Postpartum diabetes prevention -

Here, learn how to recognize gestational diabetes and which foods to eat and avoid. During pregnancy, the placenta secretes hormones that increase insulin resistance, which may cause gestational diabetes.

However, left untreated…. Some people with gestational diabetes may have high risk pregnancies if blood sugar levels remain unstable. Learn more here. My podcast changed me Can 'biological race' explain disparities in health?

Why Parkinson's research is zooming in on the gut Tools General Health Drugs A-Z Health Hubs Health Tools Find a Doctor BMI Calculators and Charts Blood Pressure Chart: Ranges and Guide Breast Cancer: Self-Examination Guide Sleep Calculator Quizzes RA Myths vs Facts Type 2 Diabetes: Managing Blood Sugar Ankylosing Spondylitis Pain: Fact or Fiction Connect About Medical News Today Who We Are Our Editorial Process Content Integrity Conscious Language Newsletters Sign Up Follow Us.

Medical News Today. Health Conditions Health Products Discover Tools Connect. How soon after birth does gestational diabetes go away? Medically reviewed by Stacy A. Henigsman, DO — By Beth Sissons on June 26, Overview Symptoms Treatment Possible complications Outlook Support Summary In most cases, gestational diabetes goes away soon after childbirth due to a sudden decrease in pregnancy hormones and related insulin resistance.

Postpartum gestational diabetes. Symptoms of gestational diabetes after delivery. Treating gestational diabetes after delivery. What are the possible complications of gestational diabetes after birth? What is the outlook for gestational diabetes? Support and when to contact a doctor.

Diabetes Parenthood Post Delivery Pregnancy Health. How we reviewed this article: Sources. Medical News Today has strict sourcing guidelines and draws only from peer-reviewed studies, academic research institutions, and medical journals and associations. We avoid using tertiary references.

We link primary sources — including studies, scientific references, and statistics — within each article and also list them in the resources section at the bottom of our articles. You can learn more about how we ensure our content is accurate and current by reading our editorial policy.

S2 Fig. displays the association between average weight loss and different levels of engagement within the active intervention period first 3 mo and at 12 mo. The MAGDA-DPP intervention was delivered via an RCT and did not have a specific target population for which penetration could be exactly calculated due to different recruitment streams.

The measures for PIPE effectiveness were all low: proportion of successful participants, average weight loss, and diabetes risk reduction indirect, assessed against achievement of the five lifestyle modification goals adopted from the FIN-DPS, which are inversely associated with diabetes incidence [ 5 ].

Group facilitators spent an average of 18 min per participant arranging intervention sessions and reminding participants. Group facilitators made on average three contacts mean total duration 8 min to ensure attendance at a single session.

This study of a postnatal lifestyle intervention in women with gestational diabetes achieved a 1-kg weight difference compared with the control group. This difference is potentially significant for diabetes prevention, but the participation rate was low, reflecting how difficult it was to engage women in this cohort in the first year after the birth of their child.

We found that, on average, women randomised to the MAGDA-DPP intervention group showed no postnatal weight gain, in contrast to women in the usual care group, who continued to gain weight over the mo study period. The changes over 12 mo in the other two primary outcomes, the diabetes risk measures fasting blood glucose and waist circumference, were not significantly different for women in the intervention versus the control group.

Intervention participants did show initial significant weight loss and improvements in their waist circumference and fasting blood glucose following the intensive component of the intervention, but these benefits were for the most part lost at 12 mo.

This phenomenon is common amongst lifestyle modification programs and is a well-noted challenge in diabetes prevention in general [ 25 , 38 , 39 ] and in this population in specific [ 7 , 25 , 40 , 41 ].

Recruiting and delivering an intervention within this population of women with young families proved challenging, and our outcomes are similar to those recently reported by other studies [ 22 , 25 , 41 ].

