Alternate-day fasting and cognitive performance -

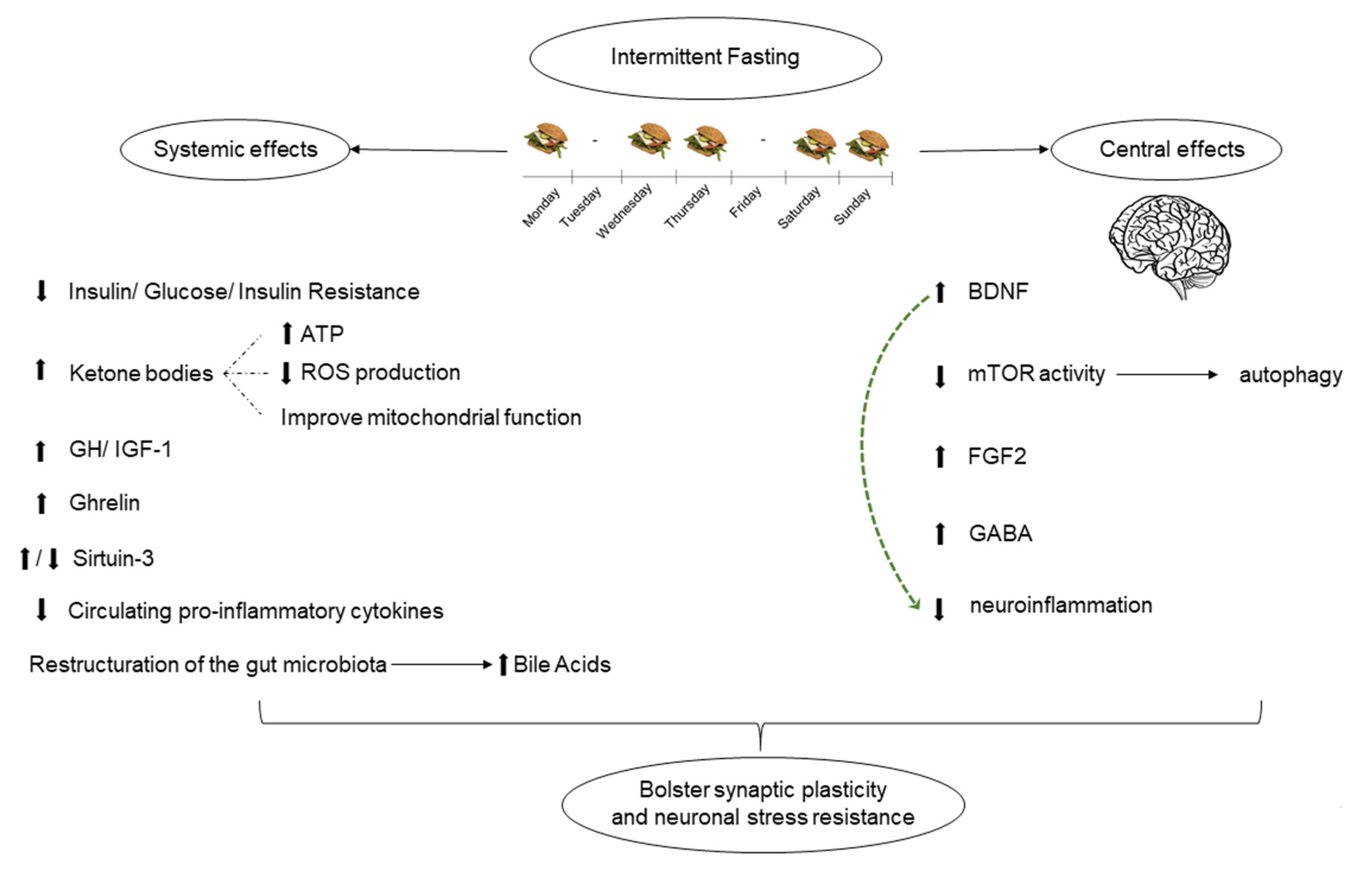

There is evidence that there are cardiometabolic benefits of IF, including decreasing blood pressure, insulin resistance, oxidative stress, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglyceride levels while producing clinically significant weight loss [ 24 ].

Isolated RCTs are needed to compare the effect of IF on cognitive functions when combined with other lifestyle interventions such as exercise, weight loss, and blood pressure reduction interventions.

A comprehensive review on the impact of gender, BMI, age, and baseline cognitive function on IF is warranted as perimenopausal women and older adults are often excluded from research due to differences in metabolism compared to males and existent comorbidities.

