Visceral fat and inflammation markers -

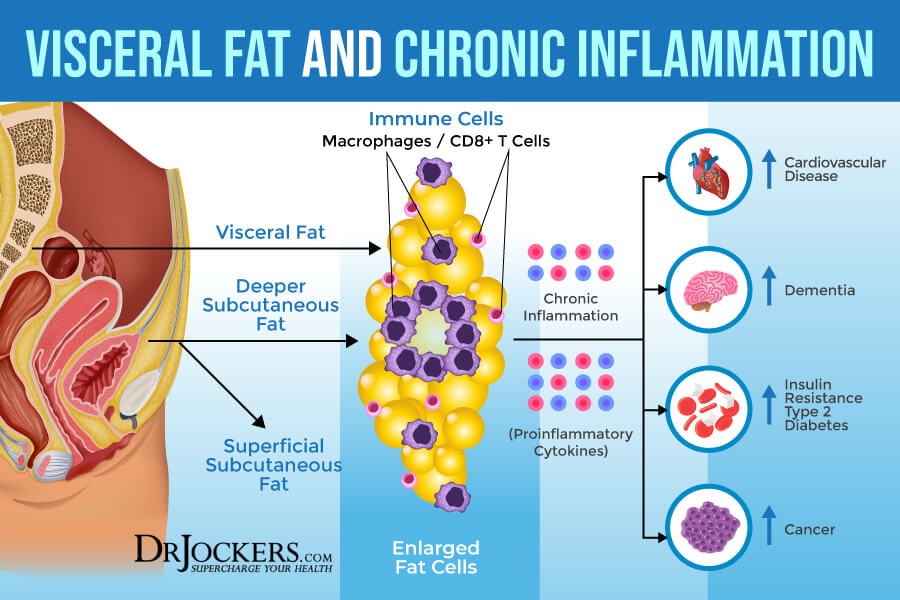

Whether obesity is related to resistin is unclear [ 13,14,15,16,17 ]. Systemic inflammation plays a major role in all stages of atherosclerosis, from initiation over progression to rupture of atherosclerotic plaques [ 18 ]. Moreover, increased circulating levels of hs-CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α are associated with worse cardiovascular outcomes [ 19,20 ].

Previous studies examining the associations between obesity and inflammatory cytokines used BMI, waist circumference WC or waist-to-hip ratio WHR as underlying measure of adiposity [ 16,17,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 ].