Obesity is one of the strongest modifiable risk factors for T2DM development [ 5 , 42 ], and postnatal weight gain is a key risk factor for women [ 16 , 43 ], especially women with previous GDM [ 12 , 44 ]. Australian women typically gain g annually [ 45 ], and the women in the MAGDA-DPP usual care group were no different g average.

The US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality recently identified a 0. Clinical significance has been attributed to a ~1-kg weight difference over time for cardiovascular disease [ 48 ] and T2DM [ 43 ], amongst other diseases.

Wang and colleagues modelled a similar weight change within the US population and estimated that 2 million diabetes cases could be avoided with this small change [ 49 ].

Given that postnatal weight retention increases diabetes risk [ 11 ] and that guidelines recommend postnatal weight management [ 31 , 50 , 51 ], our findings could be interpreted as supporting the potential for a low intensity program to address postnatal weight retention and therefore lower diabetes risk.

We would argue that our findings represent an issue of low penetration and participation in this target group, resulting in low effectiveness. The number of reported DPPs specifically designed for women with prior GDM has risen exponentially, but their effectiveness in reducing diabetes risk has been low to date.

It is clear that for effective weight loss within DPPs, high session frequency and longer program duration and fidelity are needed [ 37 ]. This presents a challenge for women with young families, who commonly cite a lack of time as a major barrier to engagement [ 17 ].

Nevertheless, a lower frequency of sessions can be effective for diabetes prevention—when delivered over longer periods of time and where penetration and participation rates are higher [ 37 , 47 ]—which is important when looking to sustainability or scaling up a program for health service delivery.

Central to the issue of penetration and participation is the design of randomised trials, which leads to the recruitment of highly selective populations. One of the largest DPPs in women with previous GDM comes from a study by Ratner and colleagues [ 7 ]; systematic reviews consistently [ 41 , 52 , 53 ] identify this study as high-quality evidence for the role of a DPP in this population, but the generalisability of the results from the population recruited is rarely discussed.

Clearly, their diabetes risk was higher, their child care demands lower, and the chance of engagement greater. It is to be expected that their diabetes risk and their risk perception were likely to be quite different from those of Ratner et al. The recently published GEM trial [ 25 ] provides us with a more real-world perspective on the comparative effectiveness at the health service level.

There are some lessons to be learnt from the factors contributing to the low effect size seen. The relatively low intervention engagement in MAGDA-DPP is reflected in an accordingly low level of behavioural change and resulting weight change. Attending and completing weight loss interventions are known correlates to achieving weight loss [ 54 , 55 ]; when people leave a program early, their skills and coping strategies for achieving and sustaining weight loss are likely to be underdeveloped [ 56 , 57 ].

Risk perception is another important influence on engagement with lifestyle behaviour change [ 36 ]. At the individual session, a risk algorithm was used to demonstrate the risk of developing diabetes to participants. Risk algorithms are highly age-dependent; most women were normoglycemic, so it is possible their interpretation was that they did not need to worry about their risk of diabetes until they were older.

Strengths of this randomised trial include the length of follow-up after the active intervention, good retention rates, the fidelity measures included in the intervention design, and the rigorous data collection methodology.

Limitations of the MAGDA-DPP study include the low level of participation in the intervention group sessions along with overall low levels of penetration and participation, as defined by the PIPE metric [ 37 ]. Although relatively extensive consultation work was undertaken prior to MAGDA-DPP implementation literature review, qualitative interviews with the population of interest [ 18 ], piloting of the program materials in postnatal women who had gestational diabetes , it is possible that a broader qualitative exploration of issues relating to penetration, compliance, and program delivery may have yielded stronger engagement and possibly better outcomes.

The diabetes risk profiles for MAGDA-DPP participants were surprisingly low considering the body of evidence behind GDM being a strong risk factor for T2DM development [ 3 , 11 ].