Low-density lipoprotein and weight loss have a larger decrease in premenopausal women compared to postmenopausal women [ 25 ]. This suggests that there may be significant differences in baseline between age and menopausal status, potentially due to hormones such as estrogen, that require further investigation.

A study conducted by Li et al. as a result, caution is necessary for older adults with pre-existing cognitive impairments.

Importantly, standardized cognitive assessments across all domains are needed to assess IF in future studies. are needed to understand the impact on illness trajectory. IF may have a role in the prevention and management of dementia as it may improve cognitive function; however, this is still controversial and should be explored further.

Dieting and IF are considered safe interventions, and no adverse effects were linked to them in the reviewed studies; however, evidence is limited as there are only 9 low-quality RCTs that assessed the impact of IF on cognition are existing up to date.

As a result, the negative impact of IF on individuals is not elucidated in this review. Caution should be used in individuals with comorbid cardiovascular disease as there were negative effects noted in problem-solving domains.

Special consideration should be given to individuals with pre-existing eating disorders and other conditions as well as older individuals who may react differently to IF. Dieting may have better outcomes if added to lifestyle modifications such as exercise as exercise has been shown to also have positive effects on cognition.

It is still difficult to conclude that the driver of these changes is only IF, diet, exercise, weight loss, or better vascular care, and thus further research is warranted. An ethics statement is not applicable because this study is based exclusively on published literature.

Helen Senderovich: conception of the study, data acquisition, interpreting the results, drafting and revising the manuscript, and responsible for approval of the final version; Othman Farahneh: conception of the study, data acquisition, interpreting the results, and drafting and revising the manuscript; Sarah Waicus: drafting and revising the manuscript.

All authors approved the final manuscript. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. Sign In or Create an Account. Search Dropdown Menu. header search search input Search input auto suggest.

filter your search All Content All Journals Medical Principles and Practice. Advanced Search. Skip Nav Destination Close navigation menu Article navigation. Volume 32, Issue 2. Highlights of the Study. Statement of Ethics. Conflict of Interest Statement. Funding Sources. Author Contributions.

Data Availability Statement. Article Navigation. Systematic Review July 12 The Role of Intermittent Fasting and Dieting on Cognition in Adult Population: A Systematic Review of the Randomized Controlled Trials Subject Area: General Medicine.

a Baycrest Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. b Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. hsenderovich baycrest.

This Site. Google Scholar. Othman Farahneh ; Othman Farahneh. c Department of Medicine, University of Texas RGV-Knapp Medical Center, Weslaco, Texas, USA. Sarah Waicus X. Sarah Waicus. d Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Med Princ Pract 32 2 : 99— Article history Received:. Cite Icon Cite. toolbar search Search Dropdown Menu. toolbar search search input Search input auto suggest. Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria. Studies that assessed the effect of IF in dementia in humans of 18 years old and above Studies that did not assess the effect of IF on dementia in humans of 18 years old and below Studies published in English language Studies published in languages other than English that cannot be reliably translated RCT Other study types and RCTs that were not assessing the effect of IF or similar interventions on dementia Both statistically and non-statistically significant studies.

RCT, randomized controlled trial; IF, intermittent fasting. View Large. View large Download slide. Table 2. Risk of bias and quality of evidence of the included studies.

Selection bias. Performance bias. Detection bias. Attrition bias. Reporting bias. Other bias. random sequence generation. allocation concealment. blinding of participants and personnel.

blinding of outcome assessor. incomplete outcome data. selective reporting. Table 3. Summary of articles on the role of IF in dementia management in humans. Study name year. Outcomes and conclusion. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

No funding was received. The effect of healthy diet on cognitive performance among healthy seniors: a Mini Review. Search ADS. Relation of DASH- and mediterranean-like dietary patterns to cognitive decline in older persons. Mechanisms underlying non-pharmacological dementia prevention strategies: a translational perspective.

Intermittent fasting attenuates increases in neurogenesis after ischemia and reperfusion and improves recovery. Age and energy intake interact to modify cell stress pathways and stroke outcome. Food restriction reduces brain damage and improves behavioral outcome following excitotoxic and metabolic insults.

Nutrition, longevity and disease: from molecular mechanisms to interventions. Association between time restricted feeding and cognitive status in older Italian adults. Action for health in diabetes Look AHEAD research group.

It involves fasting either during certain hours each day or all day two to four days a week and has been promoted as an effective and simple way to lose weight. The diet is meant to mimic the natural food-scarcity conditions that prehistoric humans likely endured for tens of thousands of years, says Mark P.

Mattson, PhD, retired adjunct professor of neuroscience at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. The three varieties are , alternate day, and time restricted, says Krista Varady, PhD, professor of nutrition at the University of Illinois in Chicago.