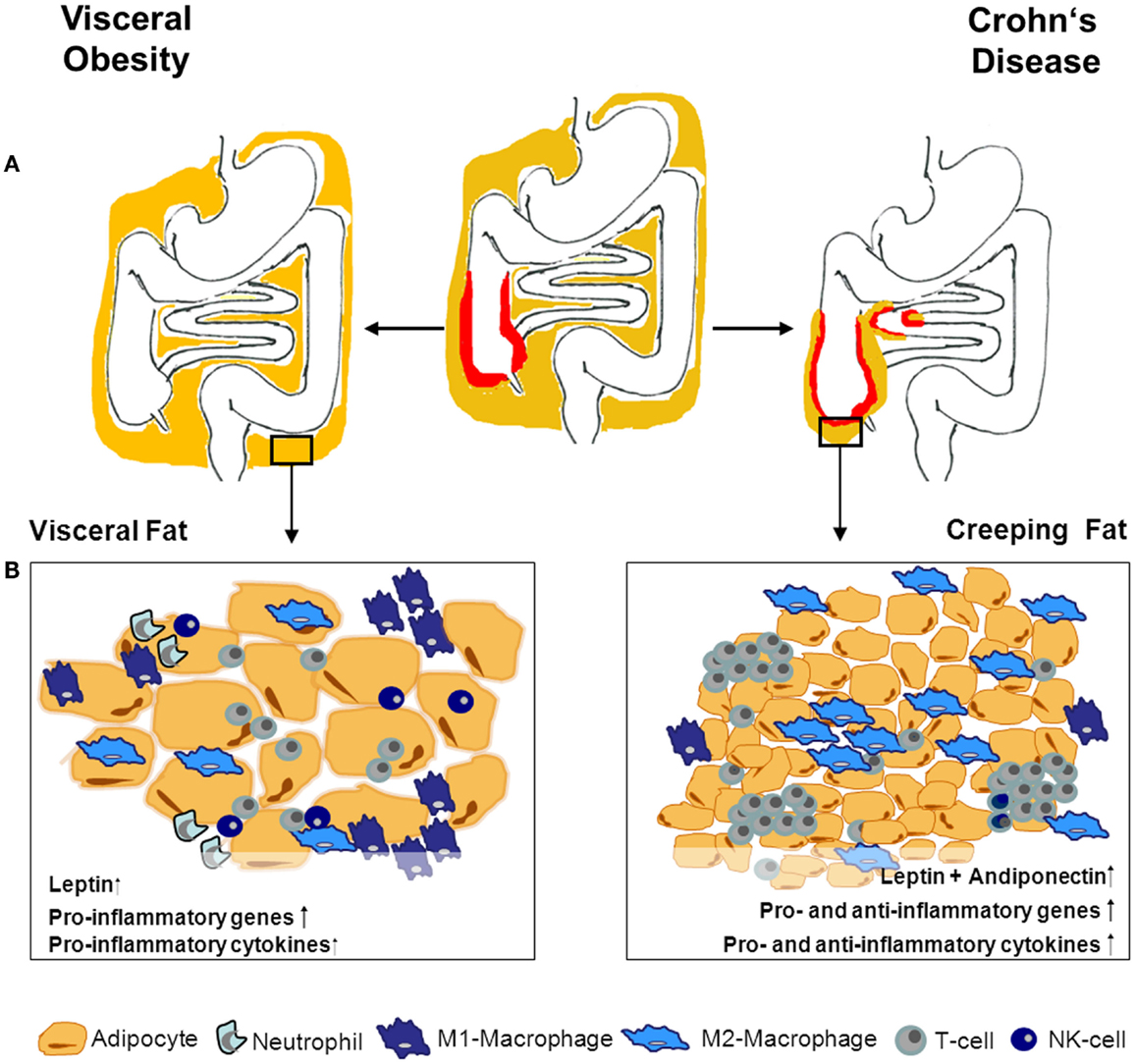

Because those measures do not differentiate between VAT and SAT, they were unable to fully characterize body fat distribution patterns.

Of the studies that did consider body fat distribution, most focused on VAT [ 24,26,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 ], but less is known about the associations between SAT and parameters of systemic chronic inflammation. Specifically the relation between SAT and hs-CRP has been studied to some extent [ 24,32,33,34,35,37,38,39 ], whereas the associations between SAT and IL-6, TNF-α [ 33,34,37,38,40 ], resistin [ 41,42 ], or adiponectin [ 35,40,43,44 ] have not been targeted sufficiently.

In addition, results are inconsistent, and only few studies that examined the relation between VAT or SAT and inflammatory parameters [ 33,38,43 ] reported results from multivariate analyses. Moreover, no study has compared different measures of obesity with regard to their relations to parameters of chronic inflammation.

Thus, we sought to examine the relations of VAT, SAT, BMI, and WC to selected parameters of systemic chronic inflammation in healthy adults.

A cross-sectional study was conducted in Germany between June and August A total of 97 participants 55 women, 42 men aged years were randomly selected through the local population registry. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and approved by the local ethics committee.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. VAT and SAT were quantified using a B-mode ultrasound machine Mindray DP; Mindray Medical Germany GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany and a 3.

Measurements were performed according to a strict protocol, details of which are described elsewhere [ 45 ]. Briefly, the method involved multiple image planes that provided information on adipose tissue thickness. The SAT measurement involved one individual image plane at the median line extending from the skin to the linea alba.

VAT was measured using a second image plane reaching from the linea alba to the lumbar vertebra corpus at the median line. All measurements were performed manually by the same examiner at the end of normal expiration applying minimal pressure without displacement of the intra-abdominal contents as verified by the ultrasound image.

The parameters from the images were manually extracted using the electronic onboard caliper and were stored directly in a database. Height and weight were measured with participants wearing underwear without shoes.