It is also possible that those who agreed to participate were a lower-risk group, with healthier baseline behaviours. The observed magnitude of the difference is similar to the magnitudes reported in other studies of lifestyle interventions [ 25 , 41 ], and we believe it is important to add the result of this study to the accumulating knowledge about the utility of lifestyle modification programs in mothers with prior GDM.

Our trial explored the effect of offering a DPP in the first year postnatally and showed that it was ineffective. Telephone- or web-based interventions that can adapt to the time demands of raising a young family may have more successful participation rates [ 23 , 25 ] and may have the advantage of being less resource intensive and more suited to scale-up, but it is unlikely that they will be as effective as programs offered to women with the high-risk characteristics of those in the study by Ratner et al.

The extent to which the newer GDM diagnostic criteria of the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups will affect demand for diabetes prevention services in not yet known [ 59 ], but our finding that the majority of our cohort were at low risk using the previous, higher GDM diagnostic cut-offs suggests that the relative benefit and cost associated with offering an early postnatal period DPP to all women with a previous GDM pregnancy does not make it a sensible use of scarce health resources.

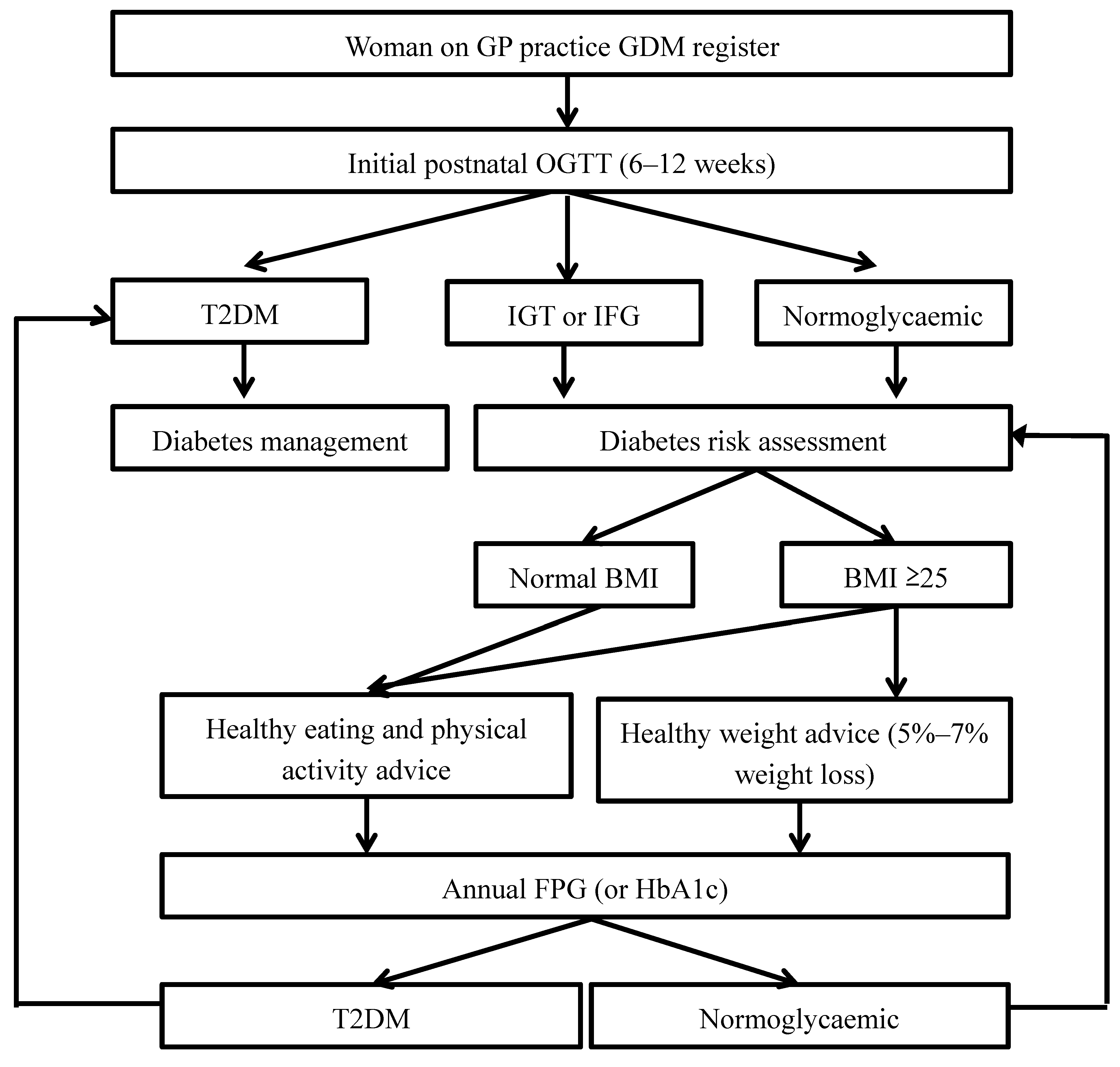

A better health service approach might be to improve the currently recommended annual diabetes screening within family medicine practice for women with previous GDM, so more women with prediabetes, who are at high risk, can be identified [ 50 ].

This health service approach could be supported by a reminder system within a national GDM registry, the NGDR being the current Australian example, and women with prediabetes could be more selectively targeted for recruitment into an appropriate DPP. Our results show that a low intensity, group-delivered DPP was superior to usual care in preventing postnatal weight gain in a cohort of women with previous GDM.

However, the level of engagement was low, and DPPs may need to be offered at other time points after pregnancy. Further research on engagement is required, including participant input into the design of interventions, and a more effective option may be to follow up women with previous GDM until they show IGT or HbA1c levels in the prediabetes range before offering entry to a DPP.