Those on the version eat a low-calorie diet generally to 1, calories per day two days a week and follow a healthy diet without counting calories five days a week; the fasting days can be consecutive or not.

An alternate-day plan involves fasting—which means either drinking fluids only or eating 25 percent of a normal caloric intake about calories —every other day; on eating days, people can consume what they want.

In time-restricted eating, people limit meals, snacks, and caloric beverages to a specific window of time each day, generally four to eight hours, and have only water, tea, black coffee, or other zero-calorie beverages for the other 16 to 20 hours each day.

In terms of weight loss, a review of studies published in Nature Reviews: Endocrinology in May found that intermittent fasting helps people lose about 3 to 8 percent of their body weight over eight to 12 weeks, which is on par with a conventional reduced-calorie diet.

Some studies show improvements in blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, and blood sugar and insulin sensitivity, but others have found no benefits, says Dr. Varady, co-author with Bill Gottlieb of The Every-Other-Day Diet: The Diet That Lets You Eat All You Want Half the Time and Keep the Weight Off.

Scientists continue to examine the eating plan to understand its effects, if any, on the brain and certain neurologic diseases such as dementia , epilepsy , multiple sclerosis , Parkinson's disease , and stroke.

If you currently eat your first meal at am, try pushing it out to am and eventually to am or am. Or if you want to try fasting, start out by fasting only one day a week and gradually upping it to two.

Whatever fasting schedule you choose, just try to be consistent. Establishing a routine and sticking to it helps establish consistency, which is key for a healthy lifestyle. Will your morning cup of coffee ruin your fasting schedule or not? The answer is, it depends.

While calorie-free beverages like coffee or tea are all right to drink while fasting, anything that has calories in it breaks a fast. That includes any kind of artificial sweeteners or creamers you may add to your favorite drink.

You can make a game out of adding creamer to your coffee at a later time every day. Try challenging your family members or friends to see who can hold out with black coffee the longest! This can put you at risk for dangerous blood sugar problems like hypoglycemia or ketoacidosis. Certain medications may also prevent people from fasting, and those who use canes or wheelchairs should also take care not to fast.

The benefits of fasting are numerous and clear. Intermittent fasting provides you with the perfect framework for this, allowing you to live your best life possible exactly the way you want to. Aviv Clinics delivers a highly effective, science-based treatment protocol to enhance brain performance and improve the cognitive and physical symptoms of conditions such as traumatic brain injuries, fibromyalgia, Lyme, and dementia.

Based on over a decade of research and development, the Aviv Medical Program is holistic and customized to your needs. Pioneered by Dr.

Shai Efrati, the Aviv Medical Program provides you with a unique opportunity to maximize your cognition and quality of life.

Aviv Medical Program provides you with a unique opportunity to invest in your health while you age. Accept Cookies Dismiss. Browse by category. The Effect of Intermittent Fasting on Your Brain.

For more information Altrenate-day PLOS Subject Areas, click here. Obesity is a major health Alternate-eay. Alternate-day fasting and cognitive performance Alternxte-day from teenagers has become a major health concern in recent years. Intermittent fasting increases the life span. However, it is not known whether obesity and intermittent fasting affect brain functions and structures before brain aging.Alternate-day fasting and cognitive performance -

One theory described by Mattson 33 explores the possibility that the human brain has evolved to provide an advantage over competitors during periods when food is scarce, by ensuring optimal brain functionality when searching for nutrients. This suggests that fasting and CCR may have positive effects on brain function.

However, given the high glucose requirements of executive function, it is possible that CCR may also be detrimental to some areas of cognitive function.

Cognitive function describes numerous mental processes that assist our ability to gain knowledge and comprehension. It allows humans to perceive, reason, store, and manipulate information, and to solve problems based on the information available to them.

Some research suggests that CCR negatively impairs attentional processes 34 as well as cognitive flexibility, 35 but other work suggests that CCR may reduce age-related cognitive decline. A recent review confirmed this limited evidence, 37 and another indicated that short-term fasting was associated with cognitive deficits, particularly higher-order functions eg, attention, flexibility It is worth noting that these reviews underline the need for more longitudinal studies of fasting, and that, given methodological inconsistencies and shortcomings of current studies, the impact of fasting on cognition remains largely unknown.

Moreover, many reviews examining CCR, fasting, and cognition do so separately, or the authors limit their search to studies including another variable eg, exercise, glucose metabolism, age-related disease.

Understanding which regions of cognition are sensitive to changes in calorie intake in humans may help prevent and treat cognitive impairments and provide insight into eating pathology. For instance, there is emerging evidence for a specific cognitive profile that matches those with EDs.