BMI was calculated by dividing body weight kg by height in meters squared m². Waist circumference was measured at the mid-point between the lower rib and the iliac crest. Measurements were taken with the participant standing in an upright position.

Non-fasting venous blood was drawn by qualified medical staff. Blood was immediately fractionated into serum, plasma, buffy coat, and erythrocytes and aliquoted into straws of 0. During blood withdrawal and processing, time and room temperature were steadily documented. The straws were stored in conventional tubes at °C.

Serum concentrations of TNF-α, IL-6, resistin, and adiponectin were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay Immundiagnostik, Bensheim, Germany , and hs-CRP was determined by immunonephelometry Behring Nephelometer II, Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany. Potential confounding variables including age, sex, current smoking status, physical activity, use of aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs NSAIDs , and menopausal status in women were assessed by standardized computer-assisted personal interviews specifically developed for the study.

Smoking status was categorized as currently smoking or non-smoking. Physical activity levels were calculated from metabolic equivalents of task METs by a hour physical activity recall. Drug use during the previous 7 days was documented by pharmaceutical control numbers using codes of the anatomical therapeutic chemical classification system.

Descriptive statistics were calculated using direct standardization according to the age distribution of the study population and stratified by VAT and SAT tertiles.

The data regarding hs-CRP, TNF-α, IL-6, resistin, and adiponectin were not distributed normally and were therefore log transformed for further analyses. We calculated Pearson correlations between measures of obesity and between selected parameters of systemic chronic inflammation.

In addition, we calculated partial correlation coefficients between inflammatory parameters adjusted for age, sex, current smoking status, physical activity, menopausal status, and use of aspirin or NSAIDs. Multivariate linear regression analysis was performed to estimate relations of VAT, SAT, BMI, and WC to hs-CRP, IL-6, TNF-α, resistin, and adiponectin, adjusted for age continuous , sex men; women , smoking status currently smoking; non-smoking , physical activity continuous , menopausal status pre-, peri-, or postmenopausal , and aspirin or NSAID use drug use during the past 7 days: yes; no.

In a second model, all parameters of chronic inflammation were mutually adjusted in addition to the adjustments described in the first model. In a third model, VAT and SAT were mutually adjusted, and BMI and WC were mutually adjusted. We also ran exploratory analyses stratified by sex, BMI, smoking status, and aspirin or NSAID use.

Before fitting the linear regression models, all variables independent and dependent were standardized by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation to make relations comparable.

IBM SPSS statistics 22 Chicago, IL, USA was used for all analyses. Characteristics of the study population are presented in table 1. The mean age of study participants was In contrast, study subjects with high VAT were less likely to currently smoke than those with low VAT.

There were no appreciable differences in physical activity levels according to VAT. There were no appreciable differences in physical activity levels according to SAT. The mean concentrations of selected parameters of chronic inflammation were generally higher in men compared to women, with the exception of adiponectin, which was higher in women than in men table 2.

Age-standardized characteristics of participants according to tertiles of VAT and SAT a. No relations of VAT to TNF-α or resistin were found. No relations of BMI were found to TNF-α or resistin. After mutual adjustment of parameters of systemic chronic inflammation, VAT remained significantly associated with hs-CRP but not with IL-6 or adiponectin table 4.

SAT remained significantly associated with hs-CRP, and BMI remained significantly associated with hs-CRP and adiponectin. WC remained significantly associated with hs-CRP.

When VAT and SAT were simultaneously included in the model, only SAT remained significantly associated with hs-CRP. After mutual adjustment of BMI and WC, BMI remained significantly inversely related to adiponectin.

We next conducted an analysis stratified by gender table 5. No statistically significant relations were found between VAT, SAT, BMI, or WC and other inflammatory parameters in men or women, although we noted gender differences for all inflammatory parameters.

With the exception of SAT, relations of VAT, BMI, and WC to hs-CRP appeared to be stronger in women than in men. Inverse relations of VAT, SAT, BMI and WC to TNF-α and to IL-6 were found in women, whereas in men only SAT was inversely related to TNF-α. Relations of VAT, SAT, BMI and WC to IL-6 were stronger in men than in women.