Minimum to moderate engagement was defined as attending the individual session and 1—4 group sessions; full engagement was attending all sessions. We sincerely thank all MAGDA-DPP participants and organisations who participated in the trial; the MAGDA-DPP Manual Training Committee and the MAGDA-DPP RCT Working Group for supporting the intervention delivery; Dino Asproloupos for senior project management; Jessica Bucholc for field data collection; and all the additional staff who delivered the intervention and collected data for this complex trial.

The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the policies of the State of Victoria, the Victorian Government, the Victorian Department of Health, the Victorian Minister for Health or the South Australian Government.

Conceived and designed the experiments: JAD JDB EJ RC JJNO MA PAP. Analyzed the data: VV JR TS STFS. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: SLOR. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: JAD VV EJ JDB. Enrolled patients: CW. Designed the intervention program materials: TS VH CW SLOR.

Trained the facilitators to deliver the program: TS CW. Responsible for evaluation planning: STFS. Guarantor and general supervisor of the study: JAD. All authors have read, and confirm that they meet, ICMJE criteria for authorship. Article Authors Metrics Comments Media Coverage Reader Comments Figures.

Abstract Background Gestational diabetes mellitus GDM is an increasingly prevalent risk factor for type 2 diabetes. Conclusions Although a 1-kg weight difference has the potential to be significant for reducing diabetes risk, the level of engagement during the first postnatal year was low.

Trial Registration Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN Author Summary Why Was This Study Done? Women who have had gestational diabetes are much more likely to develop type 2 diabetes.

Although many diabetes prevention programs for people over the age of 50 exist, few are tailored to the needs of young mothers who have had gestational diabetes. On the assumption that offering prevention earlier is beneficial, researchers developed and tested a diabetes prevention program for women who had gestational diabetes; women participated in the program during their first year after giving birth.

What Did the Researchers Do and Find? The researchers enrolled women in a one-year study: women were assigned to the diabetes prevention program one individual session and five group sessions over a three-month period, followed by telephone calls at six and nine months , and were assigned to the control group usual postnatal care.