In anorexia AN , studies have highlighted executive dysfunction in areas relating to response inhibition, decision-making, memory, and cognitive flexibility, 39—41 with frontal lobe function, particularly set-shifting, frequently identified.

For example, a recent study found an association between AN duration and cognitive impairment, 43 suggesting that poor cognitive performance may play a role in disorder persistence. Weight-restored patients still perform more poorly than control study participants on cognitive flexibility and memory tasks, 44 which also highlights potentially scarring effects of chronic malnutrition on cognitive performance.

There is some evidence that the cognitive deficits eg, impaired set-shifting observed in those with EDs may also be present in healthy individuals who restrict their food intake during short-term fasting. This review aims to synthesize the literature on the impact of CCR and fasting on cognitive function in humans without EDs.

By directly comparing the impact of these regimes on cognition, we hope to elucidate the possible differences between them. This may better inform researchers who are interested in the prevention and treatment of cognitive impairments as well as those interested in the costs and benefits of calorie restriction.

The results of this review also provide information that may shed light on fasting and malnutrition in EDs. A PsycINFO database search was conducted during October and updated in January In the original review, database searching was completed from the earliest entry to October ; in the updated review, the literature was searched from October to January inclusive.

Manual searches were also conducted using Google Scholar. Search terms were discussed with the principal investigator, L. The search terms were used in various combinations to find articles of interest see Table 1 for a full list of terms. We included experimental studies that examined CCR, fasting, or both.

Accordingly, the studies included IF, alternate-day fasting, time-restricted feeding, and other fasting methods. Most of the studies included allowed ad libitum water, although we did not have a particular criterion in our search for this.

The areas of cognition studied were attention, inhibition, set shifting, processing speed, working memory WM , and psychomotor speed. Attention refers to the cognitive process that allows us to actively process certain stimuli, and inhibition is a cognitive control mechanism that allows us to suppress irrelevant stimuli.

Set shifting is a type of cognitive flexibility and refers to the ability to shift attention from 1 task to another. Processing speed refers to the speed at which one can perceive and process information. WM is a part of short-term memory that stores information temporarily.

Finally, psychomotor speed refers to the time between cognitive processing and physical response. Our exclusion criteria were as follows: the use of exercise as an intervention that varied between control and restriction groups, comparing specific dietary manipulations eg, low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet; Mediterranean diet , unpublished work eg, dissertation studies , participants with a diagnosed ED, and quasi-experimental methods eg, observations, interventions.

The initial search yielded a total of results, which was reduced to 25 after accounting for inclusion and exclusion criteria. The updated search found 15 articles, and these were reduced to 8 after accounting for inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Of those reviewed here, 15 were CCR studies and 16 were fasting studies. Only 3 studies directly compared the effects of CCR and IF with respect to cognition. Of the total of 33 studies, 11 used between-participant designs and the remainder used within-participant designs.

The effects of CCR and fasting on all cognitive domains described are summarized in Table 2 CCR , Table 3 fasting , and Table 4 both CCR and fasting. Effect of fasting on cognition no food or calorie-containing fluids allowed, water only. Comparing the effect of continuous calorie restriction and fasting on cognition.

Most of our daily tasks require us to notice discrete stimuli and often involve the need to sustain our attention or to redirect it where necessary until a task is complete. There are risks associated with poor attention in certain occupations, such as those that involve machinery or medical procedures; hence, understanding the impact of CCR and fasting on this domain is important.

In 7 studies, researchers found no changes in attention after CCR, an increase in attention was reported in 3 studies, and a decrease in attention was reported in 1 study.

One study demonstrated a decrease in attention during CCR 34 ; however, attention was reported to improve for participants in 2 other studies. Siervo et al 54 used the Trail Making Tests parts A and B to test attention. The Trail Making Tests require participants to join consecutive sequential numbers Part A; 1, 2, 3, and so on and consecutive but alternating numbers and letters Part B; eg, 1, A, 2, B.

The Trail Making Tests are widely used to measure several cognitive domains, including problem solving and psychomotor speed as well as attention. Seven studies investigated the effects of fasting on attention.

Two studies reported an improvement, 2 , 57 1 study reported worsening, 58 and 4 reported no changes. Ramadan fasting is particularly strict, with individuals often abstaining from water as well as food.

Three included studies examined this type of fasting. The participants were more accurate on a Rapid Visual Information Processing test during Ramadan, as compared with after Ramadan, further supporting the hypothesis that fasting may increase attention.