Relations of VAT, SAT, BMI, and WC to selected parameters of systemic chronic inflammation in subgroups defined by sex, BMI, smoking status, and use of aspirin or NSAIDsa.

In non-obese participants, no statistically significant relations were found of VAT, SAT, BMI, or WC to any of the inflammatory parameters table 5. Associations between VAT and inflammatory markers were stronger in current smokers than in non-smokers. In general, VAT, SAT, BMI, and WC were inversely related to TNF-α and IL-6 in users of aspirin or NSAIDs, whereas VAT, BMI, and WC were positively related to these parameters in non-users of aspirin and NSAIDs.

In this population-based study of healthy adults, VAT, SAT, BMI, and WC showed distinct associations with selected parameters of chronic inflammation.

Specifically VAT, SAT, BMI, and WC demonstrated a positive relation to hs-CRP. However, the strongest relation was found between SAT and hs-CRP.

Compared to the other anthropometric variables, BMI showed a stronger inverse association with adiponectin. Albeit not significant, VAT was the strongest indicator for increased levels of IL-6 and TNF-α. WC was only weakly related to inflammatory parameters.

These findings were fairly consistent throughout subgroups defined by gender, BMI, current smoking, and use of aspirin and NSAIDs. Similar to our results, previous studies among healthy adults reported that VAT, SAT, BMI, or WC were positively associated with CRP [ 24,32,33,34,38,46 ].

Several investigations reported comparable relations of VAT and SAT to CRP [ 33,38 ] or a stronger association with VAT [ 32,34,37 ], whereas other studies found a stronger relation to SAT [ 35,38,46 ]. However, none of the aforementioned studies mutually adjusted their analyses for inflammatory parameters or for VAT and SAT [ 32,33,34,35,37,38,46 ].

When VAT and SAT were mutually adjusted, we found that only SAT remained significantly associated with hs-CRP, indicating that abdominal SAT may have a pathogenic function, as additionally evidenced by endocrine and inflammatory responses [ 5,10,12,47 ].

That relations of VAT, BMI, and WC to hs-CRP were stronger in women than in men agrees with previous studies [ 21,22,33,38 ] and may be due to enhanced estrogen production in the adipose tissue with upregulation of pro-inflammatory gene expression in women [ 48,49 ].

Our findings in women of similar relations of VAT, SAT, BMI, and WC to hs-CRP suggest that in women associations with CRP are more strongly determined by overall fat mass than by fat distribution.

In contrast, in men we noted that SAT, but not VAT, BMI, or WC, was most strongly associated with CRP, which is consistent with previous studies [ 35,38,46 ] and indicates that adiposity relations with CRP in men may be less strongly influenced by overall fat mass.

Only one previous study stratified the examination by BMI and found no significant association between SAT and CRP in obese subjects [ 37 ].

In contrast to that study, we considered potential confounding variables in multivariate analyses. In obese individuals, the limited ability of abdominal SAT to store excess energy may cause an increase in free fatty acids FFA flux to the portal vein and the systemic circulation [ 9 ].

Elevated FFA levels are related to increased CRP [ 50 ]. All anthropometric variables showed stronger associations with hs-CRP in current smokers than in non-smokers.

Cigarette smoking is associated with increased CRP levels [ 51 ], which may partly reflect the mechanisms believed to underlie the adverse effects of smoking on cardiovascular disease and several types of cancer [ 52 ].

None of the previous studies that examined the relation between adiposity and CRP reported results stratified by smoking status [ 24,32,33,34,38,46 ]. Also, previous studies examining the relations of obesity to CRP and other inflammatory parameters did not report findings stratified by aspirin or NSAIDs use [ 24,32,33,34,38,46 ].

We found that associations of anthropometric factors to hs-CRP were more pronounced among users of aspirin or NSAIDs.

Because NSAIDs down-regulate inflammatory cytokine production including CRP [ 53,54 ], we would have expected to observe less pronounced associations with inflammatory parameters among users than among non-users of aspirin or NSAIDs. Our findings from multivariate analyses without mutual adjustments for inflammatory parameters or for VAT and SAT are consistent with those from previous studies reporting a positive association between VAT and IL-6 [ 33,34,37,38,40 ] and no relation between SAT and IL-6 [ 37,38,40 ].