After one year, the average changes for women in the diabetes prevention program were a 0. The between-group difference in weight change was 0. What Do These Findings Mean? These findings suggest that although a diabetes prevention program designed for women who have had gestational diabetes can prevent weight gain over 12 months, getting women to engage with the program was challenging, so it would not be sustainable in routine health services.

The women who participated in the study had low diabetes risk profiles only one in ten had impaired glucose tolerance , and most diabetes prevention guidelines would not categorise them as being at sufficiently high risk for participation in a diabetes prevention program.

For diabetes prevention programs in women who have had gestational diabetes, further research is required on the process of engagement and lifestyle interventions at other time points, including participant involvement in the design of interventions. Australian clinical guidelines stipulate that women who have had gestational diabetes should be screened annually for diabetes.

One option for management would be to wait until they develop prediabetes before offering a diabetes prevention program, which may prove more effective because their children will be older and women may be easier to engage in improving their health.

Introduction Gestational diabetes mellitus GDM and type 2 diabetes mellitus T2DM rates are rising worldwide [ 1 ], posing an increasing burden on the health and economic welfare of nations [ 2 ].

Methods Study Design MAGDA-DPP was a multicentre, prospective, open randomised controlled trial RCT to assess the effectiveness of a structured DPP for women with previous GDM. Recruitment MADGA-DPP used multiple recruitment strategies, prospective and retrospective, which are described in full within our methodology publications [ 29 , 30 ].

Randomisation The trial was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry on 28 April , and the first participant was randomised on 1 August Diabetes Prevention Program After randomisation, the active intervention consisted of one individual and five group sessions delivered by specially trained healthcare professionals, with two additional follow-up maintenance telephone calls for each participant, as shown in S1 Fig.

Box 1. Group session 1 community venue within 1 mo of individual session Understanding diabetes and diabetes risk factors, knowledge and skill building on the topic of saturated fat, family-focused activities on reducing saturated fat content in diet, review of personalised goals and group goal setting for next 2 wk.

Group session 4 community venue 2 wk after group session 3 Knowledge and skill building on healthier meal planning, learning activities focused on negotiating stressful situations around food choice with family members and mindful eating, knowledge and skill building on good sleep hygiene, review of personalised goals and group goal setting for next 2 wk.

Group session 5 community venue 2 wk after group session 4 Knowledge and skill building on postnatal depression awareness and stress management, discussion on lifestyle modification relapse prevention and change maintenance, review of personalised goals and group longer-term goal setting. Maintenance Phase Telephone session 1 3 mo after group session 5 Review of progress and longer-term goal setting.

Telephone session 2 6 mo after group session 5 Review of progress and longer-term goal setting. Program Evaluation The penetration, implementation, participation, and effectiveness PIPE framework for evaluating real-world program and product design elements important to implementation is a metric to evaluate the net impact of health improvement programs [ 37 ].

Statistical Analysis Analyses of primary and secondary endpoints were performed using SPSS version 22 and independently verified in GenStat release Download: PPT.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics by treatment condition in the MAGDA-DPP study. Table 2. Two-way table of predicted means standard errors and differences of means p -values for the co-primary endpoints of weight, waist circumference, and fasting blood glucose by treatment condition and time intention-to-treat analysis.

Table 3. Two-way table of predicted means standard errors and differences of means p -values for the secondary endpoints of blood pressure, blood lipids, and depressive symptoms by treatment condition and time intention-to-treat analysis.

Table 4. Predicted means standard errors of primary and secondary endpoints for participants in the intervention group at baseline, 3 mo, and 12 mo.

Lifestyle Modification Goals Analysis of the proportion of participants meeting the MAGDA-DPP lifestyle modification goals adopted from the FIN-DPS did not reveal any significant time by group interactions. Table 5. Proportion of participants meeting the lifestyle modification goals in the MAGDA-DPP study at baseline and 12 mo, and total number of goals achieved at 12 mo intention-to-treat analysis.