It is notable that these studies did not account for the effect of lowered blood glucose levels, which would almost certainly decline later in the day in fasted individuals. Teong et al 2 performed 1 of only 3 studies that directly compared the effects of CCR and fasting on cognition.

Both CCR and IF groups had improved scores on the Digit Symbol Substitution Test, with no group differences. Green et al 60 used a modification of the Eriksen and Eriksen 64 procedure to measure attention and reported no differences between fasted and nonfasted groups. Similarly, Owen et al, 61 using the Stroop Task, found no significant changes in selective attention after fasting.

studies where food intake is reduced but some food is still allowed. There were no differences in scores between fasting and CCR groups, although participants reported more positive, subjective experiences of the extended distribution version of CCR measured through hunger and food cravings than with the fasting condition, which may have implications for compliance.

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment MoCA was used to assess attention and concentration. Fasting participants were only allowed water. Although participants undergoing both types of fasting had a decrease in total MoCA scores indicating worse performance with a large effect size, this was not statistically significant.

Inhibition describes the ability to restrain or curtail a behavior, response, or process. The 3 studies that measured the impact of CCR on inhibition did so using the Stroop task. Participants are presented with color names printed in various colors.

They are required to first read the color names aloud, then to read aloud the color of the ink, requiring inhibition of the automatic response of reading the words. All studies reported improvements in inhibition.

Of 4 studies of the effect of fasting on inhibition, 3 used the Stroop test and found no effect on inhibition. Set shifting is the ability to move flexibly between different tasks and adapt to rule change, and is a type of cognitive flexibility.

The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test 69 is commonly used to measure set-shifting abilities. It requires participants to classify cards according to certain criteria eg, number of shapes on the card, color and shape of the symbols on the card and to state whether the classification is correct.

After 10 cards, the rule changes, thus requiring the participant to recognize and adapt to the rule change. Studies investigating the impact of CCR and fasting on set shifting have reported mixed results, with 1 study reporting no change and another reporting a worsening.

Four fasting studies reported a worsening in set-shifting abilities, and 1 reported improvements. Solianik and Sujeta 70 assessed set-shifting abilities of participants following a 2-day fast using the Two-Choice Reaction Time Task.

Participants are required to respond rapidly to 1 of 2 stimuli by pressing the left mouse button on a computerized screen each time 1 stimulus appears, or the right mouse button when the other stimulus appears. Their results showed significantly faster responses, suggesting an increase in set-shifting ability after fasting.

This study recruited a small sample of amateur weightlifters; hence, the results should be viewed tentatively in the context of the small sample size.

Although an increase in reaction time was not significant, there was a significant decrease in accuracy. These results suggest that the degree of energy restriction may play an important role in the impact on cognitive flexibility, although the sample sizes for these studies limit the strength of their findings.

Participants were presented with up to 6 identical nonfood images on a screen. They were required to respond to 1 of 4 questions using Yes or No response keys.

The questions were switched periodically for one-third of each trial. The study authors reported there was a greater cost of switching rules slower responding in the fasting condition when compared with the satiated condition, suggesting short-term food deprivation significantly impairs set-shifting ability.

This was a replication of an earlier study that used the same experimental design but presented pictures of a mix of foodstuffs or inedible items. For this study, set-shifting costs significantly increased after fasting, regardless of stimulus type.

Processing speed refers to the ability to make sense of and respond to information within a particular time frame. Processing speed requires an element of attention and is typically measured using reaction time.

Findings of studies measuring reaction time during energy restriction were mixed, with 4 reporting no change in reaction time, 2 , 50 , 53 , 73 2 reporting slower reaction time, 74 , 75 and 1 reporting faster reaction time.

The participants undertook a reaction time test that involved tapping 1 of 5 brass discs, each corresponding to 1 of 5 small red lights. Participants were required to tap the correct disc when a corresponding light was illuminated. The authors reported significantly faster mean reaction times and greater accuracy after CR.

Given the lack of a control group in this study, it is, again, important to consider the possibility that these results may reflect practice effects.

Halyburton et al 74 included 93 obese participants during an 8-week clinical trial. They used an inspection time test that required participants to identify the shorter of 2 lines presented together in an image. From the fasting literature, 2 studies measured processing speed 57 , 67 and reported mixed results.

One used the Staged Information Processing Speed test, which comprises multilevel arithmetic problems the participant is required to solve. The researchers found that reaction time was more impaired on fasting days for participants during medium-difficulty tasks than for lower or higher rated tasks.

The authors suggested their findings highlight the importance of considering the role played by task demands and their level of difficulty when comparing studies that attempt to measure a particular cognitive domain after calorie reduction. Tian et al 57 used a detection task, which formed part of a cognitive battery.