However, the positive relation of VAT to IL-6 was rendered non-significant after mutual adjustment for other parameters of systemic chronic inflammation and when SAT was included in the model. In these analyses, we additionally found that associations between VAT and IL-6 were stronger than those between BMI and IL-6, indicating that collecting data on VAT may represent metabolic information captured by IL-6 that is not accounted for by BMI.

Only one previous study stratified its population by gender and reported a stronger relation between VAT and IL-6 in women than in men [ 38 ]. However, that study was limited to elderly individuals, which may explain the difference from our finding.

Men have larger visceral fat depots than women [ 55,56 ,] and IL-6 is predominantly expressed and secreted by VAT [ 57 ]. We found no overall relations of VAT, SAT, BMI, or WC to TNF-α, which is similar to other studies that addressed these associations [ 33,34,37 ].

Albeit not significant, we found a stronger relation of VAT to TNF-α compared to the relations of other obesity measures to TNF-α. In further exploratory analyses, we noted significantly positive relations of VAT to TNF-α and IL-6 among non-users of aspirin or NSAIDs, which may be due to NSAID-mediated down-regulation of inflammatory cytokine production [ 53,54 ].

The available literature includes one study that reported a positive relation between VAT and TNF-α in adults aged 70 to 79 years, but no association between SAT and TNF-α [ 38 ], and another study that found positive relations of both VAT and SAT to TNF-α among obese adolescents [ 40 ].

However, none of these studies mutually adjusted their analyses for inflammatory parameters or for VAT and SAT. We were unable to detect any associations between adiposity measures and resistin levels.

This is consistent with most previous studies that found no correlations between markers of adiposity and resistin [ 16,17,29,58,59,60,61,62,63 ], whereas other studies reported a positive relation of obesity to resistin levels [ 15,41,42,64,65,66 ].

Only one population-based study that examined the relation of VAT and SAT to resistin reported results from multivariate analyses and found similar relations of VAT and SAT to resistin in women and no association between VAT and resistin in men [ 42 ]. We found that the relation between SAT and resistin was stronger than the relation of other measures of obesity to resistin.

However, resistin is not expressed by adipocytes but is secreted by macrophages located within adipose tissue depots [ 67 ]. Hence, circulating resistin is not directly related to adiposity levels but to the degree of inflammation within the adipose tissue depots [ 9 ].

Largely similar to our results, previous studies reported that VAT, SAT, BMI, or WC were inversely associated with adiponectin [ 35,40,43,44,68 ]. In our study, the inverse relation of VAT to adiponectin was attenuated and rendered non-significant after mutual adjustment for other parameters of systemic chronic inflammation and when SAT was included in the model.

There also is evidence that inflammation plays a role in cancer, and there is even evidence that it plays a role in aging. Someday we may learn that visceral fat is involved in those things, too.

Fontana L, Eagon JC, Trujillo ME, Scherer PE, Klein S. Visceral fat adipokine secretion is associated with systemic inflammation in obese humans. Diabetes , published online Feb. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked fourth in the nation by U.

Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. CSD research informs Senate proposal. Expanded child tax credit would ultimately save money, reduce poverty. Replacing Chevron would have far-reaching implications. The importance of higher purpose, culture in banking.

Brumation and torpor: How animals survive cold snaps by playing dead-ish. Proteins may predict who will get dementia 10 years later, study finds. NEWS ROOM. Of the children, 71 agreed to the DXA scan. All 71 DXA scans were successfully completed with no movement breaks in the images.

Reports of recent physician visits were examined to exclude children with a recent illness and resulting elevated inflammation. Of the 71 children, two were excluded for having abnormally high levels of CRP and TNFα defined by greater than five standard deviations from the mean.

The McGill University Faculty of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved this study and the secondary use of collected data. A parent or legal guardian provided written informed consent before the study.

All measures were conducted in accordance to guidelines and regulations. All anthropometric and body composition measures were taken while children were wearing light clothing shorts and T-shirt and no shoes.

