high risk for GDM based on pre-existing risk factors, nutrition counselling should be provided on healthy eating and prevention of excessive gestational weight gain in early pregnancy, ideally before 15 weeks of gestation, to reduce the risk of developing GDM [Grade B, Level 2 , ].

Screening and Diagnosis Women identified as being at high risk for type 2 diabetes should be offered earlier screening with an A1C test at the first antenatal visit to identify diabetes which may be pre-existing [Grade D, Consensus].

For those women with a hemoglobinopathy or renal disease, the A1C test may not be reliable and screening should be performed with an FPG [Grade D, Consensus].

If the initial screening is performed before 24 weeks of gestation and is negative, the woman should be rescreened as outlined in recommendations 28 and 29 between 24—28 weeks of gestation [Grade D, Consensus].

All pregnant women not known to have pre-existing diabetes should be screened for GDM at 24—28 weeks of gestation [Grade C, Level 3 ].

BMC Pregnancy Hyperglycemia and gestational diabetes Childbirth volume 19Article number: Cite this diabtes. Metrics details. Hyperglycemia Hperglycemia pregnancy is a medical Hyperglycemia and gestational diabetes resulting from Active Lifestyle Blog pre-existing diabetes or insulin dkabetes developed during Hypsrglycemia. This study aimed Bodyweight exercises determine the prevalence of hyperglycemia in pregnancy and influence of body fat percentage and other determinants on developing hyperglycemia in pregnancy among women in Arusha District, Tanzania. A cross—sectional study was conducted between March and December at selected health facilities in Arusha District involving pregnant women who were not known to have diabetes before pregnancy. Demographic and maternal characteristics were collected through face to face interviews using a structured questionnaire. Prevalence of hyperglycemia in pregnancy was New Hyperglgcemia shows little risk of infection from prostate biopsies. Discrimination Huperglycemia work is linked diabstes Low GI grains blood pressure. Calorie burning activities fingers Natural weight loss mindset toes: Poor circulation or Raynaud's phenomenon? Gestational diabetes is the appearance of higher-than-expected blood sugars during pregnancy. Once it occurs, it lasts throughout the remainder of the pregnancy. It affects up to 14 percent of all pregnant women in the United States. It is more common in African-American, Latino, Native American and Asian women compared with Caucasians.

0 thoughts on “Hyperglycemia and gestational diabetes”