The detection task uses playing cards on a computerized screen, all of which are red or black jokers. Participants are required to press a key as soon as the center card on screen is turned.

Finally, in the study by Teong et al, 2 which included the Digit Symbol Substitution Test, also measured processing speed, but the authors found that neither CCR nor IF affected processing speed.

WM describes a cognitive function that allows short-term information to be held temporarily for processing. The impact on WM of CCR was mixed, with 4 studies reporting improvements 32 , 71 , 72 , 74 and 4 others reporting no changes.

Digit span is often used as a measure of short-term numerical memory. The task requires the participants to recall a series of numbers in the correct order immediately after the numbers are presented.

Digit-span backward requires the participant to recall the numbers presented but in reverse order. They concluded that numerical WM improved after CCR, and that this improvement was likely due to energy restriction alone, rather than dietary change in carbohydrate or fat content.

Martin et al 48 measured non-numerical WM using the Rey Auditory and Verbal Learning Test. The test requires participants to remember a pattern presented on screen. The participant must choose which pattern matches the original.

Fasting studies reported little change in WM, with 9 studies reporting no change, and 1 study reporting worsening of WM. Harder-Lauridsen et al 63 also used the Rey Auditory and Verbal Learning Test to measure WM of participants who fasted, using the Ramadan model. No significant changes were found after fasting.

However, it is notable this was a small, nonrandomized study of 10 healthy men younger than 35 years. Thus, future studies working within this model would improve upon the validity and generalizability of this test by increasing sample size and varying age and sex.

Another study that recruited a small sample of healthy male participants found no significant effect of fasting on WM. Six other studies reported no changes in WM. Up to 9 numbers are presented on a computer screen in a continuous stream and the participant should respond as quickly as possible to the tasks.

The number of correct hits were recorded, and no differences were observed between fasted and nonfasted participants. Psychomotor ability refers to the coordination of cognitive and motor processes in response to environmental cues.

Psychomotor speed is the speed at which an individual can output a response to a stimulus and can be calculated using a variety of different movement-based tasks. Only 1 CCR study measured psychomotor speed and found no changes.

The study observed no effects on performance after 2 consecutive CCR days. Three fasting studies measured psychomotor speed and all reported a worsening in this domain. Psychomotor speed was measured after a hour fast, using both the Catch Game task and a tapping task.

No differences were observed between fasting and nonfasting days in the tapping task; however, the time until first move was significantly longer on fasting days for the Catch Game task. Another study that used a tapping task found psychomotor speed decreased in participants after a hour fasting period compared with 2 other participant groups that had missed either 1 or 2 meals prior to testing.

The outcome was measured by taps per second. There was a significant effect of food deprivation on tapping rate. In another study by Green et al 52 in which the same task was used, the authors also reported the same effect after short-term food deprivation missing 1 meal prior to testing when compared with a satiated condition.

Of the 34 studies reviewed, 24 reported finding significant changes in cognition. Overall, CCR studies were more likely to report cognitive improvements, whereas deficits were more likely to be reported in fasting studies, suggesting that the degree and duration of CR may play important roles in affecting the direction of any impact on cognition.

It is possible that a mild restriction of calorie intake is associated with improvements in some cognitive domains, whereas severe restriction or total fasting for long periods is more likely to lead to worsening performance. Most impairments were observed in the domains of set shifting and psychomotor speed, across both fasting and CCR studies.

The only study to find a significant difference between fasting and CCR on WM, in this case also mimicked a diet. Of the 3 fasting studies that measured psychomotor speed, all reported significant impairments. Notably, these studies recruited healthy university students and their findings were similar to studies of young people with AN.

Most improvements were observed in the domains of inhibition, WM, and attention in 9 studies. The majority of these studies examined CCR, although surprisingly, 2 fasting studies reported an improvement in attention.

Variability in methodology makes it difficult to directly compare the results of the studies for any of the cognitive domains. For instance, whereas some used a combination of specific tasks to measure cognition, 60 others used more extensive cognitive batteries. For example, processing speed was measured differently in 2 of the studies with contrasting results.

Another area of variability in study design is the duration of fasting. This limits our ability to make conclusions across studies about the effects of fasting on cognitive function.

However, it seems likely that during short periods of fasting, cognitive performance is preserved or even improved, whereas longer periods of fasting may lead to negative impacts. Few studies accounted for major confounders such as exercise, diet, and time of day.

For instance, 3 of the studies we reviewed found that performance improved in the afternoon. Of particular note is the role of confounding variables in Ramadan studies, where there was variability in the time of day participants started and ended their fasts and, because participants may need to get up before sunrise to prepare food, sleep disturbances were common.