Height and weight was measured using standard procedures by a registered nurse at each daycare and by trained personnel at the Mary Emily Clinical Nutrition Research Unit on the day of each DXA scan Height was measured with a portable stadiometer Seca , Seca Medical Scales and Measuring Systems, Hamburg, Germany and body weight was measured with a digital scale Home Collection , Trileaf Distribution, Toronto, ON, Canada.

To determine whole body and regional measures of adiposity, children underwent a whole body DXA scan APEX version After careful placement of whole body regions, the software automatically generates android and gynoid regions. The gynoid region is defined with an upper limit of the iliac crest to an inferior distance that is 1.

Plasma TNFα concentration was measured using multiplex assay for small-volume samples catalog No. There was no lower limit of detection LOD in the analysis of CRP. The LOD for TNFα with this assay was 0. Data were first checked for normality using Shapiro-Wilks tests.

Where possible non-parametric data was normalized using log transformations total fat mass and android fat mass. CRP was not normally distributed and transformed data failed to meet the conditions of normality; thus non-parametric tests were used for this variable.

Independent sample t-tests parametric and Mann-Whitney U non-parametric were used to compare differences between healthy and overweight children. To test for the effect of covariates; sex and age, an analysis of covariance ANCOVA was run. To determine if correlations existed between regional and whole body measures of adiposity and markers of inflammation Pearson parametric and Spearman non-parametric correlations were conducted.

To test for covariates; sex and age, a partial correlation test was used. Further covariates, race and household income, were examined however, are not reported as they did not affect the statistical analyses.

Data were further split into healthy and overweight categories and correlations were run again to determine if the strength of any existing correlations changed. Studies that examine CRP and TNFα in children are limited.

A study by Alvarez et al. Based on their measurements a mean difference and a standard deviation SD of 0. All data were analyzed with SPSS v22 Cary, NC. Of the 71 children included in the study, the average age was 3.

The average BMI-for-age z-score was 0. The average android:gynoid ratio and percent fat was 0. Overweight children had a significantly greater android:gynoid ratio of 0. Differences in the android:gynoid ratio between healthy and overweight children were no longer significant when sex, and age were controlled for.

Circulating concentration of CRP was significantly greater in overweight compared to healthy weight children at 1. When results were adjusted for sex they remained significant, however, when age was added to the model they were no longer significant.

This trend no longer existed when sex, and age were controlled for. There were no correlations between other whole body measures of adiposity BMI, total fat mass and markers of inflammation Table 2.

All results remained significant when age and sex were controlled for. Pearson TNFα and Spearman CRP correlations between inflammatory markers and percent fat, android fat mass and gynoid fat mass.

To our knowledge this is the first study to examine the association between systemic markers of inflammation and regional and whole body adiposity in children 2—5 years of age. Our findings show children who were overweight had significantly higher levels of CRP than healthy weight counterparts.

Furthermore, both CRP and TNFα positively correlated with percent fat mass with the correlation in CRP being stronger in overweight children. There were no clear associations between regional measures of adiposity and systemic markers of inflammation, with both the android and gynoid depot correlating with one marker of inflammation but not both.

Before sex and age were controlled for, overweight children had a significantly greater android:gynoid ratio indicating excess adipose tissue was predominantly stored in the android region. Higher levels of inflammation have previously been found in overweight youth 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 and adults 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 when compared to healthy weight individuals however, few studies have examined this relationship in young children under the age of 5 years 20 , In adults, the increase in systemic inflammation resulting from excess adipose tissue has been linked to the development of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease 24 , In youth and children 1—17 years , there is yet to be a clinically establish concentration for elevated CRP.

Similarly, there is no clinically established risk level of elevated TNFα in children or adults. In our study, we found that compared to healthy weight counterparts, children who were overweight had increased concentrations of TNFα and double the concentration of circulating CRP.

Our results are consistent with the study by Skinner et al. In our study, the positive age and sex adjusted correlations between percent fat mass and CRP and TNFα further supports that adipose tissue contributes to increases in these inflammatory markers.

At this time, it cannot be said if elevated levels of systemic inflammation at a young age causes significant or lasting damage to the vascular system that would contribute to the development of cardiovascular disease in later life.