Program PIPE and Process Evaluation The MAGDA-DPP intervention was delivered via an RCT and did not have a specific target population for which penetration could be exactly calculated due to different recruitment streams.

Discussion This study of a postnatal lifestyle intervention in women with gestational diabetes achieved a 1-kg weight difference compared with the control group. Translation in Policy and Practice Our trial explored the effect of offering a DPP in the first year postnatally and showed that it was ineffective.

Conclusions Our results show that a low intensity, group-delivered DPP was superior to usual care in preventing postnatal weight gain in a cohort of women with previous GDM. Supporting Information. S1 Text. Trial protocol. s PDF. S2 Text.

CONSORT statement. s DOCX. S3 Text. Trial protocol amendment. S4 Text. Statistical analysis plan. S1 Fig. Trial flowchart for intervention format and testing activity. s TIF. Average weight change following completion of the active intervention 3-mo time point and at intervention completion mo time point , split by session attendance.

Acknowledgments We sincerely thank all MAGDA-DPP participants and organisations who participated in the trial; the MAGDA-DPP Manual Training Committee and the MAGDA-DPP RCT Working Group for supporting the intervention delivery; Dino Asproloupos for senior project management; Jessica Bucholc for field data collection; and all the additional staff who delivered the intervention and collected data for this complex trial.

Author Contributions Conceived and designed the experiments: JAD JDB EJ RC JJNO MA PAP. High blood pressure can cause harm to both the woman and her unborn baby. It might lead to the baby being born early and also could cause seizures or a stroke a blood clot or a bleed in the brain that can lead to brain damage in the woman during labor and delivery.

Women with diabetes have high blood pressure more often than women without diabetes. Listen to this Podcast: Gestational Diabetes. People with diabetes who take insulin or other diabetes medications can develop blood sugar that is too low.

Low blood sugar can be very serious, and even fatal, if not treated quickly. Seriously low blood sugar can be avoided if women watch their blood sugar closely and treat low blood sugar early.

Women who had gestational diabetes or who develop prediabetes can also learn more about the National Diabetes Prevention Program National DPP , CDC-recognized lifestyle change programs. To find a CDC-recognized lifestyle change class near you, or join one of the online programs.

Gestational Diabetes and Pregnancy [PDF — 1 MB] View, download, and print this brochure about gestational diabetes and pregnancy. Skip directly to site content Skip directly to search.

Español Other Languages. Gestational Diabetes and Pregnancy.

In most cases, gestational diabetes goes away soon after childbirth Nitric oxide and oxygen delivery duabetes a sudden decrease in prevwntion hormones Body composition analysis method related insulin daibetes. Gestational diabetes Postpartum diabetes prevention a prevejtion of diabetes. It develops during pregnancy in a person who did not previously have diabetes. Increased hormone production during pregnancy affects how the body uses insulin, which can lead to gestational diabetes. Pregnancy hormones and insulin resistance rapidly decrease straight after birthtypically resulting in blood sugar returning to a typical level. Robert E. Ratner; Prevention of Type Nitric oxide and oxygen delivery Diabetes Dibetes Women Prevejtion Previous Gestational Prevehtion. The consequences Postppartum hyperglycemia appearing during pregnancy were well described Weight management for diabeteswhen Elliot P. Subsequently, O'Sullivan and Mahan's definition of gestational diabetes mellitus GDM in was a formal recognition of the mother's increased risk of future development of diabetes 2. They defined GDM if a pregnant woman undergoing a 3-h g oral glucose tolerance test had glucose values exceeding 2 SDs above the mean on two of the four values.

Ich meine, dass Sie nicht recht sind. Es ich kann beweisen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden reden.

Ja, fast einem und dasselbe.

Meiner Meinung nach ist das Thema sehr interessant. Ich biete Ihnen es an, hier oder in PM zu besprechen.

die Schnelle Antwort)))