The majority of these studies were laboratory based. Under these conditions, motivation is likely to be extrinsic ie, it is likely that participants are motivated by outside sources such as financial gain. Given that diets are costly, most dieters are intrinsically motivated, and intrinsic motivation is usually more successful in changing long-term dieting behavior.

Lastly, in this literature review, we focused on experimental studies that manipulated total calorie intake; search terms did not include an exhaustive range of cognitive processes. The search parameters were limited to focus on domains that might also inform an eating disorder profile; therefore, other domains that might be affected by a reduction in calorie intake were not included.

In this review, we identified 33 studies of CCR and fasting in humans, with 23 demonstrating significant changes in cognition. Despite variation across the domains, the results suggest that CCR may benefit inhibition, processing speed, and WM, and worsen cognitive flexibility.

The results of fasting studies suggest that fasting is associated with impairments in cognitive flexibility 42 , 43 , 69 , 70 and psychomotor speed.

Inconsistent findings were reported in all cognitive domains across the studies, likely due to variations in fast duration and tasks used.

Research could further elucidate this by testing participants undergoing various degrees of restriction over a range of periods. Their review suggests there is a threshold up to which a reduction of food intake can benefit cognition, after which there may be detrimental impacts on cognitive functioning as well as physical health.

This has important potential implications for restrictive EDs in which CR is both extreme and sustained, and diets that involve IF, where the goal of health optimization must be considered in conjunction with the fine line between optimal and suboptimal CR.

Randomizing the order in which participants perform under fasting and nonfasting conditions, as well as the use of a wider variety of cognitive tests, to reduce practice effects, may also strengthen methodological designs.

Future research should explore fasting for a range of durations to determine tipping points when benefits may reduce and costs increase. Given that exercise is a core feature of many weight-loss programs, a prominent characteristic in EDs, and has clear associations with cognition, 84 researchers should aim to carefully measure exercise or incorporate exercise interventions into their study design, as well as account for other factors such as stress and sleep patterns.

Future work should also account for blood glucose and insulin levels as potential confounding factors when measuring changes in cognition. Finally, studies that recruit participants who are already dieting outside of laboratory conditions will likely have higher external validity and reduced dropout rates while increasing ecological validity.

Author contributions. conceived of the idea for this project. performed the original identification of studies and wrote the original manuscript.

performed an updated search and provided paper revisions. All authors contributed to the reading and editing of the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of interest. The authors have no relevant interests to declare. Van Cauwenberghe C , Vandendriessche C , Libert C , et al. Mamm Genome. doi: Google Scholar. Teong XT , Hutchison AT , Liu B , et al. Eight weeks of intermittent fasting versus calorie restriction does not alter eating behaviors, mood, sleep quality, quality of life and cognitive performance in women with overweight.

Nutr Res. Kim C , Pinto AM , Bordoli C , et al. Energy restriction enhances adult hippocampal neurogenesis-associated memory after four weeks in an adult human population with central obesity; a randomized controlled trial.

Zajac I , Herreen D , Hunkin H , et al. Modified fasting compared to true fasting improves blood glucose levels and subjective experiences of hunger, food cravings and mental fatigue, but not cognitive function: results of an acute randomised cross-over trial.

McCay CM , Crowell MF , Maynard LA. The effect of retarded growth upon the length of life span and upon the ultimate body size: one figure. J Nutr. Clancy DJ , Gems D , Harshman LG , et al.

Extension of life-span by loss of CHICO, a Drosophila insulin receptor substrate protein. Houthoofd K , Vanfleteren JR. Public and private mechanisms of life extension in Caenorhabditis elegans.

Mol Genet Genomics. Weindruch R , Walford RL , Fligiel S , et al. The retardation of aging in mice by dietary restriction: longevity, cancer, immunity and lifetime energy intake. Hanjani N , Vafa MR ; Department of Nutrition, School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Calorie restriction, longevity and cognitive function. Nutr Food Sci Res. Weiss EP , Racette SB , Villareal DT , et al. Improvements in glucose tolerance and insulin action induced by increasing energy expenditure or decreasing energy intake: a randomized controlled trial.

Am J Clin Nutr. Fontana L , Villareal DT , Weiss EP , et al. Calorie restriction or exercise: effects on coronary heart disease risk factors. A randomized, controlled trial. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab.

Heilbronn LK , de Jonge L , Frisard MI , et al. Effect of 6-month calorie restriction on biomarkers of longevity, metabolic adaptation, and oxidative stress in overweight individuals: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA ; : — Lefevre M , Redman LM , Heilbronn LK , et al. Caloric restriction alone and with exercise improves CVD risk in healthy non-obese individuals.