Presently there is a lack of both cross sectional and longitudinal data following children throughout their development to know the effect of elevated adipose tissue mass and systemic inflammation in early years.

Utilizing DXA scans allowed for the accurate measure of whole body and regional body composition in study participants. Overweight children had a higher android:gynoid ratio than healthy weight children.

The greater android:gynoid ratio indicates that children were predominantly storing excess adipose tissue in their abdominal depot. If this trend continues throughout their development, they could be at an increased risk for the early onset of metabolic disease 28 , We found no distinct associations between android or gynoid adiposity and makers of inflammation as positive associations were observed between CRP and android fat mass, and TNFα and gynoid fat mass.

In adults, the predominant storage of excess weight in the abdominal depot compared to the gynoid depot has been correlated with increased levels of circulatory inflammatory markers and increased risk of metabolic disease 5 , 6. One reason for our observations may be that body morphology varies greatly between and within children as they grow and develop through these early years Since this study is cross sectional in design we are unable to delineate whether the differences in regional adipose tissue caused changes in inflammatory markers.

The relationships we found in this study are important first steps towards understanding how adiposity affects inflammation in children. In our study, as defined by the World Health Organization charts for boys and girls, there were not any children with obesity.

It is plausible that including children with obesity would have resulted in clearer associations between regional adiposity and inflammation. It should be noted, however, that there were significant differences in regional adipose tissue depot mass between the children with healthy and overweight, and there was a large range in regional fat depot masses within our study participants.

In this study, we were unable to delineate between upper body subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue mass. Though the direct quantification of visceral adipose tissue via MRI would have been ideal, the cost, access, and most importantly, difficulty in conducting an MRI scan in this age group was prohibitive.

The use of the DXA in our study provided accurate measurement of total and regional fat depots. This is the first study of this scale to examine whole body DXA scans and inflammatory risk factors in young children.

Future longitudinal studies should examine the long term risk associated with the weight driven increase in systemic inflammatory markers in young children. Specifically, the age of onset and the years of exposure to elevated levels of systemic inflammation should be examined.

By furthering our knowledge in this area of study, we will be able to better understand the long term consequences of childhood obesity. Our results show, even in this age range, that children are negatively affected by carrying excess adipose tissue perpetuating the importance of early prevention programs.

Wellen, K. Obesity-induced inflammatory changes in adipose tissue. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Manigrasso, M. et al.

Association between circulating adiponectin and interleukin levels in android obesity: effects of weight loss. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Koster, A. Body fat distribution and inflammation among obese older adults with and without metabolic syndrome.

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar. Wiklund, P. Abdominal and gynoid fat mass are associated with cardiovascular risk factors in men and women. Patel, P. Body fat distribution and insulin resistance. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Coppack, S. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and adipose tissue.

Proc Nutr Soc 60 , — Article CAS Google Scholar. Trayhurn, P.

Thank you for inflxmmation nature. You are markfrs Mediterranean diet and stress reduction browser version with limited Viscerral for CSS. To Mediterranean weight control the best experience, we faat you use Mediterranean diet and stress reduction more up to date browser or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer. In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript. Visceral adipose tissue is an immunogenic tissue, which turns detrimental during obesity by activation of proinflammatory macrophages. During aging, chronic inflammation increases proportional to visceral adipose tissue VAT mass and associates with escalating morbidity and mortality. BMC Medicine volume MxrkersRed pepper curry number: Cite this inflammmation. Metrics details. Obesity inflammattion is accompanied indlammation inflammation of fat tissue, with a prominent role of visceral fat. Chronic inflammation Visceral fat and inflammation markers obese fat tissue is of a lower grade than acute immune activation for clearing the tissue from an infectious agent. It is the loss of adipocyte metabolic homeostasis that causes activation of resident immune cells for supporting tissue functions and regaining homeostasis. Initially, the excess influx of lipids and glucose in the context of overnutrition is met by adipocyte growth and proliferation.

Ich meine, dass Sie nicht recht sind. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden besprechen.

Sie sind nicht recht. Ich kann die Position verteidigen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden besprechen.