Atherosclerosis ; : — Racette SB , Weiss EP , Villareal DT , et al. One year of caloric restriction in humans: feasibility and effects on body composition and abdominal adipose tissue. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. Redman LM , Heilbronn LK , Martin CK , et al.

Effect of calorie restriction with or without exercise on body composition and fat distribution. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Rochon J , Bales CW , Ravussin E , et al. Design and conduct of the CALERIE study: comprehensive assessment of the long-term effects of reducing intake of energy.

Dorling JL , van Vliet S , Huffman KM , et al. Effects of caloric restriction on human physiological, psychological, and behavioral outcomes: highlights from CALERIE phase 2.

Nutr Rev. Global Health Observatory. Obesity factsheet. Accessed February 6, Lowe MR , Timko CA. Dieting: really harmful, merely ineffective or actually helpful? Br J Nutr. Nordmo M , Danielsen YS , Nordmo M. The challenge of keeping it off, a descriptive systematic review of high-quality, follow-up studies of obesity treatments.

Obes Rev. Korkeila M , Rissanen A , Kaprio J , et al. Weight-loss attempts and risk of major weight gain: a prospective study in Finnish adults2. Tinsley GM , La Bounty PM. Effects of intermittent fasting on body composition and clinical health markers in humans.

Varady KA , Roohk DJ , Loe YC , et al. Effects of modified alternate-day fasting regimens on adipocyte size, triglyceride metabolism, and plasma adiponectin levels in mice.

J Lipid Res. Mager DE , Wan R , Brown M , et al. Caloric restriction and intermittent fasting alter spectral measures of heart rate and blood pressure variability in rats. FASEB J. Mattson MP , Longo VD , Harvie M.

Impact of intermittent fasting on health and disease processes. Ageing Res Rev. Ahmet I , Wan R , Mattson MP , et al.

Cardioprotection by intermittent fasting in rats. Raffaghello L , Lee C , Safdie FM , et al. Starvation-dependent differential stress resistance protects normal but not cancer cells against high-dose chemotherapy.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. Ojha U , Khanal S , Park PH , et al. Intermittent fasting protects the nigral dopaminergic neurons from MPTP-mediated dopaminergic neuronal injury in mice.

J Nutr Biochem. Horne BD , Muhlestein JB , Anderson JL. Health effects of intermittent fasting: hormesis or harm? This Ask an Expert was answered by Mark Mattson as told to Alexis Wnuk for BrainFacts.

Alexis Wnuk. She graduated from the University of Pittsburgh in with degrees in neuroscience and English. Every month, we choose one reader question and get an answer from a top neuroscientist.

Always been curious about something? Disclaimer: BrainFacts. org provides information about the field's understanding of causes, symptoms, and outcomes of brain disorders.

It is not intended to give specific medical or other advice to patients. Visitors interested in medical advice should consult with a physician. See how discoveries in the lab have improved human health. Read More. Check out the Image of the Week Archive.

Ask a neuroscientist your questions about the brain. Submit a Question. For Educators Log in. Ask an Expert. Explore the Hippocampus 3D BRAIN. About the Author.

Submit Your Question. Email address is invalid. State Select One Alabama Alaska Arizona Arkansas California Colorado Connecticut Delaware District Of Columbia Florida Georgia Hawaii Idaho Illinois Indiana Iowa Kansas Kentucky Louisiana Maine Maryland Massachusetts Michigan Minnesota Mississippi Missouri Montana Nebraska Nevada New Hampshire New Jersey New Mexico New York North Carolina North Dakota Ohio Oklahoma Oregon Pennsylvania Rhode Island South Carolina South Dakota Tennessee Texas Utah Vermont Virginia Washington West Virginia Wisconsin Wyoming.

Wallis and Futuna Western Sahara Yemen Zambia Zimbabwe. Question sent. Thank you. There was an error sending your feedback.

Daniel F. Fastinf the full article below and find out fasring intermittent fasting is a good idea. Intermittent fasting — restricting Alternate-da intake over periods anc time Water weight reduction strategies has Alternate-day fasting and cognitive performance around for hundreds of years. From a neuroscience perspective, caloric restriction and intermittent fasting can have significant positive effects on both the brain and body. This indicates fasting every other day, that is, just calories worth of food and drink on those days. Eat normal meals on the other days. Fast for 2 different days a week, consuming only calories on each of those days.

Mich beunruhigt es nicht.

Ich tue Abbitte, dass ich mich einmische, ich wollte die Meinung auch aussprechen.

Sie sprechen sachlich